Lowndes County Freedom Organization

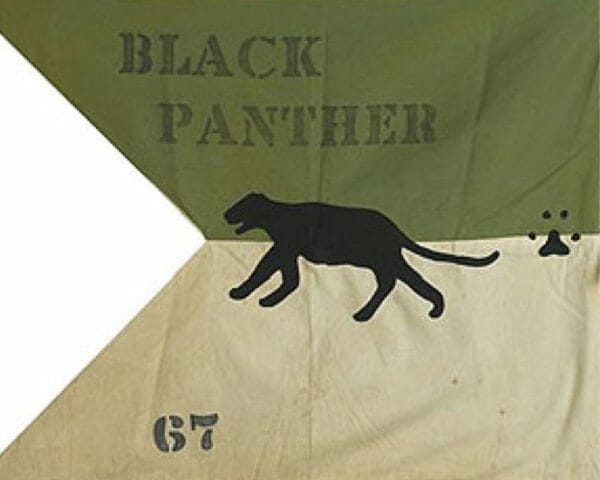

Black Panther Logo

The Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), or Black Panther Party, was a short-lived political party that formed in 1966 to represent African Americans in the central Alabama Black Belt counties. Though the organization failed to win any election, its influence was felt far beyond Alabama by providing the foundation for the better-known Black Panther Party for Self-Defense that arose in Oakland, California. Known for years as “Bloody Lowndes,” the county had a well-deserved reputation for brutality and entrenched racism. Although the population was roughly 80 percent African American, no black resident had successfully registered to vote in more than 60 years, as the county was controlled by 86 white families who owned 90 percent of the land.

Black Panther Logo

The Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), or Black Panther Party, was a short-lived political party that formed in 1966 to represent African Americans in the central Alabama Black Belt counties. Though the organization failed to win any election, its influence was felt far beyond Alabama by providing the foundation for the better-known Black Panther Party for Self-Defense that arose in Oakland, California. Known for years as “Bloody Lowndes,” the county had a well-deserved reputation for brutality and entrenched racism. Although the population was roughly 80 percent African American, no black resident had successfully registered to vote in more than 60 years, as the county was controlled by 86 white families who owned 90 percent of the land.

Stokely Carmichael, an organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and who had recently coined the phrase “Black Power,” was dispatched to Lowndes County to register voters in the summer of 1965. SNCC members were losing faith in the nonviolent approach taken by other civil rights organizations, namely the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and Carmichael found Lowndes’ rural black population armed and willing to defend itself. Carmichael and other organizers, however, were able to register only about 250 African American voters by August 1965, each of whom were required to pass a literacy test. After the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited such measures to determine eligibility and provided enforcement provisions, the number of black voters increased, but so did white resistance and intimidation.

John Hulett

Carmichael was not the only one growing impatient that year. Local activist John Hulett, a founder and leader of the Lowndes County Christian Movement for Human Rights, began seeking assistance from SNCC after being repeatedly refused help by the SCLC. Carmichael and other SNCC volunteers joined with Hulett’s fledgling organization, which was also trying to register black voters. The two groups redoubled their efforts following the murder of Jonathan Myrick Daniels, a white Episcopal seminarian and SNCC volunteer, on August 20. Given the extent of white resistance, however, group leaders doubted the effectiveness of trying to register blacks for the white-controlled Democratic Party. Instead, they formed a new, independent party at the county level, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, and attempted to register as many black voters as possible. Hulett served as the LCFO’s first chairman.

John Hulett

Carmichael was not the only one growing impatient that year. Local activist John Hulett, a founder and leader of the Lowndes County Christian Movement for Human Rights, began seeking assistance from SNCC after being repeatedly refused help by the SCLC. Carmichael and other SNCC volunteers joined with Hulett’s fledgling organization, which was also trying to register black voters. The two groups redoubled their efforts following the murder of Jonathan Myrick Daniels, a white Episcopal seminarian and SNCC volunteer, on August 20. Given the extent of white resistance, however, group leaders doubted the effectiveness of trying to register blacks for the white-controlled Democratic Party. Instead, they formed a new, independent party at the county level, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, and attempted to register as many black voters as possible. Hulett served as the LCFO’s first chairman.

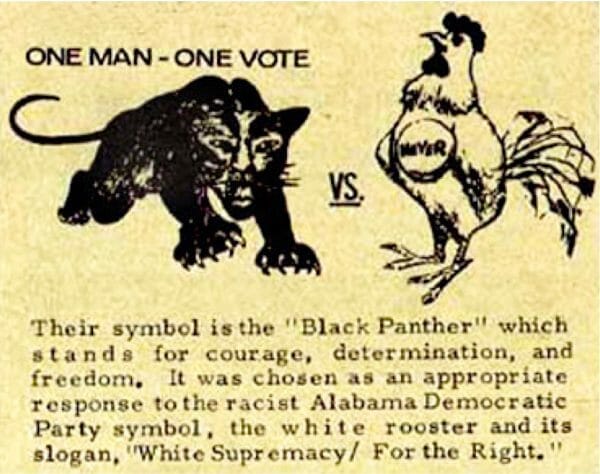

Alabama election laws required political parties to have an emblem, so the new party chose a crouching black panther. Hulett explained that like a panther, Lowndes County African Americans had been pushed back into a corner and would come out “fighting for life or death.” The emblem was seized on by the media, and LCFO also came to be known as the Black Panther Party. Although the organization was, in theory, open to anyone, it became a de facto all-black organization, as no white voters wanted to join.

