Montgomery

Alabama State Capitol Building

Located in the heart of central Alabama, the city of Montgomery holds a strategic place in state, national, and international history. A frontier settlement, it became a center of the cotton kingdom, Alabama’s seat of government, and the original Confederate capital. Later, the 1886-87 Lightning Route electric trolley system and in 1910 the Wright Brothers’ civilian flying school brought it recognition as a center of technology. During the turbulent civil rights era, Montgomery citizens played a central role in some of its most important events, including the bus boycott and the Selma to Montgomery March. In 2019, the city elected its first African American mayor, Steven L. Reed, who also was the first black probate judge in Montgomery County. He is the son of the former longtime Alabama Education Association associate executive secretary and state Democratic Party official Joe L. Reed. Today, the city is the center of policy and economic development leading the state’s rise as a manufacturing and technology center.

Alabama State Capitol Building

Located in the heart of central Alabama, the city of Montgomery holds a strategic place in state, national, and international history. A frontier settlement, it became a center of the cotton kingdom, Alabama’s seat of government, and the original Confederate capital. Later, the 1886-87 Lightning Route electric trolley system and in 1910 the Wright Brothers’ civilian flying school brought it recognition as a center of technology. During the turbulent civil rights era, Montgomery citizens played a central role in some of its most important events, including the bus boycott and the Selma to Montgomery March. In 2019, the city elected its first African American mayor, Steven L. Reed, who also was the first black probate judge in Montgomery County. He is the son of the former longtime Alabama Education Association associate executive secretary and state Democratic Party official Joe L. Reed. Today, the city is the center of policy and economic development leading the state’s rise as a manufacturing and technology center.

Early History

Before the state of Alabama was even established, the site of present-day Montgomery was an important crossroads that straddled major Native American trade routes, with paths, streams, and the Alabama River connecting the Creek Indians to a wider world. Beginning in the sixteenth century, European intrusions began changing the destiny of the original inhabitants. By 1814, with the signing of the Treaty of Fort Jackson, the Creeks had ceded millions of acres, including what is now Montgomery County, to the United States.

Richard Montgomery

Settlers flooded the area, establishing numerous cotton plantations. With mechanization of textile production, the demand for cotton increased rapidly. The site again served as a crossroads for this emerging industry. In 1817 and 1818, three small settlements sprang up on the banks of the Alabama River, with two of these communities merging in 1819 to form the town of Montgomery, named for Gen. Richard Montgomery, a hero of the Revolutionary War. In 1822, the town became the seat of Montgomery County, itself named in 1816 for Maj. Lemuel Montgomery, an officer killed in the 1814 Battle of Horseshoe Bend.

Richard Montgomery

Settlers flooded the area, establishing numerous cotton plantations. With mechanization of textile production, the demand for cotton increased rapidly. The site again served as a crossroads for this emerging industry. In 1817 and 1818, three small settlements sprang up on the banks of the Alabama River, with two of these communities merging in 1819 to form the town of Montgomery, named for Gen. Richard Montgomery, a hero of the Revolutionary War. In 1822, the town became the seat of Montgomery County, itself named in 1816 for Maj. Lemuel Montgomery, an officer killed in the 1814 Battle of Horseshoe Bend.

As Alabama settlement expanded, the state legislature looked to relocate the capital from Tuscaloosa, in the west-central part of the state. Montgomery entrepreneur Andrew Dexter, for whom the city’s famed Dexter Avenue is named, was among its earliest promoters as the site of the new state capital. He had even reserved a portion of his property, known as “Goat Hill,” at the eastern end of Market Street for the location of the state house. In 1846, Montgomery won the long-sought prize when the legislature chose it as the capital city. One of the major points in the town’s favor was the Creek land cession that pushed the boundary of Alabama eastward to the Chattahoochee River, thus placing Montgomery quite close to the state’s geographic center. Other significant factors included the developing railroads, the free land (Goat Hill), and the funds that the city would raise through a bond issue to finance the construction of the state house. Completed in 1847, the Greek Revival edifice burned to the ground in December 1849. Undaunted, the state funded another building, completed in 1851, that still serves as the capitol today. That same year, the Montgomery & West Point Railroad connected Montgomery with terminals in Georgia, opening central Alabama to the Northeast and Midwest.

