Taverns on the Old Federal Road

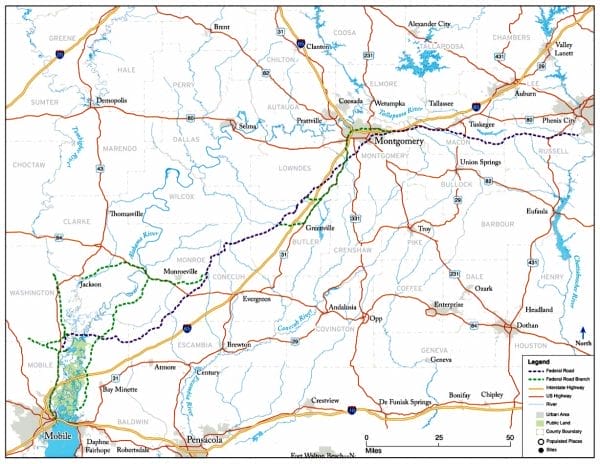

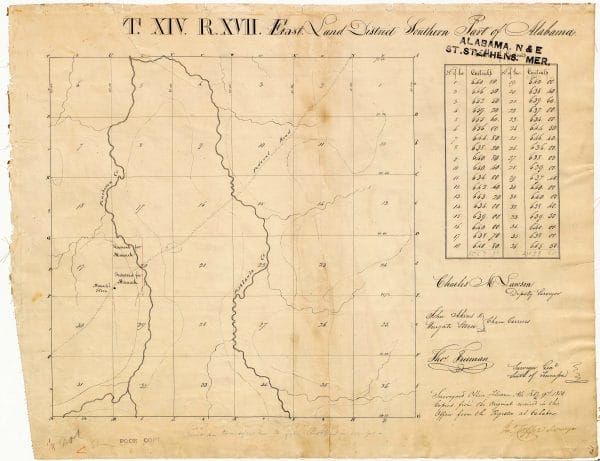

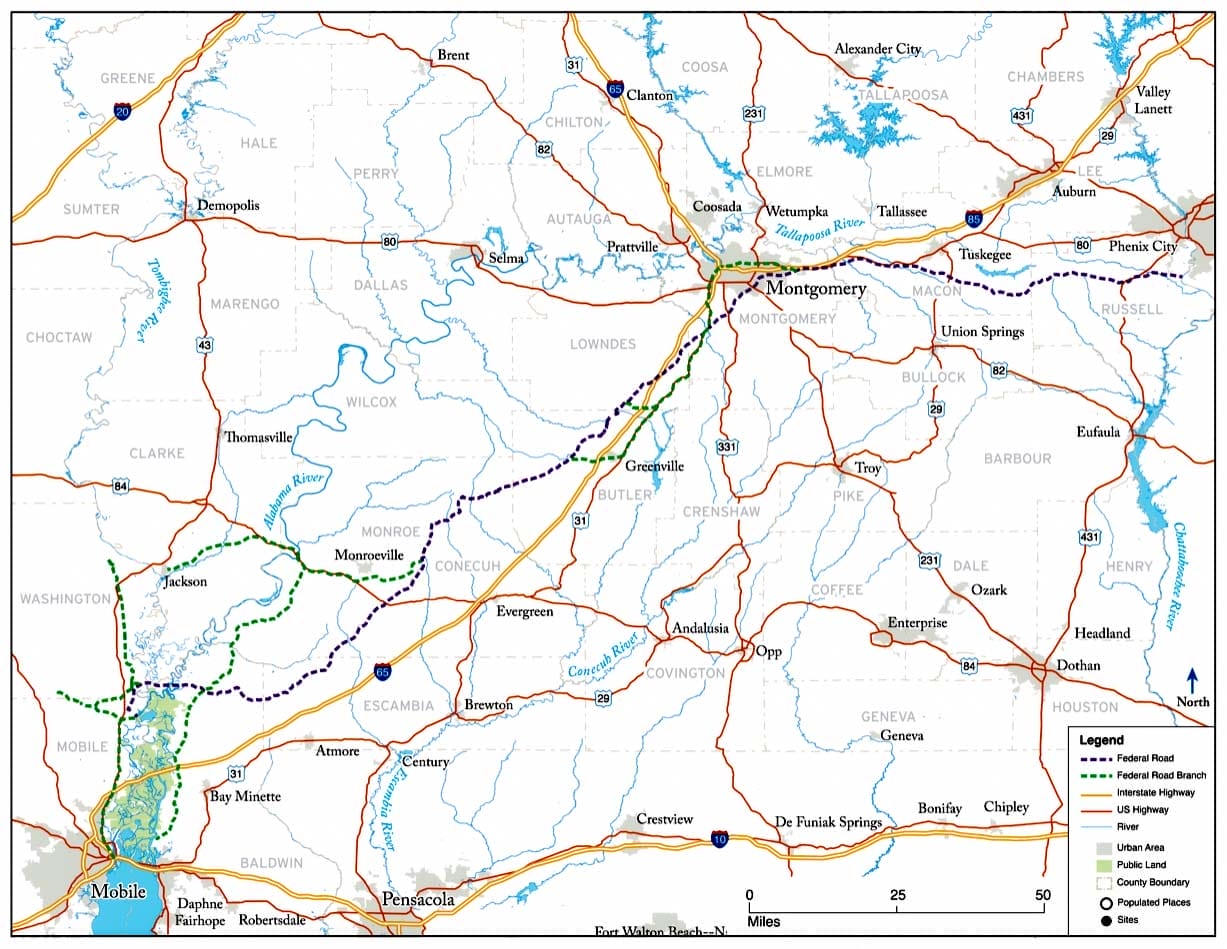

The Federal Road was a historic route through the Southeast that was initially constructed to provide a critical link between Washington, D.C., and New Orleans for the U.S. Postal Service. In what is now the state of Alabama, the road ran from Fort Mitchell (present-day Russell County), in the territory of the Creek Nation until 1832, to Fort Stoddert, in present-day Mobile County. After the defeat of the Creeks in the Creek War of 1813-14, thousands of people, free and enslaved, traveled the route in what was then the Mississippi Territory and subsequently the Alabama Territory during the land rush known as “Alabama Fever.” Taverns provided welcome respite for these travelers and were an integral part of the route. Most taverns on the road were located in the Creek Nation, bordered in the east by the Chattahoochee River and in the west at Line Creek, prior to 1832.

The 1805 First Treaty of Washington between the federal government and the Creek Nation allowed white settlers to enter Creek territory. It also enabled and made Creek chiefs responsible for maintaining taverns, inns, stagecoach stops, and ferries, with prices regulated by Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins and later his successor. Several of the taverns were operated by white men married to Creek women. As numerous people traveled the Federal Road for various purposes, they could stop at taverns purposely located 14 to 16 miles apart along the route. Early on, the businesses were known as “stands” and were traditional Native American structures. They would evolve into log and clapboard huts and later “dog trot” log houses. Taverns not only provided a means of protection for travelers after sunset, they also became centers of entertainment and socializing for the wealthy tourists, business people, and government officials who largely used the route. Taverns provided a welcome rest for those who could afford them.

It was impractical and dangerous to traverse the entire route of the Old Federal Road nonstop, so taverns provided much-needed way stations for those seeking rest from their travels. It was not uncommon for travelers to spend several days at one location. As travel increased along the Federal Road, more taverns began to appear. Some taverns, including Lucas’s Tavern, were known for excellent hospitality and first-class service, whereas other taverns merely provided shelter and an occasional meal. A few earned a reputation for their inhospitality and poor services and exorbitant prices.

