Democratic Party in Alabama

Vivian Figures

The Alabama Democratic Party has existed for almost as long as Alabama has been a state. It was the strongest party within Alabama for most of the state’s history. During the roughly 50-year existence of the “solid, one-party South,” the Democratic Party was the political party of Alabama. In recent decades, a more competitive, two-party politics has emerged, lessening Democratic Party dominance in Alabama politics. Still, roughly 30 to 40 percent of Alabamians currently identify themselves as Democrats and hundreds of party members hold elected office at all levels of government throughout the state. During its history, the Alabama Democratic Party has experienced varying levels of internal division. The policy positions it has taken and the interests it has promoted have changed. The social, economic, and racial characteristics of its supporters have shifted, and Its level of electoral success has varied. What has remained constant, however, is the central and important position the Alabama Democratic Party occupies in the state’s politics.

Vivian Figures

The Alabama Democratic Party has existed for almost as long as Alabama has been a state. It was the strongest party within Alabama for most of the state’s history. During the roughly 50-year existence of the “solid, one-party South,” the Democratic Party was the political party of Alabama. In recent decades, a more competitive, two-party politics has emerged, lessening Democratic Party dominance in Alabama politics. Still, roughly 30 to 40 percent of Alabamians currently identify themselves as Democrats and hundreds of party members hold elected office at all levels of government throughout the state. During its history, the Alabama Democratic Party has experienced varying levels of internal division. The policy positions it has taken and the interests it has promoted have changed. The social, economic, and racial characteristics of its supporters have shifted, and Its level of electoral success has varied. What has remained constant, however, is the central and important position the Alabama Democratic Party occupies in the state’s politics.