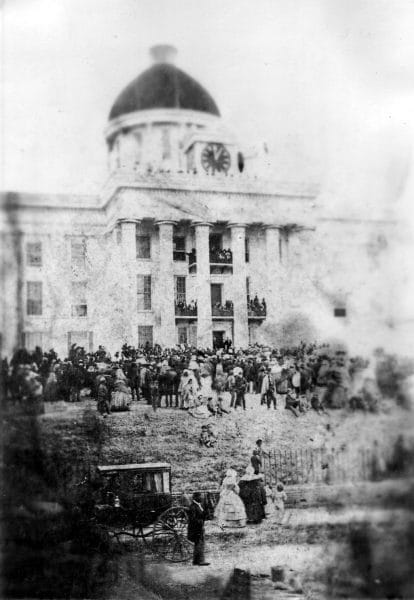

Inauguration of Jefferson Davis

The population of the city grew rapidly in the decades after its founding. By 1850, more than 12,000 people lived in the town, which had expanded to include several hotels, taverns, storehouses, and a cotton warehouse to accommodate the developing cotton trade along the riverfront. The 1850s in Montgomery were marked by prosperity and progress, and the town grew in sophistication. Signs of the trouble to come appeared, however, as the secession crisis began to heat up. Conflict grew among the secessionists, led by firebrand legislator William Lowndes Yancey, those who vehemently opposed secession, and a substantial moderate element. In the presidential campaign of 1860, Yancey failed to achieve his demands for southern rights at the Democratic Convention and led the southern delegates out, fracturing the national Democratic Party and assuring the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln. The southern states seceded soon thereafter, and Montgomery hosted the constitutional convention for the new Confederate States of America and was selected as the provisional capital. Montgomery served in that capacity for three months until May 1861, when it lost that honor to Richmond, Virginia.

Inauguration of Jefferson Davis

The population of the city grew rapidly in the decades after its founding. By 1850, more than 12,000 people lived in the town, which had expanded to include several hotels, taverns, storehouses, and a cotton warehouse to accommodate the developing cotton trade along the riverfront. The 1850s in Montgomery were marked by prosperity and progress, and the town grew in sophistication. Signs of the trouble to come appeared, however, as the secession crisis began to heat up. Conflict grew among the secessionists, led by firebrand legislator William Lowndes Yancey, those who vehemently opposed secession, and a substantial moderate element. In the presidential campaign of 1860, Yancey failed to achieve his demands for southern rights at the Democratic Convention and led the southern delegates out, fracturing the national Democratic Party and assuring the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln. The southern states seceded soon thereafter, and Montgomery hosted the constitutional convention for the new Confederate States of America and was selected as the provisional capital. Montgomery served in that capacity for three months until May 1861, when it lost that honor to Richmond, Virginia.

During the war, Montgomery remained largely on the sidelines of the actual fighting, instead supplying men and materials to the war effort. The city housed six hospitals and several homes that provided medical services to the sick and wounded. Montgomery was largely untouched by war until April 1865, when federal forces under Gen. James H. Wilson began moving toward the city. The scant Confederate units moved out, but before departing, military and municipal leaders decided to burn some 100,000 bales of cotton stored in local warehouses. The acrid smell of burning cotton greeted Union troops as they entered town in the early morning of April 12, 1865. During their two-day occupation, they destroyed the arsenal, train depot, foundries, rolling mills, nitre works, several riverboats, and railway cars.

Montgomery, having suffered little physical damage, saw drastic changes in its social, political, and economic life as freed blacks took positions on the city council and Republican mayors guided the city through the turbulent times of Reconstruction. The free black population built churches and organized educational, civic, and social institutions. These advances began to reverse in 1875, when the Democrats regained control of the state and city governments and imposed white supremacy, although black political influence continued for some time.

