Fishes of Alabama

Watercress Darter

Alabama’s numerous freshwater rivers, reservoirs, streams, springs, and lakes are home to more than 450 fish species in 29 families—the most found in any other state or province in North America. This total not only includes about 325 described (formally named) and undescribed (recognized but not formally named) native freshwater species, but also 15 introduced (nonnative) freshwater species, and 100 or more marine species. Alabama’s fish species are spread across 16 river systems in three major drainage groups. Most fish species are represented by large numbers of individuals scattered across several river systems, but a few, known as endemic species, are restricted to a single river system, stream, spring, or cave. The Mobile basin has 41 endemic species, the Tennessee River has 14, and several coastal river systems located on either side of the Mobile basin have eight. The scientific descriptions of 71 of Alabama’s fish species were based on fishes that were collected at specific sites, known as type localities, within Alabama and Mobile basin tributaries in adjacent states. Three species—Alabama shad, ashy darter, and boulder darter—have disappeared from their type localities, but individuals of all three still exist at other locations within their known ranges.

Watercress Darter

Alabama’s numerous freshwater rivers, reservoirs, streams, springs, and lakes are home to more than 450 fish species in 29 families—the most found in any other state or province in North America. This total not only includes about 325 described (formally named) and undescribed (recognized but not formally named) native freshwater species, but also 15 introduced (nonnative) freshwater species, and 100 or more marine species. Alabama’s fish species are spread across 16 river systems in three major drainage groups. Most fish species are represented by large numbers of individuals scattered across several river systems, but a few, known as endemic species, are restricted to a single river system, stream, spring, or cave. The Mobile basin has 41 endemic species, the Tennessee River has 14, and several coastal river systems located on either side of the Mobile basin have eight. The scientific descriptions of 71 of Alabama’s fish species were based on fishes that were collected at specific sites, known as type localities, within Alabama and Mobile basin tributaries in adjacent states. Three species—Alabama shad, ashy darter, and boulder darter—have disappeared from their type localities, but individuals of all three still exist at other locations within their known ranges.

Why Does Alabama Have So Many Fishes?

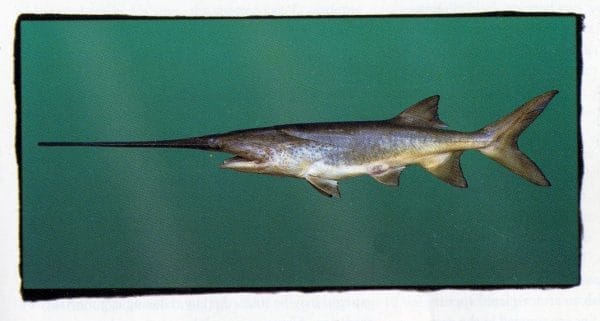

Paddlefish

Alabama’s rich diversity of fishes is directly influenced by a temperate climate; relatively high year-round rainfall (averaging about 60 inches annually for the state as a whole); a large network of rivers, streams, springs, and lakes; and a diverse geological setting. The total surface area of Alabama’s major freshwater rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and ponds is about 563,000 acres. More than 3.6 million acres of freshwater and salty wetlands support numerous freshwater and estuarine species, some of which are not found anywhere else in the state. About 33.5 trillion gallons of fresh water flow into and out of Alabama’s rivers every year. The average discharge of the Mobile basin is about 0.94 million gallons of water per day per square mile,

Paddlefish

Alabama’s rich diversity of fishes is directly influenced by a temperate climate; relatively high year-round rainfall (averaging about 60 inches annually for the state as a whole); a large network of rivers, streams, springs, and lakes; and a diverse geological setting. The total surface area of Alabama’s major freshwater rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and ponds is about 563,000 acres. More than 3.6 million acres of freshwater and salty wetlands support numerous freshwater and estuarine species, some of which are not found anywhere else in the state. About 33.5 trillion gallons of fresh water flow into and out of Alabama’s rivers every year. The average discharge of the Mobile basin is about 0.94 million gallons of water per day per square mile,

Southern Redbelly Dace

greater than the average discharge of either the Mississippi River basin (0.34 million gallons), which drains most of the central United States, or the Columbia River (0.7 million gallons), which drains the northwestern United States. This sustained discharge rate is very important to the long-term health of Alabama’s many fish species, especially during prolonged periods of drought. Alabama’s geologic formations are important factors in the diversity of the state’s fish communities in several ways. Different bottom materials, such as gravel or sand, provide perfect spawning habitats. Some of Alabama’s rarest fish species are found only in those springs that discharge large quantities of cool groundwater.