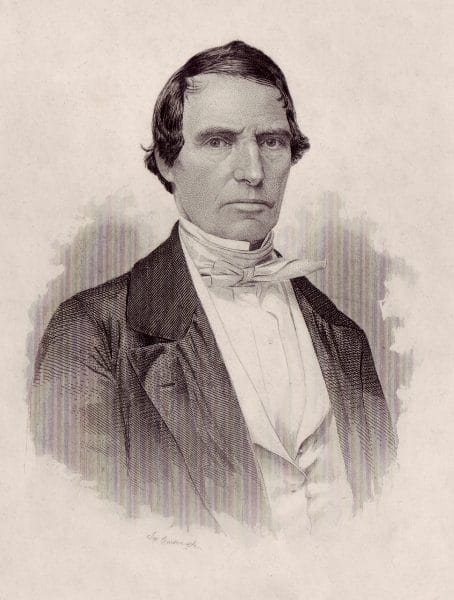

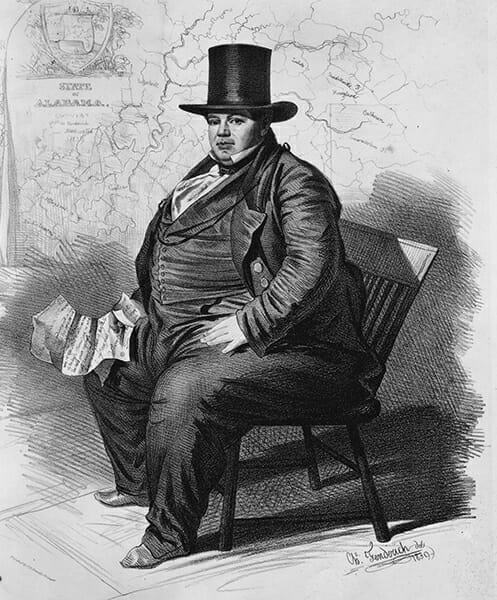

Statehood to Secession

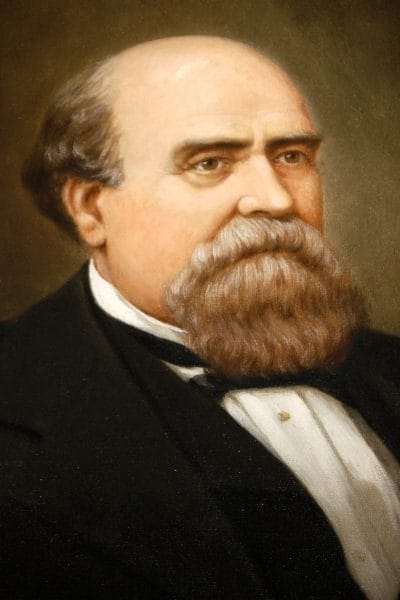

William Rufus King

As a formal organization, Alabama’s Democratic Party, first known as the Democratic-Republican Party, initially appeared in the state during the 1830s. The more informal roots of the party can be traced to pre-statehood political leaders and groups. During its early years, the party—under the leadership of figures such as U.S. senator and future vice president William Rufus King, Gov. John Gayle, U.S. representative and later senator Dixon Hall Lewis, and U.S. representative and newspaper editor William Lownes Yancey—experienced frequent splits, divisions, and reconfigurations. Similarly, the “opposition” also changed frequently, with the Whigs being the Democrats’ most consistent opponent prior to the Civil War. Between 1820 and 1860, the Democratic Party often faced stiff opposition but still carried the state in each pre-Civil War election for governor and president. In the 1845 contest for governor and the 1860 presidential race, however, splits within the party resulted in an “independent” Democrat winning over the “regular” Democratic candidate.

William Rufus King

As a formal organization, Alabama’s Democratic Party, first known as the Democratic-Republican Party, initially appeared in the state during the 1830s. The more informal roots of the party can be traced to pre-statehood political leaders and groups. During its early years, the party—under the leadership of figures such as U.S. senator and future vice president William Rufus King, Gov. John Gayle, U.S. representative and later senator Dixon Hall Lewis, and U.S. representative and newspaper editor William Lownes Yancey—experienced frequent splits, divisions, and reconfigurations. Similarly, the “opposition” also changed frequently, with the Whigs being the Democrats’ most consistent opponent prior to the Civil War. Between 1820 and 1860, the Democratic Party often faced stiff opposition but still carried the state in each pre-Civil War election for governor and president. In the 1845 contest for governor and the 1860 presidential race, however, splits within the party resulted in an “independent” Democrat winning over the “regular” Democratic candidate.

Dixon Hall Lewis

Prior to the Civil War, there was considerable overlap, as there is today, between Democrats and their opponents in terms of social and geographic characteristics. Generally, farmers and merchants living in the northern part of the state were the strongest Democratic supporters. The opposition mainly consisted of city residents and wealthy plantation owners and their business allies in the Black Belt, other sections of south Alabama, and parts of the Tennessee Valley. There was also substantial overlap in issue opinions between Democrats and their opposition in the pre-Civil War years. Democrats generally saw themselves as supporters of small farmers, merchants, and laborers who were concerned with maintaining individual rights and opposing strong centralized government. Their opponents tended to have a broader world view, were supportive of a stronger central government, and favored efforts to promote economic development.

Dixon Hall Lewis

Prior to the Civil War, there was considerable overlap, as there is today, between Democrats and their opponents in terms of social and geographic characteristics. Generally, farmers and merchants living in the northern part of the state were the strongest Democratic supporters. The opposition mainly consisted of city residents and wealthy plantation owners and their business allies in the Black Belt, other sections of south Alabama, and parts of the Tennessee Valley. There was also substantial overlap in issue opinions between Democrats and their opposition in the pre-Civil War years. Democrats generally saw themselves as supporters of small farmers, merchants, and laborers who were concerned with maintaining individual rights and opposing strong centralized government. Their opponents tended to have a broader world view, were supportive of a stronger central government, and favored efforts to promote economic development.

During the pre-Civil War years, Alabama Democrats fought amongst themselves and with their opponents over a wide range of issues, including the national bank, tariffs, the distribution of former Indian lands, and prohibition. The issues of slavery and secession grew in importance during this period, aided by national events, fears about the intentions of the national government, concerns about the economic impact of ending slavery, racial unity, and a weakened Whig Party. Eventually, these issues fractured both the Alabama Democratic Party and the state’s politics generally. This disintegration, in turn, hastened the move toward secession and civil war.