Modernization

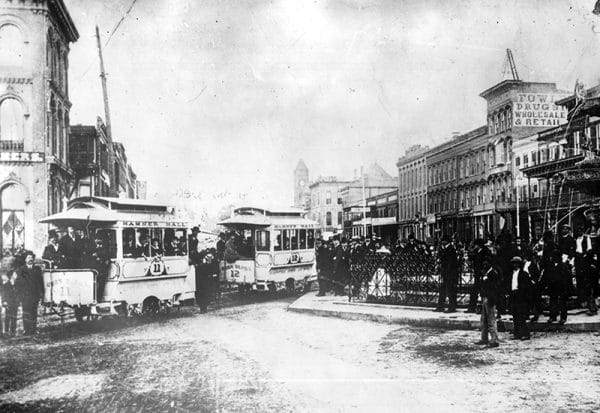

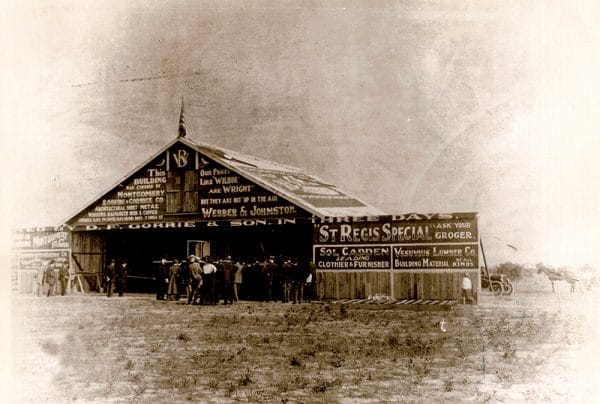

Montgomery, ca. 1885

By the 1880s, Montgomery had wholeheartedly embraced new technology and ushered in an era of modernization. In 1886, the city gained fame as the home of the very first electric streetcar system in the Western Hemisphere. A major railroad hub for Central Alabama and its river traffic, Montgomery became the wholesale district for the region. By now a city of more than 17,000, the city boasted cotton brokerages, warehouses, large commercial banks, metal manufacturing, dry goods industries, lumbering, textile mills, and breweries.

Montgomery, ca. 1885

By the 1880s, Montgomery had wholeheartedly embraced new technology and ushered in an era of modernization. In 1886, the city gained fame as the home of the very first electric streetcar system in the Western Hemisphere. A major railroad hub for Central Alabama and its river traffic, Montgomery became the wholesale district for the region. By now a city of more than 17,000, the city boasted cotton brokerages, warehouses, large commercial banks, metal manufacturing, dry goods industries, lumbering, textile mills, and breweries.

In 1896, the Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy vs. Ferguson established rules for “separate but equal” facilities in rail travel and set in motion drastic societal changes for people in the South. In Alabama, white elites quickly moved to take advantage of the new opportunities for curbing black and poor white political involvement and entrenched existing Jim Crow laws. In 1901, the legislature in Montgomery rewrote the state constitution, which disfranchised blacks and many whites, as the Plessy verdict resonated across the South. Montgomery municipal leaders hastened to pass ordinances designed to separate blacks and whites on trolleys, leading blacks to boycott the trolleys in 1901 and stage a trolley strike in 1906. The outcome was segregated seating on trolleys and, later, on city buses. By then, however, transportation was moving in another direction: upward.

Wright Brothers Flying School

In 1910, the Commercial Men’s Association ignited an interest in flying when it invited the Wright brothers to Montgomery, where the inventors operated the first civilian flying school for three months on the Kohn Plantation west of town. This event was the first of many associations with flight for the city. During World War I, the same land served as Ardmont, a repair depot for Army aircraft, including those from Taylor Field, east of Montgomery. At the same time, infantry troops received training at Camp Sheridan; writer F. Scott Fitzgerald met his future wife, Zelda Sayre, while stationed there. Following the war, Ardmont remained active and, renamed as Maxwell Field, trained hundreds of flyers during World War II. Now Maxwell Air Force Base, today it is the home of the Air University, the advanced educational center for Air Force officers, as well as several other facilities. Between 1940 and 1950, the population increased from 78,000 to 106,000. Many residents lived in the expanding neighborhoods of Cottage Hill, Cloverdale, and the Garden District.

