Battle of Columbus

The Civil War Battle of Columbus took place on Sunday, April 16, 1865, resulting in the Federal capture of Columbus, Georgia, and the destruction of its important Confederate industrial complex. The fight also marked the final of the series of battles won by Federal cavalry under the overall command of Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson as they swept through Alabama and into Georgia in March and April of 1865. Featuring a rare nighttime attack, the battle took place on both the Alabama and Georgia banks of the Chattahoochee River, which marks the border between those states.

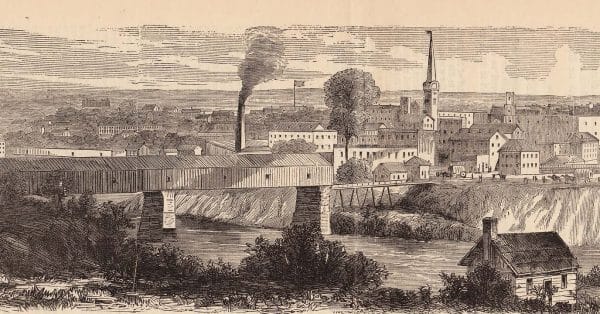

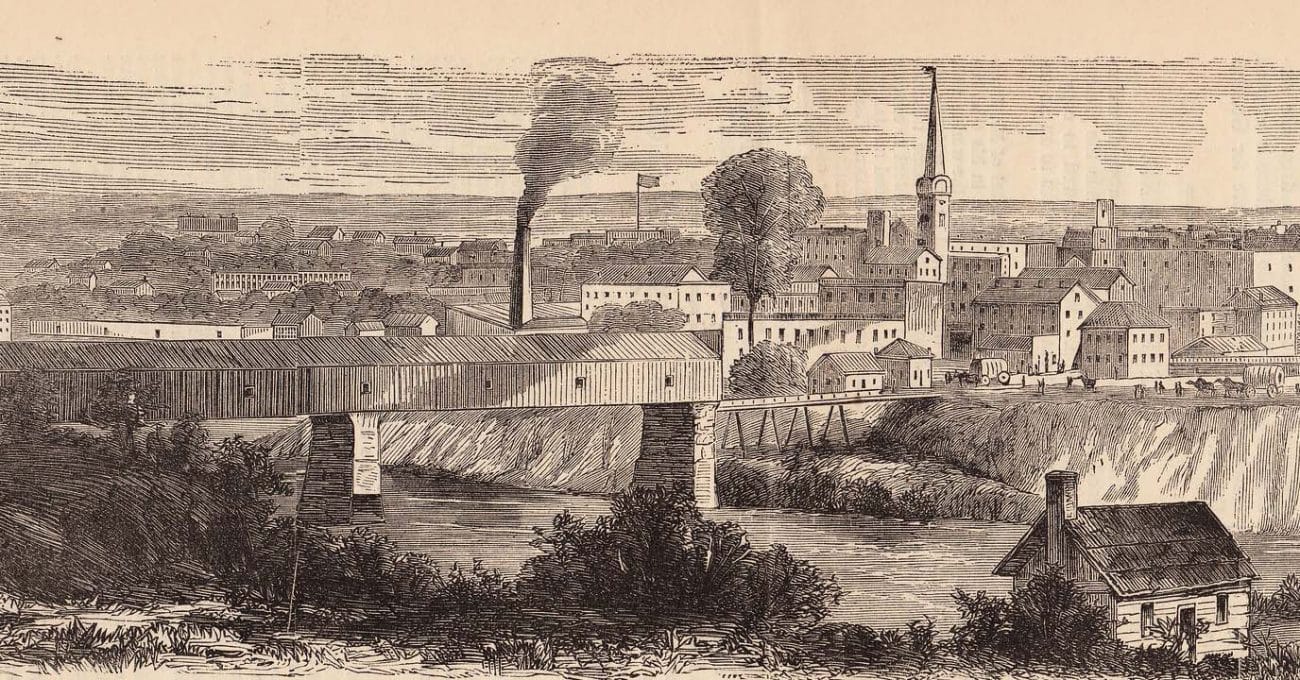

By the spring of 1865, Columbus stood as one of the top Federal military targets in what remained of the Confederacy because of its strategic significance. It was situated at the head of navigation of the Chattahoochee River and was a transport hub for one of the South’s primary cotton production areas with one of the last railroads to remain in operation in the region. More importantly, its concentration of military industrial sites made Columbus of immediate concern to Wilson after his capture of Selma (April 2) and Montgomery (April 12). As one of the most productive ordnance and equipment manufacturing centers in the South throughout the war, the facilities at Columbus were vital to any chance of a continued Confederate war effort.

