University of West Alabama

University of West Alabama

For more than 170 years, the University of West Alabama (UWA) has served not only as a center for teacher training and higher education, but also as a gathering place for community and cultural events, including symphonic performances, dramatic productions, and outdoor activities. Tracing its beginning to the charter of Livingston Female Academy in 1835, UWA is one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in the state. The university is located in Livingston in Sumter County, just 20 miles from the Mississippi state line and 57 miles from Tuscaloosa, in Alabama‘s Black Belt region. In 2021, UWA became the host site for the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame, after the closure of Judson College.

University of West Alabama

For more than 170 years, the University of West Alabama (UWA) has served not only as a center for teacher training and higher education, but also as a gathering place for community and cultural events, including symphonic performances, dramatic productions, and outdoor activities. Tracing its beginning to the charter of Livingston Female Academy in 1835, UWA is one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in the state. The university is located in Livingston in Sumter County, just 20 miles from the Mississippi state line and 57 miles from Tuscaloosa, in Alabama‘s Black Belt region. In 2021, UWA became the host site for the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame, after the closure of Judson College.

Jones Hall

Livingston Female Academy was established by Scots-Irish Presbyterians who constituted the majority of seats on the original board of trustees selected in 1836. The purpose of the school was to educate future teachers, while also offering course work in art, music, languages, and home economics. Tuition at this time was $20 annually, with an additional $25 charged for piano lessons and $10 for French and embroidery. Jones Hall was the first building constructed on the campus, in 1837, and was located near what is now Brock Hall. (Named for Capt. W. A. C. Jones, an original board member, the building was lost to fire in the 1890s.) On January 15, 1840, state lawmakers incorporated Livingston Female Academy, granted it tax-exempt status, and gave the board the authority to establish rules and regulations.

Jones Hall

Livingston Female Academy was established by Scots-Irish Presbyterians who constituted the majority of seats on the original board of trustees selected in 1836. The purpose of the school was to educate future teachers, while also offering course work in art, music, languages, and home economics. Tuition at this time was $20 annually, with an additional $25 charged for piano lessons and $10 for French and embroidery. Jones Hall was the first building constructed on the campus, in 1837, and was located near what is now Brock Hall. (Named for Capt. W. A. C. Jones, an original board member, the building was lost to fire in the 1890s.) On January 15, 1840, state lawmakers incorporated Livingston Female Academy, granted it tax-exempt status, and gave the board the authority to establish rules and regulations.

Livingston Female Academy awarded its first diploma in 1843 to Elizabeth Houston, the daughter of M. L. Houston, a prominent local businessman and a school trustee. The first principal of the school was A. A. Kimbrell, followed by Margaret McShan. In 1853, Robert Dickens Webb arrived in Sumter County and served as a trustee for more than 40 years. He led the school during the Civil War and Reconstruction through the 1870s, helping to keep the institution open. The main administration building that sits in the middle of campus today is named in his honor.

Julia Tutwiler

The 1880s brought a time of change to campus. Education reformer Julia Strudwick Tutwiler joined the faculty in 1881 as co-principal with her uncle, Carlos G. Smith, former president of the University of Alabama. In 1882-83, state lawmakers provided $2,500 for tuition and supplies, making Alabama the first southern state to fund the education of women, an appropriation that Tutwiler and state legislator Addison Gillespie Smith helped secure. Also in 1883, the school was renamed the Alabama Normal College for Girls and Livingston Female Academy to better reflect the new mission of the institution, providing students with both two-and four-year programs. “Normal training” was the term used at that time to describe teacher education that represented high school plus two years of college education. The Normal College presented its first diplomas at the 1886 commencement exercises.

Julia Tutwiler

The 1880s brought a time of change to campus. Education reformer Julia Strudwick Tutwiler joined the faculty in 1881 as co-principal with her uncle, Carlos G. Smith, former president of the University of Alabama. In 1882-83, state lawmakers provided $2,500 for tuition and supplies, making Alabama the first southern state to fund the education of women, an appropriation that Tutwiler and state legislator Addison Gillespie Smith helped secure. Also in 1883, the school was renamed the Alabama Normal College for Girls and Livingston Female Academy to better reflect the new mission of the institution, providing students with both two-and four-year programs. “Normal training” was the term used at that time to describe teacher education that represented high school plus two years of college education. The Normal College presented its first diplomas at the 1886 commencement exercises.

