Alabama Railroads

L&N Railroad in Baldwin County

The history of Alabama and the development of its railroads are deeply intertwined. Beginning with the 1832 opening of the Tuscumbia Railway in Franklin County, the state’s railroads solved transportation problems and created opportunities for schemers and legitimate businessmen alike. Over the next century, railroads tied the various parts of the state together, connected Alabama to the rest of the nation, and made the rise of the Birmingham District possible.

L&N Railroad in Baldwin County

The history of Alabama and the development of its railroads are deeply intertwined. Beginning with the 1832 opening of the Tuscumbia Railway in Franklin County, the state’s railroads solved transportation problems and created opportunities for schemers and legitimate businessmen alike. Over the next century, railroads tied the various parts of the state together, connected Alabama to the rest of the nation, and made the rise of the Birmingham District possible.

Cotton dominated Alabama commerce in the antebellum period and river transport funneled much of it to the port of Mobile. North Alabama planters could use the Tennessee River to reach New Orleans, but Muscle Shoals, near Tuscumbia, formed a major barrier. This impediment prompted construction of the Tuscumbia Railway as a route around the shoals. The first two miles of track opened on June 12, 1832. Initially powered by horses, this pioneering line soon operated the first steam locomotive west of the Alleghenies, the Fulton. The Tuscumbia became part of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, which completed its line between Chattanooga and Memphis in 1858.

Charles Pollard

The state’s second railroad began with merchant and farmer Abner McGehee, who conceived an idea to route Georgia cotton through Montgomery over a railroad between the Alabama city and Columbus, Georgia. The Montgomery Railroad opened its first 12 miles of track in 1840 but soon failed. McGehee and railroad executive Charles Pollard reorganized it as the Montgomery and West Point Railroad (M&WP) and changed its destination to above the Chattahoochee River’s rapids. The M&WP succeeded in part because of federally backed loans and reached West Point, Georgia, in 1851. It also was one of the first rail companies to own and use slave labor for construction, having purchased at least 84 slaves.

Charles Pollard

The state’s second railroad began with merchant and farmer Abner McGehee, who conceived an idea to route Georgia cotton through Montgomery over a railroad between the Alabama city and Columbus, Georgia. The Montgomery Railroad opened its first 12 miles of track in 1840 but soon failed. McGehee and railroad executive Charles Pollard reorganized it as the Montgomery and West Point Railroad (M&WP) and changed its destination to above the Chattahoochee River’s rapids. The M&WP succeeded in part because of federally backed loans and reached West Point, Georgia, in 1851. It also was one of the first rail companies to own and use slave labor for construction, having purchased at least 84 slaves.

Montgomery became the state’s first railroad hub when the Alabama and Florida (A&F) completed its line to Pensacola in 1861. The A&F was the third company to receive newly authorized federal land grants, which gave it alternating plots of land along its route. Another railroad to enter Alabama, the Mobile and Ohio (M&O), shared the first land grants with the Illinois Central Railroad, laying track south from Chicago. The M&O opened its 260-mile line, then the world’s longest, between Mobile and Columbus, Kentucky, in 1861.

The earliest plan for a north-south line dates from about 1836, but construction of a Selma to Knoxville, Tennessee, line, the Alabama and Tennessee River Railroad (A&TR), did not start until 1851. It had reached a few miles north of Talladega when the Civil War began in 1861. Although never completed, the A&TR conveyed much raw material to the arsenal at Selma during the war.