Among dozens of establishments producing items for the Confederacy at Columbus were textile mills manufacturing cloth for uniforms and factories making rifles, pistols, cannons, swords, and a wide range of ammunition, as well as shoes, saddles, belts, buckles, bayonets, and a host of assorted other items. The site also housed one of the Confederacy’s major steam boiler works and a naval yard producing the last ironclad gunboat for the Confederate Navy. The city’s population had swelled to approximately 20,000 by the time of Wilson’s raid, more than double its prewar number, owing to a massive influx of war industry workers and refugees from other areas of the South.

Although Wilson commanded well over 12,000 men in total, only advance elements of his Fourth Division, under the command of Maj. Gen. Emory Upton, fought at Columbus. This division included veteran troopers from Missouri, Iowa, and Ohio units, numbering about 2,800 men in all. To contest their advance on Columbus, Confederate authorities under the overall command of Gen. Howell Cobb, a former governor of Georgia and U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, had hastily assembled a force comprised of remnants of veteran units paired with an assemblage of mostly ill-trained and poorly equipped conscripts; a motley force of perhaps 3,300 men.

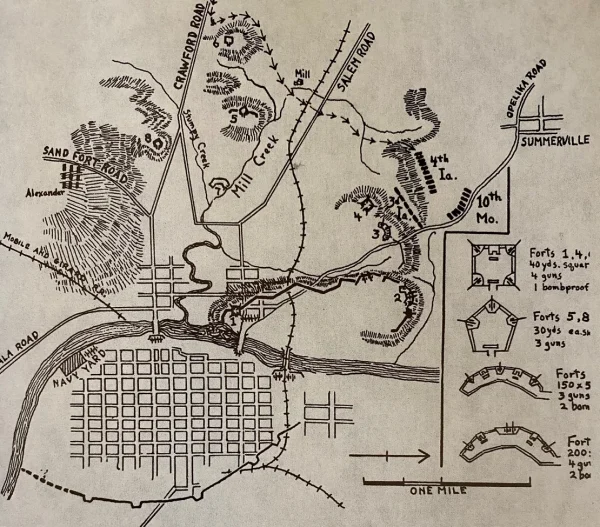

Owing to the geography of the region, most of the defenses of Columbus lay on the Alabama, or western, bank of the Chattahoochee at Girard (present-day Phenix City), Russell County. The small community lay between rugged hills to the north and south overlooking Columbus and thus became focal points for its defense. Confederate commanders concentrated their forces in two small forts northwest of downtown and along a line in front of one of the two pedestrian bridges spanning the Chattahoochee. They also placed a portion of their forces in Columbus itself.

The Battle

Advance elements of Wilson’s force under Upton arrived in the vicinity of Columbus around 2:00 p.m. on April 16, 1865. Taking position on the hills of southern Girard, the Federal forces first attempted to enter the city by storming the southernmost bridge spanning the Chattahoochee at Columbus, known as the City Bridge (located on the site of today’s Dillingham Street Bridge). Their attempt was halted when Confederates ignited the structure, which had been soaked with turpentine prior to their arrival. Later in the afternoon, Wilson arrived on the battlefield and authorized a nighttime attack on the Confederate lines to gain access to the still-intact Franklin Street Bridge (located at the site of today’s 14th Street Pedestrian Bridge). This was an unusual move during the Civil War and brought with it inherent logistical challenges, but Wilson believed his well-disciplined troopers would be able to quickly overrun the scattered Confederate forces in a rapid nighttime strike. He also reasoned that such an attack would expose his men to far less danger.

The Federal attack began about 8:30 p.m. Dismounted troops from the Third and Fifth Iowa Cavalry, under the command of Brig. Gen. Edward F. Winslow, led the advance down Summerville Road towards the Confederate fortifications astride the path. Armed with Spencer repeating rifles, they overwhelmed the surprised defenders in a brief but chaotic fight that produced few casualties despite featuring a tremendous volume of fire. Shaken and unable to see their pursuing attackers, many of the Confederate defenders fled towards the Franklin Street Bridge. Confederate troops attempted to make a stand near the entrance of the bridge at an artillery battery. But, they were outnumbered and could scarcely distinguish friend from foe in the darkness, despite the pale light of some nearby homes and buildings that had been set on fire to illuminate the battlefield. Realizing that their only route of escape across the river lay behind them, many abandoned their position and ran for the span.