Alabama Normal College Tennis Team, 1910

Dr. Smith retired in 1886, and Capt. James W. A. Wright, who was Tutwiler’s brother-in-law, was called to be the next co-principal with Tutwiler. Tutwiler gained national exposure for the college with her outspoken advocacy for the education of women, prison reform, and vocational training. She was named president in 1890, after Wright’s retirement, and served until 1910. To this day, she is recognized as not only the first president of the institution but also the only woman to have held the title of president. During her tenure, Tutwiler also aided in establishing the Alabama Girls’ Industrial Institute (now the University of Montevallo) and in having the first women admitted to the University of Alabama in 1893. Indeed, 10 graduates from Tutwiler’s Alabama Normal College, along with an instructor from Livingston, moved into a home, dubbed the Tutwiler Annex, on the University of Alabama campus in the fall of 1898. Two years later, group member Rosa Lawhorn became the first woman to receive a titled degree from the university.

Alabama Normal College Tennis Team, 1910

Dr. Smith retired in 1886, and Capt. James W. A. Wright, who was Tutwiler’s brother-in-law, was called to be the next co-principal with Tutwiler. Tutwiler gained national exposure for the college with her outspoken advocacy for the education of women, prison reform, and vocational training. She was named president in 1890, after Wright’s retirement, and served until 1910. To this day, she is recognized as not only the first president of the institution but also the only woman to have held the title of president. During her tenure, Tutwiler also aided in establishing the Alabama Girls’ Industrial Institute (now the University of Montevallo) and in having the first women admitted to the University of Alabama in 1893. Indeed, 10 graduates from Tutwiler’s Alabama Normal College, along with an instructor from Livingston, moved into a home, dubbed the Tutwiler Annex, on the University of Alabama campus in the fall of 1898. Two years later, group member Rosa Lawhorn became the first woman to receive a titled degree from the university.

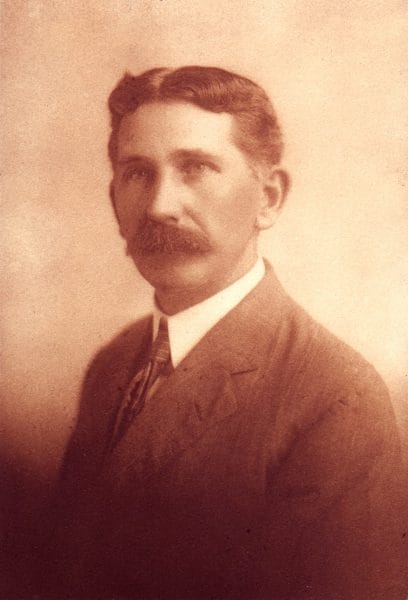

George W. Brock

The new century brought new leadership and again a new name to the school. George William Brock was hired by the trustees in 1907 to oversee the financial affairs of the institution. Following Tutwiler’s retirement in 1910, he assumed the presidency. Alumni began meeting in honor of Tutwiler in 1910 and formed the first alumni association. Under Brock’s guidance, the school officially admitted men as regular students in 1915. Recognizing its commitment to teacher training, the college built Foust Hall in 1922 to provide an example of a modern elementary school building. The building operated as a lab school, where professors at the college taught and their students observed and participated in classroom instruction. The building’s open-air plan with a central courtyard became a building design familiar to many Alabamians. The school grounds were designed by the famed Olmstead Brothers landscape architecture firm, which was commissioned by the state in 1927 to landscape Alabama’s normal schools. In 1928, both Bibb Graves Hall and Brock Hall were added to the physical plant under this plan. The following year the Alabama State Board of Education took over supervision of the college as well as all other normal schools of Alabama, and renamed it the Livingston State Teachers College. Also under Brock, the school organized a student newspaper, Campus Lights, in 1929 and a football team in 1931. With striped uniforms, the institution took the tiger as its mascot, and the sports teams continue today to be known as the UWA Tigers, with school colors of red and white. Brock retired in 1936 and was succeeded by Noble Franklin Greenhill, who served until 1944.