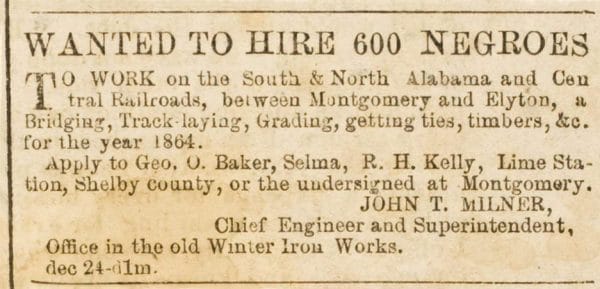

Advertisement for Railroad Laborers

The Civil War brought about massive change on Alabama’s railroads. The Memphis and Charleston (M&C) initially moved Confederate troops and supplies but was largely dismantled in 1861 and 1862 so that its rails and equipment could be used elsewhere in the South and to prevent their use by federal forces. The M&O, A&F, and M&WP participated in the first large-scale troop movement in history. Following the Battle of Shiloh in 1862 in southwest Tennessee, U.S. Army general Don Carlos Buell began marching toward Chattanooga, in southeast Tennessee, alongside the ruined M&C. To counter this, Confederate general Braxton Bragg used these three railroads, along with others in Georgia, to move 25,000 troops and supplies from Tupelo, Mississippi, to the Chattanooga area (a distance of almost 300 miles) in less than a week, arriving well ahead of Buell. As a result of heavy usage, minimal maintenance, and raids by federal troops, particularly those led by Col. Abel Streight (1863), Maj. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau (1864), and Gen. James H. Wilson (1865), the state’s railroads were largely decimated at war’s end.

Advertisement for Railroad Laborers

The Civil War brought about massive change on Alabama’s railroads. The Memphis and Charleston (M&C) initially moved Confederate troops and supplies but was largely dismantled in 1861 and 1862 so that its rails and equipment could be used elsewhere in the South and to prevent their use by federal forces. The M&O, A&F, and M&WP participated in the first large-scale troop movement in history. Following the Battle of Shiloh in 1862 in southwest Tennessee, U.S. Army general Don Carlos Buell began marching toward Chattanooga, in southeast Tennessee, alongside the ruined M&C. To counter this, Confederate general Braxton Bragg used these three railroads, along with others in Georgia, to move 25,000 troops and supplies from Tupelo, Mississippi, to the Chattanooga area (a distance of almost 300 miles) in less than a week, arriving well ahead of Buell. As a result of heavy usage, minimal maintenance, and raids by federal troops, particularly those led by Col. Abel Streight (1863), Maj. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau (1864), and Gen. James H. Wilson (1865), the state’s railroads were largely decimated at war’s end.

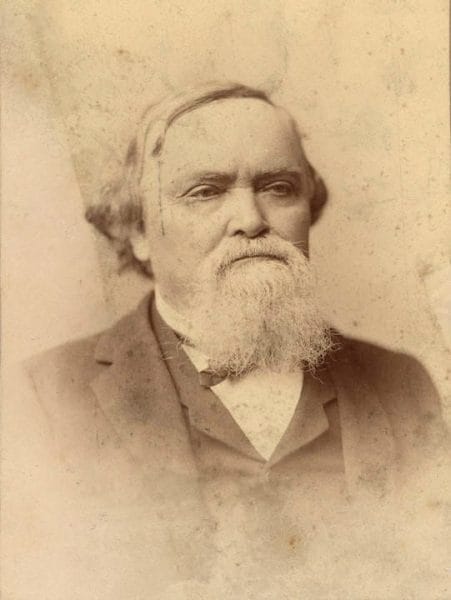

John Turner Milner

Prior to the war, geologists had confirmed that the area around present-day Birmingham contained large deposits of iron ore and coal, but they were worthless without transportation to an industrial center. Supporters of the A&TR lobbied for Chattanooga as that center, but Alabamians Frank Gilmer and John Milner, both of whom had learned railroading on the A&F, envisioned Jones Valley in central Alabama as that industrial base, with a Montgomery–Decatur railroad to serve it. They chartered the Alabama Central Railroad (AC) in 1854, but A&TR backers and the Civil War stalled the project. After the war, Milner reorganized the AC as the South & North Railroad (S&N) and finally began construction in 1869. The company had reached within 66 miles of Decatur when a lack of money to pay bond interest stopped the work. Railroad contractor John Stanton and other A&TR backers schemed to take control of the S&N, but a last-minute infusion of cash from Kentucky-based Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) rescued the S&N and laid rail to Decatur by 1872. There, it connected with another L&N-controlled line, the Nashville and Decatur, giving the expanding L&N its first entry into the state.