Wright Brothers Flying School

In 1910, the Commercial Men’s Association ignited an interest in flying when it invited the Wright brothers to Montgomery, where the inventors operated the first civilian flying school for three months on the Kohn Plantation west of town. This event was the first of many associations with flight for the city. During World War I, the same land served as Ardmont, a repair depot for Army aircraft, including those from Taylor Field, east of Montgomery. At the same time, infantry troops received training at Camp Sheridan; writer F. Scott Fitzgerald met his future wife, Zelda Sayre, while stationed there. Following the war, Ardmont remained active and, renamed as Maxwell Field, trained hundreds of flyers during World War II. Now Maxwell Air Force Base, today it is the home of the Air University, the advanced educational center for Air Force officers, as well as several other facilities. Between 1940 and 1950, the population increased from 78,000 to 106,000. Many residents lived in the expanding neighborhoods of Cottage Hill, Cloverdale, and the Garden District.

Civil Rights

Selma to Montgomery March End

When black servicemen returned from fighting fascism and imperialism in World War II, they found that their freedoms were still restricted by segregation, just as they had been for decades. Most public places were segregated, and blacks were relegated to the back of the bus on the city’s public transportation. Efforts to make the system more equitable failed, but Rosa Parks‘s arrest for refusing to give her seat to a white man on December 1, 1955, brought startling change. The event sparked a year-long boycott that in turn sparked larger demonstrations, spearheaded by Montgomery religious and civic leaders Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King Jr., and E. D. Nixon, throughout the state for equal justice for blacks. The state capitol served as the culminating point for the Selma to Montgomery March for voting rights in the spring of 1965, and King made one of his greatest speeches there to an estimated 25,000 people. The 1965 Voting Rights Act made a significant impact that paved the way for black registration and participation in the world of politics and government.

Selma to Montgomery March End

When black servicemen returned from fighting fascism and imperialism in World War II, they found that their freedoms were still restricted by segregation, just as they had been for decades. Most public places were segregated, and blacks were relegated to the back of the bus on the city’s public transportation. Efforts to make the system more equitable failed, but Rosa Parks‘s arrest for refusing to give her seat to a white man on December 1, 1955, brought startling change. The event sparked a year-long boycott that in turn sparked larger demonstrations, spearheaded by Montgomery religious and civic leaders Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King Jr., and E. D. Nixon, throughout the state for equal justice for blacks. The state capitol served as the culminating point for the Selma to Montgomery March for voting rights in the spring of 1965, and King made one of his greatest speeches there to an estimated 25,000 people. The 1965 Voting Rights Act made a significant impact that paved the way for black registration and participation in the world of politics and government.

Hyundai Paint Shop in Montgomery

Montgomery owes much to its role as the seat of Alabama government, with the ever-expanding state bureaucracy and other government jobs providing employment to 22.5 percent of the work force in 2016. Maxwell Air Force Base’s Air University employs several thousand people and in all sectors pours more than $1 billion a year into the local economy. Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama built a factory in Montgomery in 2002 and began full-scale automobile production three years later, and suppliers who manufacture and furnish parts to Hyundai have added to the numbers of employed as well. Tourism and entertainment provide direct employment for more than 8,000, with another 4,000 in related jobs.

Hyundai Paint Shop in Montgomery

Montgomery owes much to its role as the seat of Alabama government, with the ever-expanding state bureaucracy and other government jobs providing employment to 22.5 percent of the work force in 2016. Maxwell Air Force Base’s Air University employs several thousand people and in all sectors pours more than $1 billion a year into the local economy. Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama built a factory in Montgomery in 2002 and began full-scale automobile production three years later, and suppliers who manufacture and furnish parts to Hyundai have added to the numbers of employed as well. Tourism and entertainment provide direct employment for more than 8,000, with another 4,000 in related jobs.

Demographics

According to 2020 Census estimates, Montgomery recorded a population of 199,054. Of that number, 60.8 percent identified themselves as African American, 31.5 percent as white, 3.8 percent as Hispanic, 2.9 percent as two or more races, 3.2 percent as Asian, and 0.2 as American Indian. The city’s median household income was $49,608, and per capita income was $28,720.