The variety of people, places, and foods present in early Alabama came together under the tavern roof to produce an immersion in Alabama’s diverse culture. Tavern food reflected the diversity within Alabama’s culinary traditions. Native Americans and enslaved African Americans often cooked and served the meals. The offerings represented what became known as southern cuisine and reflected the bounties of Alabama agriculture and wild foods. Typical dishes included bacon, eggs, roasted chicken, cream, and butter. Additionally, indigenous foods were also served, including corn, from which corn cakes and cornbread was made, venison, and sofkee, a gruel made from hominy (corn kernels soaked and softened in wood-ash lye).

Travel on the Federal Road evolved as other sections in Alabama were expanded and opened, railroad and steamboat traffic increased, forts built during the Creek War were abandoned, and the forced removal of the Creek Indians from the state made travel safer for whites. Over time, stands, taverns, stage stops, and inns fell into disuse and disrepair, and some became private residences. Much of what is known about the taverns comes from personal anecdotes by individuals who traveled the road or stayed at a tavern, several studies on the Federal Road, and an archeological survey of the road sponsored by the Alabama Department of Transportation and performed by the University of South Alabama Center for Archaeological Studies in 2012.

In addition to those listed below, there were other taverns, inns, stage stops, and private homes that provided food and lodging along the Federal Road, but there is little to no evidence of their existence. A few, such as those operated by Charles Stewart and P. Downey near the area where present-day Conecuh, Escambia, and Monroe Counties converge, can be found on a few old maps or in brief mentions in traveler accounts, but some remain otherwise undocumented.

SOME NOTABLE TAVERNS

Russell County

Anthony’s Tavern/Crowell’s Tavern/Johnson’s (Johnston’s) Hotel

This tavern was located at Fort Mitchell, present-day Russell County, at the start of a main branch of the Federal Road when traveling west. From 1811 to 1824, it was owned in part by Little Prince (Tastanaki Hopayi), a chief of the Lower Creeks, and run by Capt. Thomas Anthony from 1820 to 1825. The Marquis de Lafayette stayed at this tavern on March 31, 1825, prior to his tour through the Creek Nation. Around 1825, the tavern was taken over by Thomas Crowell, brother of Indian agent and U.S. Army colonel John Crowell. Thomas Crowell operated the tavern until 1830, when it taken over by Maj. James Johnson (or Johnston in some sources) and was known as Johnson’s Hotel. Jacob Motte, an Army surgeon during the Second Creek War, described Johnson’s as “nothing more than a log house.” Noted writer Anne Royall visited the tavern under Johnson’s ownership during her travels of the southeastern United States. She wrote in her diary that while she avoided the boisterous tavern area, she found her lodgings to be amenable. Royall mentioned that two Indian women, most likely Creek, tended to her and provided her with tea, pen and ink, and a candle to write by. It was likely abandoned in 1840 when federal troops left Fort Mitchell.

Haynes Crabtree’s Tavern

A one-story log cabin with three beds, Crabtree’s Tavern was located a few miles west of Fort Mitchell at the confluence of the Big and Little Uchee Creeks at the location of a natural bridge initially known as Uchee Bridge. It opened in 1820 and went through several different owners and names. Among them were Col. George Lovett, a wealthy Creek chief, and Thomas Anthony, who also ran an adjacent store. The tavern was owned by Haynes Crabtree when the Marquis de Lafayette made his first overnight stop in the Creek Nation there.

Royston’s Tavern

Located about 15 miles west of the Chattahoochee River, this establishment was operated by a Mr. Royston from 1825 until 1836. It was adjacent to Sand Fort, an earth and stockade fort constructed by members of the Georgia Militia in 1814 during the Creek War. Some historians conjecture that the tavern was owned by a Creek Indian because it ceased operating around the time of the Creeks forced removal. It was described as “a tolerable country inn” by James Stuart of Scotland in a modern-day collection of early traveler accounts of the road. The exact location of the fort and tavern, perhaps a few miles north of Seale, is unknown.