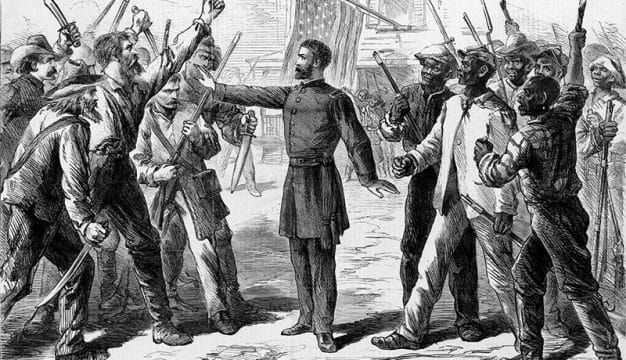

Reconstruction, Redemption, and Populism

George S. Houston

With Reconstruction, a larger number of freed blacks entered the state’s electorate and began voting for the antislavery Republican Party. The Democratic Party consequently no longer dominated Alabama’s politics. Instead, Republicans, including black party members, were repeatedly elected to a wide variety of public offices in the post-war years. Meanwhile, the state’s traditional, conservative Democratic leadership fought to regain political power. They appealed to white voters on the basis of racial unity. They took advantage of divisions among Alabama Republicans and a decreased interest in southern affairs among national Republicans. Party leaders also used fraud, intimidation, and violence to promote the party’s interests. These efforts finally succeeded in the election of 1874, when Democrat George Smith Houston defeated incumbent Republican governor David P. Lewis, beginning nearly 100 years of Democratic control over Alabama. Still, for another decade or more, African Americans remained a large component of the Alabama electorate and, while weakened, Republicans retained considerable support.

George S. Houston

With Reconstruction, a larger number of freed blacks entered the state’s electorate and began voting for the antislavery Republican Party. The Democratic Party consequently no longer dominated Alabama’s politics. Instead, Republicans, including black party members, were repeatedly elected to a wide variety of public offices in the post-war years. Meanwhile, the state’s traditional, conservative Democratic leadership fought to regain political power. They appealed to white voters on the basis of racial unity. They took advantage of divisions among Alabama Republicans and a decreased interest in southern affairs among national Republicans. Party leaders also used fraud, intimidation, and violence to promote the party’s interests. These efforts finally succeeded in the election of 1874, when Democrat George Smith Houston defeated incumbent Republican governor David P. Lewis, beginning nearly 100 years of Democratic control over Alabama. Still, for another decade or more, African Americans remained a large component of the Alabama electorate and, while weakened, Republicans retained considerable support.

Following the Reconstruction era, many issues, such as railroad regulations, taxation, and government reform, deeply divided Alabamians. There were also several serious challenges to Democratic rule from third-party and independent political movements. The most significant of these challenges occurred in the late nineteenth century, mainly over economic issues. This challenge, centered among the state’s small farmers, merchants, and laborers, first produced contests within the Democratic Party. When these efforts failed, the dissenters, under the leadership of gubernatorial candidate Reuben Kolb, joined with the Populist Party and “fused” their forces with the state’s Republicans, both black and white. Ultimately, through deal-making, fraud, and improved economic conditions, the party’s traditional leadership split this biracial coalition and defeated its Populist Party opponents.

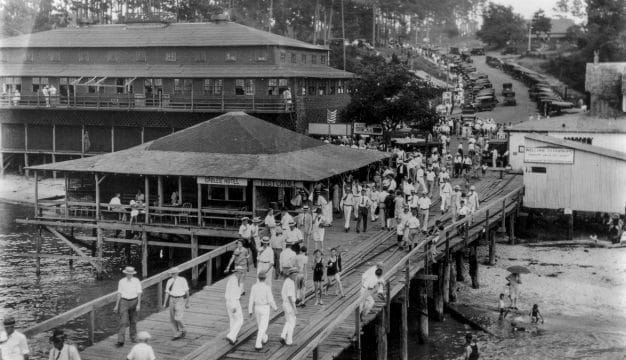

The Solid Democratic South

Following the demise of the Populist challenge, Alabama’s Black Belt political leaders and their urban-based financial and industrial allies, known later as the “Big Mules,” moved, like their counterparts in other southern states, to create a political system in which their power was secure. One major component of this system was turning Alabama into a one-party, solidly Democratic state. The development of one-party politics helped contain and control political divisions within the state and region. One-party politics also allowed the South to send a unified voting bloc to the U.S. Congress, thus reducing the likelihood of the national government interfering in southern affairs.