George W. Brock

The new century brought new leadership and again a new name to the school. George William Brock was hired by the trustees in 1907 to oversee the financial affairs of the institution. Following Tutwiler’s retirement in 1910, he assumed the presidency. Alumni began meeting in honor of Tutwiler in 1910 and formed the first alumni association. Under Brock’s guidance, the school officially admitted men as regular students in 1915. Recognizing its commitment to teacher training, the college built Foust Hall in 1922 to provide an example of a modern elementary school building. The building operated as a lab school, where professors at the college taught and their students observed and participated in classroom instruction. The building’s open-air plan with a central courtyard became a building design familiar to many Alabamians. The school grounds were designed by the famed Olmstead Brothers landscape architecture firm, which was commissioned by the state in 1927 to landscape Alabama’s normal schools. In 1928, both Bibb Graves Hall and Brock Hall were added to the physical plant under this plan. The following year the Alabama State Board of Education took over supervision of the college as well as all other normal schools of Alabama, and renamed it the Livingston State Teachers College. Also under Brock, the school organized a student newspaper, Campus Lights, in 1929 and a football team in 1931. With striped uniforms, the institution took the tiger as its mascot, and the sports teams continue today to be known as the UWA Tigers, with school colors of red and white. Brock retired in 1936 and was succeeded by Noble Franklin Greenhill, who served until 1944.

Under Greenhill’s administration, campus life began to flourish with social sororities and intercollegiate sports in baseball, basketball, and football. The first homecoming celebration was held in 1939. World War II brought a decline in enrollment, and the school was near closure when William Wilson Hill assumed the presidency in 1944. He began with only 92 students; recruiting was a priority and returning servicemen were at the top of his list. With more men on campus, the interest in sports was revived and Tiger Stadium was built in 1952. It was also during Hill’s tenure (1944-53) that the first campus fraternities were established.

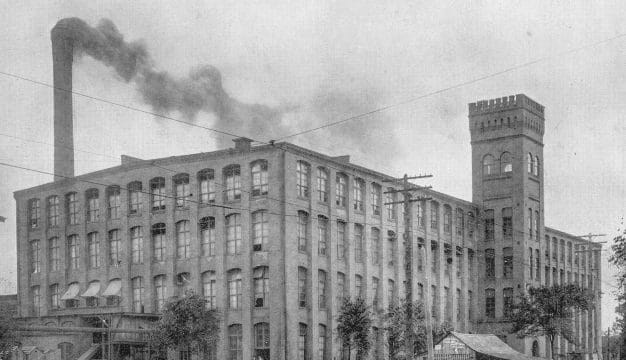

Livingston State Teachers College, 1953

The institution continued to gain a reputation for teacher education in both the region and the state through the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The mission of the institution was broadened again in 1957, when, under the leadership of Delos Culp (1954-63), the school’s name was changed to Livingston State College and was authorized by the state board of education to award master’s degrees in professional education under a new graduate division. Kelly Hester Land was awarded the first master’s degree, and a writing scholarship competition and building are named for her. Under John E. Deloney (1963-73), the campus grew significantly, expanding to more than 540 acres, with a 54-acre lake surrounded by nature trails for the enjoyment of both the campus and the community. In 1967, the institution was renamed Livingston University (LU) by an act of the state legislature. In 1969, Liza James Howard became the first African-American to attend and graduate from the school. In Howard’s honor, several alumni chartered the minority chapter of the school’s National Alumni Association in her name. In Deloney’s last years, the football team won a national championship in the National AIA Conference and were co-champions of the Gulf South Conference.

Livingston State Teachers College, 1953

The institution continued to gain a reputation for teacher education in both the region and the state through the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The mission of the institution was broadened again in 1957, when, under the leadership of Delos Culp (1954-63), the school’s name was changed to Livingston State College and was authorized by the state board of education to award master’s degrees in professional education under a new graduate division. Kelly Hester Land was awarded the first master’s degree, and a writing scholarship competition and building are named for her. Under John E. Deloney (1963-73), the campus grew significantly, expanding to more than 540 acres, with a 54-acre lake surrounded by nature trails for the enjoyment of both the campus and the community. In 1967, the institution was renamed Livingston University (LU) by an act of the state legislature. In 1969, Liza James Howard became the first African-American to attend and graduate from the school. In Howard’s honor, several alumni chartered the minority chapter of the school’s National Alumni Association in her name. In Deloney’s last years, the football team won a national championship in the National AIA Conference and were co-champions of the Gulf South Conference.

