Alabama Literature

To Kill A Mockingbird

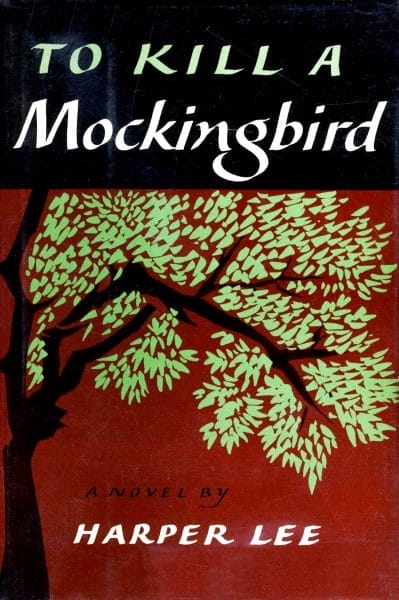

Alabama has a rich literary heritage and can boast of extraordinary literary activity and achievement in the present, including such genres as travel and nature writing, autobiography, and humor, as well as poetry, drama, and fiction. Among well-known writers either from Alabama or with strong Alabama connections are William Bartram, Philip Henry Gosse, Carl Carmer, Booker T. Washington, Zora Neale Hurston, Harper Lee, Truman Capote, Walker Percy, Winston Groom, and Fannie Flagg. With Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), Alabama joined the rare company of states that have contributed a classic not only to American but also to world literature.

To Kill A Mockingbird

Alabama has a rich literary heritage and can boast of extraordinary literary activity and achievement in the present, including such genres as travel and nature writing, autobiography, and humor, as well as poetry, drama, and fiction. Among well-known writers either from Alabama or with strong Alabama connections are William Bartram, Philip Henry Gosse, Carl Carmer, Booker T. Washington, Zora Neale Hurston, Harper Lee, Truman Capote, Walker Percy, Winston Groom, and Fannie Flagg. With Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), Alabama joined the rare company of states that have contributed a classic not only to American but also to world literature.

Early writings emerging from what would become the state of Alabama prefigure a number of literary focuses and forms that would later help define the literary output of the state. André Pénigaut, who wrote about the French presence along the Gulf Coast in the early eighteenth century and has been called Alabama’s first literary figure, reported the life and culture of the indigenous peoples of the region. So also did William Bartram in his 1791 Travels, although Bartram directed his interest more toward the native fauna and, especially, flora.

The Red Eagle: A Poem of the South

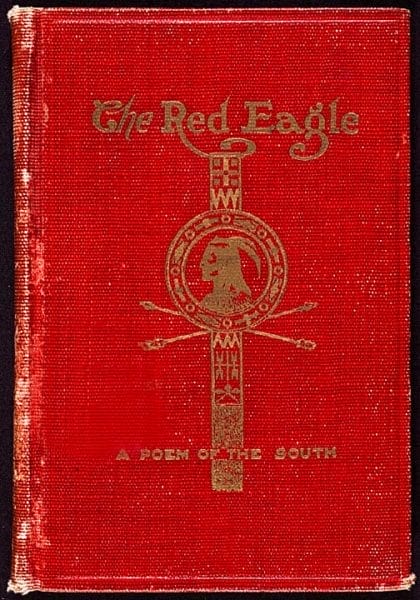

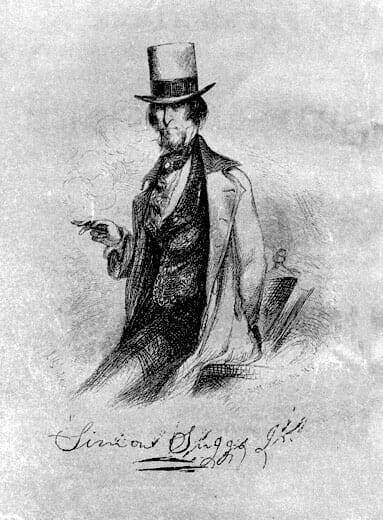

European-American conflict with Native Americans and specifically the Creek War of 1813-1814 was the subject of more traditional literary efforts, both poetry and prose and both serious and not. Lewis Sewall’s The Last Campaign of Sir John Falstaff II, Or, The Hero of the Burnt-Corn Battle; A Serio-Comic Poem appeared in 1815, and the Creek leader William Weatherford was the epic title hero of Alexander Beaufort Meek’s The Red Eagle, a lengthy poem in varying verse forms published in New York in 1855 and achieving at least five subsequent editions. The first novel published in Alabama, in 1833, was written by “Don Pedro Cassender” (actually, either Wiley Connor or Michael Smith) and titled The Lost Virgin of the South; An Historical Novel, Founded on Facts, Connected with the Indian War in the South, in 1812 to ’15. A quite different kind of book—humorous, satiric short stories—was Johnson Jones Hooper’s widely read Some Adventures of Captain Simon Suggs (1845), which grew out of the turbulent period of Indian removal in 1836-37.

