Tuscaloosa Campaign and Bloody Tuesday

The Tuscaloosa Campaign was a civil rights initiative that began in March 1964 to integrate Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County. “Bloody Tuesday” refers to the June 9, 1964, civil rights protest march during that campaign that ended in violence at First African Baptist Church, located on Stillman Boulevard. The campaign was launched by Martin Luther King Jr. and led by his former assistant pastor, Theopholius Yelverton “T.Y.” Rogers. Bloody Tuesday was one of the most violent events of the civil rights movement, but many of the city’s public facilities would be integrated by the end of the year.

King understood that integrating Tuscaloosa would carry enormous significance for the civil rights movement. The city, the fourth largest city in Alabama with nearly 19,000 Black residents, representing about one-third of the total population, was the national headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan and home to its Imperial Wizard, Robert Shelton. There were fewer extreme or more powerful white supremacists in the country. The city’s history of racial violence was as intense as any other in the state. On February 3, 1956, Autherine Lucy became the first Black student to attend the University of Alabama, but she fled campus after three days of rioting. On June 11, 1963, Pres. John F. Kennedy federalized the Alabama National Guard to ensure that Gov. George Wallace would comply with a federal court order and allow two admitted Black students, James Alexander Hood of Gadsden and Vivian Juanita Malone of Mobile, to register for classes at the University of Alabama, then the last all-white southern university. Immediately afterwards, Kennedy announced his support for a new civil rights bill. Yet in March 1964, only one Black student remained at the university, the civil rights bill was not yet la w, and Tuscaloosa was as segregated as ever.

King formally declared the start of the Tuscaloosa campaign on March 8, 1964, at First African Baptist Church. Up until this point, local efforts to overturn segregation had been limited and unsuccessful. He made the announcement while preaching the installation sermon for the church’s new pastor, T. Y. Rogers, his 29-year-old protégé and former student, whom he had appointed as his assistant pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery in 1956. King also told the overflow crowd that Rogers, from Coatopa, Sumter County, and a graduate of Alabama State College (present-day Alabama State University), would lead them with the full backing of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). After the service concluded, he informed reporters, for the first time publicly, that his summer plan to redouble attacks on Jim Crow in Alabama included Tuscaloosa as a key target.

Rogers was executive secretary of the Tuscaloosa Citizens for Action Committee (TCAC), the main civil rights organization in the city that was formed in 1962 as an affiliate of the SCLC. He made First African Baptist into the nerve center of the local movement and hosted mass meetings there on Mondays that drew hundreds. He would lead marches and boycotts of segregated businesses and public offices throughout the spring and early summer of 1964. King sent SCLC colleagues to help Rogers, including Andrew Young, Cordy Tindell “C.T.” Vivian, James Bevel, and Dick Gregory. As TCAC protests grew, white resistance stiffened. Whites met marchers with heckles and threats, shot at them with pellet guns, doused them with acid, and beat them while police mostly ignored the violence. Tensions came to a head on June 9, when Rogers, in defiance of local police orders, called for a massive march on the courthouse. Law enforcement and white citizens responded violently in the hope of killing the desegregation effort once and for all.

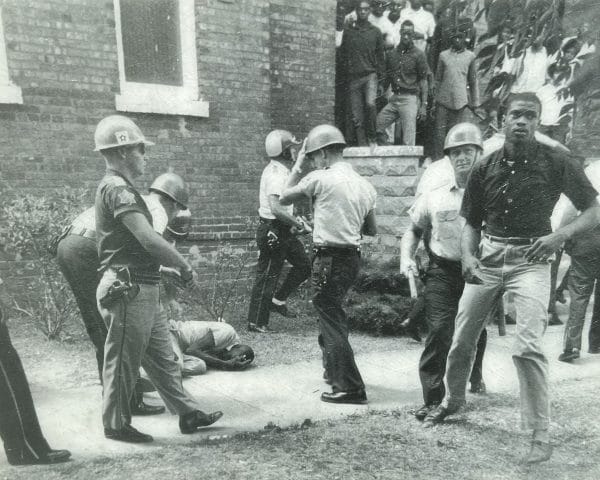

The 600 Black marchers, assembled at First African Baptist, never made it to the courthouse. Approximately 70 law enforcement officers, backed up by nearly 200 deputized white citizens, Klansmen, and white onlookers, herded them into the church and proceeded to smash its stained-glass windows and flood its sanctuary with water from a fire hose. Then, they lobbed teargas grenades inside. As people burst from the church, disorientated and soaked, police beat and arrested as many as they could grab. They donned gas masks and swept the church, expelling those hiding in back rooms and offices. Nearly 100 went to jail, 33 were admitted to the local hospital, and many more sought aid at a nearby barbershop. Locals quickly dubbed the day “Bloody Tuesday” because of its level of racial violence. It marked the peak of white resistance during the Tuscaloosa civil rights campaign.

Despite the violence and mass arrests on Bloody Tuesday, Rogers and TCAC broke the color line by the end of the year. Continued protests, coupled with the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed on July 2 that outlawed racial segregation in public facilities, federal court orders, and the Klan’s declining influence in the city and the state, led to the desegregation of most public spaces in the city. Their victory made possible the later integration of public schools in 1979 and the city commission and county commission in 1985. “Bloody Tuesday” is one of the most violent days of the civil rights movement. It also represents one of the largest attacks on a Black church by law enforcement and white citizens. Occurring between the Birmingham Campaign in spring 1963 and the Selma-to-Montgomery marches in March 1965, it marked the steady growth of Black protests in smaller cities and towns, on the one hand, and the expansion of aggressive policing tactics, on the other. Yet the history of Bloody Tuesday has remained largely unknown outside of the circle of survivors and their families because King, after receiving word of the violence while resting at his home in Atlanta, decided not to come to Tuscaloosa. Instead, he kept to his original itinerary and returned to St. Augustine, where he had been conducting a protest since May. He sent James Bevel, an SCLC leader and a veteran of the effort to desegregate Birmingham, in his place. But Bevel was not a media magnet. Newspapers initially reported on Bloody Tuesday but quickly turned to stories deemed more important, such as the disappearance of three civil rights workers in Mississippi and Freedom Summer. Recently, survivors, working with city and state officials, have begun to draw public and scholarly attention to the Tuscaloosa campaign and Bloody Tuesday. Many of the sites related to the events are featured on the Tuscaloosa Civil Rights Trail, a self-guided walking tour of the city developed by the Tuscaloosa Civil Rights History & Reconciliation Foundation.

Further Reading

- Cobb, Jr., Charles E. This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Right Movement Possible. New York: Basic Books, 2014.