Voting Rights Act of 1965 in Alabama

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) was an effort by the U.S. Congress to outlaw voting regulations and procedures in Alabama and other states, principally in the South, that served to deny voting rights to African Americans. Its passage was prompted by the first aborted Selma-to-Montgomery march on March 15, 1965, that ended with the assault on marchers and came to be known as "Bloody Sunday." Although every member of Alabama's congressional delegation voted against the measure, it was overwhelmingly passed by Congress and signed into law by Pres. Lyndon Johnson on August 6, 1965. The law led to a surge in African American voting and office holding in Alabama and the rest of the South.

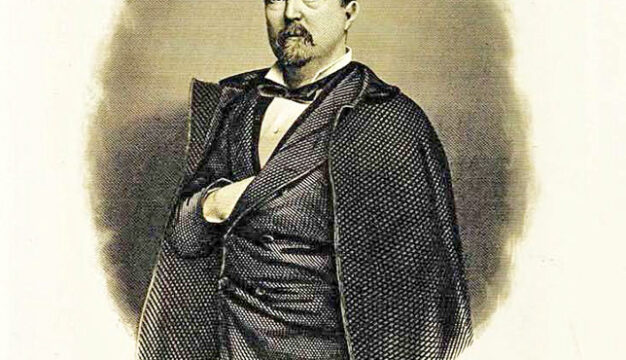

Benjamin S. Turner

Suffrage for newly freed African American men in Alabama was guaranteed under Alabama's 1868 Reconstruction Constitution and the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which was passed during the period of Congressional Reconstruction. Nearly 170 African American men were elected to state office in the Reconstruction era, and three—Jeremiah Haralson, James T. Rapier, and Benjamin S. Turner—were elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. In response, so-called "Redeemer" Democrats began to curtail voting rights by gerrymandering voting districts to benefit Democratic white candidates, instituting strict residency requirements, and using intimidation, fraud, and outright violence at polling places, often at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan, to prevent blacks and Republicans from voting. (So thoroughly demolished were the Republicans in the 1874 elections, wrote one Alabama historian, that Democrats would go unchallenged until the late twentieth century.) Then, in 1893, the state passed the Sayre Act, which required ballots to list candidates alphabetically rather than by party to confuse voters and required voters to register with election officials in May to make voting difficult for farmers. Even so, by 1900, more than 180,000 eligible African American men were registered to vote.

Benjamin S. Turner

Suffrage for newly freed African American men in Alabama was guaranteed under Alabama's 1868 Reconstruction Constitution and the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which was passed during the period of Congressional Reconstruction. Nearly 170 African American men were elected to state office in the Reconstruction era, and three—Jeremiah Haralson, James T. Rapier, and Benjamin S. Turner—were elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. In response, so-called "Redeemer" Democrats began to curtail voting rights by gerrymandering voting districts to benefit Democratic white candidates, instituting strict residency requirements, and using intimidation, fraud, and outright violence at polling places, often at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan, to prevent blacks and Republicans from voting. (So thoroughly demolished were the Republicans in the 1874 elections, wrote one Alabama historian, that Democrats would go unchallenged until the late twentieth century.) Then, in 1893, the state passed the Sayre Act, which required ballots to list candidates alphabetically rather than by party to confuse voters and required voters to register with election officials in May to make voting difficult for farmers. Even so, by 1900, more than 180,000 eligible African American men were registered to vote.

The following year though, however, Alabama lawmakers signed into law a new constitution that included numerous rules and policies intended to disenfranchise black and poor white voters. Such methods consisted of employment, literacy, and property qualifications and a grandfather clause that exempted from the qualifications men whose ancestors who had served in the military as far back as the American Revolution. It also disqualified voters for numerous criminal convictions as well as for a variety of "moral failings." This newly imposed racially based disenfranchisement also rested on compliant boards of registrars appointed by a committee of state government officials including the governor. The registrars were relied upon to use their discretion when judging qualifications to fail eligible African American applicants but approve white conservative Democratic applicants. By 1903, fewer than 3,000 African Americans could vote in the state, and those seeking suffrage rights again faced intimidation and threats of job loss and eviction. The Constitution was harmful to white men as well, though less so, disenfranchising some 41,000 out of 232,000 registered white voters.