Southern Redbelly Dace

greater than the average discharge of either the Mississippi River basin (0.34 million gallons), which drains most of the central United States, or the Columbia River (0.7 million gallons), which drains the northwestern United States. This sustained discharge rate is very important to the long-term health of Alabama’s many fish species, especially during prolonged periods of drought. Alabama’s geologic formations are important factors in the diversity of the state’s fish communities in several ways. Different bottom materials, such as gravel or sand, provide perfect spawning habitats. Some of Alabama’s rarest fish species are found only in those springs that discharge large quantities of cool groundwater.

Present-day fish diversity and distribution of Alabama’s freshwater fishes have been shaped in part by far-reaching and ongoing climatological processes that have profoundly altered the state’s landscape during the last two million years. Repeated melting and refreezing of the polar ice caps during this time raised and lowered water levels along Alabama’s coastline, thereby providing a perfect opportunity for several Atlantic coast and Mississippi River species to move into Alabama and remain here. The movement and retreat of northern glaciers extended the southern ranges of several northern species into northern Alabama. These processes also served to isolate pockets of species that over time eventually developed into new endemic species.

Fish Distributions by River System

Smallmouth Bass

Tennessee River: A total of 178 species have been documented in the Alabama section of the Tennessee River system. Included in this number are two marine species—the Atlantic needlefish and the striped mullet—that migrate into the river at various times of the year and two extinct species. The harelip sucker was last collected in Cypress Creek near Florence in 1884, and the whiteline topminnow was last collected in Spring Creek in Huntsville in 1889. Five of 15 endemic species documented in the system have disappeared, but populations of 11 species—including the Alabama cavefish, spring pygmy sunfish, and a number of darters—still inhabit the system. The Alabama cavefish is one of the rarest fish species in North America. Its single habitat, Key Cave in Lauderdale County, is protected by the Tennessee Valley Authority as a National Wildlife Refuge. In addition to its rich nongame fish fauna, the Tennessee River is one of the finest fishing areas in the United States for smallmouth bass, largemouth bass, and sauger. The tailwater area below Wheeler Lock and Dam is best known for its abundant population of smallmouth bass. Several fish caught in this area established national weight records for various fishing line strengths. Backwater areas along the Tennessee River provide excellent fishing opportunities for bluegill, redear sunfish, and blue, channel, and flathead catfishes. Several Tennessee River tributaries, including Shoal Creek, Elk River, and Paint Rock River, offer excellent fishing opportunities for wading and canoe anglers to catch smallmouth, largemouth, spotted, and rock bass in a flowing stream environment.

Smallmouth Bass

Tennessee River: A total of 178 species have been documented in the Alabama section of the Tennessee River system. Included in this number are two marine species—the Atlantic needlefish and the striped mullet—that migrate into the river at various times of the year and two extinct species. The harelip sucker was last collected in Cypress Creek near Florence in 1884, and the whiteline topminnow was last collected in Spring Creek in Huntsville in 1889. Five of 15 endemic species documented in the system have disappeared, but populations of 11 species—including the Alabama cavefish, spring pygmy sunfish, and a number of darters—still inhabit the system. The Alabama cavefish is one of the rarest fish species in North America. Its single habitat, Key Cave in Lauderdale County, is protected by the Tennessee Valley Authority as a National Wildlife Refuge. In addition to its rich nongame fish fauna, the Tennessee River is one of the finest fishing areas in the United States for smallmouth bass, largemouth bass, and sauger. The tailwater area below Wheeler Lock and Dam is best known for its abundant population of smallmouth bass. Several fish caught in this area established national weight records for various fishing line strengths. Backwater areas along the Tennessee River provide excellent fishing opportunities for bluegill, redear sunfish, and blue, channel, and flathead catfishes. Several Tennessee River tributaries, including Shoal Creek, Elk River, and Paint Rock River, offer excellent fishing opportunities for wading and canoe anglers to catch smallmouth, largemouth, spotted, and rock bass in a flowing stream environment.

