Alabama Black Liberation Front

The Alabama Black Liberation Front (ABLF) was a short-lived Black Power organization founded in 1970 in Birmingham, Jefferson County. Inspired by the Black Panther Party and a perceived lack of progress toward civil and voting rights, the ABLF called for armed self-defense against police brutality, Black political self-determination, and economic justice for the city’s poor and working-class Blacks. Although never a large organization, the group maintained an outsized influence by networking with a broad coalition of activists in Birmingham, including political leftists, traditional civil rights advocates, and labor organizers.

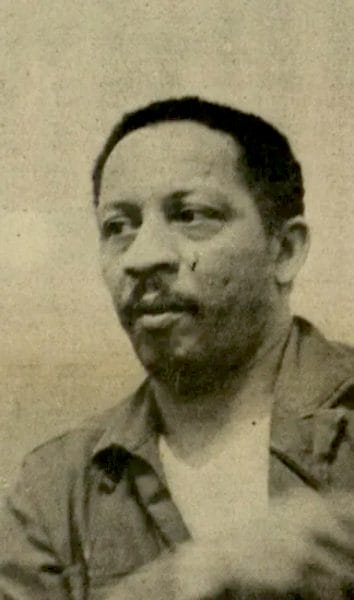

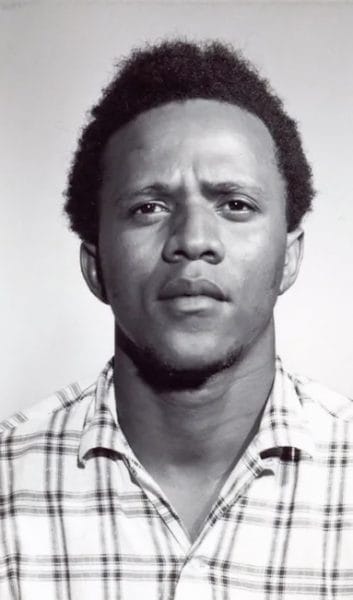

Organizing against injustice, groups such as the ABLF mobilized as part of an evolving, rather than dying, movement in Birmingham after the Campaign of 1963. Founded in May 1970, the ABLF was led by Pennsylvania native Wayland “Doc” Bryant and Birmingham-born Michael Reese. Bryant and Reese had met as members of the Georgia Black Liberation Front, which operated in the Atlanta neighborhood of Vine City. Prior to his arrival in Atlanta in the late 1960s, Bryant owned a politically radical bookstore in Greensboro, North Carolina, where he had connections to a local branch of the Black Panther Party. Bryant, older than most ABLF members at 43 years old, was a veteran of the U.S. Army as well as the civil rights movement. Reese grew up in a working-class Birmingham family, with both his father and grandfather having been miners for the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI) and had become disillusioned by what he saw as too-little progress in the living conditions of Black people. Bryant and Reese arrived in Birmingham in early 1970 to confront police violence against the city’s Black communities.

At its height, the organization counted as many as 30 official members; a majority of whom were younger men from working-class backgrounds. Many members of the ABLF, including Reese, Washington Booker III, Larry Watkins, and Charles Cannon, were also Vietnam veterans who were politically radicalized from their experience in the war. In addition. several ABLF members had previous personal interactions with law enforcement that shaped their negative views of police.

