Boswell Amendment

The Boswell Amendment was a short-lived amendment to the Alabama Constitution, enacted in 1946, that was designed to prevent African Americans from registering to vote. It was introduced in response to the Supreme Court's 1944 ruling in Smith v. Allwright, which outlawed the common practice of holding "white's only" primaries in southern states and opened the door for the widespread registration by African Americans.

Gessner T. McCorvey

After the Smith decision, conservative Alabama Democrats mounted a vigorous campaign to circumvent the ruling. Former governor Frank M. Dixon and Gessner T. McCorvey, chair of the state's Democratic Executive Committee, crafted a constitutional amendment requiring potential voters to "understand and explain" any section of the U.S. Constitution to the satisfaction of a county registrar before being allowed to register. If the person's answer did not satisfy the registrar, then the application was denied. Local registrars were given wide discretionary powers with the express purpose of using them to refuse the applications of blacks, and some poor whites, without violating the recent Smith decision.

Gessner T. McCorvey

After the Smith decision, conservative Alabama Democrats mounted a vigorous campaign to circumvent the ruling. Former governor Frank M. Dixon and Gessner T. McCorvey, chair of the state's Democratic Executive Committee, crafted a constitutional amendment requiring potential voters to "understand and explain" any section of the U.S. Constitution to the satisfaction of a county registrar before being allowed to register. If the person's answer did not satisfy the registrar, then the application was denied. Local registrars were given wide discretionary powers with the express purpose of using them to refuse the applications of blacks, and some poor whites, without violating the recent Smith decision.

Geneva County representative Edward Calhoun "Bud" Boswell introduced the amendment to the state legislature in the 1945 session. The amendment passed unanimously in the House of Representatives and was opposed by only three members of the Senate. The legislation was added to a host of amendments for voters to consider in the November 1946 general election. Dixon took the lead in promoting the Boswell Amendment to the public, crisscrossing the state and speaking to various local groups. McCorvey used his position as chair of the state Democratic Committee to ensure the amendment's passage. He persuaded the committee to allocate funds in support of the measure and then printed and distributed thousands of pamphlets throughout the state.

The most concerted opposition to the Boswell Amendment came from black Alabamians and a small cadre of more moderate white Democrats. The Alabama branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) campaigned vigorously against the amendment, as did members of the American Federation of Labor. James E. "Big Jim" Folsom, the Democratic candidate for governor, opposed the measure along with U.S. senators Lister Hill and John Sparkman. In Montgomery, librarian Juliette Hampton Morgan wrote some of her first letters to the Montgomery Advertiser in opposition to the Boswell Amendment. Future renowned author Nelle Harper Lee, then a student at the University of Alabama, penned a satirical one-act play for a campus publication lampooning the amendment and its creators.

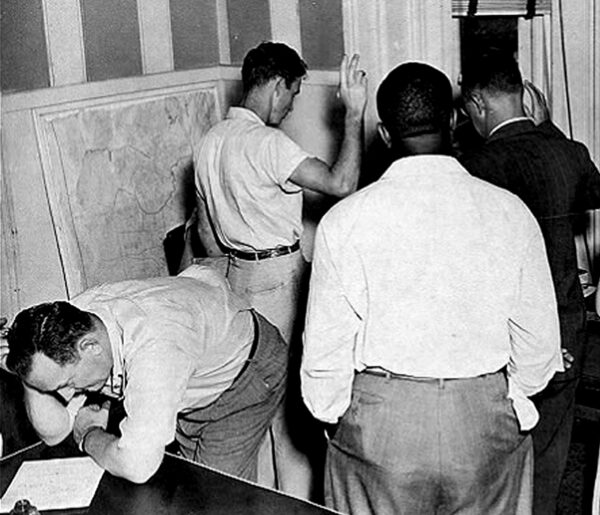

Voter Registration in Mobile

On Election Day, urban centers including Mobile and Birmingham rejected the measure, due in no small part to the vigorous campaign mounted by organized labor. Counties in north Alabama and the Wiregrass were also mixed in their support for the amendment. Despite these protests, however, the Boswell Amendment garnered 54 percent of the vote in the election and was made law. The impact of the law was made evident, when, three months after its passage, the Mobile Press published a story stating that the local board of registrars had rejected almost all of the applications by African American citizens who wished to vote.