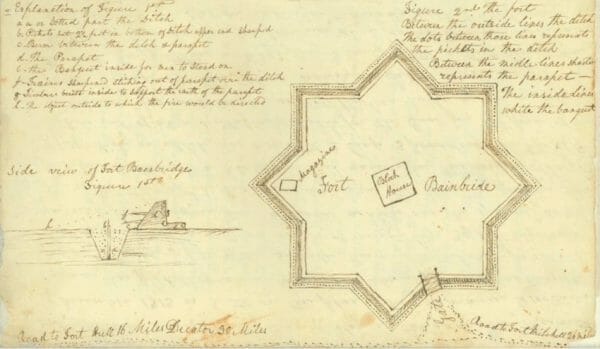

Lewis’s Tavern

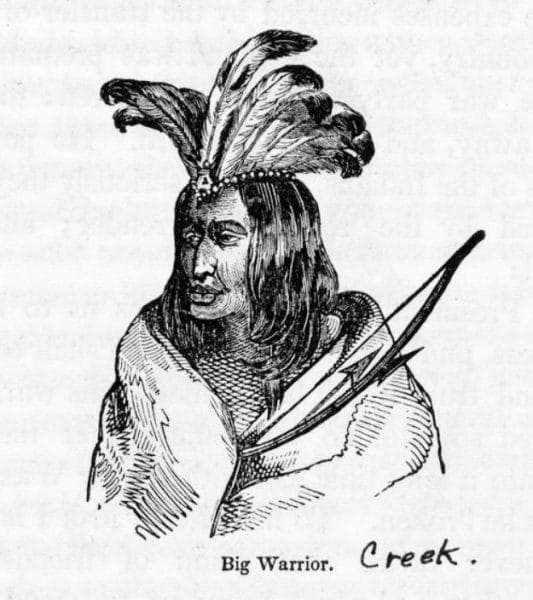

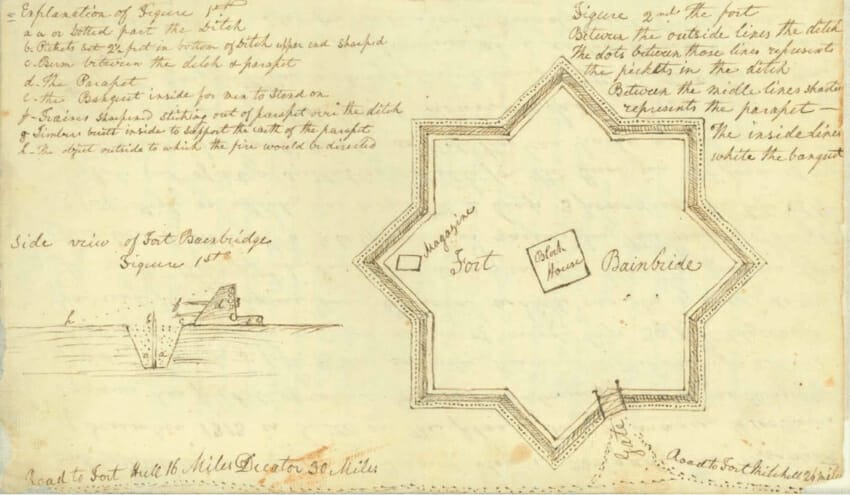

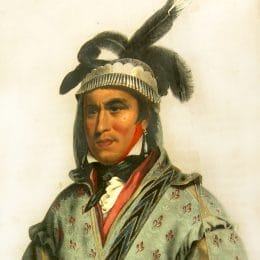

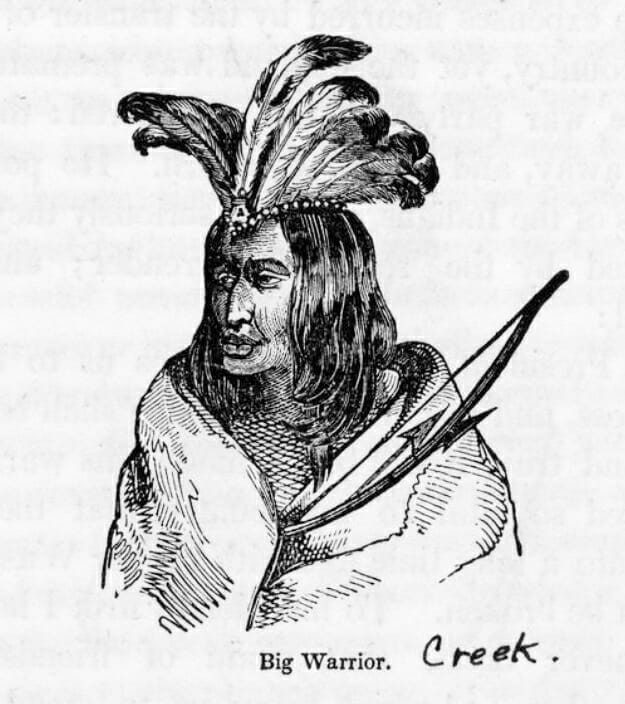

Located near Fort Bainbridge just north of present-day Hurtsboro, Russell County, about 15 miles west of Royston’s Tavern, Lewis’s Tavern became known as a preferred rest-stop along the Federal Road. It was owned and operated between 1816 and 1827 by Capt. Kendall Lewis and his wife, with her father, Big Warrior, as a silent partner. Her name was not recorded in contemporary accounts. Big Warrior (Tustanagee Thlucco) was principal chief of the Tuckabatchee Creeks until his death in 1825. Lewis served as a lieutenant of scouts under Benjamin Hawkins and as assistant commissary of purchases at Fort Mitchell. He was also reputed to have served as captain of a Georgia regiment in the War of 1812.

The tavern was a double-pen log structure considered one of the best in the Creek Nation. The front rooms served as the social and eating area, and as many as 12 guests could be hosted in the rear rooms. Accounts noted that there were no glass windows, but the guest rooms had shutters. Travelers lauded Lewis for his abilities as host and the high quality of his accommodations and meals prepared by his wife. In addition to a bed for the evening, visitors could enjoy wine, brandy, water, and a meal for less than the government-regulated price of $0.75. Several members of Lafayette’s party stayed here during his tour. By 1833, the tavern was known as Mrs. Harris’s Hotel and by 1835 as Cook’s Tavern.