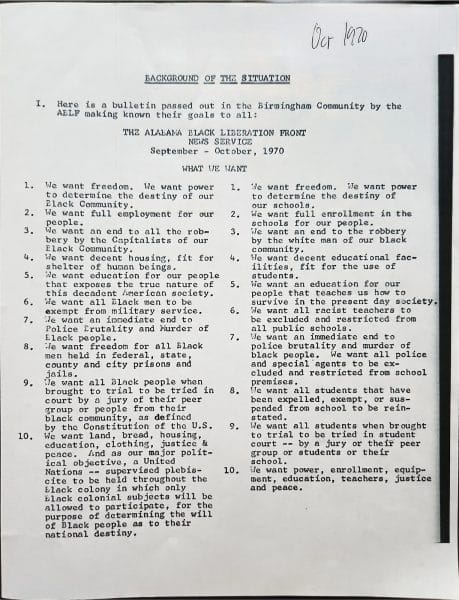

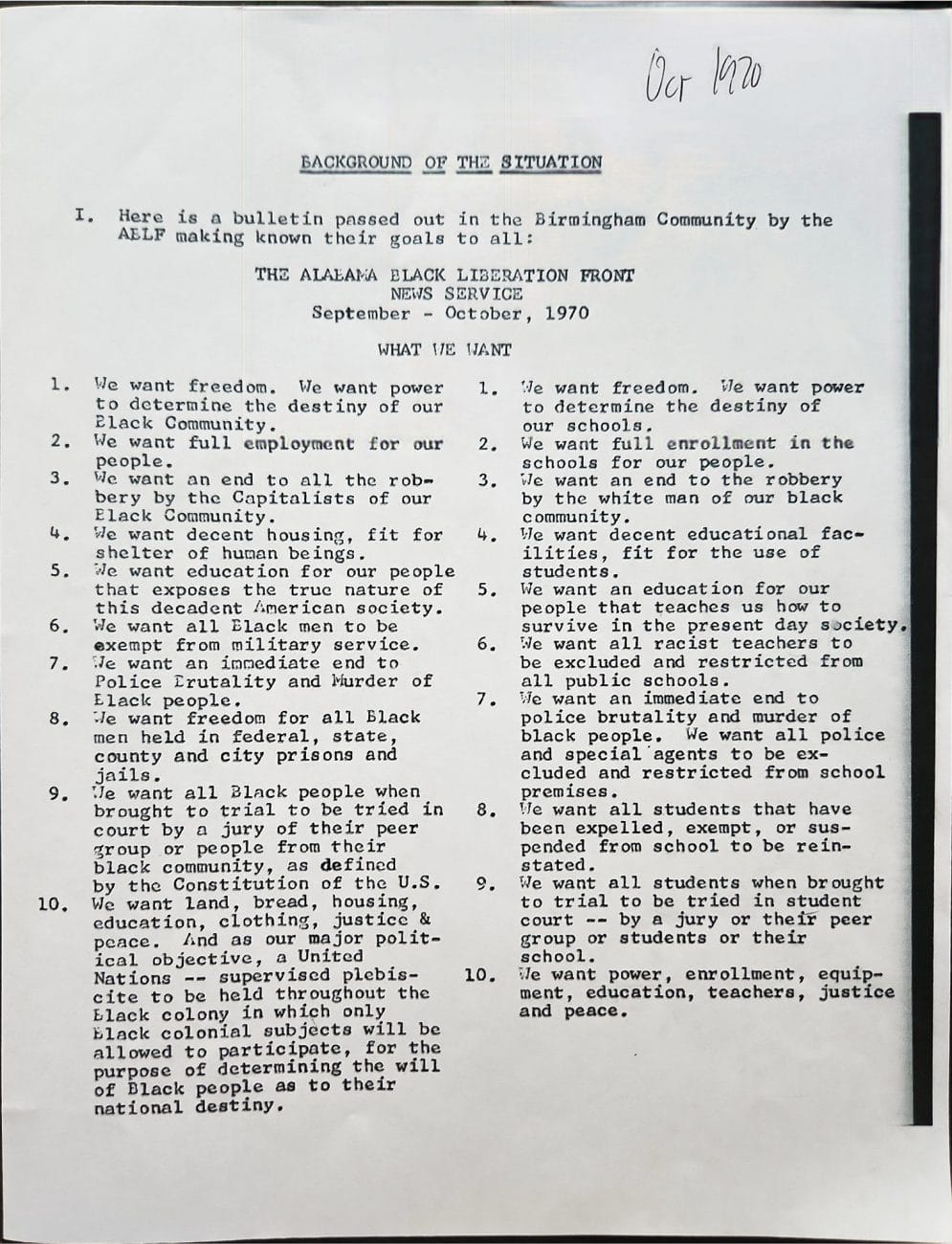

The ABLF viewed the traditional civil rights movement’s aims of integration and voting rights as insufficient in challenging a society that exploited Black workers. The ABLF instead adopted a ten-point program, modeled on the Black Panther Party’s platform, that included calls for full employment, better housing and education, and the end of police brutality towards Blacks. Further reflecting many of the members’ negative experiences in Vietnam, the ABLF also called for all Black men to be exempt from military service. Relatedly, the group embraced an anticolonial ideology, views that were influenced by the ABLF members’ experiences in Vietnam. The ABLF promoted the idea that Black Americans shared a common experience with the people pursuing decolonialization efforts in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, as those regions were all victims of white-supremacist imperialism.

Disenchanted with the slow progress of the civil rights movement, the ABLF hoped to foment an anti-capitalist revolution by the Black working class through political education and activism. This political education would spread the ABLF’s worldview by emphasizing Black political self-determination which rejected the United States’s political institutions as inherently white supremacist. The education efforts likewise called for decolonialization projects to liberate the global working class from the oppression of imperialism and advocated Black Power unionism which envisioned Birmingham’s industries controlled by the workers.