John Turner Milner

Prior to the war, geologists had confirmed that the area around present-day Birmingham contained large deposits of iron ore and coal, but they were worthless without transportation to an industrial center. Supporters of the A&TR lobbied for Chattanooga as that center, but Alabamians Frank Gilmer and John Milner, both of whom had learned railroading on the A&F, envisioned Jones Valley in central Alabama as that industrial base, with a Montgomery–Decatur railroad to serve it. They chartered the Alabama Central Railroad (AC) in 1854, but A&TR backers and the Civil War stalled the project. After the war, Milner reorganized the AC as the South & North Railroad (S&N) and finally began construction in 1869. The company had reached within 66 miles of Decatur when a lack of money to pay bond interest stopped the work. Railroad contractor John Stanton and other A&TR backers schemed to take control of the S&N, but a last-minute infusion of cash from Kentucky-based Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) rescued the S&N and laid rail to Decatur by 1872. There, it connected with another L&N-controlled line, the Nashville and Decatur, giving the expanding L&N its first entry into the state.

With the founding of Birmingham in 1871, the area’s fledgling iron industry looked set to prosper, and the L&N expected to earn sizeable revenue from it, but the Panic of 1873 intervened. Led by Milton Smith, the L&N nevertheless continued to back the Birmingham iron industry. The successful use of coke to refine Red Mountain ore in 1876 gave new life to the area, and phenomenal growth occurred throughout the 1880s. Not only did the L&N finally reap large returns on its investment in the S&N, but the revenue also funded its extensions to Mobile and ultimately New Orleans. By 1900, the L&N held a dominant position in Alabama railroading, and Birmingham industrialists began to overtake agricultural interests in state politics, developing an influence that remains strong in the present.

Memphis & Charleston Railroad, ca. 1890

The Birmingham District’s growth attracted other railroad builders seeking their share of the lucrative traffic as well. Chief among these were the East Tennessee, Virginia and, Georgia Railroad (ETV&G) and the Georgia Pacific Railway (GP), a new Atlanta–Greenville, Mississippi, line. The ETV&G was a post-war consolidation of numerous small lines, including the Memphis and Charleston in 1877 and the Selma, Rome, and Dalton Railroad in 1881. The GP, built by railroad executive John Gordon with backing from the Richmond and Danville Railroad (which, along with the ETV&G, was controlled by a holding company known as the Richmond Terminal), reached Birmingham in 1883, and the Mississippi River at Greenville in 1887. In 1880, the Central Railroad and Banking Company decided to extend its system to Birmingham from Columbus, Georgia. Through acquisitions and new construction, its Columbus and Western Railway subsidiary reached Birmingham in 1887. By then, it had also come under Richmond Terminal control.

Memphis & Charleston Railroad, ca. 1890

The Birmingham District’s growth attracted other railroad builders seeking their share of the lucrative traffic as well. Chief among these were the East Tennessee, Virginia and, Georgia Railroad (ETV&G) and the Georgia Pacific Railway (GP), a new Atlanta–Greenville, Mississippi, line. The ETV&G was a post-war consolidation of numerous small lines, including the Memphis and Charleston in 1877 and the Selma, Rome, and Dalton Railroad in 1881. The GP, built by railroad executive John Gordon with backing from the Richmond and Danville Railroad (which, along with the ETV&G, was controlled by a holding company known as the Richmond Terminal), reached Birmingham in 1883, and the Mississippi River at Greenville in 1887. In 1880, the Central Railroad and Banking Company decided to extend its system to Birmingham from Columbus, Georgia. Through acquisitions and new construction, its Columbus and Western Railway subsidiary reached Birmingham in 1887. By then, it had also come under Richmond Terminal control.