Macon County

Creek Stand and Warrior Stand/Big Warrior’s Tavern

Warrior Stand (now the unincorporated community of Warriorstand) and Creek Stand (sometimes Creekstand) were two closely associated sites in Macon County that each hosted taverns. Creek Stand Tavern was located about three miles west of Fort Bainbridge, on the line between Macon and Russell Counties. Contemporary histories differ as to whether Creek Stand was operated by Little Prince or owned by Sampson Lanier. Some sources say that Lanier opened it in 1832, which is four years after Little Prince’s death. Five miles to its west at Big Warrior’s home was Big Warrior’s Tavern or Warrior Stand. It was solely owned by Big Warrior from 1805 until his death, perhaps in early March 1825, and hosted Lafayette on the night of April 1. Writer Solomon Franklin “Old Sol” Smith notes that it was operated by Black Warrior in 1832, when he stayed there. Carl Bernhard, Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, noted that Big Warrior’s Tavern was popular among cardplayers and horseracing aficionados during his stay. Big Warrior built and operated the racetrack to the west of Warrior Stand near Fort Hull and some five miles south of Tuskegee. When William Potts visited the tavern in 1828, he observed a traditional Creek method of preparing coffee, in which coffee beans were ground by mortar and pestle and sifted to create a smooth brew. In addition, Potts sampled the Creek dish tuk-like-tokse, which is similar to sour cornbread and made with fermented corn dough.