Voter Registration in Mobile

On Election Day, urban centers including Mobile and Birmingham rejected the measure, due in no small part to the vigorous campaign mounted by organized labor. Counties in north Alabama and the Wiregrass were also mixed in their support for the amendment. Despite these protests, however, the Boswell Amendment garnered 54 percent of the vote in the election and was made law. The impact of the law was made evident, when, three months after its passage, the Mobile Press published a story stating that the local board of registrars had rejected almost all of the applications by African American citizens who wished to vote.

For several weeks after the amendment passed, members of the Alabama NAACP worked to bring a test suit to challenge the legality of the Boswell Amendment. After negotiations between members of the Birmingham and Mobile branches, it was decided that Birmingham had the stronger case. At the same time, the Voters and Veterans Association, an independent civil rights group in Mobile, was busy preparing its own battle against the amendment. The group retained George N. Leighton, an African American attorney from Chicago, who filed suit in federal court in Mobile on March 1, 1948, on behalf 10 plaintiffs. The suit alleged that the local Board of Registrars, acting under the authority of the Boswell Amendment, had denied them of their right to vote as guaranteed under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

A panel of three U.S. District Court judges heard arguments in the Davis case in late December 1948. The plaintiffs gained unexpected support from Emanuel J. "Gunny" Gonzalez, who had been appointed to the Mobile County Board of Registrars by then-Gov. Jim Folsom. Gonzalez stated that he had observed unequal treatment of black registrants by his fellow board members on numerous occasions and publically refused to testify with the two other members, Milton Schnell and Myrtle Randel.

Joseph Langan

On January 7, 1949, the judicial panel declared the Boswell Amendment unconstitutional. In the written opinion, the judges found the "understand and explain" requirement deliberately ambiguous and purposely aimed at circumventing Smith v. Allwright. In March 1949, the Supreme Court upheld the Davis decision. Soon after, McCorvey made a final effort to implement a voter qualification statute by offering a new version of the Boswell Amendment. Dubbed "Boswell, Jr.," the new proposal replaced the "understanding clause" with a requirement that voters "be of good character and embrace the duties and obligations of citizenship under the Constitution of the United States." When the vote on "Boswell, Jr." came to the floor of the Alabama State Senate on the final day of the legislative session, Mobile senator Joseph N. Langan led a successful filibuster against it.

Joseph Langan

On January 7, 1949, the judicial panel declared the Boswell Amendment unconstitutional. In the written opinion, the judges found the "understand and explain" requirement deliberately ambiguous and purposely aimed at circumventing Smith v. Allwright. In March 1949, the Supreme Court upheld the Davis decision. Soon after, McCorvey made a final effort to implement a voter qualification statute by offering a new version of the Boswell Amendment. Dubbed "Boswell, Jr.," the new proposal replaced the "understanding clause" with a requirement that voters "be of good character and embrace the duties and obligations of citizenship under the Constitution of the United States." When the vote on "Boswell, Jr." came to the floor of the Alabama State Senate on the final day of the legislative session, Mobile senator Joseph N. Langan led a successful filibuster against it.

Many of the proponents of the Boswell Amendment, including Frank Dixon and Gessner McCorvey, were key participants in the Dixiecrat Revolt of 1948 and 1949. Gunny Gonzalez later served several terms as chairman of the Mobile County Democratic Party. Joseph Langan's efforts to defeat the Boswell Amendment garnered him widespread support among Mobile's African American community during his long tenure as a city politician. George N. Leighton, the lead attorney for the plaintiffs, later served as a district judge in Illinois.

Even after the demise of the Boswell Amendment, many black Alabamians were denied the right to vote, either through continued intimidation at the polls or state action. In 1951, the Alabama legislature adopted a new voter qualification law that required potential voters to be able to read and write any section of the Constitution, be of good character, and swear that they were not part of any group or agency devoted to overthrowing the government. The new provision also required the Alabama Supreme Court to produce a uniform voter questionnaire to aid local registrars in the interview process with potential voters. The 1951 law stood until the U.S. Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Further Reading

- Barnard, William D. Dixiecrats and Democrats: Alabama Politics, 1942-1950. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1974.

- Downs, Matthew L. "James Folsom, the Boswell Amendment, and the Language of Masculinity in the Alabama Elections of 1946." Master's Thesis, Auburn University, 2004.

- Foster, Vera Chandler. "'Boswellianism:' A Technique in the Restriction of Negro Voting." Phylon Vol. 10, No. 1 (1st Quarter 1949): 26-37.

- Frederickson, Kari. The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Kirkland, Scotty E. "Mobile and the Boswell Amendment." Alabama Review 65 (July 2012): 205-49.