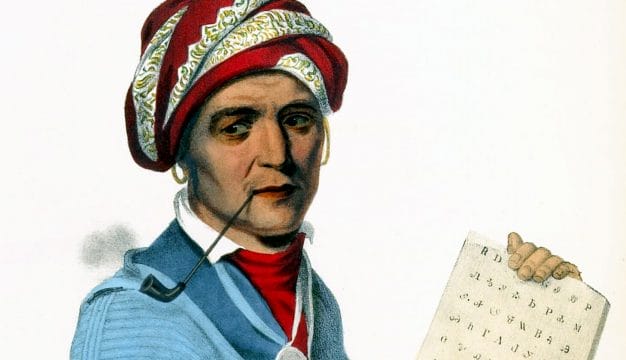

Big Warrior/Tustanagee Thluco

Tustanagee Thlucoo, known among non-Indians as "Big Warrior," was headman of the Upper Creeks of Tuckabatchee and an important member of the Creek National Council from the early 1800s until his death in 1825. Big Warrior served as the speaker for all Upper Creek towns and was an ally in U.S. government's efforts to assimilate Native Americans into European ways of life. He is known for representing the Upper Creeks in the First Treaty of Washington 1805, which ceded a large swath of Creek territory to the U.S. government and created tensions which culminated in the Creek War of 1813-14. After the Creek War, Big Warrior strongly opposed further land concessions.

Tustanagee Thlucco became the mekko (chief) of Tukabatchee, an Upper Creek town in present-day Elmore County about two miles south of Tallassee, in the early 1800s. His name translates to "great warrior" and denotes his high status amongst the Creek peoples. Big Warrior married a Tuckabatchee woman named Tevhoe, the former wife of Upper Creek leader Efau Huajo. Big Warrior and Tevhoe had two sons, Tuskena and Yargee, and at least two daughters whose names are unknown. The Creek Nation was divided between the Upper Creeks and Lower Creeks, with the former occupied territory along the Coosa, Tallapoosa, and Alabama Rivers, and the latter living and trading around the Chattahoochee, Ocmulgee, and Flint River in southwestern Georgia. U.S. army general Thomas Woodward described Big Warrior as the largest man he had ever seen. Standing above six feet, Big Warrior was known for his commanding presence as well as his gift for oration.

In 1805, the United States worked with several Lower Creek leaders, including Little Prince (Tastanaki Hopayi) (of the Creek town Broken Arrow on the Chattahoochee River) and William McIntosh (Tustunnuggee Hutkee), to work out the terms of the First Treaty of Washington (formally known as the Treaty with the Creeks), in which the chiefs ceded a large swath of Creek territory in central Georgia. Big Warrior and other Upper Creek leaders strongly opposed the treaty, creating tensions within the Creek Nation. The United States then constructed a horse path through some of this territory from Ocmulgee River to the Mobile River. This horse path would evolve into the Federal Road, by which thousands of white settlers entered what was then the Mississippi Territory.

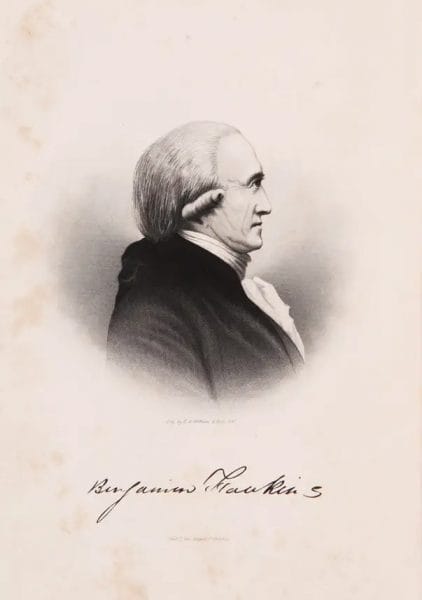

As tensions increased between the United States and indigenous nations throughout what is now the eastern United States, Shawnee chief and warrior Tecumseh traveled from the area of the Ohio River Valley to southeastern tribal nations in 1811 to deliver a message of pan-tribal unity to resist American expansion. Tecumseh hoped to persuade these people to join a confederation of Native Americans to fight back against white encroachment. He arrived in Creek territory in October 1811 during the annual grand Council of the Creek Nation in Tuckabatchee. During his visit, more than 5,000 Creeks attended the meeting, including Sam Moniac, who would serve as a federal guide during the Creek War of 1813-14 and be targeted for retribution during the conflict. Also in attendance was American Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins. Despite Tecumseh's stirring speech, Big Warrior refused to join the confederation in fear of losing American support.