The goal of making Alabama a one-party Democratic state was aided by rewriting the state’s constitution in 1901 to implement a poll tax and literacy tests as requirements for voting, both aimed at disfranchising blacks and poor whites. The Democratic Party also began using another important disfranchising provision, ruling that only whites could vote in its primary elections. The political effect of these requirements was a smaller and more Democratic electorate. About 195,000 Alabamians, for example, voted in the 1896 presidential election. In contrast, only about 109,000 of the state’s citizens voted in the 1904 presidential contest.

Other considerations also helped in the development of one-party Democratic politics. Party leaders and candidates frequently told voters that the continuance of white supremacy required support for the Democratic Party. Indeed, a “white supremacy” slogan appeared on the Democratic Party’s election ballot until 1966. Further, because the party won all statewide and most local elections, qualified and politically ambitious potential candidates almost always chose to run on the Democratic ticket. With a near monopoly on the best candidates, Democrats continued to win in Alabama. The party also implemented a “sore loser” law that prohibited disgruntled primary election losers from re-entering an election contest as independents or as candidates for another party. Additionally, the party had a symbolically important, though probably unenforceable, “loyalty pledge” (which still appears on Democratic primary election ballots) committing those who participate in the primary election to support the party’s candidates in the general election.

Despite these provisions, practices, and requirements, the Republican Party did maintain a presence in the state during the early twentieth century. Although many black Alabamians were disfranchised, they generally remained loyal to the Republican Party. There were also significant pockets of white Republicans, especially in northern Alabama. The onset of the Great Depression and the popularity of Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal programs in the 1930s, however, greatly reduced Republican strength within the state.

Alfred E. Smith

During the era of the Solid South, Democratic candidates regularly won elections—usually by large margins and often without serious opposition—for all types of political offices at all levels of government. Only rarely during this period was Democratic dominance challenged. One such instance occurred in 1928, when Al Smith won the party’s presidential nomination. Because Smith was a Catholic, opposed prohibition, and was tied to the alleged corruption of New York’s Tammany Hall political machine, some Alabama Democrats refused to support the national party’s nominee. A few even said that they would vote for the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover. After a hard-fought campaign, Smith won in Alabama but by a margin far closer than in previous years. Later, some of the leading anti-Smith activists, such as U.S. Senator Tom Heflin, were “purged” from the party.

Alfred E. Smith

During the era of the Solid South, Democratic candidates regularly won elections—usually by large margins and often without serious opposition—for all types of political offices at all levels of government. Only rarely during this period was Democratic dominance challenged. One such instance occurred in 1928, when Al Smith won the party’s presidential nomination. Because Smith was a Catholic, opposed prohibition, and was tied to the alleged corruption of New York’s Tammany Hall political machine, some Alabama Democrats refused to support the national party’s nominee. A few even said that they would vote for the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover. After a hard-fought campaign, Smith won in Alabama but by a margin far closer than in previous years. Later, some of the leading anti-Smith activists, such as U.S. Senator Tom Heflin, were “purged” from the party.

Alabama’s one-party system meant that the “real” election in the state was the Democratic primary—whoever won it was sure to win the general election. Sometimes primary campaigns during this period involved relatively organized contests between candidates from the “progressive” and the “conservative” wings of the party. Progressives, who generally favored a more active government in terms of providing social services and were less concerned about race-related issues, received their greatest support from the northern counties and the Wiregrass region. The conservative wing of the party was composed of Black Belt politicians and their Big Mule financial and industrial allies found primarily in Birmingham and Mobile. When this progressive-conservative split did appear in the state’s Democratic politics, the more “liberal” wing of the party, represented by the likes of Gov. James E. Folsom Sr. and U.S. senators Lister Hill and John Sparkman, often won.

Most statewide Democratic primaries during this period, however, were not well structured. Instead, they often involved contests between numerous candidates, each supporting policies upon which everyone agreed. As a result, voters were often confused about which candidate to support. One indicator of this confusion was the occurrence of “friends-and-neighbors” voting, in which candidates received large majorities in their home county, and sometimes neighboring counties, but little support elsewhere. Because they had no other bases for casting their ballots, voters resorted to supporting the “home-town boy.”