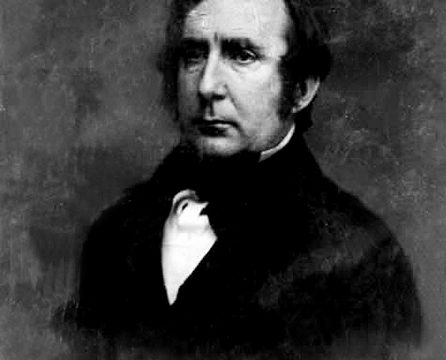

Voter Registration in Mobile

The Democratic Party held whites-only primaries from 1902 until 1944, when they were outlawed by the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Smith v. Allwright. In 1946, Alabama responded with the Boswell Amendment, which authorized the governor to appoint local election officials and required voting applicants to understand and explain a section of the U.S. Constitution to the satisfaction of county registrars. It was declared unconstitutional in 1949. The state then turned to boards of registrars to institute a uniform questionnaire on basic employment and criminal history and civics. Minor and insignificant errors, though, were used to deny applicants. In 1951, the state required that applicants be able to read and write in English any article of the U.S. Constitution given by the board of registrars. It would remain in force until the VRA was enacted in 1965. A "moral character" requirement was also instituted, in which applicants needed two registered voters to personally vouch for the applicant. However, there were too few, or no blacks registered, depending on the county, and few whites would vouch for blacks. Failed applicants could appeal, but there were too few African American lawyers willing to handle the cases.

Voter Registration in Mobile

The Democratic Party held whites-only primaries from 1902 until 1944, when they were outlawed by the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Smith v. Allwright. In 1946, Alabama responded with the Boswell Amendment, which authorized the governor to appoint local election officials and required voting applicants to understand and explain a section of the U.S. Constitution to the satisfaction of county registrars. It was declared unconstitutional in 1949. The state then turned to boards of registrars to institute a uniform questionnaire on basic employment and criminal history and civics. Minor and insignificant errors, though, were used to deny applicants. In 1951, the state required that applicants be able to read and write in English any article of the U.S. Constitution given by the board of registrars. It would remain in force until the VRA was enacted in 1965. A "moral character" requirement was also instituted, in which applicants needed two registered voters to personally vouch for the applicant. However, there were too few, or no blacks registered, depending on the county, and few whites would vouch for blacks. Failed applicants could appeal, but there were too few African American lawyers willing to handle the cases.

In 1964, just prior to passage of the VRA, only Mississippi had a smaller percentage of eligible African Americans registered to vote than Alabama, 6.7 percent compared to 23.0 percent, though some sources say Alabama had less than that. The overrepresentation of white voters in rural counties and state legislatures had national significance, placing political control in the hands of a small and often reactionary oligarchy, according to prominent historians of the South.

Federal Efforts to Strengthen Voting Rights

Pres. Eisenhower Signs Voting Rights Act of 1957

As voting rights activists fought in the courts and the modern civil rights movement gained momentum in the 1950s, the federal government tried to strengthen voting rights with the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and additional legislation in 1960 and 1964. Despite including provisions to guarantee voting rights, the measures had little immediate effect. The 1957 Act authorized the U.S. Attorney General to bring suit on behalf of minority groups that faced discrimination or harassment while attempting to vote. The Acts in 1960 and 1964 strengthened the language in the 1957 Act but overall had a limited direct impact in that regard. Also in 1960, the Supreme Court addressed literacy tests in Macon County in United States v. Alabama. Later that year, the high court declared unconstitutional the manner in which white city officials in Tuskegee, Macon County, had drawn the city's boundaries to remove most of its African American voters to ensure electoral victories for white candidates. In 1961, the Middle District Court in Alabama declared numerous means implemented by Macon County registrars to deny local African Americans voting rights unconstitutional with regard to the 1957 Civil Rights Act. The 1957 and 1960 Acts, though, gave federal officials the power to subpoena registrar records and led federal authorities to petition for injunctions against discriminatory policies and new questionnaires and filed suits against boards to prohibit discrimination. Yet efforts to deter voting continued. In 1962, for example, the Dallas County Board of Education terminated 36 teachers who had given testimony against the board of registrars.