The Red Eagle: A Poem of the South

European-American conflict with Native Americans and specifically the Creek War of 1813-1814 was the subject of more traditional literary efforts, both poetry and prose and both serious and not. Lewis Sewall’s The Last Campaign of Sir John Falstaff II, Or, The Hero of the Burnt-Corn Battle; A Serio-Comic Poem appeared in 1815, and the Creek leader William Weatherford was the epic title hero of Alexander Beaufort Meek’s The Red Eagle, a lengthy poem in varying verse forms published in New York in 1855 and achieving at least five subsequent editions. The first novel published in Alabama, in 1833, was written by “Don Pedro Cassender” (actually, either Wiley Connor or Michael Smith) and titled The Lost Virgin of the South; An Historical Novel, Founded on Facts, Connected with the Indian War in the South, in 1812 to ’15. A quite different kind of book—humorous, satiric short stories—was Johnson Jones Hooper’s widely read Some Adventures of Captain Simon Suggs (1845), which grew out of the turbulent period of Indian removal in 1836-37.

Coming out of the state many years later was the nationally embraced The Education of Little Tree (1976), which appeared to be a poignant autobiographical account of a modern Cherokee Indian boy. In fact, it was a literary hoax written not by “Forrest Carter” but by Asa Carter, a white supremacist who authored Gov. George Wallace’s infamous 1963 “Segregation Today, Segregation Tomorrow, Segregation Forever” inauguration speech.

Depictions of War

Macaria Decorative Cover

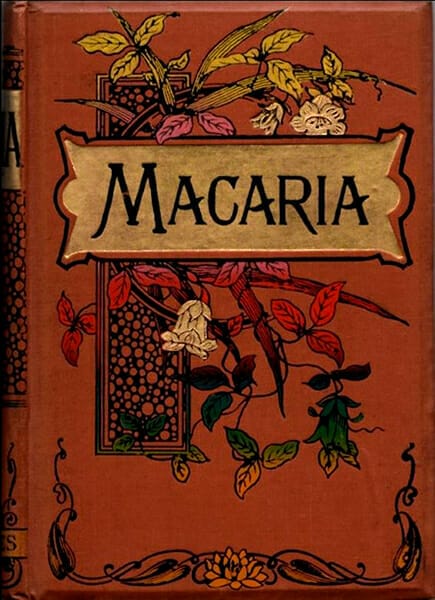

Beyond the violent early confrontation with Native Americans, warfare has occupied an unusually large number of writers with Alabama connections. Poets such as Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar and Theodore O’Hara found inspiration in the U. S.-Mexican War of 1846-48, O’Hara’s “The Bivouac of the Dead” becoming the nation’s most quoted elegiac tribute to the casualties of military combat. Despite Mobile’s being known as the “Capital of Lost Cause Poetry” in the later nineteenth century, the literary impact of the Civil War was diffuse and divergent. Among the earliest Civil War novels to be published in a reuniting nation, Tobias Wilson: A Tale of the Great Rebellion (1865) was anti-Confederate—written by Jeremiah Clemens, a relative of Mark Twain and a former U.S. senator from Alabama. Alabama native and Confederate veteran Kittrell J. Warren’s Life and Public Services of an Army Straggler, a burlesque parody of soldiering, also appeared in 1865. More sympathetically southern were Augusta Jane Evans Wilson’s Macaria (1863) and the 1867 novels of the Confederate veteran brothers Sidney and Clifford Lanier: Tiger-Lilies and Thorn-Fruit, respectively (both written in Montgomery), which reflected their combat experiences. Also in that vein was Mary Anne Cruse’s Cameron Hall: A Story of the Civil War, written during the war and focusing on the devastated home front; it found a northern publisher in 1867. Several noteworthy Civil War novels from state residents appeared considerably later, including Andrew Lytle‘s The Long Night (1936) and Perry Lentz’s The Falling Hills (1967) and It Must Be Now the Kingdom Coming (1973).

Macaria Decorative Cover

Beyond the violent early confrontation with Native Americans, warfare has occupied an unusually large number of writers with Alabama connections. Poets such as Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar and Theodore O’Hara found inspiration in the U. S.-Mexican War of 1846-48, O’Hara’s “The Bivouac of the Dead” becoming the nation’s most quoted elegiac tribute to the casualties of military combat. Despite Mobile’s being known as the “Capital of Lost Cause Poetry” in the later nineteenth century, the literary impact of the Civil War was diffuse and divergent. Among the earliest Civil War novels to be published in a reuniting nation, Tobias Wilson: A Tale of the Great Rebellion (1865) was anti-Confederate—written by Jeremiah Clemens, a relative of Mark Twain and a former U.S. senator from Alabama. Alabama native and Confederate veteran Kittrell J. Warren’s Life and Public Services of an Army Straggler, a burlesque parody of soldiering, also appeared in 1865. More sympathetically southern were Augusta Jane Evans Wilson’s Macaria (1863) and the 1867 novels of the Confederate veteran brothers Sidney and Clifford Lanier: Tiger-Lilies and Thorn-Fruit, respectively (both written in Montgomery), which reflected their combat experiences. Also in that vein was Mary Anne Cruse’s Cameron Hall: A Story of the Civil War, written during the war and focusing on the devastated home front; it found a northern publisher in 1867. Several noteworthy Civil War novels from state residents appeared considerably later, including Andrew Lytle‘s The Long Night (1936) and Perry Lentz’s The Falling Hills (1967) and It Must Be Now the Kingdom Coming (1973).