Walker’s Tavern

Located near Pole Cat Springs just east of Shorter, Walker’s Tavern was operated by one of Big Warrior’s daughters, the wife of Capt. William Walker. It provided an assortment of foods for travelers, including guinea hens, other poultry, and wild meats. In addition, Walker’s Tavern was known for baking good bread, both white and brown. James Buckingham noted in his travel journal that Walker’s Tavern had particularly thin walls and a substandard roof, however. On one night, Buckingham stated that he could listen to other travelers through the walls while rain poured in from holes in the roof. It operated from about 1816 to about 1840.

Montgomery County

Lucas’s Tavern

Lucas’s Tavern was located just north of present-day Waugh and west of Line Creek, the boundary between the United States and the Creek Nation from the time of the 1814 Treaty of Fort Jackson to the 1832 Treaty of Cusseta. Built around 1818, the tavern was acquired by Walter and Eliza Lucas in 1820. Lucas’s Tavern was described as “the most celebrated inn on the Federal Road” and hosted a variety of people, including Lafayette on April 2, 1825. Constructed as a two-room dogtrot with a large open hallway in the middle, Lucas’s Tavern was expanded to include two additional rooms after the open hallway was enclosed. After her husband died in a conflict with local Native Americans, Eliza Lucas ran the inn by herself. Travelers stated that she served excellent meals for the government-regulated price of $0.75 and breakfast for $.50. Lucas ran the tavern until 1842, when traffic on the Federal Road substantially decreased. After passing through private hands, the building in which Lucas’s Tavern operated was moved in 1978 to Old Alabama Town in Montgomery, Montgomery County. There, it was renovated and opened in 1980 as the starting point of its “Living Block Tour.”

Old Milly’s Tavern

Also known as Milly’s Stand and Evan’s Tavern, this establishment was located near Abraham Mordecai‘s house on Norcoce Chappo Creek, later called Milly’s Creek, just east of present-day Mount Meigs, Montgomery County. Mordecai is remembered as a very early cotton gin operator, trader, translator, and settler in the area and perhaps one of the first Jewish residents of the state. He is the primary source of information on Milly’s Tavern, which was named for the widow of a British soldier who ran a tavern and a toll bridge and later married Evans. Milly’s Tavern is mentioned in the account of Aaron Burr’s arrest and return to Virginia in 1807 and operated until around 1820. Later travelers often went on to Montgomery to catch a steamboat for Mobile, leaving little accounts of the Federal Road after Evan’s Tavern.

Bonham’s Tavern

Sometimes known as Bonham’s or Bonam’s, this tavern was located in present-day Montgomery County ten miles south of the capital in the unincorporated town of Snowdoun. It was in operation by 1820. The proprietor, Mrs. Bonham, was described by traveler James Stuart as “the worst-tempered female in America.” He noted that she often refrained from serving food at all until the moment the stage was set to arrive. Unwilling to make the stage late, guests either hurriedly ate or left their meals to go cold.