Chaos briefly prevailed in the covered bridge as intermingled Federals and Confederates attempted to make their way into Columbus in the dark. Confederates on the Georgia side of the crossing had two cannons in place, loaded with canister and prepared to rake the interior of the bridge should the Federal troops make it that far. They held their fire, though, when they discovered so many of their own men among the mob surging out of the bridge entrance into the streets of Columbus.

A close-quarters fight occurred at the Columbus entrance to the bridge near the Mott House, where the Confederates made a brief last stand. In a doomed attempt to mount a charge, Col. Charles A. L. Lamar, who had come to national notoriety for his recent illegal importation of African slaves aboard the Wanderer in 1858, was killed. Former Confederate secretary of state and then-general Robert Toombs, along with Gen. Cobb, barely outran the attackers in their flight through town as resistance wilted. Some of the Confederate command managed to escape upon a waiting train that pulled out for Macon as the battle ended. Among those wounded in the last moments was Columbus druggist and Confederate captain John S. Pemberton, who would go on to market one of the beverage formulations he invented as Coca-Cola. Shot and slashed by a sword across the abdomen, his life was reputedly sparred by a money belt that deflected some of the force of the blow.

Exact casualty figures for both armies are difficult to determine precisely. The Federal forces lost about 60 men killed in action, and the Confederates are believed to have suffered twice that number. About 1,500 Confederate troops were captured, with the remainder escaping into the night.

A few hours before the fight in Columbus, the other major bridge crossing on the Chattahoochee, about 40 miles north at West Point, had been secured in the Battle of West Point. Col. Oscar Hugh LaGrange’s approximately 3,700-man force there captured Confederate Fort Tyler, manned by only about 150 men, after an all-day fight. Federal forces in the area thereby had free access into the interior of Georgia and one of the last operational areas of the quickly dissolving Confederacy.

Aftermath

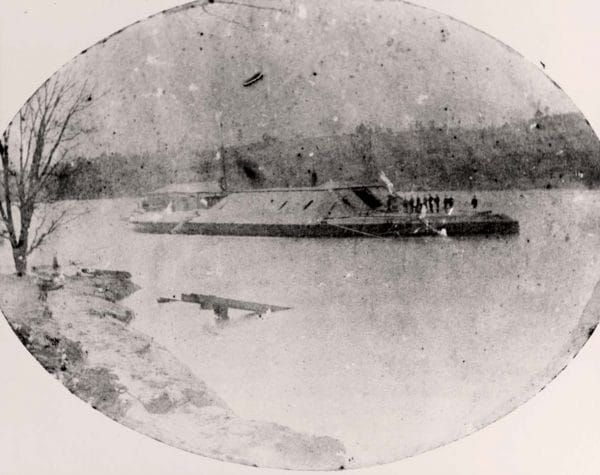

The day after the battle, Wilson ordered that all facilities of military value to the Confederacy be destroyed. His men laid waste to the city’s industrial complex and set ablaze the CSS Jackson and let it drift downriver. Hundreds of bales of cotton and thousands of rounds of ammunition were destroyed and dozens of stores were looted by troopers and unrestrained civilians. After finishing his work in Columbus, Wilson moved east to Macon, which he occupied without resistance and where he learned of the collapse of other Confederate armies. Detachments of Wilson’s men spent the closing days of the war pursuing Pres. Jefferson Davis and his entourage as it made its way through southern Georgia, capturing both him and the commander of Camp Sumter Prison (Andersonville), Henry Wirz.

Further Reading

- Causey, Virginia E. Red Clay, White Water, and Blues: A History of Columbus, Georgia. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019.

- Dameron, J. David. The Battle of Columbus: April 16-17, 1865. Columbus: Southeast Research Publishing, LLC, 2017.

- Jones, James Pickett. Yankee Blitzkrieg: Wilson’s Raid Through Alabama and Georgia. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000.

- Misulia, Charles. Columbus, Georgia 1865: The Last True Battle of the Civil War. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2010.

- Scott, William Forse. The Story of a Cavalry Regiment: The Career of the Fourth Iowa Veteran Volunteers. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893.