A decorated combat Marine in World War I, William March in his Company K (1933) produced one of the most internationally powerful novels written about that war. Robert Bowen dealt with the Pacific front of World War II in his novel The Weight of the Cross (1951), as Eugene B. Sledge did autobiographically in his acclaimed memoir With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa (1981). Korean War veteran William E. Butterworth, the most prolific writer to live in Alabama in the twentieth century, has sold millions of books of military fiction and nonfiction, many under the pseudonym of W. E. B. Griffin. Works of fiction growing out of individuals’ Vietnam War experiences include Winston Groom‘s Better Times Than These (1978) and Gustav Hasford‘s The Short-Timers (1979). Dealing with armed battle on a smaller scale, Tom Franklin’s Hell at the Breech (2002) is an impressive contemporary novel based on the so-called Mitcham War, a bloody confrontation between social classes in Clarke County in the 1890s.

Nature and Travel Writing, and Social Critique

Franklinia altamaha

William Bartram’s famous Travels created a fertile legacy for the state, realized in the nonfiction subgenres of nature writing, travel literature, and autobiography. Another engaging volume of nature writing (and talented illustration), this time by a British sojourner in Alabama, is Letters from Alabama, Chiefly Relating to Natural History (1859) by Philip Henry Gosse, who was a plantation schoolmaster in the state in 1838. Edward O. Wilson, internationally acclaimed entomologist, provocative ecologist, evolutionary theorist, and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, has authored a number of books, including the memoir Naturalist (1994). A different type of nature writing marked by its more personal essay form, Tom Kelly’s The Tenth Legion (1973) is a distinctively toned, appropriately passionate, and finely crafted book about the art of turkey hunting.

Franklinia altamaha

William Bartram’s famous Travels created a fertile legacy for the state, realized in the nonfiction subgenres of nature writing, travel literature, and autobiography. Another engaging volume of nature writing (and talented illustration), this time by a British sojourner in Alabama, is Letters from Alabama, Chiefly Relating to Natural History (1859) by Philip Henry Gosse, who was a plantation schoolmaster in the state in 1838. Edward O. Wilson, internationally acclaimed entomologist, provocative ecologist, evolutionary theorist, and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, has authored a number of books, including the memoir Naturalist (1994). A different type of nature writing marked by its more personal essay form, Tom Kelly’s The Tenth Legion (1973) is a distinctively toned, appropriately passionate, and finely crafted book about the art of turkey hunting.

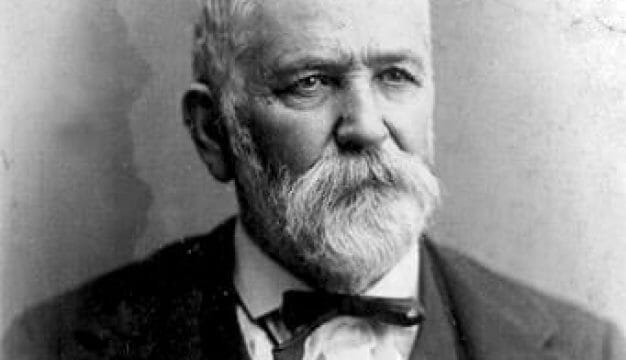

Philip Henry Gosse

Philip Henry Gosse also wrote perceptively about the human inhabitants of Alabama, as did another sojourner, Anne Royall, who produced a book with the same title as his, Letters from Alabama, in 1830. The subtitle of Royall’s book, however, was On Various Subjects, fitting and predictive for an author who was one of the first women in the United States to succeed as a muckraking journalist in Washington, D.C. Social critic and sometime Florence resident Rebecca Harding Davis is best known for her novel Life in the Iron-Mills, set in Massachusetts, but she also wrote perceptively about the New South in her serialized work “Here and There in the South,” which appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1887 and was set in Alabama. Both written by native Alabamians, Daniel R. Hundley’s Social Relations in Our Southern States (1860) provided incisive social and cultural analysis in very readable prose, and Clarence Cason’s 90 Degrees in the Shade (1935) did the same thing the following century. A nonnative but residential perspective was offered in Carl Carmer’s best-selling Stars Fell on Alabama (1934), while a nonresident’s travel back to his home state yielded the very rich South to a Very Old Place (1971) by Albert Murray. James Agee’s and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) offers a highly personal, outsider account of limited time spent with west Alabama sharecropper families during the Great Depression. The work combines Agee’s powerful prose with Evans’s stark photographs and is an artful tour de force that defies conventional classification. Focusing closer to its author’s home, Dennis Covington’s Salvation on Sand Mountain was a National Book Award finalist in 1995.

Philip Henry Gosse

Philip Henry Gosse also wrote perceptively about the human inhabitants of Alabama, as did another sojourner, Anne Royall, who produced a book with the same title as his, Letters from Alabama, in 1830. The subtitle of Royall’s book, however, was On Various Subjects, fitting and predictive for an author who was one of the first women in the United States to succeed as a muckraking journalist in Washington, D.C. Social critic and sometime Florence resident Rebecca Harding Davis is best known for her novel Life in the Iron-Mills, set in Massachusetts, but she also wrote perceptively about the New South in her serialized work “Here and There in the South,” which appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1887 and was set in Alabama. Both written by native Alabamians, Daniel R. Hundley’s Social Relations in Our Southern States (1860) provided incisive social and cultural analysis in very readable prose, and Clarence Cason’s 90 Degrees in the Shade (1935) did the same thing the following century. A nonnative but residential perspective was offered in Carl Carmer’s best-selling Stars Fell on Alabama (1934), while a nonresident’s travel back to his home state yielded the very rich South to a Very Old Place (1971) by Albert Murray. James Agee’s and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) offers a highly personal, outsider account of limited time spent with west Alabama sharecropper families during the Great Depression. The work combines Agee’s powerful prose with Evans’s stark photographs and is an artful tour de force that defies conventional classification. Focusing closer to its author’s home, Dennis Covington’s Salvation on Sand Mountain was a National Book Award finalist in 1995.