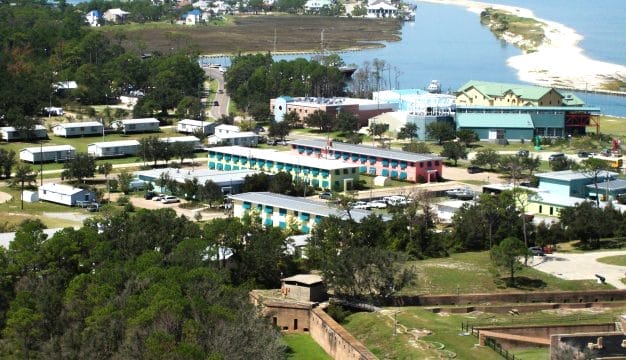

Dauphin Island Sea Lab

In 1973, Asa N. Green (1973-94) became president and oversaw the establishment of the Ira D. Pruitt School of Nursing and dual-degree programs with Auburn University and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He also worked to establish a consortium of 13 schools to create a marine biology program and the Dauphin Island Sea Lab. In addition, buildings were added and renovated across campus. Don C. Hines (1994-98), a former business professor who returned to campus in 1994 to assume the post of president, brought additional change.

Dauphin Island Sea Lab

In 1973, Asa N. Green (1973-94) became president and oversaw the establishment of the Ira D. Pruitt School of Nursing and dual-degree programs with Auburn University and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He also worked to establish a consortium of 13 schools to create a marine biology program and the Dauphin Island Sea Lab. In addition, buildings were added and renovated across campus. Don C. Hines (1994-98), a former business professor who returned to campus in 1994 to assume the post of president, brought additional change.

Approaching the twenty-first century, the school renewed its commitment as a regional institution focused not only on providing a quality education but also on improving the quality of life for the citizens of West Alabama. To reflect this commitment, the name was changed to the University of West Alabama in 1995. Among students, Hines is most remembered for bringing collegiate rodeo to campus. UWA competes in the Ozark Region and has won regional championships in both the men and women’s divisions. In addition, individual competitors have placed nationally in bull-riding and barrel racing. Hines also brought more computers to campus and established new programs in psychology and forestry.

Ed Roach (1998-2002) assumed the presidency in 1998 and set about integrating technology into every aspect of UWA life. He established the Technology 2000 campaign and helped establish UWA as one of the first wireless institutions in the region. Women’s sports also received a boost under his leadership, and the Softball Complex was completed during this period. In 2002, Richard D. Holland, an alumnus of the institution and a former dean of the College of Sciences and Mathematics, became the first UWA graduate to serve as president. Holland continued with the guiding mission that UWA should serve as a catalyst for change and improvement in the region. Amidst some controversy over his annual evaluation by the Board of Trustees, Holland resigned as president in 2014 and was replaced in 2015 by Ken Tucker, formerly the school’s Dean of the College of Business and Technology.

Black Belt Prairie

The school emphasizes in its educational and practical efforts the unique cultural traditions of the region, along with the natural resources that make the Black Belt a region rich with potential research, economic, and social opportunities. Through numerous outreach initiatives, UWA offers students the opportunity to make a difference in the lives of others in hands-on learning experiences with the Sumter County Nature Trust, the Center for the Study of the Black Belt, the Black Belt Prairie Restoration Initiative, and the Regional Center for Economic Development. From these programs, students continue the activist legacy of its first president, Julia Tutwiler, and explore new ways to learn. In 2012, the university partnered with the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation to move the historic Cedarwood wood-frame home from Greensboro to the campus for restoration and preservation. The structure is a rare example of early nineteenth century architecture from Alabama’s Territorial Period.

Black Belt Prairie

The school emphasizes in its educational and practical efforts the unique cultural traditions of the region, along with the natural resources that make the Black Belt a region rich with potential research, economic, and social opportunities. Through numerous outreach initiatives, UWA offers students the opportunity to make a difference in the lives of others in hands-on learning experiences with the Sumter County Nature Trust, the Center for the Study of the Black Belt, the Black Belt Prairie Restoration Initiative, and the Regional Center for Economic Development. From these programs, students continue the activist legacy of its first president, Julia Tutwiler, and explore new ways to learn. In 2012, the university partnered with the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation to move the historic Cedarwood wood-frame home from Greensboro to the campus for restoration and preservation. The structure is a rare example of early nineteenth century architecture from Alabama’s Territorial Period.

The student population consists of approximately 4,600 students, of which about 1,600 take courses online. The student body has a racial diversity of 60 percent white and 39 percent black. Approximately 55 percent of the student body is female and 45 percent male. Students study in small classes averaging fewer than 60 in traditional lecture courses and 25 or less in writing courses. Freshman students eat lunch with the president in class-size groups, and in the fall the entire class has dinner together and attends a fine arts program sponsored by the Sumter County Fine Arts Council.

Further Reading

- Blandon, I. M. E. History of Higher Education of Women in the South Prior to 1860. New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1909.

- Lyon, Ralph M. A History of Livingston University, 1835-1963. Livingston, Ala.: Livingston University, 1976.