Pres. Eisenhower Signs Voting Rights Act of 1957

As voting rights activists fought in the courts and the modern civil rights movement gained momentum in the 1950s, the federal government tried to strengthen voting rights with the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and additional legislation in 1960 and 1964. Despite including provisions to guarantee voting rights, the measures had little immediate effect. The 1957 Act authorized the U.S. Attorney General to bring suit on behalf of minority groups that faced discrimination or harassment while attempting to vote. The Acts in 1960 and 1964 strengthened the language in the 1957 Act but overall had a limited direct impact in that regard. Also in 1960, the Supreme Court addressed literacy tests in Macon County in United States v. Alabama. Later that year, the high court declared unconstitutional the manner in which white city officials in Tuskegee, Macon County, had drawn the city's boundaries to remove most of its African American voters to ensure electoral victories for white candidates. In 1961, the Middle District Court in Alabama declared numerous means implemented by Macon County registrars to deny local African Americans voting rights unconstitutional with regard to the 1957 Civil Rights Act. The 1957 and 1960 Acts, though, gave federal officials the power to subpoena registrar records and led federal authorities to petition for injunctions against discriminatory policies and new questionnaires and filed suits against boards to prohibit discrimination. Yet efforts to deter voting continued. In 1962, for example, the Dallas County Board of Education terminated 36 teachers who had given testimony against the board of registrars.

In 1962, the 24th Amendment outlawing the poll tax was proposed to the states and was ratified on January 23, 1964, after South Dakota's passage. (Alabama, one of five states that imposed such a tax, along with Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia, did not ratify the amendment until April 11, 2002.) Later in 1964, the Supreme Court addressed malapportioned legislative districts in the landmark Alabama-based Reynolds v. Sims case. In 1966, The U.S. Supreme Court declared poll taxes unconstitutional in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, and the Middle District Court of Alabama declared the poll tax in Alabama unconstitutional in United States v. Alabama.

Pres. Lyndon Johnson and Martin Luther King Jr.

After voting rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson died on February 26, 1965, from a gunshot wound by a white man, the Rev. James Bevel of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) called for a march from Selma, Dallas County, to Montgomery, Montgomery County, to protest for voting reforms. The ensuing March 7, 1965, march ended with violence and became known as "Bloody Sunday" for the ferocious reaction of law enforcement officials. Many historians credit this tragedy with Pres. Lyndon Johnson's subsequent proposal of reforms outlined in a speech to a televised joint session of Congress on March 15. Likewise, some point to the murder of activist Viola Liuzzo on March 12 in Lowndes County as also prompting more federal action. Regardless, Johnson had been looking to remove barriers to African American participation not long after the 1964 presidential election.

Pres. Lyndon Johnson and Martin Luther King Jr.

After voting rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson died on February 26, 1965, from a gunshot wound by a white man, the Rev. James Bevel of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) called for a march from Selma, Dallas County, to Montgomery, Montgomery County, to protest for voting reforms. The ensuing March 7, 1965, march ended with violence and became known as "Bloody Sunday" for the ferocious reaction of law enforcement officials. Many historians credit this tragedy with Pres. Lyndon Johnson's subsequent proposal of reforms outlined in a speech to a televised joint session of Congress on March 15. Likewise, some point to the murder of activist Viola Liuzzo on March 12 in Lowndes County as also prompting more federal action. Regardless, Johnson had been looking to remove barriers to African American participation not long after the 1964 presidential election.