Alabamians also have written about their travels elsewhere. The most prominent nineteenth-century example is Octavia Walton Le Vert’s two-volume Souvenirs of Travel (1857) about Europe, which, ironically, attracted famous visitors from all over the world to her salon in Mobile. A twentieth-century Mobile example would be Jay Higginbotham’s Fast Train Russia (1983). Montgomery-born syndicated columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson has published her affecting accounts of other U.S. locales in two books, and journalist, poet, and novelist Wayne Greenhaw, who divided his time between Alabama and Mexico, wrote movingly about both of these homes.

Autobiography

Angela Davis in Germany

For more straightforward autobiography, Alabama has claim to two American classics: Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery (1901) and Helen Keller‘s The Story of My Life (1903). An earlier example is the 1889 Reminiscences of a Long Life by poet, politician, and publisher William Russell Smith, who has been called “the father of Alabama literature.” A slave-narrative precedent for the state’s extensive African American autobiography, a literary type that historically involved transcription by another person, was the Narrative of James Williams, An American Slave, Who Was for Several Years a Driver on a Cotton Plantation in Alabama (1838), which raised debate in the contemporary press about its authenticity. Co-written life stories following Up from Slavery in this direct lineage have come, in the later twentieth century, from Nate Shaw (also known as Ned Cobb), Onnie Lee Logan, Sara Brooks, Sara Rice, J. L. Chestnut Jr., and Rosa Parks. Beginning in the 1930s, African Americans who published autobiographies that have connections to Alabama include Angelo Herndon, Hosea Hudson, Angela Davis, James Haskins, Willie Ruff, Ellen Tarry, Deborah McDowell, and Trudier Harris.

Angela Davis in Germany

For more straightforward autobiography, Alabama has claim to two American classics: Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery (1901) and Helen Keller‘s The Story of My Life (1903). An earlier example is the 1889 Reminiscences of a Long Life by poet, politician, and publisher William Russell Smith, who has been called “the father of Alabama literature.” A slave-narrative precedent for the state’s extensive African American autobiography, a literary type that historically involved transcription by another person, was the Narrative of James Williams, An American Slave, Who Was for Several Years a Driver on a Cotton Plantation in Alabama (1838), which raised debate in the contemporary press about its authenticity. Co-written life stories following Up from Slavery in this direct lineage have come, in the later twentieth century, from Nate Shaw (also known as Ned Cobb), Onnie Lee Logan, Sara Brooks, Sara Rice, J. L. Chestnut Jr., and Rosa Parks. Beginning in the 1930s, African Americans who published autobiographies that have connections to Alabama include Angelo Herndon, Hosea Hudson, Angela Davis, James Haskins, Willie Ruff, Ellen Tarry, Deborah McDowell, and Trudier Harris.

Rick Bragg

Some nationally published autobiographies intimately connected to Alabama places and people are volumes by Viola Goode Liddell, Kathryn Tucker Windham, Nancy Huddleston Packer, Judith Hillman Patterson, and Patricia Foster. Recently, wide attention has been given to Barbara Robinette Moss’s Change Me into Zeus’s Daughter (2000) and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Rick Bragg’s trilogy about his family, which begins with All Over but the Shoutin’ (1997). Published outside the region, Alan Shelton’s Dreamworlds of Alabama appeared in 2007, and Melissa J. Delbridge’s Family Bible in 2008.

Rick Bragg

Some nationally published autobiographies intimately connected to Alabama places and people are volumes by Viola Goode Liddell, Kathryn Tucker Windham, Nancy Huddleston Packer, Judith Hillman Patterson, and Patricia Foster. Recently, wide attention has been given to Barbara Robinette Moss’s Change Me into Zeus’s Daughter (2000) and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Rick Bragg’s trilogy about his family, which begins with All Over but the Shoutin’ (1997). Published outside the region, Alan Shelton’s Dreamworlds of Alabama appeared in 2007, and Melissa J. Delbridge’s Family Bible in 2008.

Children’s Literature

A nineteenth-century Alabama book that became a national children’s classic was Diddie, Dumps, and Tot (1882) by Louise Clarke Pyrnelle. It was a forerunner of other popular young-reader books featuring minorities to come out of the state, including writer-illustrator Annie Vaughan Weaver’s Frawg (1930). Ultimately, many quite different works of juvenile, adolescent, or young adult literature were to follow. Their authors, both black and white—and a number of them the winners of special awards in these publication fields over the years—include Maud McKnight Lindsay, Rose B. Knox, Ellen Tarry, Wyatt Blassingame, Hilary Milton, Lucile Watkins Ellison, Charles Ghigna, Stephen Gresham, Faye Gibbons, James Haskins, Ann Waldron, Nancy Van Laan, Julia Fields, Mark Childress, Aileen Kilgore Henderson, Jimmy Buffett, Cindy Wheeler, Janice Harrington, and Angela Johnson.