Employment

According to 2020 Census estimates, the workforce in Montgomery was divided among the following industrial categories:

- Educational services, and health care and social assistance (23.1 percent)

- Manufacturing (11.3 percent)

- Retail trade (11.1 percent)

- Professional, scientific, management, and administrative and waste management services (10.8 percent)

- Public administration (10.5 percent)

- Arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation, and food services (10.2 percent)

- Finance, insurance, and real estate, rental, and leasing (5.5 percent)

- Other services, except public administration (5.2 percent)

- Transportation and warehousing and utilities (4.9 percent)

- Construction (3.8 percent)

- Wholesale trade (2.2 percent)

- Information (1.2 percent)

- Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, and extractive (0.3 percent)

Education

Montgomery is a center of education in the state of Alabama. It is home to campuses of both Auburn University and Troy University as well as religiously affiliated Faulkner University and Huntingdon College, and Alabama State University, the state’s oldest historically black college. Maxwell Air Force Base’s Air University is the highest academic branch of the U.S. Air Force. Trenholm State Technical College and a branch of South University offer technical and business related degrees. The city is home to numerous public, private, and church related elementary and secondary schools.

Events and Places of Interest

Alabama Department of Archives and History

The city of Montgomery is home to a large number of historic structures, museums, and monuments. The capitol grounds and building are open to visitors, and are home to the Confederate Monument as well as other statues and monuments to important historical figures, including civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and politician Lister Hill. Adjacent are the First White House of the Confederacy, the Alabama Department of Archives and History, and Bicentennial Park, dedicated on December 14, 2019, in honor of the state’s 200th birthday. Also located near the capitol are the offices of the Southern Poverty Law Center and the associated Civil Rights Memorial and Memorial Center commemorating people who lost their lives during the civil rights movement. Other sites connected with the civil rights movement include the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, the Dexter Parsonage Museum, Freedom Rides Museum, the Troy University Rosa Parks Museum, and the City of St. Jude Interpretive Center and Garden.

Alabama Department of Archives and History

The city of Montgomery is home to a large number of historic structures, museums, and monuments. The capitol grounds and building are open to visitors, and are home to the Confederate Monument as well as other statues and monuments to important historical figures, including civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and politician Lister Hill. Adjacent are the First White House of the Confederacy, the Alabama Department of Archives and History, and Bicentennial Park, dedicated on December 14, 2019, in honor of the state’s 200th birthday. Also located near the capitol are the offices of the Southern Poverty Law Center and the associated Civil Rights Memorial and Memorial Center commemorating people who lost their lives during the civil rights movement. Other sites connected with the civil rights movement include the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, the Dexter Parsonage Museum, Freedom Rides Museum, the Troy University Rosa Parks Museum, and the City of St. Jude Interpretive Center and Garden.

Other attractions include the living-history museum Old Alabama Town, the Hank Williams Museum, and the Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum, the W. A. Gayle Planetarium, and the Montgomery Zoo. Located on the eastern edge of the city are the Alabama Shakespeare Festival and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, both located within the Wynton M. Blount Cultural Park. In 2023, the city opened the Montgomery Whitewater Park, a 120-acre complex featuring a manmade whitewater channel for rafting, kayaking, and canoeing. The park also offers visitors zip lines and climbing structures, hiking and mountain biking trails, live entertainment facilities, and shopping and dining areas.

Further Reading

- Blue, M. P. A Brief History of Montgomery. Montgomery, Ala.: T. C. Bingham & Co., 1878.

- Williams, Clanton W. The Early History of Montgomery and Incidentally of the State of Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

External Links

- City of Montgomery

- Montgomery City-County Public Library

- Montgomery Area Chamber of Commerce

- Montgomery County Historical Society

- Encycylopedia of Southern Jewish Communities

- National Register of Historic Places: Montgomery County

- Alabama Department of Archives and History

- Alabama Legacy Moments: Confederacy Government in Montgomery

- Alabama Legacy Moments: Montgomery State Capitol

- Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts

- Old Alabama Town

- Alabama Center for Traditional Culture

- Southern Literary Trail

- Alabama Folklife Association

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Montgomery Zoo

- Troy University Rosa Parks Museum

- Hank Williams Museum

- Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church

- MOOseum

- Auburn University at Montgomery

- Alabama State University

- Troy University Montgomery Campus

- Faulkner University

- Huntingdon College

- South University in Montgomery

- Trenholm State Technical College

- Montgomery Biscuits

- Montgomery Advertiser