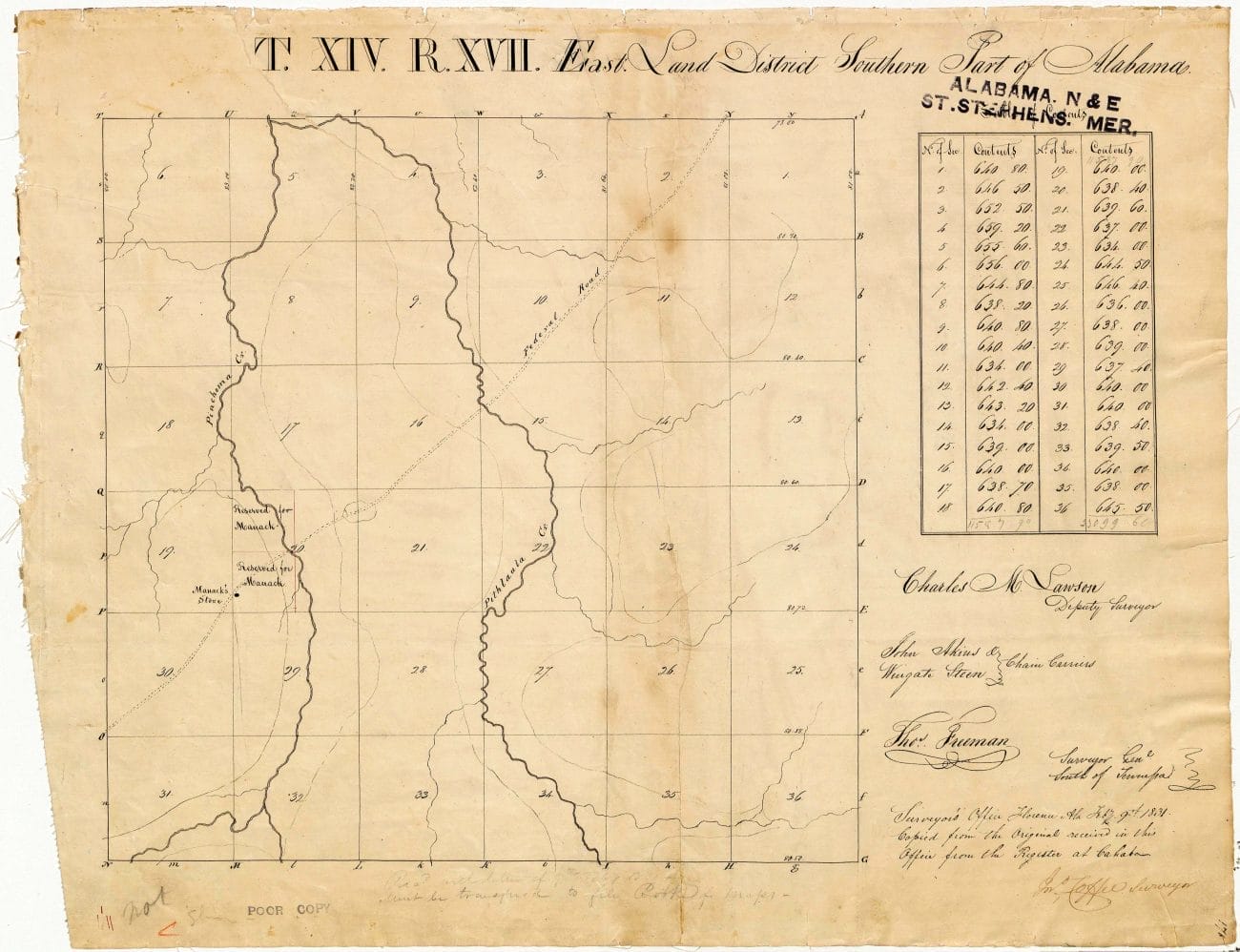

Sam Manack’s Tavern/Moniac’s Tavern

This tavern was established in 1808 by Creek Indian Sam Manack (or Moniac) in present-day west-central Montgomery County near Pinchona (Pinchony) and Pintlala Creeks. It was one of the first licensed taverns on the Federal Road. Also called Sam Manack’s House or the tavern at Pinchony Creek, it was located about 10 miles southwest of Bonham’s Tavern. During the early days of the road, Sam Manack’s House provided a stop for postal workers to switch mounts to keep the mail moving. David Moniac, the son of Sam Manack and a relative of William Weatherford, took over as the proprietor. David was one of the first indigenous people to graduate from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and was killed in the Second Seminole War. Moniac’s Tavern became a popular rest stop for the U.S. Army. In 1813, Gen. James Wilkinson stopped there to write a letter to Benjamin Hawkins about the Creek War. During the war, the Red Stick Creeks destroyed Moniac’s Tavern, after which Moniac sought and received enough compensation from the government to rebuild. By 1819, however, the tavern was abandoned.

