Thomas Fearn

Thomas Fearn (1789-1863) was a prominent physician and surgeon in early Huntsville, Madison County, and is generally credited with discovering the healing properties of quinine for treating malaria. Fearn also was an important developer of Huntsville, along with his brothers George and Robert. His first public works project was the Indian Creek Canal connecting Huntsville’s Big Spring to the Tennessee River, while the trio helped rebuild Alabama’s first public water systems. Fearn would acquire much real estate through which he became a wealthy cotton plantation owner and one of the largest slaveholders in the county.

Fearn was born on November 15, 1789, to Thomas Fearn and Mary Burton Fearn in Pittsylvania County, Virginia. Sources differ on the number and gender, but he had perhaps six siblings born to this union and several half siblings from his father’s previous marriage. He graduated from Washington Academy (present-day Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, in 1806, and then decided to pursue a medical career in Philadelphia, where he graduated from the Old Medical College in 1810. After graduation, he moved to the small village of Twickenham in what was then the Mississippi Territory. The village was renamed Huntsville in 1811.

In Huntsville, Fearn formed a partnership with John McGhee, also a doctor, to establish a successful practice that treated prominent members of the community. In 1813, Fearn joined other doctors who became army surgeons during the War of 1812 and Creek War of 1813-14. Gen. Andrew Jackson highly regarded Fearn, who reportedly treated some of Jackson’s wounds. Jackson named Fearn chief surgeon and placed him in charge of the military hospital in Huntsville, where he treated the army’s sick and wounded. This appointment only lasted two weeks, however, because Jackson defeated the Red Stick faction of Creeks at Horseshoe Bend on March 27, 1814, ending the Creek War. Fearn returned home and reopened his practice that year. Local history recounts that at some point, Fearn was treating a young child with a “threatening disease” for some time, but the child was not improving. So, he sent the child with a nurse to live in a cabin on the mountain adjacent to Huntsville. Within a few weeks, the child had recovered, and Fearn dubbed the mountain Monte Sano, meaning “mountain of health.”

In 1818, Fearn traveled to England and then to France to improve his medical and surgical skills. He studied under the leading surgeon of the day, Guillaume Dupuytren. As educational as this experience was, Fearn was horrified by the experimental methods of his mentor. In one notable example, a woman came in a severe, gangrenous wound on her leg that Fearn knew would need to be amputated. Dupuytren, however, decided to attempt an innovative new procedure instead. The woman did not survive the procedure, and Fearn was appalled by the lack of concern Dupuytren had for his patients’ pain and suffering.

Fearn returned to Huntsville in 1820 to the newly formed 22nd state of Alabama. He would earn a widespread reputation as a noted surgeon and is credited as the first person in North America and Europe to discover the uses of quinine, a South American tree bark, in the prevention and treatment of malaria. His article, “The Use of Quinine,” was widely published and republished, and he revolutionized the treatment of fever from malaria and typhoid.

Fearn took an interest in public service as well. In 1821, he was appointed a trustee of the newly created University of Alabama, a position he maintained until shortly before it opened for classes in 1831. In 1822, Fearn married Sallie Bledsoe Shelby, with whom he would have seven daughters. Sallie later died in 1842. That same year, he was elected to the first of three terms in state legislature, being elected again in 1828 and 1829. He was also a member of the Alabama Board of Medical Examiners from 1823 to 1829 and was elected president of the newly created Medical Society of North Alabama in 1827. He served as director of Huntsville’s Planters and Merchants Bank from 1822 until 1826.

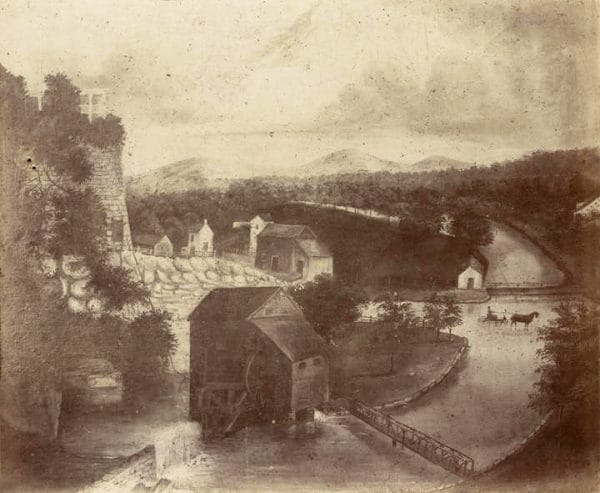

At some point, his Virginia family moved to Alabama, and Fearn formed various partnerships with his brothers, Robert and George, in real estate, cotton trading, and other business deals, foregoing medicine for these more lucrative pursuits. (George would serve a term as mayor in 1833, when Thomas was an alderman, and Robert would serve several terms as an alderman from the 1830s to the early 1850s.) Around 1820, Fearn and others, notably LeRoy Pope, began the construction of Indian Creek Canal, nicknamed Fearn’s Canal, between Big Spring and the Tennessee River, to make cotton transportation quicker and easier. They hired enslaved Blacks and free whites, paying them equally, to dig the canal. Fearn, Pope, and three others were appointed as commissioners to sell stock for the Indian Creek Navigation Company, as the project was named. But only through Fearn and his brother George was the project completed. The canal opened in 1831 and operated for about a decade before being replaced by railroads. Incidentally, George and Robert would be elected directors for the Memphis and Charleston Railroad when it was organized in 1850 in Alabama.

In 1836, the Fearn brothers bought the dilapidated Huntsville Water Works, rebuilt it, and made it functional again. Together, they commissioned the installation of new cast-iron pipes and an iron pump at Big Spring. Their newly renovated water system was one of the first west of the Appalachian Mountains and the first in Alabama. In 1858, Fearn, then sole owner, sold the water works to the city of Huntsville for $10,000 and a lifetime of free water for his Franklin Street house. Constructed in the early 1820s, the house remained in the family for several generations and was later owned by Huntsville aerospace industrialist Olin Berry King (1934-2012). It remains a notable property in the Twickenham Historic District.

Earlier in his life, Fearn was vice president of the Huntsville chapter of the American Colonization Society, whose members believed that people born into slavery should be freed at the age of 20. But in the 1860 Census, Fearn lists 82 enslaved persons in his possession, making him one of the largest slaveholders in the county. He also hired enslaved laborers for his public works projects and used his own enslaved labor on his extensive properties, which encompassed 790 acres by the time the Civil War broke out.

During the sectional crisis, Fearn believed that secession was a poor option for the future of the United States and was appalled at the thought that a state could just leave the Union. But, he served as a delegate to the 1861 Confederate Constitutional Convention held in Montgomery from late February and until early March. He also was a deputy to the First Provisional Confederate Congress from Alabama’s Sixth District representing Madison County but resigned on the opening day of the second session, April 29, possibly owing to the inconvenience of travel. Despite his opposition to secession, he remained loyal to Alabama and thus supported the war. Like other prominent Huntsville citizens, Fearn was imprisoned for his disloyalty by federal forces, who entered the city in April 1862. He was offered his freedom upon swearing an oath to the United States, but he refused. On May 7, 1862, Fearn was paroled because his failing health from pneumonia.

Fearn died in his home on Franklin Street on Jan. 16, 1863, and was buried in Maple Hill Cemetery in Huntsville.