Changing Electoral Politics

Many factors contributed to the end of the Democratic Party’s dominance in Alabama. The state’s shift from an agricultural to an industrial and service-based economy resulted in a more educated, wealthier, urban, less tradition-oriented, and altogether more politically diverse electorate. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the popularity of Pres. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs undermined support for the Republican Party among African Americans. At about the same time, the changes taking place in Alabama’s economy, along with greater job opportunities elsewhere, encouraged many blacks in Alabama and other southern states to move to the North and Midwest. Participants in this Great Migration often settled in large, politically competitive, and important states such as New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois. There, African Americans could vote and, because they were no longer sure Republican supporters, they became a critical “swing” segment of these states’ electorates. Also, both national and state public opinion shifted in the post-World War II and Cold War years in the direction of greater support for values such as equality, liberty, and freedom. This shift made it politically difficult to defend the practices of racial segregation and discrimination found in Alabama and other southern states.

The result of these economic, social, and political shifts was that, starting in the 1930s, the national Democratic Party, despite the opposition of some southern Democrats, began to take more liberal, proactive positions on a range of economic, labor, and social-service issues. The national Democratic Party also became increasingly sensitive to civil rights issues, again despite the opposition of some of its white southern supporters in Alabama and elsewhere in the South.

1948 Democratic National Convention

Dissatisfaction among some southerners with the national Democratic organization’s new policy positions soon split the party. When the party adopted a “liberal” civil rights plank at the 1948 national convention, half of the Alabama delegation, along with the entire Mississippi delegation, left the convention and, along with representatives from other states, reconvened in Birmingham and formed the States’ Rights (or Dixiecrat) Party. Their goal was to prevent either Pres. Harry S. Truman or his Republican opponent, Thomas Dewey, from winning a majority of Electoral College votes, thus leaving the decision-making for the presidential election to the House of Representatives. There, the Dixiecrats hoped that southerners could negotiate a deal that would preserve the region’s established racial and economic patterns. South Carolina’s governor Strom Thurmond was the Dixiecrats’ presidential candidate, but in Alabama he appeared on the ballot as the Democratic candidate. Thurmond easily won the state, but the Dixiecrats failed to stop Truman’s reelection. A struggle between States’ Righters and national-party loyalists over control of the Alabama Democratic Party would continue for several decades.

1948 Democratic National Convention

Dissatisfaction among some southerners with the national Democratic organization’s new policy positions soon split the party. When the party adopted a “liberal” civil rights plank at the 1948 national convention, half of the Alabama delegation, along with the entire Mississippi delegation, left the convention and, along with representatives from other states, reconvened in Birmingham and formed the States’ Rights (or Dixiecrat) Party. Their goal was to prevent either Pres. Harry S. Truman or his Republican opponent, Thomas Dewey, from winning a majority of Electoral College votes, thus leaving the decision-making for the presidential election to the House of Representatives. There, the Dixiecrats hoped that southerners could negotiate a deal that would preserve the region’s established racial and economic patterns. South Carolina’s governor Strom Thurmond was the Dixiecrats’ presidential candidate, but in Alabama he appeared on the ballot as the Democratic candidate. Thurmond easily won the state, but the Dixiecrats failed to stop Truman’s reelection. A struggle between States’ Righters and national-party loyalists over control of the Alabama Democratic Party would continue for several decades.

The 1948 States’ Rights campaign did undermine Alabamians’ unquestioned support for the Democratic Party. At the same time, the shifting policy positions of the national parties and the state’s changing economy generated new support among Alabamians for the Republican Party. Even though Democrats still carried Alabama in the 1952, 1956, and 1960 presidential elections, Republican strength was much greater than in previous years.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the civil rights movement pressured both national political parties to take a position supporting an end to racial segregation and discrimination. Partially as a result of events such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the Freedom Rides, and the demonstrations in Birmingham, the national Democratic Party, particularly under the leadership of Lyndon Johnson, became the most “liberal” party in terms of civil rights. Johnson’s Great Society programs also moved the national party in a more liberal direction in a number of other policy areas. With the nomination of conservative Arizona U.S. senator Barry Goldwater in the 1964 presidential campaign, the national Republican Party moved in the opposite direction on civil rights and other issues.