Lowndes County

Weatherford’s Stand

Some 12 miles southwest of Manack’s was Weatherford’s Stand, where Red Stick Creek leader William Weatherford made his home after the Creek War. Historians believe the tavern was most likely operated by his brother John Weatherford, a wealthy Creek who worked closely with Americans during the Creek War. Historians note that it appears on just two maps and likely did not operate for very long.

Butler County

The Palings

Named for the palisade of Fort Dale, constructed by Col. Samuel Dale in 1818, in present-day Butler County northwest of present-day Greenville, the tavern site that would become known as the Palings was originally a simple log house located on what English traveler Adam Hodgson described as a “flourishing plantation.” In 1830, James Stuart commented that the tavern only had one “meager” featherbed to accommodate the multiple guests passing through. In 1840, a Col. Wood constructed the tavern that would become known as The Palings, and it became a popular stage stop on the Federal Road. In 1857, Primitive Baptist minister and hymnal author Benjamin Lloyd purchased the property and ran the tavern and hotel until his death three years later. The structure was abandoned afterward. It was documented and photographed in 1935 by the Historic American Buildings Survey and destroyed by fire in 1953.

Conecuh County

Longmire’s Inn

Garrett and Susannah Winn Longmire were early settlers of the present-day unincorporated community of Burnt Corn and are believed to have established Longmire’s Inn not long after arriving in the area in 1816. It was located near Fort Warren, a stockade built for the protection of settlers by another early settler, Maj. Richard Warren of South Carolina, in the vicinity of Pine Orchard, just north of Burnt Corn. Mrs. Longmire was noted in traveler accounts for her medicinal skills.

McMillan’s Tavern

McMillan’s Tavern, a stage stop and tavern, was established south of Burnt Corn by Duncan McMillan, a native of Scotland, likely between 1821 and 1830, on the line dividing Conecuh and Monroe Counties. McMillan is mentioned by fellow Scotsman James Stuart in 1830 as being largely self-sufficient. Nineteenth century artifacts have been recovered at the approximate location of the tavern, now overgrown with pine trees, but were not definitive enough to confirm it was the site of the tavern.

Monroe County

Shearley’s Tavern

Nearing the western terminus of the Federal Road in Alabama, Shearley’s Tavern in Claiborne, Monroe County, was operating by 1819, according to some traveler accounts. Unlike some of the more highly touted stops along the route, Shearley’s was not highly rated among travelers. Judge Stock Thomas of Georgia, for example, found the accommodations at Shearley’s so unbearable in 1819 that he refused to stay longer than one night.

Further Reading

- Benton, Jeffrey C. The Very Worst Road: Travellers’ Accounts of Crossing Alabama’s Old Creek Indian Territory, 1820-1847. Eufaula, Ala.: Historic Chattahoochee Commission of Alabama and Georgia, 1988.

- Brannon, Peter, A. ed. “Early Travel and Some Stage Stops in Alabama.” The Pageant Book: The Spirit of the South. Montgomery, Ala.: Wilson Printing Co.

- Braund, Kathryn E, Gregory A Waselkov, and Raven M. Christopher. The Old Federal Road in Alabama: An Illustrated Guide. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2019.

- Bridges, Edwin C. “‘The Nation’s Guest’: The Marquis de Lafayette’s Tour of Alabama.” Alabama Heritage 102 (Fall 2011): 8-17.

- Henry deLeon Southerland, and Jerry Elijah Brown. 1989. The Federal Road Through Georgia, the Creek Nation, and Alabama, 1806–1836. Tuscaloosa: University Alabama Press.

- McWilliams, Tennant S. “The Marquis and the Myth: Lafayette’s Visit to Alabama, 1825.” Alabama Review 22 (April 1969): 135-146.

- Wright, Lolla, W. “Alabama Appetites.” Alabama Review 17 (January 1964): 22-32.