The VRA Passes

The Johnson Administration proposal was introduced in the House on March 17 and in the Senate on March 18. The Senate passed a version on May 26, 1965, by a 77-19 vote and the House of Representatives followed on July 9 by a 333-85 vote. A conference report that aligned the two versions was passed by similar tallies on August 3 in the House and on August 4 in the Senate. Johnson signed the act into law on August 6. Both of Alabama's U.S. senators, Lister Hill and John Sparkman, voted against it, as did all eight members of the Alabama delegation to the U.S. House of Representatives. Legislators from Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia voted against it as well.

Pres. Lyndon Johnson Signs Voting Rights Act of 1965

At the time of passage, the law consisted of 19 sections. (It has since been amended in 1970, 1975, 1982, 1992, and 2006.) Most notably, section 2 prohibits states and political subdivisions from imposing voting qualification laws to deny citizens the right to vote on account of race or skin color. Section 3 authorizes the appointment of federal voting examiners. Section 4 ensures that no citizen shall be denied the right to vote because of a failure to comply with any "test or device," such as having to demonstrate the ability to read, write, understand, or interpret any matter; demonstrate any educational achievement and knowledge of any particular subject; possess good moral character; or prove qualification by the voucher of registered voters or members of any other class. It also included special temporary provisions that applied to areas in which there was a history of voting rights abuses, including Alabama. Section 5 established an oversight apparatus requiring that new voting laws in covered states and jurisdictions be approved in advance. Known as the "preclearance provision," it was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1966 case South Carolina v. Katzenbach but later successfully challenged in the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder Supreme Court case that overturned a portion of section 4 as unconstitutional. Provisions 6, 7, and 8 gave the U.S. Attorney General the authority to appoint voting examiners and assign federal officials to observe voting processes in jurisdictions covered under Section 4.

Pres. Lyndon Johnson Signs Voting Rights Act of 1965

At the time of passage, the law consisted of 19 sections. (It has since been amended in 1970, 1975, 1982, 1992, and 2006.) Most notably, section 2 prohibits states and political subdivisions from imposing voting qualification laws to deny citizens the right to vote on account of race or skin color. Section 3 authorizes the appointment of federal voting examiners. Section 4 ensures that no citizen shall be denied the right to vote because of a failure to comply with any "test or device," such as having to demonstrate the ability to read, write, understand, or interpret any matter; demonstrate any educational achievement and knowledge of any particular subject; possess good moral character; or prove qualification by the voucher of registered voters or members of any other class. It also included special temporary provisions that applied to areas in which there was a history of voting rights abuses, including Alabama. Section 5 established an oversight apparatus requiring that new voting laws in covered states and jurisdictions be approved in advance. Known as the "preclearance provision," it was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1966 case South Carolina v. Katzenbach but later successfully challenged in the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder Supreme Court case that overturned a portion of section 4 as unconstitutional. Provisions 6, 7, and 8 gave the U.S. Attorney General the authority to appoint voting examiners and assign federal officials to observe voting processes in jurisdictions covered under Section 4.