Like most southern railroads, these lines were built with a five-foot gauge, referring to the distance between the two rails. Only the M&WP had been built to the standard gauge (4 feet 8 ½ inches) used in the rest of the nation but even it had adopted the five-foot gauge after the Civil War. By the mid-1880s, a change to standard gauge became essential for southern roads to interchange cars with their connections. The M&O agreed to the change in 1885, followed by most other Alabama lines the next year. Having to change gauge yet again, the M&WP may be the only railroad ever to undergo two gauge changes.

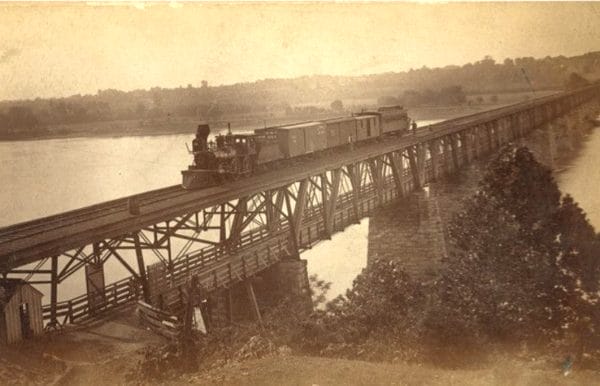

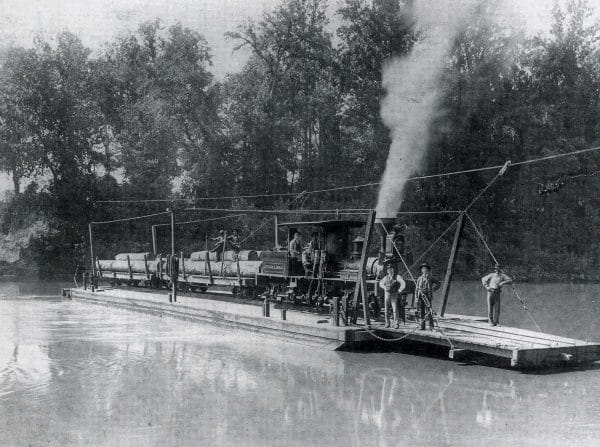

Train Ferry across the Tallapoosa River

The Panic of 1893 drastically reshaped Alabama’s railroads, primarily because of the failure of the Richmond Terminal holding company. Through a convoluted process, the Central Railroad and Banking Company’s lines emerged as the Central of Georgia Railway (C of G) in 1895. The ETV&G and the Alabama Great Southern Railroad, successor to the A&TR, were included in New York financier J. P. Morgan’s new Southern Railway System, formed out of several Richmond Terminal lines in 1894. The L&N was not affected by the Richmond Terminal’s collapse, but it instantly had a strong rival in the new Southern Railway. These two lines would dominate Alabama railroading for almost a century.

Train Ferry across the Tallapoosa River

The Panic of 1893 drastically reshaped Alabama’s railroads, primarily because of the failure of the Richmond Terminal holding company. Through a convoluted process, the Central Railroad and Banking Company’s lines emerged as the Central of Georgia Railway (C of G) in 1895. The ETV&G and the Alabama Great Southern Railroad, successor to the A&TR, were included in New York financier J. P. Morgan’s new Southern Railway System, formed out of several Richmond Terminal lines in 1894. The L&N was not affected by the Richmond Terminal’s collapse, but it instantly had a strong rival in the new Southern Railway. These two lines would dominate Alabama railroading for almost a century.

