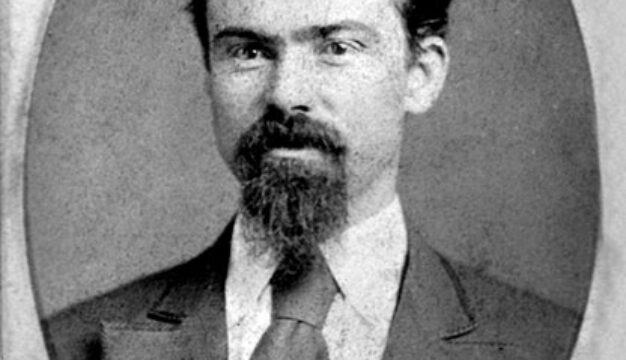

Daniel Hundley

Lawyer and author Daniel Hundley (1832-1899) is best known for his widely read Social Relations In Our Southern States, his attempt at a social-science-based analysis of class structure in the antebellum South. Although opposed to secession, he gave up significant property holdings in Chicago, Illinois, to return to his home in Alabama. He served in the Confederate army and was a prisoner of war, an experience he documented in a diary that he later published. He lived a quiet life as an attorney after the war, dying in relative obscurity.

Daniel Robinson Alexander Campbell Hundley was born in Madison County on December 11, 1832, to John Henderson and Melinda Robinson Hundley; he was one of six children. He attended schools in Alabama and Tennessee before enrolling at Bacon College in Harrodsburg, Kentucky. Hundley decided on a career in law and took courses at the University of Virginia before attending Harvard, where he graduated with a degree in law in 1853. On September 3, 1853, he married Mary Ann Hundley, a cousin, from Charlotte County, Virginia; they would eventually have seven children together. The couple moved to Alabama and made their home near Mooresville in Limestone County. In 1856, he was offered a position as manager of his father-in-law's real estate business in Chicago, Illinois, so he obtained an Illinois law license and set up a practice there.

While living in the north in the years before the Civil War, Hundley was frequently annoyed by the popular stereotypes of southerners he read and heard there. He particularly objected to the stereotypes he claimed were promoted in northern newspapers and novels such as Uncle Tom's Cabin. In these works, the South was portrayed as a three-class society, made up only of planters, poor whites, and slaves. Hundley thus began writing Social Relations In Our Southern States, which he published in 1860. In the work, Hundley uses social science language to address those misrepresentations, accurately pointing out that most white southerners belonged to the middle class. Hundley then, however, stretches his findings by sub-dividing southern society into eight supposed classes of his own invention: the southern gentleman, the middle class, the southern Yankee, the cotton snobs, the southern yeoman, the southern bully, the poor white trash, and the slave. He claims in that work that Yankees made up the majority of cotton snobs and southern bullies. At publication, the book went virtually unnoticed as the country was preoccupied with events leading up to the Civil War. Only one review has been found in a magazine of the time.

Hundley's eight social classes would not hold up among modern demographers, and his bias in favor of the southern gentleman shows clearly in the book. His chief contribution, one recognized by later historians such as Alabama native Frank Owsley, is his emphasis on the yeoman and middle classes in the South.

Although Hundley was opposed to secession, he gave up extensive property holdings in Chicago to move his family back to Alabama as the country edged toward war. When Alabama seceded, he recruited Company D of the 2nd Confederate Infantry and was elected its captain. In April 1862, he was appointed colonel of the 31st Alabama Infantry Regiment. Hundley was wounded in action at Port Gibson, Mississippi, in May 1863, and while leading his regiment in the Atlanta campaign was captured at Big Shanty, Georgia, on June 15, 1864. He was sent to the federal prison for Confederate officers on Johnson's Island in Lake Erie, near Sandusky, Ohio. Hundley kept a diary throughout his imprisonment and took it with him when he escaped on January 2, 1865. He was captured several days later, and his diary was taken from him. He was returned to Johnson's Island and remained there until he was released from the prison on July 25, 1865.

Hundley returned to his home, Hundley Hill, near Mooresville, and to his law practice. In 1874, he received a letter from a man in New York who had located his prison diary and a few weeks later received the 186-page diary in the mail. After filling in some gaps in his account and inserting an introduction, Hundley published the material in 1874 as Prison Echoes of the Great Rebellion. Unlike many war recollections, the work details events that were recorded as they happened rather than years later from memory. While the introduction was somewhat conciliatory, Hundley apparently changed none of the strong remarks and criticisms of his captors included in the diary.

Hundley stayed out of the limelight after the publication of his diary, practicing law and briefly serving as editor of the North Alabama Reporter. He died at his home on December 27, 1899, and is buried in Maple Hill Cemetery in Huntsville, Madison County.

Additional Resources

Allardice, Bruce S. Confederate Colonels. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2008.

Cooper, William J. Jr. "Daniel R. Hundley: Interpreter of the Antebellum South." In Social Relations in the Old South by Daniel R. Hundley. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979.

Williams, Benjamin B. A Literary History of Alabama: The Nineteenth Century. Madison, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1979.