Drama

Drama is one of the few areas of literary activity in Alabama that has not proved so fertile. During the nineteenth century, traveling professionals such as Noah Ludlow, Sol Smith, and Joseph M. Field helped theater and drama to flourish in many antebellum communities. Today, the state is home to several fine theatre companies, with some commissioning local writers; however, few Alabama playwrights have found national audiences for their work. Kate Porter Lewis, whose “Alabama folkplays” were produced by the Carolina Players, was perhaps the chief exception until, recently, Rebecca Gilman’s award-winning dramas began to be produced in New York and London as well as in Chicago, her current home.

Old Southwest Humor

Simon Suggs Jr.

Dramatists Noah Ludlow, Sol Smith, and Joseph M. Field also wrote comic prose tales and sketches that place them among the so-called Old Southwest humorists, writers of a rowdy frontier literature and satiric social realism that gained both national and international readerships and that had Alabama as its center, geographically and otherwise. Hardin E. Taliaferro, Thomas Kirkman, John Gorman Barr, George Washington Harris, and, especially, Johnson Jones Hooper and Joseph Glover Baldwin all lived and wrote at one time in the state. The title of Baldwin’s well-known collection of sketches is The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi (1853). Old Southwest humor tales gained the positive attention of British authors such as Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray and directly influenced American writers such as Mark Twain and William Faulkner. Its heritage is clear in some of Alabama’s own best writers after the nineteenth century—William March, Eugene Walter, and Tom Franklin, for instance.

Simon Suggs Jr.

Dramatists Noah Ludlow, Sol Smith, and Joseph M. Field also wrote comic prose tales and sketches that place them among the so-called Old Southwest humorists, writers of a rowdy frontier literature and satiric social realism that gained both national and international readerships and that had Alabama as its center, geographically and otherwise. Hardin E. Taliaferro, Thomas Kirkman, John Gorman Barr, George Washington Harris, and, especially, Johnson Jones Hooper and Joseph Glover Baldwin all lived and wrote at one time in the state. The title of Baldwin’s well-known collection of sketches is The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi (1853). Old Southwest humor tales gained the positive attention of British authors such as Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray and directly influenced American writers such as Mark Twain and William Faulkner. Its heritage is clear in some of Alabama’s own best writers after the nineteenth century—William March, Eugene Walter, and Tom Franklin, for instance.

Early to Contemporary Fiction

Alabama has had important participants in many of the movements of American literary history, particularly those involving fiction. Caroline Lee Hentz and, especially, Augusta Jane Evans Wilson were stars in the mid-nineteenth-century vogue of the so-called domestic-sentimental novel, the best-sellers of their day. In the late nineteenth century, Samuel Minturn Peck, a state Poet Laureate, and John Trotwood Moore joined authors from across the nation in securing national readers for “local-color” stories about their home regions. Alabama’s most notable contribution to local-color literature, however, is Idora McClellan Plowman Moore’s “Betsy Hamilton” sketches.

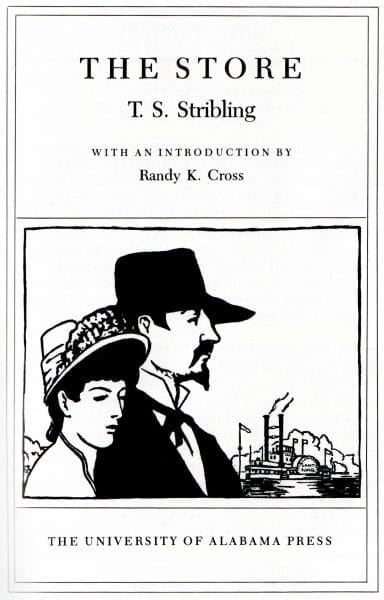

The Store

Although their reputations have not proved as enduring as those of some writers from other southern states who created the southern literary renaissance and the Harlem renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s, authors from Alabama played noteworthy roles in these movements. T. S. Stribling earned wide praise for his critical social realism in a trilogy of novels—The Forge, The Store (winner of the 1933 Pulitzer Prize), and Unfinished Cathedral. In these works, Stribling told the extended story of a family over historical time in north Alabama, just as William Faulkner did in north Mississippi. Also like Faulkner with his mythical Yoknapatawpha County, William March (the pen name of William Edward Campbell) created and peopled the imagined Pearl County in Alabama in multiple works of fiction. Remembered mostly because of his first and last novels, Company K (1933) and The Bad Seed (1954), both shocking in their different ways, March was an ironic writer who worked particularly well in short fiction. He was often compared with Faulkner in contemporary reviews, and at least one British critic thought March far superior.

The Store

Although their reputations have not proved as enduring as those of some writers from other southern states who created the southern literary renaissance and the Harlem renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s, authors from Alabama played noteworthy roles in these movements. T. S. Stribling earned wide praise for his critical social realism in a trilogy of novels—The Forge, The Store (winner of the 1933 Pulitzer Prize), and Unfinished Cathedral. In these works, Stribling told the extended story of a family over historical time in north Alabama, just as William Faulkner did in north Mississippi. Also like Faulkner with his mythical Yoknapatawpha County, William March (the pen name of William Edward Campbell) created and peopled the imagined Pearl County in Alabama in multiple works of fiction. Remembered mostly because of his first and last novels, Company K (1933) and The Bad Seed (1954), both shocking in their different ways, March was an ironic writer who worked particularly well in short fiction. He was often compared with Faulkner in contemporary reviews, and at least one British critic thought March far superior.