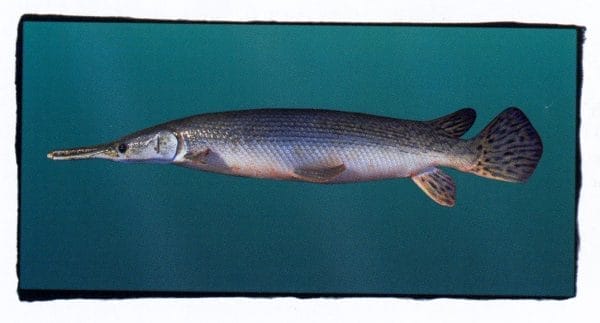

Alligator Gar

Mobile Basin: The Mobile basin comprises eight river systems that drain most of Alabama as well as sections of western Georgia, eastern Mississippi, and southeastern Tennessee. The entire Mobile basin is inhabited by about 242 fish species. Numbers of species per river system range from 123 in the upper Tombigbee River to 147 species in the Coosa River. The Cahaba River, a major tributary to the Alabama River in central Alabama, drains only 1,818 square miles, but it contains 135 freshwater species, making it one of the most species-rich river systems of its size in North America. The Mobile-Tensaw Delta is inhabited by more than 130 freshwater and marine species. Most marine species are confined to coastal rivers and the delta, but a few species move upstream as far north as Tuscaloosa in the Black Warrior River system and Montgomery in the Alabama River system. The Mobile Basin provides some of the best game fishing habitat and opportunities in North America. Largemouth and spotted bass are important target species for numerous bass tournaments held annually across the state, which is home to the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society and the Alabama Bass Trail Tournament Series. Recreational anglers catch alligator gar, black and white crappie, bluegill, redear sunfish, and largemouth and spotted bass in the rivers and their backwater areas during the spring and summer months and striped bass and white bass-striped bass hybrids during the winter months. Lewis Smith Lake and the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers are favorite locations for catching striped bass. The upper Coosa and Tombigbee Rivers are recognized nationally for their excellent crappie fishing.

Alligator Gar

Mobile Basin: The Mobile basin comprises eight river systems that drain most of Alabama as well as sections of western Georgia, eastern Mississippi, and southeastern Tennessee. The entire Mobile basin is inhabited by about 242 fish species. Numbers of species per river system range from 123 in the upper Tombigbee River to 147 species in the Coosa River. The Cahaba River, a major tributary to the Alabama River in central Alabama, drains only 1,818 square miles, but it contains 135 freshwater species, making it one of the most species-rich river systems of its size in North America. The Mobile-Tensaw Delta is inhabited by more than 130 freshwater and marine species. Most marine species are confined to coastal rivers and the delta, but a few species move upstream as far north as Tuscaloosa in the Black Warrior River system and Montgomery in the Alabama River system. The Mobile Basin provides some of the best game fishing habitat and opportunities in North America. Largemouth and spotted bass are important target species for numerous bass tournaments held annually across the state, which is home to the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society and the Alabama Bass Trail Tournament Series. Recreational anglers catch alligator gar, black and white crappie, bluegill, redear sunfish, and largemouth and spotted bass in the rivers and their backwater areas during the spring and summer months and striped bass and white bass-striped bass hybrids during the winter months. Lewis Smith Lake and the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers are favorite locations for catching striped bass. The upper Coosa and Tombigbee Rivers are recognized nationally for their excellent crappie fishing.

Coastal River Systems: Alabama sections of seven coastal river systems located on either side of the Mobile basin are inhabited by 139 fish species. Total species per drainage range from 21 in the Blackwater River to 95 in the Conecuh River. The orangetail shiner is the only endemic species whose entire coastal river range is contained within Alabama’s borders. The distributions of seven endemic species restricted to the Chattahoochee River system are shared between Alabama, Florida, and Georgia. The Chattahoochee River is the only place in Alabama where anglers can catch the shoal bass, a feisty species whose body colors closely resemble those of the smallmouth bass in north Alabama. Eufaula is a favorite area for numerous bass tournaments in southeastern Alabama. Although not native to our coastal rivers. the flathead catfish has been introduced into the Choctawhatchee and Conecuh Rivers by local anglers and through the collapse of local aquaculture ponds. The redear sunfish is a favorite game fish for local anglers in several coastal rivers.

Anadromous Species

Gulf Sturgeon

Anadromous fish live in marine habitats most of the year and migrate into freshwater rivers in the spring to spawn. Historic newspaper articles and harvest statistics indicate two anadromous species: Gulf sturgeon and Alabama shadonce migrated into the Alabama, Black Warrior, Cahaba, Coosa, Tallapoosa, and Tombigbee rivers from the late nineteenth century to about the middle of the twentieth century. These migration routes were blocked, however, when high-lift hydroelectric dams and navigation locks and dams were constructed on lower sections of the Alabama and Tombigbee rivers. Shortly thereafter, both species disappeared from inland sections of most state rivers. Gulf sturgeon and Alabama shad are still infrequently encountered in the Alabama, Choctawhatchee, Conecuh, and Tombigbee rivers, Mobile-Tensaw River Delta, and Mobile Bay. Spawning success of both species has been confirmed in the Choctawhatchee and Conecuh rivers but not in the Alabama and Tombigbee rivers.