The ABLF performed several community-based services that won support from Birmingham’s Black working class. The organization formed armed patrols that tracked the police and used a short-wave radio to monitor interactions between law enforcement and Blacks. ABLF members would also arrive at these scenes as armed eyewitnesses to discourage police brutality. In addition, the ABLF established community programs to provide food and clothes to the city’s poor. In early September 1970, for instance, the organization ran a before-school breakfast program in Loveman’s Village, a public-housing community in Birmingham’s largely Black Titusville neighborhood. Birmingham police in turn expressed dismay when they interviewed public housing tenants who saw the ABLF as folk heroes in a Robin Hood-like role.

Law enforcement officials consistently surveilled and obstructed the work of the ABLF, which they characterized as a terrorist organization advocating anarchy. Jefferson County sheriff Mel Bailey pursued a campaign of deliberate harassment of the organization. On more than one occasion, the police pulled over vehicles with ABLF members inside to search for illegal firearms, but instead found and confiscated print materials on figures such as Black radicals Malcolm X and Eldridge Cleaver and Communist leaders Mao Zedong and Ho Chi Minh of China and North Vietnam, respectively.

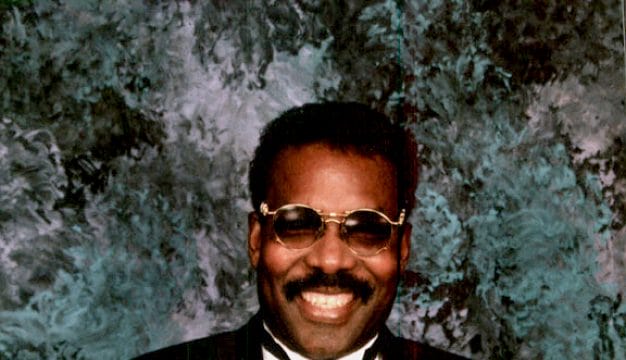

In September 1970, tensions between the ABLF and law enforcement reached a head at the home of Bernice Turner in the working-class neighborhood of Tarrant. Turner faced eviction and ABLF members Bryant, Ronald Williams, Harold Robertson, and two others stayed in Turner’s house to prevent her forced removal. On September 14, gunfire erupted following the arrival of Sheriff Bailey’s deputies, whose use of tear gas and repeated police gunfire heavily damaged Turner’s home. Law enforcement arrested Bryant and Williams for assault with intent to murder, and Bailey justified the use of force by saying they anticipated an ambush. Although media referred to the event as a “shoot-out,” all evidence supported ABLF claims that no gunfire came from within the house.

Following the arrest of Bryant and Williams, the ABLF experienced a period of increased support. A coalition of activists that included the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) and labor and human rights groups like the Southern College Educational Fund (SCEF), as well as white and Black college students, held protest rallies that characterized Bryant and Williams as political prisoners. These protests also referenced Birmingham-born Angela Davis, who was being held in jail in California after guns belonging to her were used in an armed takeover of a courtroom in Marin County. Angela’s mother, Sallye Davis, was known to have attended at least one rally. Supporters of the two men formed an organization called the Concerned Citizens for Justice (CCJ). An open letter to the city’s leadership contended Williams and Bryant were held in jail because they dared to speak out against racism and injustice. Signers of this letter included members of other working-class activist groups such as Davis Jordan of the Committee for Equal Job Opportunities (CEJO.) Bryant and Williams were ultimately found guilty of the reduced charge of assaulting an officer, with each receiving five-year prison sentences. Bryant served three years, but Williams fled Alabama for Oregon while out on bond. When Alabama attempted to extradite Williams, he was granted asylum by Oregon governor Tom McCall in January 1974.

Despite the support from activists, the arrests and the subsequent legal battles of Bryant and Williams consumed the organization’s energy and effectively ended the ABLF, which ceased operations by 1974. Though short lived, the ABLF represented the most revolutionary expression of Birmingham’s Black freedom struggle.

Further Reading

- Huntley, Horace, and John W. McKerley, eds. Foot Soldiers for Democracy: The Men, Women, and Children of the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement. Champagne-Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

- Kelley, Robin D. G. Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class. New York: Free Press, 1994.

- Lazerow, Jama, and Yohuru Williams, eds. Liberated Territory: Untold Local Perspectives on the Black Panther Party. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

- Widell Jr., Robert W. Birmingham and the Long Black Freedom Struggle. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.