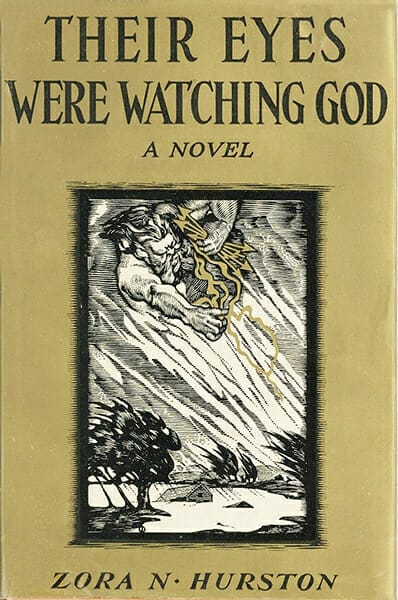

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Zora Neale Hurston and George Wylie Henderson are the most notable of Alabama’s participants in the Harlem renaissance. Henderson was trained as a printer at Tuskegee Institute, close to where he was born, and in 1935 published Ollie Miss, a novel whose strong title character has been compared to the protagonist of Hurston’s 1937 masterpiece, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Born in Notasulga, not far from Henderson’s birthplace, Hurston grew up in Florida, but she wrote about the town and her parents’ lives there in her first book, Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1935).

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Zora Neale Hurston and George Wylie Henderson are the most notable of Alabama’s participants in the Harlem renaissance. Henderson was trained as a printer at Tuskegee Institute, close to where he was born, and in 1935 published Ollie Miss, a novel whose strong title character has been compared to the protagonist of Hurston’s 1937 masterpiece, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Born in Notasulga, not far from Henderson’s birthplace, Hurston grew up in Florida, but she wrote about the town and her parents’ lives there in her first book, Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1935).

Often favorably compared by reviewers with Gone with the Wind, Lella Warren’s Foundation Stone (1940) is based on her Alabama family’s history and was at one time the best-selling American novel in the world. Less regionally grounded and for a long time not considered as serious or worthy literature was the extremely popular genre of supernatural or science fiction writing, which also began to flourish at this time, literature to which Mary Counselman made impressive pioneering contributions. Two other talented women writers, Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald and Sara Haardt Mencken (both natives of Montgomery), had their work eclipsed by the reputations of their famous husbands.

Alabama’s Literary Renaissance

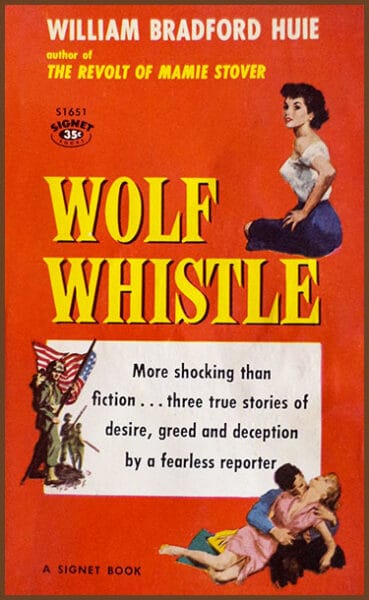

Wolf Whistle

In the 1950s and 1960s, in the second wave of the southern literary renaissance, Alabama writers were more enduringly active. Walker Percy, who was born and grew up in Birmingham and who wrote both highly respected fiction and nonfiction indebted to modern European philosophy, is one of the major figures in this activity. Eugene Walter and Borden Deal both reacted to the darkly gothic, past-haunted reputation of earlier twentieth-century southern literature. Walter, who lived in Paris and Rome for 25 years before returning to his native Mobile, won the Lippincott Prize for The Untidy Pilgrim in 1954. Deal, the most prolific of the many nationally published authors from Hudson Strode’s famous creative writing program at the University of Alabama, called for serious literary attention to contemporary southern life and society. Such attention was certainly and notoriously given by William Bradford Huie, both as novelist and as pioneering investigative journalist in, for example, Wolf Whistle and Other Stories, about the Emmett Till murder. Influenced by a class- and race-conscious coming of age in Birmingham, poet John Beecher devoted a lifetime to human-rights in his writing, which was directly in the protest tradition.

Wolf Whistle

In the 1950s and 1960s, in the second wave of the southern literary renaissance, Alabama writers were more enduringly active. Walker Percy, who was born and grew up in Birmingham and who wrote both highly respected fiction and nonfiction indebted to modern European philosophy, is one of the major figures in this activity. Eugene Walter and Borden Deal both reacted to the darkly gothic, past-haunted reputation of earlier twentieth-century southern literature. Walter, who lived in Paris and Rome for 25 years before returning to his native Mobile, won the Lippincott Prize for The Untidy Pilgrim in 1954. Deal, the most prolific of the many nationally published authors from Hudson Strode’s famous creative writing program at the University of Alabama, called for serious literary attention to contemporary southern life and society. Such attention was certainly and notoriously given by William Bradford Huie, both as novelist and as pioneering investigative journalist in, for example, Wolf Whistle and Other Stories, about the Emmett Till murder. Influenced by a class- and race-conscious coming of age in Birmingham, poet John Beecher devoted a lifetime to human-rights in his writing, which was directly in the protest tradition.