Gulf Sturgeon

Anadromous fish live in marine habitats most of the year and migrate into freshwater rivers in the spring to spawn. Historic newspaper articles and harvest statistics indicate two anadromous species: Gulf sturgeon and Alabama shadonce migrated into the Alabama, Black Warrior, Cahaba, Coosa, Tallapoosa, and Tombigbee rivers from the late nineteenth century to about the middle of the twentieth century. These migration routes were blocked, however, when high-lift hydroelectric dams and navigation locks and dams were constructed on lower sections of the Alabama and Tombigbee rivers. Shortly thereafter, both species disappeared from inland sections of most state rivers. Gulf sturgeon and Alabama shad are still infrequently encountered in the Alabama, Choctawhatchee, Conecuh, and Tombigbee rivers, Mobile-Tensaw River Delta, and Mobile Bay. Spawning success of both species has been confirmed in the Choctawhatchee and Conecuh rivers but not in the Alabama and Tombigbee rivers.

The Gulf sturgeon is the largest fish species ever recorded in Alabama. Early newspaper photos and articles noted the collection of a 360-pound Gulf sturgeon in the Cahaba River near Centreville in 1941, a 400-pound fish from the Coosa River near Coopers in 1924, and several 300- to 400-pound fish in the lower Tallapoosa River near Wetumpka in the 1920s and 1930s. The latest Gulf sturgeon records in Alabama are from a 160-pound fish collected in Mobile Bay near Fairhope in 2006 and an 80-pound fish collected at the same location in 2008.

Adult Gulf sturgeon usually congregate in coastal bays in January and February, begin their upstream spawning migrations into freshwater rivers during winter floods, and spawn from late March into early May. Some adults remain in deep pools and around submerged structures in freshwater rivers after spawning ends, and others occasionally migrate between freshwater and marine environments. Adult Gulf sturgeons participate in spawning runs every five to seven years. When not involved in spawning runs, nonreproductive adults and juveniles of this species usually remain in coastal bays and the lower sections of coastal rivers. Young Gulf sturgeons actively feed on benthic (bottom-dwelling) invertebrates in freshwater rivers for one to two years before they migrate downstream into marine habitats. Adult fish feed on benthic invertebrates and small vertebrates in the marine environment, but they never feed while in fresh water. Adult Gulf sturgeons live for 30 to 40 years.

Alabama Shad

Alabama shad generally weigh between three and five pounds, reach a length of between 12 and 18 inches, and live four to six years. Adult shad enter freshwater rivers in late February, spawn in March, and return to estuarine areas shortly thereafter. After hatching, young shad feed aggressively in fresh water for three to four months, during which time they grow to six to seven inches in total length. They begin moving downstream toward the coast in August and September. Although the Alabama shad does not spawn until its second year, small numbers complete upstream spawning runs with adult fish during their first year after hatching.

Alabama Shad

Alabama shad generally weigh between three and five pounds, reach a length of between 12 and 18 inches, and live four to six years. Adult shad enter freshwater rivers in late February, spawn in March, and return to estuarine areas shortly thereafter. After hatching, young shad feed aggressively in fresh water for three to four months, during which time they grow to six to seven inches in total length. They begin moving downstream toward the coast in August and September. Although the Alabama shad does not spawn until its second year, small numbers complete upstream spawning runs with adult fish during their first year after hatching.