Goldwater lost badly to Johnson in the nation as a whole. In Alabama, however, he received almost 70 percent of the vote, thus becoming the first Republican to carry the state since 1872. That same year, Alabama Republicans also won, for the first time in almost a century, several of the state’s congressional seats. Republican success in Alabama’s presidential elections has continued. Since 1964, only one Democratic presidential candidate, Jimmy Carter in 1976, has carried Alabama. This string of Republican victories means that Alabama is now mostly ignored in presidential campaigns. Democratic candidates, knowing that they are unlikely to win in Alabama, make little effort to campaign here. Meanwhile, with victory assured in Alabama, Republican presidential candidates spend their campaign resources elsewhere.

The Wallace Era

George C. Wallace

Alabama’s Democrats continued to control Alabama’s state government through the mid-1980s, in part because of the long political career of George Wallace. One of the important events of Wallace’s first term as governor was the voting-rights demonstrations and marches held in Selma. Images of Alabama state troopers attacking civil rights marchers on the city’s Edmund Pettus Bridge contributed to the passage of the federal 1965 Voting Rights Act. This law removed many of the barriers to voting in Alabama and other states, resulting in a substantial increase in the state’s electorate. Numerically, more whites than blacks were added to the state’s voting rolls, but in percentage terms, the greatest impact occurred among African Americans. An estimated 23 percent of Alabama’s black citizens were registered to vote in 1964, but by 1966 that number had more than doubled to 51 percent. That year, Birmingham lawyer and future Alabama circuit court judge Robert Smith Vance became chair of the party and oversaw even more recruiting of Black members.

George C. Wallace

Alabama’s Democrats continued to control Alabama’s state government through the mid-1980s, in part because of the long political career of George Wallace. One of the important events of Wallace’s first term as governor was the voting-rights demonstrations and marches held in Selma. Images of Alabama state troopers attacking civil rights marchers on the city’s Edmund Pettus Bridge contributed to the passage of the federal 1965 Voting Rights Act. This law removed many of the barriers to voting in Alabama and other states, resulting in a substantial increase in the state’s electorate. Numerically, more whites than blacks were added to the state’s voting rolls, but in percentage terms, the greatest impact occurred among African Americans. An estimated 23 percent of Alabama’s black citizens were registered to vote in 1964, but by 1966 that number had more than doubled to 51 percent. That year, Birmingham lawyer and future Alabama circuit court judge Robert Smith Vance became chair of the party and oversaw even more recruiting of Black members.

During his career, Wallace appealed to voters on many, and sometimes shifting, grounds. Early in his career, Wallace promised the state’s mostly white electorate that he would maintain “segregation forever.” In his last campaign in 1982, he echoed the mantra of the civil rights movement by telling the state’s now more racially diverse electorate “we shall overcome.” The scope of Wallace’s appeal to voters kept much of Alabama’s political disagreements contained within the Democratic Party, thus inhibiting the involvement of the state’s Republicans. Still, the Republican Party did increase its strength within Alabama’s state-level politics. Jeremiah Denton, for example, became Alabama’s first Republican U.S. senator since Reconstruction.

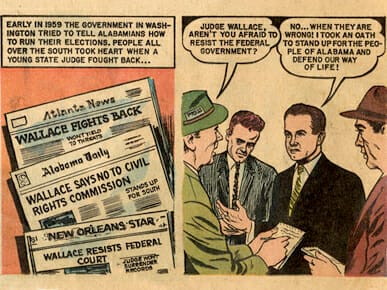

George Wallace Campaign Comic

When Wallace announced his political retirement in 1986, a bitter struggle began for the Democratic nomination for governor. In a runoff contest, Attorney General Charles Graddick defeated Lt. Gov. Bill Baxley. But Graddick was denied the nomination because a federal court found that he had violated the provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that requires prior approval of the U.S. Justice Department or the federal courts in Washington, D.C., before changing election regulations. In his place, a party committee named Baxley as its nominee, rather than calling for a new primary election. Public anger over this seemingly undemocratic decision led to the election of Guy Hunt, the first Republican governor of Alabama since Reconstruction.

George Wallace Campaign Comic

When Wallace announced his political retirement in 1986, a bitter struggle began for the Democratic nomination for governor. In a runoff contest, Attorney General Charles Graddick defeated Lt. Gov. Bill Baxley. But Graddick was denied the nomination because a federal court found that he had violated the provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that requires prior approval of the U.S. Justice Department or the federal courts in Washington, D.C., before changing election regulations. In his place, a party committee named Baxley as its nominee, rather than calling for a new primary election. Public anger over this seemingly undemocratic decision led to the election of Guy Hunt, the first Republican governor of Alabama since Reconstruction.