Historical civil rights concerns, of course, lie at the heart of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), and this Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, set in 1930s Alabama, achieved for that concern a humane universality that brought Lee international celebrity. Another widely known writer capable of writing with moving tenderness about youthful life in small-town Alabama was Truman Capote, a childhood playmate of Harper Lee and the model for one of her characters in Mockingbird. Other writers native to the state or with significant Alabama connections who secured major national publishers and favorable critical reviews include James Still, Elise Sanguinetti, Jesse Hill Ford, Margaret Walker, Ralph Ellison, and Shirley Ann Grau, whose Keepers of the House won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1965. Albert Murray, who began a sequence of autobiographical novels with his Train Whistle Guitar in 1974, produced incisive books and essays on African American and American culture that emphasize the central aesthetic of the blues.

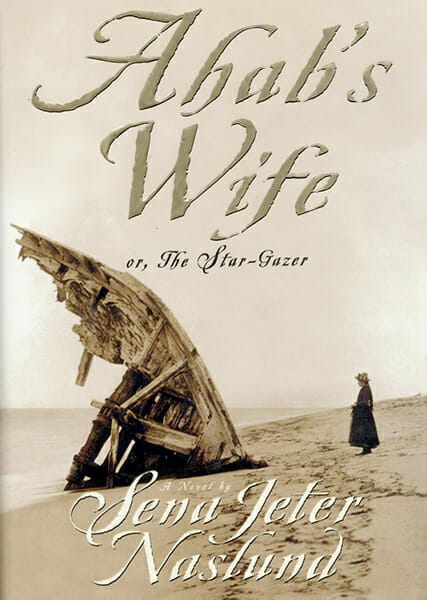

Ahab’s Wife

To characterize recent output and present literary activity in the state, literary historians are now employing such terms as “explosion” and “renaissance.” The idea of renaissance or rebirth is wonderfully symbolized in the careers of two writers who gained national critical attention later in their lives. Helen Norris published her first novel in 1940, but it was not until the 1980s that her fine short stories began to appear in multiple book collections and be made into television movies. Mary Ward Brown, also with a long hiatus in her writing, was almost 70 years old when her short-story collection Tongues of Flame won the 1986 Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award for best first book of fiction by an American author. Madison Jones, who taught for 30 years at Auburn University, had his first novel published in 1957 and his most recent in 2008. His masterwork, lauded for its elements of classic tragedy, is A Cry of Absence (1971), set in Alabama during the civil rights movement. Sena Jeter Naslund, who captured a wide audience of both scholars and general readers with Ahab’s Wife in 1999, also produced a novel dealing with this turbulent time: Four Spirits emerged from her deeply personal knowledge of 1960s Birmingham and, centrally, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing.

Ahab’s Wife

To characterize recent output and present literary activity in the state, literary historians are now employing such terms as “explosion” and “renaissance.” The idea of renaissance or rebirth is wonderfully symbolized in the careers of two writers who gained national critical attention later in their lives. Helen Norris published her first novel in 1940, but it was not until the 1980s that her fine short stories began to appear in multiple book collections and be made into television movies. Mary Ward Brown, also with a long hiatus in her writing, was almost 70 years old when her short-story collection Tongues of Flame won the 1986 Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award for best first book of fiction by an American author. Madison Jones, who taught for 30 years at Auburn University, had his first novel published in 1957 and his most recent in 2008. His masterwork, lauded for its elements of classic tragedy, is A Cry of Absence (1971), set in Alabama during the civil rights movement. Sena Jeter Naslund, who captured a wide audience of both scholars and general readers with Ahab’s Wife in 1999, also produced a novel dealing with this turbulent time: Four Spirits emerged from her deeply personal knowledge of 1960s Birmingham and, centrally, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing.

Among the many other contemporary writers in or from the state, including poets, who have gained more than regional recognition are Sonia Sanchez, Gail Godwin, William Cobb, Andrew Hudgins, Rodney Jones, Mark Childress, C. Eric Lincoln, Caitlin R. Kiernan, Gerald Barrax, Thomas McAfee, H. E. Francis, Phyllis Alesia Perry, Howell Raines, Robert McCammon, Paul Hemphill, Robert Inman, Dennis Covington, Vicki Covington, Roy Hoffman, Michael Knight, Charles Gaines, Cassandra King, Judy Troy, Daniel Wallace, Julia Fields, Homer Hickam, and Marlin Barton.

