Bob Zellner

Civil rights activist John Robert "Bob" Zellner (1939- ) was the first white field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), for which he organized various workshops that taught non-violent strategies and techniques for participating in sit-ins and protests. During his time as civil rights activist, Zellner was beaten and jailed multiple times. He has continued to speak publicly about his experience and how people must continue to promote justice and freedom in the United States and internationally.

Zellner was born on April 5, 1939, in Jay, Florida, to James Abraham Zellner, a Methodist preacher, and Ruby Rachel Hardy, a schoolteacher. He had four brothers. In his early life, the family moved often when his father was relocated to different churches, but he was largely raised in southwest Alabama. Zellner's father, grandfather, and uncles were members of the Ku Klux Klan, but he remained unaware of the Klan and racial hatred when he was younger. In the mid-1930s, his father traveled to Europe to aid the Jewish underground and preach the Gospel as Nazi and antisemitic ideologies spread. He spent months without meeting anyone who spoke English until he came across a group of Black gospel singers supporting the Jewish underground. As they preached, lived, and ate together, he came to reject the racist beliefs with which he was raised. After returning home, he left the Ku Klux Klan and raised his children to reject racist views.

Zellner started school in 1945 in Slocomb, Geneva County, where he repeated the first grade before moving to Loxley, Baldwin County. Zellner suffered from undiagnosed dyslexia, adding to his poor academic achievements early on. Zellner grew up mostly in East Brewton, Escambia County, where his family moved in 1955 after his father finished his ministry in Daphne, Baldwin County. During this time, Zellner began to learn about race and class. When working in a small country store, his boss noticed he was respectful towards an elderly Black couple and told him he could get in trouble if he was seen being too respectful of Black people. Zellner attended W. S. Neil High School in Brewton and Murphy High School in Mobile. He began developing his own beliefs about race and equality that were different from his peers after Autherine Lucy was expelled from the University of Alabama in 1956. Zellner challenged his classmates about their beliefs, and he was viewed negatively because of his opinions. After graduating in 1957, he entered Huntingdon College in Montgomery, Montgomery County.

In 1960, Zellner and four other Huntingdon classmates were given a sociology assignment to research issues surrounding racism and write a paper that proposed solutions. While working on the assignment, Zellner attended meetings held by black students and met members of SNCC for the first time. He then faced backlash from the college president and most of the administration and even gained the attention of Alabama Attorney General MacDonald Gallion, who told Zellner he had fallen under the influence of Communists. His activism gained notice and he later received a call from civil rights activist Anne Braden, who convinced him to join SNCC. He graduated in 1961 with a degree in psychology and sociology.

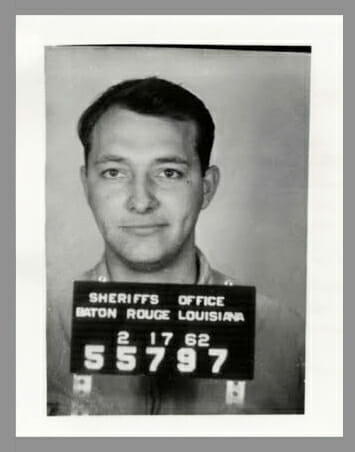

In the fall of 1961, Zellner was hired as the first white field secretary for SNCC and was tasked with reaching out to white students at southern colleges and universities. One of Zellner's first assignments was to visit McComb, Mississippi, along with other SNCC members to attend a staff meeting. While he was there, Burglund High School students organized a march to protest the murder of voting rights activist Herbert Lee, who was shot by Mississippi state representative Eugene H. Hurst during an altercation. An all-white jury ruled the murder justifiable. The students were also protesting the arrest and expulsion of two classmates who had participated in a sit-in at the McComb Greyhound Station. Zellner's involvement in the march made him a target of white supremacists, who beat him unconscious and attempted to lynch him. He was also imprisoned for joining in the protest. In 1962, Zellner and SNCC chair Charles McDew were imprisoned for a month for "criminal anarchy" in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, after they visited imprisoned Freedom Rider Don Diamond in jail.

Returning to Alabama in 1962, Zellner organized workshops on nonviolence for students at Talladega College in Talladega, Talladega County. The workshops aimed to prepare students for lunch-counter sit-ins and marches. Some workshops focused on the philosophy of non-violence while others role-played scenarios participants could encounter during these sit-ins. In June 1963, SNCC representatives and Zellner held similar workshops and took part in demonstrations to promote equality and integration in Danville, Virginia. He and others, including his future wife, SNCC staffer Dorothy "Dottie" Miller, were subjected to police brutality and fire hoses. That August, he and Miller married and together would raise two daughters. In spring 1964, Zellner and Dottie began coordinating volunteers for SNCC's Greenwood, Mississippi, Freedom Schools, which were created to educate attendees about Black leaders, Black history, and non-violent resistance techniques.

In 1966, Zellner and Dottie began to develop the GROW (Grassroots Organizing Work) project aimed at organizing poor and working-class Blacks and whites in the Deep South about changes they could make to improve their living situation. (Around this time, Dottie reportedly helped design the symbol of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, which grew out of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization.) In May 1967, Zellner discussed GROW with SNCC leaders but was rebuffed because of SNCC's 1966 decision to be an all-Black organization. He left SNCC that year owing to disagreements about his position on the staff.

Zellner and Dottie then moved to New Orleans and over the next ten years ran their GROW project in coordination with the Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF), the educational wing of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare (SCHW). GROW later focused on assisting factory workers and unionization efforts. Toward the end of the GROW project, Zellner and Dottie separated in 1979 and divorced in 1990.

In the 1980s, Zellner did some film work while also writing, traveling, and lecturing. Encouraged by a former colleague, he enrolled in a Ph.D. program in the Tulane University History Department in 1991, writing his dissertation about his experiences as a civil rights worker. During that time, he taught undergraduate history, served as a graduate assistant, and occasionally lectured in the Sociology Department. He completed his studies several years later.

Having settled on Long Island, New York, Zellner married publisher Linda Miller in 1994; they would later divorce. He became involved in a land dispute between developers and the local Shinnecock Indian Nation and was beaten and jailed. He also taught about the history of activism with an emphasis on the freedom movement at local colleges. In 2008, Zellner published his memoir, The Wrong Side of Murder Creek, which was produced as the film Son of the South, with some filming in Montgomery and at Tuskegee University in Tuskegee, Macon County, and released in 2020. In 2013, while living in Wilson, North Carolina, Zellner was arrested during a protest against voter suppression. Zellner returned to southwest Alabama, where he and his wife Pamela Smith run a civil rights consulting business in Fairhope.

Further Reading

- Bryan, G. McLeod. These Few Also Paid a Price: Southern Whites Who Fought for Civil Rights. Macon. Ga.: Mercer University Press, 2001.

- Zellner, Bob, and Constance Curry. The Wrong Side of Murder Creek: A White Southerner in the Freedom Movement. Montgomery, Ala.: NewSouth Books, 2008.