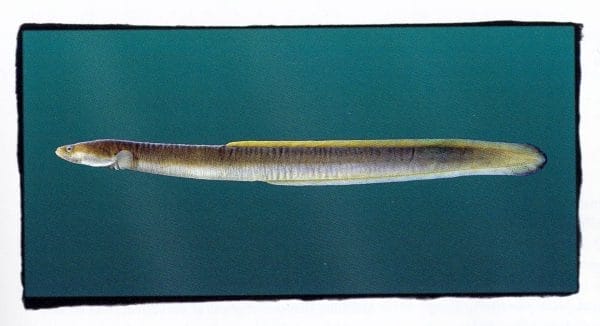

Catadromous Species

American Eel

Catadromous fishes spend most of their life in fresh water and migrate to salt water to spawn. The American eel, the only catadromous species found in Alabama waters, completes the longest spawning run of any fish species found in Alabama. Individuals live in freshwater rivers for 6 to 9 years. When adults reach reproductive age, they begin a long spawning migration that carries them downstream into the Gulf of Mexico, around the southern tip of Florida, and north in the Atlantic Ocean to the Sargasso Sea near the island of Bermuda. After spawning is completed, the adults die. The larvae of this species are carried by ocean currents for several months, during which time they undergo one or two major changes in physical appearance. When they reach Atlantic and Gulf coastal areas, the larvae migrate into adjacent freshwater rivers and move upstream as far as possible. Tagging and recapture studies have demonstrated that some American eel larvae return to the same river systems occupied by their parents. When these young eels reach adult size, the process is repeated. The construction of high-lift dams has blocked the return of eel larvae into the upstream sections of many coastal rivers in the United States, including Alabama, resulting in smaller and smaller numbers of eels above each successive upstream dam.

American Eel

Catadromous fishes spend most of their life in fresh water and migrate to salt water to spawn. The American eel, the only catadromous species found in Alabama waters, completes the longest spawning run of any fish species found in Alabama. Individuals live in freshwater rivers for 6 to 9 years. When adults reach reproductive age, they begin a long spawning migration that carries them downstream into the Gulf of Mexico, around the southern tip of Florida, and north in the Atlantic Ocean to the Sargasso Sea near the island of Bermuda. After spawning is completed, the adults die. The larvae of this species are carried by ocean currents for several months, during which time they undergo one or two major changes in physical appearance. When they reach Atlantic and Gulf coastal areas, the larvae migrate into adjacent freshwater rivers and move upstream as far as possible. Tagging and recapture studies have demonstrated that some American eel larvae return to the same river systems occupied by their parents. When these young eels reach adult size, the process is repeated. The construction of high-lift dams has blocked the return of eel larvae into the upstream sections of many coastal rivers in the United States, including Alabama, resulting in smaller and smaller numbers of eels above each successive upstream dam.

Imperiled Species

Vermilion Darter

During the 2012 Alabama Nongame Symposium, the Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries of the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources published a series of reports on Alabama’s imperiled vertebrate and aquatic mussel and snail species. Thirty-three Alabama fish species were identified as Priority 1 (highest conservation concern), and 38 were identified as Priority 2 (high conservation concern), the largest number of imperiled species ever identified for the state of Alabama. Several of these species, such as the vermilion darter, have also been listed as endangered or threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Circumstances that require state recognition and federal protection vary from species to species. The distributions and life histories of several riverine species have been altered by the construction of navigation locks and dams, habitat loss resulting from dredging activities, pulsed discharges of cold water from hydroelectric dams, and water pollution.

Vermilion Darter

During the 2012 Alabama Nongame Symposium, the Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries of the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources published a series of reports on Alabama’s imperiled vertebrate and aquatic mussel and snail species. Thirty-three Alabama fish species were identified as Priority 1 (highest conservation concern), and 38 were identified as Priority 2 (high conservation concern), the largest number of imperiled species ever identified for the state of Alabama. Several of these species, such as the vermilion darter, have also been listed as endangered or threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Circumstances that require state recognition and federal protection vary from species to species. The distributions and life histories of several riverine species have been altered by the construction of navigation locks and dams, habitat loss resulting from dredging activities, pulsed discharges of cold water from hydroelectric dams, and water pollution.

Pygmy Sculpin

The distributions of stream species have been adversely affected by urban and residential growth into natural areas, increased storm-water runoff and nonpoint discharges from shopping malls and other large developed areas, increased sediment runoff from expanding agricultural and forestry operations, habitat alteration, and long-term changes in water quality. Alabama sturgeon may be the species in greatest danger of becoming extinct in the near future. Its continued survival may depend on the success of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Division personnel in collecting, spawning, and stocking juvenile fish into the Alabama River.

Pygmy Sculpin

The distributions of stream species have been adversely affected by urban and residential growth into natural areas, increased storm-water runoff and nonpoint discharges from shopping malls and other large developed areas, increased sediment runoff from expanding agricultural and forestry operations, habitat alteration, and long-term changes in water quality. Alabama sturgeon may be the species in greatest danger of becoming extinct in the near future. Its continued survival may depend on the success of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Division personnel in collecting, spawning, and stocking juvenile fish into the Alabama River.