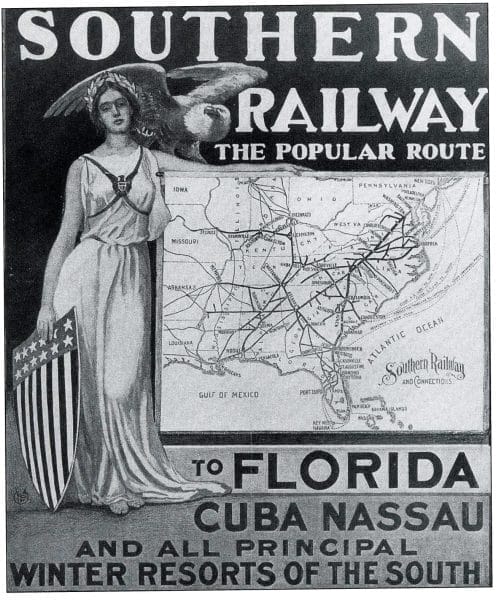

Southern Railway Advertisement

Other lines built into Alabama over the next two decades included: the Kansas City, Memphis and Birmingham (later Frisco), linking Memphis, Tennessee, and Birmingham in 1887; the Alabama Midland (later Atlantic Coast Line), from Bainbridge, Georgia, to Montgomery in 1890; the Mobile and Ohio (later Gulf, Mobile, and Ohio), from Columbus, Mississippi, to Montgomery in 1899; the Seaboard Air Line, connecting Savannah, Georgia, and Montgomery in 1900; the Atlantic and Birmingham Air Line (later Seaboard Air Line, or SAL), from Atlanta to Birmingham in 1904; and the Atlanta, Birmingham, and Atlantic (later the Atlantic Coast Line, or ACL), that linked Manchester, Georgia, and Birmingham in 1910.

Southern Railway Advertisement

Other lines built into Alabama over the next two decades included: the Kansas City, Memphis and Birmingham (later Frisco), linking Memphis, Tennessee, and Birmingham in 1887; the Alabama Midland (later Atlantic Coast Line), from Bainbridge, Georgia, to Montgomery in 1890; the Mobile and Ohio (later Gulf, Mobile, and Ohio), from Columbus, Mississippi, to Montgomery in 1899; the Seaboard Air Line, connecting Savannah, Georgia, and Montgomery in 1900; the Atlantic and Birmingham Air Line (later Seaboard Air Line, or SAL), from Atlanta to Birmingham in 1904; and the Atlanta, Birmingham, and Atlantic (later the Atlantic Coast Line, or ACL), that linked Manchester, Georgia, and Birmingham in 1910.

By 1910, the Alabama railroad map was largely complete, and the iron industry neared maturity as well. Commercial interest in south Alabama’s timber, however, began to grow. The L&N was positioned to build numerous branches to capture the business, but a number of other large railroads and short lines built track in the region as well, and competition for the timber business became stiff.

Whereas many of the lumber short lines ultimately failed, Alabama’s major railroads fared reasonably well during most of the twentieth century, although federal control by the United States Railroad Administration during World War I dealt them a serious financial blow. The railroads also suffered financial setbacks during the Great Depression, but World War II spurred a recovery, and the state’s railroads carried massive amounts of materiel and troops during the conflict.