From Print to Film

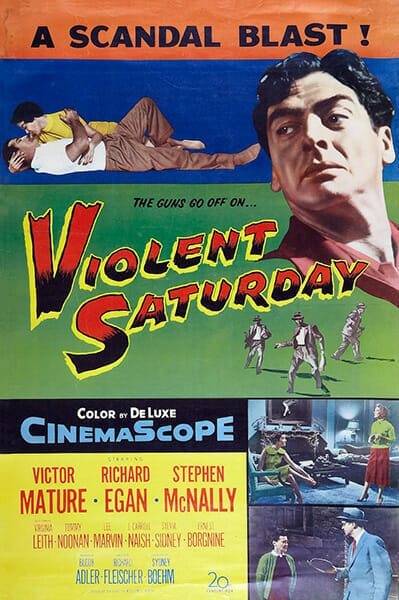

Violent Saturday Poster

Since the earliest years of silent film, works by Alabama writers have attracted filmmakers. Five of Augusta Jane Evans Wilson’s novels, including St. Elmo and At the Mercy of Tiberius, were turned into films in 1910 and 1920, for example. The most famous book and its acclaimed film version in this state contingent is, of course, To Kill a Mockingbird (1962). The Revolt of Mamie Stover (1956) and The Americanization of Emily (1964) are probably the two best known of the several movies based on the books of William Bradford Huie. The movie Wild River (1960) drew upon both Huie’s Mud on the Stars and Borden Deal’s Dunbar’s Cove. Joe David Brown’s Addie Pray was the basis for the film Paper Moon (1973); Madison Jones’s An Exile for I Walk the Line (1970); and Gustav Hasford’s The Short-Timers for Full Metal Jacket (1987). The film of William L. Heath‘s Violent Saturday (1955) retained his novel’s title. The Little Foxes, Lillian Hellman’s shocking play based on members of her mother’s Alabama family and set in Alabama, was made into a feature film in 1941, two years after it was first produced on stage. An adaptation of William March’s novel The Bad Seed was also a success on Broadway before becoming a touted Hollywood movie in 1956. More recent Alabama novels that became cinematic blockbusters, and sometimes entered cultural idiom, are Winston Groom’s Forrest Gump (1994), Fannie Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe (released as Fried Green Tomatoes in 1991), and Daniel Wallace’s Big Fish (2003). In 2005, Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God was adapted for the screen.

Violent Saturday Poster

Since the earliest years of silent film, works by Alabama writers have attracted filmmakers. Five of Augusta Jane Evans Wilson’s novels, including St. Elmo and At the Mercy of Tiberius, were turned into films in 1910 and 1920, for example. The most famous book and its acclaimed film version in this state contingent is, of course, To Kill a Mockingbird (1962). The Revolt of Mamie Stover (1956) and The Americanization of Emily (1964) are probably the two best known of the several movies based on the books of William Bradford Huie. The movie Wild River (1960) drew upon both Huie’s Mud on the Stars and Borden Deal’s Dunbar’s Cove. Joe David Brown’s Addie Pray was the basis for the film Paper Moon (1973); Madison Jones’s An Exile for I Walk the Line (1970); and Gustav Hasford’s The Short-Timers for Full Metal Jacket (1987). The film of William L. Heath‘s Violent Saturday (1955) retained his novel’s title. The Little Foxes, Lillian Hellman’s shocking play based on members of her mother’s Alabama family and set in Alabama, was made into a feature film in 1941, two years after it was first produced on stage. An adaptation of William March’s novel The Bad Seed was also a success on Broadway before becoming a touted Hollywood movie in 1956. More recent Alabama novels that became cinematic blockbusters, and sometimes entered cultural idiom, are Winston Groom’s Forrest Gump (1994), Fannie Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe (released as Fried Green Tomatoes in 1991), and Daniel Wallace’s Big Fish (2003). In 2005, Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God was adapted for the screen.

Further Reading

- Beidler, Philip, ed. The Art of Fiction in the Heart of Dixie: An Anthology of Alabama Writers. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1986.

- ———, ed. Many Voices, Many Rooms: A New Anthology of Alabama Writers. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998.

- ———. First Books: The Printed Word and Cultural Formation in Early Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

- Caton, Bill. Fighting Words: Words on Writing from 21 of the Heart of Dixie’s Best Contemporary Authors. Montgomery, Ala.: Black Belt Press, 1995.

- Colquitt, James E., ed. Alabama Bound: Contemporary Stories of a State. Livingston, Ala.: Livingston Press, 1995.

- Going, William T. Essays on Alabama Literature. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1975.

- Lamar, Jay, and Jeanie Thompson, eds. The Remembered Gate: Memoirs by Alabama Writers. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

- McIver, Jean P., and James P. White, eds. Black Alabama. Montrose, Ala.: Texas Center for Writers Press, 1997.

- Noble, Don, ed. Climbing Mt. Cheaha: Emerging Alabama Writers. Livingston, Ala.: Livingston Press, 2004.

- ———. A State of Laughter: Comic Fiction from Alabama. Livingston, Ala.: Livingston Press, 2008.

- Taylor, Joe, and Tina N. Jones, eds. Belles’ Letters: Contemporary Fiction by Alabama Women. Livingston, Ala.: Livingston Press, 1999.

- Thompson, Jeanie, ed. Gather Up Our Voices: Selected Writings from Recipients of the Harper Lee Award for Alabama’s Distinguished Writer 1998-2007. Montgomery: Alabama Writers’ Forum, 2008.

- Walker, Sue Brannan, and J. William Chambers, eds. Whatever Remembers Us: An Anthology of Alabama Poetry. Mobile, Ala.: Negative Capability Press, 2007.

- Williams, Benjamin Buford. A Literary History of Alabama: The Nineteenth Century. Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1979.