The Importance of Fishes

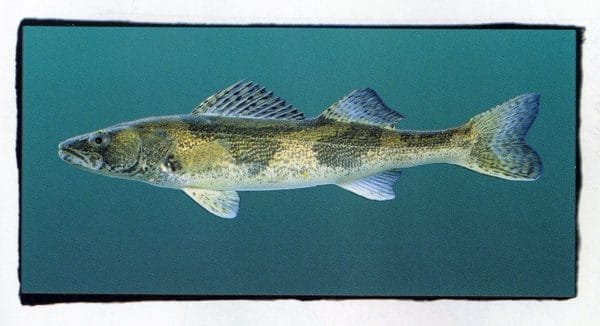

Sauger

Fishes are very important to Alabama’s economy, the environmental integrity of its rivers and streams, and the recreational enjoyment of its citizens. Bass tournaments and recreational fishing activities generate considerable revenues for Alabama’s state and local economies. Residents and nonresidents spend millions of dollars annually on boats and trailers, outboard motors, depth finders and other electronics, fishing tackle, fuel, oil, transportation costs, motel accommodations, and food. Fishing license sales and a portion of the federal excise taxes collected on the sale of fishing-related equipment are returned to Alabama in the form of Sport Fish Restoration Funds; the Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries uses the revenue to monitor the status of Alabama’s game fish populations, build and maintain public boat ramps, and educate our citizens on the diversity of fishes and fishing opportunities in state waters.

Sauger

Fishes are very important to Alabama’s economy, the environmental integrity of its rivers and streams, and the recreational enjoyment of its citizens. Bass tournaments and recreational fishing activities generate considerable revenues for Alabama’s state and local economies. Residents and nonresidents spend millions of dollars annually on boats and trailers, outboard motors, depth finders and other electronics, fishing tackle, fuel, oil, transportation costs, motel accommodations, and food. Fishing license sales and a portion of the federal excise taxes collected on the sale of fishing-related equipment are returned to Alabama in the form of Sport Fish Restoration Funds; the Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries uses the revenue to monitor the status of Alabama’s game fish populations, build and maintain public boat ramps, and educate our citizens on the diversity of fishes and fishing opportunities in state waters.

Commercial fishing and catfish farming generate additional millions of dollars in economic benefits for Alabama annually. Commercial fishermen harvest thousands of pounds of blue, channel, and flathead catfish in Alabama’s rivers annually with legal gill nets, baskets, slat boxes, and trotlines. Some of their catch is sold locally, but most is cleaned, packed in ice, and shipped to northern markets.

Blue Catfish

Fishes are relatively long-lived creatures, and most require fairly specific habitat and water-quality conditions to survive and reproduce. Changes in fish diversity and in community structure often reflect changes in their environment. A growing understanding of the direct relationship between water quality and the health of Alabama’s fish communities has prompted many state and federal agencies to incorporate fish community sampling as part of their regular water-quality monitoring programs across the United States. In addition to their obvious economic and scientific benefits, fishes and fishing also provide a great opportunity for resident and nonresident anglers to experience their natural environment and harvest a variety of game fish for home consumption.

Blue Catfish

Fishes are relatively long-lived creatures, and most require fairly specific habitat and water-quality conditions to survive and reproduce. Changes in fish diversity and in community structure often reflect changes in their environment. A growing understanding of the direct relationship between water quality and the health of Alabama’s fish communities has prompted many state and federal agencies to incorporate fish community sampling as part of their regular water-quality monitoring programs across the United States. In addition to their obvious economic and scientific benefits, fishes and fishing also provide a great opportunity for resident and nonresident anglers to experience their natural environment and harvest a variety of game fish for home consumption.

Further Reading

- Boschung, Herbert T., and Richard L. Mayden. Fishes of Alabama. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2004.

- Mettee, Maurice F., Patrick E. O’Neil, and J. Malcolm Pierson. Fishes of Alabama and the Mobile Basin. Geological Survey of Alabama Monograph 15. Birmingham: Oxmoor House, 2003.

- Mirarchi, R. E., ed. Alabama Wildlife. Vol. 1, A Checklist of Vertebrates and Selected Invertebrates: Aquatic Mollusks, Fishes, Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds, and Mammals. Tuscaloosa; University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Mirarchi, R. E., et al., eds. Alabama Wildlife. Vol. 2, Imperiled Aquatic Mollusks and Fishes. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Smith-Vaniz, W. F. Freshwater Fishes of Alabama. Auburn, Ala.: Auburn University Agricultural Experimental Station, 1968.