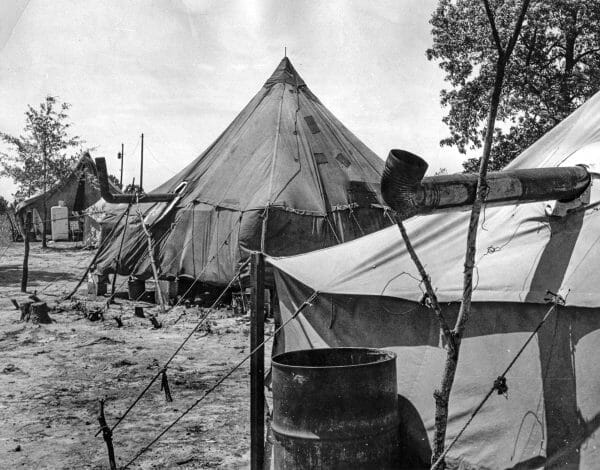

Lowndes County Freedom Organization Headquarters

The new party hoped to get enough people to vote in the upcoming 1966 election that African Americans might be elected to office and assist the county’s impoverished black population. SNCC had always focused on education as a means of securing civil rights, and the LCFO followed suit. It organized political education classes and registration drives and published a booklet that informed citizens of the potential problems they could face if they registered. The LCFO experienced constant criticism from the Democratic Party, as well as the SCLC, which felt that blacks should vote in the Democratic primary. The recent decision of the Democratic Party to increase its filing fee for candidates to $500 solidified the activists’ resolve to form a completely new party, regardless of the criticism.

Lowndes County Freedom Organization Headquarters

The new party hoped to get enough people to vote in the upcoming 1966 election that African Americans might be elected to office and assist the county’s impoverished black population. SNCC had always focused on education as a means of securing civil rights, and the LCFO followed suit. It organized political education classes and registration drives and published a booklet that informed citizens of the potential problems they could face if they registered. The LCFO experienced constant criticism from the Democratic Party, as well as the SCLC, which felt that blacks should vote in the Democratic primary. The recent decision of the Democratic Party to increase its filing fee for candidates to $500 solidified the activists’ resolve to form a completely new party, regardless of the criticism.

After much effort, more blacks were registered to vote than whites. The majority of these new voters, however, were sharecroppers, and they faced hostile responses from land-owning whites through evictions that left them homeless and unemployed. SNCC and LCFO leaders organized a “tent city” to house the displaced sharecroppers and helped them find new work and homes.

Stokely Carmichael Released from Jail

In May 1966, the party held its primary, with seven candidates vying for sheriff, coroner, tax assessor, and the board of education. Though both SNCC and LCFO continued to win the support of Lowndes County African Americans, the new party could not overcome the deeply entrenched racism of “Bloody Lowndes.” Each of the seven candidates lost in the general election in November of 1966, and many African Americans believed it resulted from plantation owners pressuring their black sharecroppers to vote for white candidates or not at all. After the election, SNCC organizers, including Carmichael, who went on to lead SNCC in 1966, gradually drifted out of Lowndes County. In 1970, the LCFO merged with the statewide Democratic Party, and former LCFO candidates won their first offices in the county. In that election, four years after the LCFO’s defeat, John Hulett was elected sheriff of Lowndes County, a position he would hold for 22 years, before serving three terms as probate judge of Lowndes County.

Stokely Carmichael Released from Jail

In May 1966, the party held its primary, with seven candidates vying for sheriff, coroner, tax assessor, and the board of education. Though both SNCC and LCFO continued to win the support of Lowndes County African Americans, the new party could not overcome the deeply entrenched racism of “Bloody Lowndes.” Each of the seven candidates lost in the general election in November of 1966, and many African Americans believed it resulted from plantation owners pressuring their black sharecroppers to vote for white candidates or not at all. After the election, SNCC organizers, including Carmichael, who went on to lead SNCC in 1966, gradually drifted out of Lowndes County. In 1970, the LCFO merged with the statewide Democratic Party, and former LCFO candidates won their first offices in the county. In that election, four years after the LCFO’s defeat, John Hulett was elected sheriff of Lowndes County, a position he would hold for 22 years, before serving three terms as probate judge of Lowndes County.

The spirit of the LCFO endured despite its defeat. Similar “freedom organizations” appeared across the country. The party’s slogan of “Black Power” also spread throughout the nation, and its black panther emblem was adopted by activists Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, a SNCC veteran in the Lowndes County effort, who together organized the Oakland-based Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1966. There was no formal relationship between the LCFO and the later organization, and Hulett and others resented the use of their symbol to represent an organization that encouraged the use of violence. The latter organization became much more well-known than the LCFO for its openly militant rhetoric, but its foundation was the LCFO’s principles of self-empowerment and grass-roots activism.

Video

Further Reading

- Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Cobb, Charles E. Jr. On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Movement. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Algonquin Books, 2008.

- Cammeron, Dwight B., and Richard Adams. The Lowndes County Freedom Organization. VHS video. Produced by the University of Alabama Center for Public Television and Radio. Princeton, N.J.: Films for the Humanities & Sciences, 1995.

- Gaillard, Frye. Cradle of Freedom: Alabama and the Movement that Changed America. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Jeffries, Hasan K. Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt. New York: NYU Press, 2009.