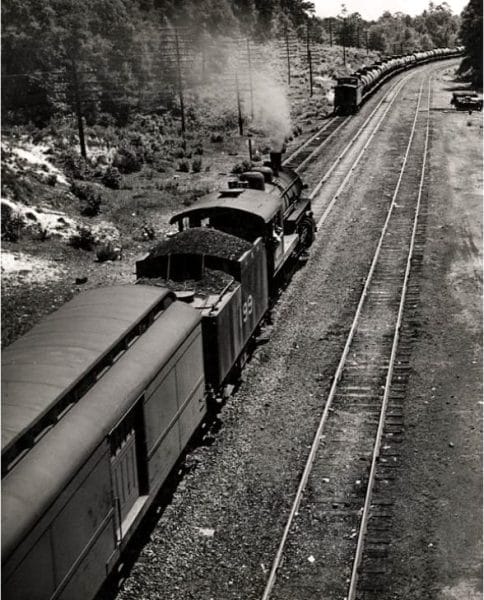

ALCO HH900 #82 Locomotive

The post-war era brought change and consolidation to the state’s railroads. Diesel power replaced steam locomotives, and freight cars grew larger. An unexpected development was the rapid decline in passenger traffic in spite of large investments to re-equip existing passenger trains, such as The Crescent and The Panama Limited and to introduce new ones such as The Humming Bird. These trains remained attractive as sources of transportation throughout most of the 1950s, but a massive increase in the number of automobiles, the new Interstate Highway System, and the advent of jet airliners captured most intercity passenger business. A majority of passenger trains had been discontinued when the federally controlled Amtrak system assumed operation of a skeleton system in 1971. At first the Southern Railway was the only railroad serving Alabama that did not join Amtrak, continuing to run its renamed Southern Crescent until 1979, when it, too, joined Amtrak. Amtrak’s Crescent, serving Anniston, Birmingham, and Tuscaloosa, is now the sole passenger train in the state.

ALCO HH900 #82 Locomotive

The post-war era brought change and consolidation to the state’s railroads. Diesel power replaced steam locomotives, and freight cars grew larger. An unexpected development was the rapid decline in passenger traffic in spite of large investments to re-equip existing passenger trains, such as The Crescent and The Panama Limited and to introduce new ones such as The Humming Bird. These trains remained attractive as sources of transportation throughout most of the 1950s, but a massive increase in the number of automobiles, the new Interstate Highway System, and the advent of jet airliners captured most intercity passenger business. A majority of passenger trains had been discontinued when the federally controlled Amtrak system assumed operation of a skeleton system in 1971. At first the Southern Railway was the only railroad serving Alabama that did not join Amtrak, continuing to run its renamed Southern Crescent until 1979, when it, too, joined Amtrak. Amtrak’s Crescent, serving Anniston, Birmingham, and Tuscaloosa, is now the sole passenger train in the state.

Alabama’s major railroads have been merged into larger companies, starting with Southern’s acquisition of the C of G in 1963, eliminating most historic company names. CSX Transportation (1980) includes the former ACL, SAL, L&N, and Western of Alabama lines, and the Southern is now part of Norfolk Southern Corporation (1982). The BNSF Railway (1996) reaches Birmingham via the former St. Louis-San Francisco (Frisco) track, and the original M&O line into Mobile has been part of Canadian National Railway since 1998. Some smaller railroads remain, but many secondary lines have been abandoned. The collections at the Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum in Calera, Shelby County, and the North Alabama Railroad Museum in Chase, Madison County, encompass a wide variety of locomotives and rail cars spanning all of Alabama’s railroad history.

Further Reading

- Black, Robert C., III. The Railroads of the Confederacy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

- Clemons, Marvin, and Lyle Key. Birmingham Rails: The Last Golden Era. Birmingham: Red Mountain Press, 2007.

- Cline, Wayne. Alabama Railroads. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997.

- Davis, Burke. Southern Railway: Road of the Innovators. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985.

- Hanson, Robert H. The West Point Route: The Atlanta & West Point Rail Road and The Western Railway of Alabama. Lynchburg, Va.: TLC Publishing, 2007.

- Johnson, Robert Wayne. Through the Heart of the South: The Seaboard Air Line Railroad Story. Erin, Ontario: Boston Mills Press, 1995.

- ———. History of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. New York: Macmillan, 1972.

- Stover, John F. The Railroads of the South 1865-1900: A Study in Finance and Control. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955.

External Links

- Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum

- North Alabama Railroad Museum

- Birmingham Mineral Railroad Signs Project

- Foley Railroad Museum

- Stevenson Railroad Depot Museum

- Fort Payne Depot Museum

- Huntsville Depot and Museum

- New Georgia Encyclopedia: Railroads

- Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture: Railroads

- Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture: Louisville and Nashville Railroad