Results in Alabama

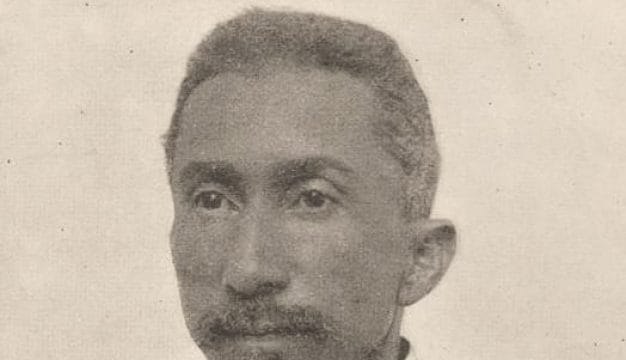

Lowndes County Voters

Within two years after passage, more than half of eligible African Americans in Alabama (51.2 percent) had registered to vote, rising from fewer than 93,000 to more than 248,000, according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. The law suspended the use of questionnaires and imposed federal officials and election examiners to oversee the registration process, which had been formerly controlled by local boards of registrars who actively impeded black registrants. Some 60,000 individuals were aided by these officials. That number included more than 19,000 voters in Jefferson County and 9,000 in Montgomery County. In Dallas County, where only 320 out of more than 15,000 eligible African American voters had been registered, nearly 9,000 were signed up to vote. In 1964, in Lowndes and Wilcox Counties, there were no African Americans registered to vote, but 59.1 percent and 62.1 percent had been registered, respectively, by 1967. These strides prompted Gov. George Wallace to mobilize more white Alabamians to register as well, from more than 935,000 to more than 1.21 million, an increase from 69.2 percent to 89.6 percent by 1967. In 1966, no African Americans were serving in either the State Senate or the State House. By 1968, 24 African Americans were serving in state or local offices and the number would grow slowly over the years at the state level. In a little more than 25 years, there were five African Americans serving in the Senate and 18 in the House.

Lowndes County Voters

Within two years after passage, more than half of eligible African Americans in Alabama (51.2 percent) had registered to vote, rising from fewer than 93,000 to more than 248,000, according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. The law suspended the use of questionnaires and imposed federal officials and election examiners to oversee the registration process, which had been formerly controlled by local boards of registrars who actively impeded black registrants. Some 60,000 individuals were aided by these officials. That number included more than 19,000 voters in Jefferson County and 9,000 in Montgomery County. In Dallas County, where only 320 out of more than 15,000 eligible African American voters had been registered, nearly 9,000 were signed up to vote. In 1964, in Lowndes and Wilcox Counties, there were no African Americans registered to vote, but 59.1 percent and 62.1 percent had been registered, respectively, by 1967. These strides prompted Gov. George Wallace to mobilize more white Alabamians to register as well, from more than 935,000 to more than 1.21 million, an increase from 69.2 percent to 89.6 percent by 1967. In 1966, no African Americans were serving in either the State Senate or the State House. By 1968, 24 African Americans were serving in state or local offices and the number would grow slowly over the years at the state level. In a little more than 25 years, there were five African Americans serving in the Senate and 18 in the House.