Contemporary Partisan Politics

Alabama’s Democratic Party is no longer the dominant party within Alabama and is now part of the state’s competitive, and increasingly Republican-leaning, party system. Current surveys show a roughly equal number of Democratic and Republican identifiers in the state. These studies also find that the state’s African American voters are overwhelmingly Democratic. Among white Alabamians, women and less-educated and lower-income voters are more likely than others to be Democrats.

Terri Sewell

Republican candidates have won all but one of the state’s elections for governor since 1986. Many of these recent contests, however, have been quite competitive. Alabama senator Richard Shelby is a Republican, but Shelby was first elected to the Senate in 1986 as a Democrat. Following the 1994 election, he switched to the Republican Party. In 1993, state senator Earl Hilliard became the first African American man elected as a Democrat to the U.S. Congress since Reconstruction. Since the 1990s, Republicans have held a majority of Alabama’s U.S. House seats. After the 2010 elections, the Alabama State Legislature came under Republican control for the first time in the state’s history. That year, however, Selma native Terri Sewell became the first African American woman to represent Alabama in the U.S. Congress. Former congressman Artur Davis ran unsuccessfully for governor in 2010, left the Democratic Party for the Republican Party, and then returned to the Democratic Party in 2016.

Terri Sewell

Republican candidates have won all but one of the state’s elections for governor since 1986. Many of these recent contests, however, have been quite competitive. Alabama senator Richard Shelby is a Republican, but Shelby was first elected to the Senate in 1986 as a Democrat. Following the 1994 election, he switched to the Republican Party. In 1993, state senator Earl Hilliard became the first African American man elected as a Democrat to the U.S. Congress since Reconstruction. Since the 1990s, Republicans have held a majority of Alabama’s U.S. House seats. After the 2010 elections, the Alabama State Legislature came under Republican control for the first time in the state’s history. That year, however, Selma native Terri Sewell became the first African American woman to represent Alabama in the U.S. Congress. Former congressman Artur Davis ran unsuccessfully for governor in 2010, left the Democratic Party for the Republican Party, and then returned to the Democratic Party in 2016.

Democrat and former federal prosecutor Doug Jones was elected in November 2017 to the Senate seat vacated by Republican Jeff Sessions, who joined the cabinet of Pres. Donald Trump as U.S. Attorney General. Jones was helped somewhat by running against the controversial former state Supreme Court chief justice Roy Moore, who was alleged to have behaved improperly toward underage teen girls. The party has been unable to otherwise mount serious challenges to Republican control of state and national offices, however. An exception is the Seventh Congressional District, which has been in Democratic hands since 1967. In the run-up to the 2020 elections, the Democratic National Committee has criticized the state party for lacking diversity in its leadership and had also threatened to forbid Alabama delegates to sit at the 2020 Democratic National Convention as factions battle for control of the party.

Don Siegelman, 1999

Surveys of current party officials show relatively little difference between Alabama Democratic and Republican party activists in terms of education, income, or age. As a group, Democratic activists are more likely to be African Americans and women than are Republicans. Most local Democratic Party officials in Alabama now describe their political beliefs as “very” or “somewhat” liberal, although there are considerable numbers of moderates. In contrast, a majority of local Republican Party officials in Alabama say that they are “very conservative.” As an organization, the current Alabama Democratic Party is not particularly close-knit or active. In recent years, however, the party’s resources, internal unity, and activity level has increased.

Don Siegelman, 1999

Surveys of current party officials show relatively little difference between Alabama Democratic and Republican party activists in terms of education, income, or age. As a group, Democratic activists are more likely to be African Americans and women than are Republicans. Most local Democratic Party officials in Alabama now describe their political beliefs as “very” or “somewhat” liberal, although there are considerable numbers of moderates. In contrast, a majority of local Republican Party officials in Alabama say that they are “very conservative.” As an organization, the current Alabama Democratic Party is not particularly close-knit or active. In recent years, however, the party’s resources, internal unity, and activity level has increased.