Despite Big Warrior's dismissal of Tecumseh's message of resistance, it was well-received by many Creeks and Seminoles who resented the forced assimilation into American culture. Two natural phenomena, the Great Comet of 1811 and the New Madrid earthquakes of 1811-12, occurred shortly after Tecumseh's visit and were taken by some as signs to follow his message of resistance. Bolstered by these events, Little Warrior (Tuskeegee Tustunnuggee) of the Upper Creek town of Hickory Ground, organized a group of six Upper Creeks in a war party that murdered two white families near the mouth of the Ohio River in February 1813. As a representative of the United States, Benjamin Hawkins demanded justice for the murders and appealed to Big Warrior to carry out the punishment. As tensions mounted amongst Creek peoples over allying with the Americans, Big Warrior hesitated to hand over members of the war party in fear that he would lose respect amongst the Creeks. He also feared retaliation from the American government if he refused to act. In April 1813, Big Warrior wrote to Judge Harry Toulmin to inform him that Little Warrior and seven other men had been executed.

Meanwhile, the anti-assimilationist Creeks, who became known as Red Sticks, allied with Great Britain during the War of 1812. The first major event of the Creek War occurred on July 22, 1813, when the Red Sticks attacked Tuckabatchee. The July 27 Battle of Burnt Corn Creek and August 30 attack on Fort Mims broadened the Creek War to include American forces. With Tuckabatchee destroyed, and the United States military set to attack the Creek Nation, Big Warrior appealed for help from the American government. As the United States was embroiled in the costly war of 1812, Big Warrior offered to pay for American assistance.

Big Warrior and the other members of the National Council were forced to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which declared the Creeks a defeated nation and ceded nearly 22 million acres of Creek land to the United States as payment for war expenses. The treaty exacerbated tensions amongst the Creek peoples, as only American-allied headmen such as Big Warrior signed the agreement. Four years later, the Treaty with the Creeks, 1818, signed at the Creek Agency on the Flint River, fanned Creek discontent because Big Warrior and other American allies, including McIntosh, exchanged two tracts of land in Georgia for a total of $120,000, with $100,000 paid over a ten-year period. After this humiliating experience, Big Warrior worked for compensation for the lost land and opposed all future discussions of land cessions. In 1821, however, McIntosh, Little Prince, and several other Lower Creek leaders signed the Treaty of Indian Springs at McIntosh's thriving tavern in the town of Indian Springs. The treaty ceded the Creeks' remaining land in Georgia and helped to further secure the Federal Road for the American government. McIntosh received a substantial payment and agreed to relocate to lands across the Mississippi. Big Warrior also owned taverns on the Federal road. His daughter and her husband, Capt. Kendall Lewis, operated Lewis's Tavern, with Big Warrior as the owner, near Fort Bainbridge in Russell County, and he also operated Big Warrior's Tavern (also known as Warrior Stand) in Macon County about three miles west of the fort.

Despite the alliance between Big Warrior and McIntosh during the Creek War, Big Warrior and fellow Upper Creek Tuckabatchees were horrified by McIntosh's betrayal. A group of Creek headmen, led by Tuckabatchee leader Opothle Yoholo, formed a party that unified former Red Sticks with disillusioned American-allied Creeks like Big Warrior. The party crafted a petition to Secretary of War James Barbour that reiterated the National Council's position that the Creeks had no land left to sell and named Little Prince and Big Warrior as rightful leaders of the Creek National Council.

By the 1820s, Big Warrior delegated a majority of his formal headman duties to Opothle Yoholo to focus on cultivating peace amongst the Creek factions. In late 1824, Little Prince, Opothle Yoholo, and McIntosh appealed to U.S commissioners that ceding further lands would bring their "downfall and ruin."

As a leader of the Creek National Council, Big Warrior traveled to Washington D.C., to represent the Creeks against further white encroachment. He fell ill on the trip and died on March 8, 1825. After his death, Opothle Yoholo rose to prominence and strengthened his political leadership in the Creek National Council. Opothle Yoholo along with a handful of other Creek representatives worked with a delegation in Washington including the National Council's secretary, Cherokee John Ridge, which led to the Treaty of Creek Agency in 1827 that ceded all remaining Creek land in Georgia to the United States.

Further Reading

- Green, Michael D. The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1985.

- Griffith, Benjamin W., Jr. McIntosh and Weatherford: Creek Indian Leaders. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1988.

- Hudson, Angela Pulley. Creek Paths and Federal Roads: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves and the Making of the American South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Pearson, Joseph W. "Winter 1813: Blood on the Water." Alabama Heritage 107 (Winter 2013): 42-43.