Voter Suppression Continued

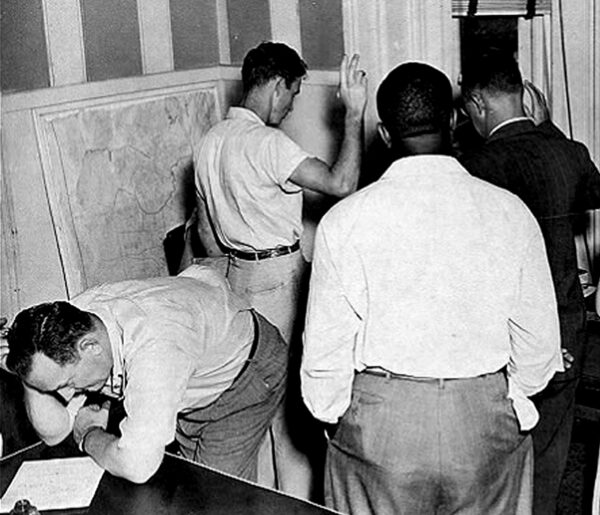

Lucius Amerson and Deputies Sworn In

Although passage of the act led to large increases in African American voter registrations, it did not end efforts to suppress the African American vote. In some counties, the Democratic executive committees shifted from district-based elections to countywide elections to select their members, effectively preventing African Americans from serving. The effort in Barbour County was challenged in the 1966 case Smith v. Paris and upheld in a higher court. The Barbour County Democratic Executive Committee defied the court, however, and was sued by the federal government. A federal court also countermanded an attempt by the state legislature in fall 1965 to redraw a U.S. House district boundary that would have placed predominantly African American Macon and Bullock Counties into a district with white majority counties. Federal authorities found other allegations of irregularities and discrimination as well in 1966. The Lowndes County Democratic Executive Committee raised filing fees for candidates from $50 to $500, although annual per capita income averaged only $507 in the heavily African American county. Officials found that in other Black Belt counties, whites cast illegal votes and election officials provided insufficient aid for illiterate African Americans voters, such as sample ballots, even mismarking ballots for white candidates and interfering with poll watchers.

Lucius Amerson and Deputies Sworn In

Although passage of the act led to large increases in African American voter registrations, it did not end efforts to suppress the African American vote. In some counties, the Democratic executive committees shifted from district-based elections to countywide elections to select their members, effectively preventing African Americans from serving. The effort in Barbour County was challenged in the 1966 case Smith v. Paris and upheld in a higher court. The Barbour County Democratic Executive Committee defied the court, however, and was sued by the federal government. A federal court also countermanded an attempt by the state legislature in fall 1965 to redraw a U.S. House district boundary that would have placed predominantly African American Macon and Bullock Counties into a district with white majority counties. Federal authorities found other allegations of irregularities and discrimination as well in 1966. The Lowndes County Democratic Executive Committee raised filing fees for candidates from $50 to $500, although annual per capita income averaged only $507 in the heavily African American county. Officials found that in other Black Belt counties, whites cast illegal votes and election officials provided insufficient aid for illiterate African Americans voters, such as sample ballots, even mismarking ballots for white candidates and interfering with poll watchers.

Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder

In April 2010, a strong challenge to the VRA came before the federal courts when Shelby County, Alabama, filed suit in Washington, D.C., petitioning to declare Section 5 of the VRA unconstitutional. Section 5, also known as the "preclearance provision," requires certain jurisdictions, such as cities, counties, and states with a history of discrimination, to obtain federal approval before changing voting procedures, such as moving or closing polling places or redrawing boundaries. The provision was upheld in several lower courts in the case known as Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder but was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in June 2013. The Supreme Court ruled that the coverage formula in Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act—which determines which jurisdictions are covered by Section 5—is unconstitutional because it is based on an old formula. Therefore, Congress would need to enact a new coverage formula, the court suggested.

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), the American Civil Liberties Union, and the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice among others have argued that after Shelby, states and local jurisdictions have made changes to voting requirements that impede voting for minorities and people of color. The SPLC noted in a 2020 report that in the several decades prior to Shelby, preclearance provisions prevented more than 100 changes in Alabama alone because of their discriminatory impact. After the Shelby decision, Alabama closed polling places, mostly in largely African American counties, purged voter rolls, and instituted voter identification laws that some observers claim suppress the vote. The state was heavily criticized in 2015 for closing drivers' license offices (ostensibly for budgetary reasons), which issue the most common voter ID, drivers' licenses, mostly in Black Belt counties with majority African American populations. The state later reopened them after the public outcry. Five years after Shelby, the Commission on Civil Rights found that numerous states instituted similar voting procedures that have been particularly harmful to minorities and the poor. At the national level, Congressional Democrats have pushed legislation aimed at reforming election and voter registration procedures, such as making registration easier, ending gerrymandering, and improving election security.

Further Reading

- Bullock, Charles S., and Ronald Keith Gaddie. The Triumph of Voting Rights in the South. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.

- Davidson, Chandler, and Bernard Grofman, eds. Quiet Revolution in the South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act, 1965-1990. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Foster, Lorn S., ed. The Voting Rights Act: Consequences and Implications. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1985.

- Garrow, David J. Protest at Selma: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1978.

- Thornton, J. Mills, III. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham and Selma. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.