Birmingham Campaign of 1963

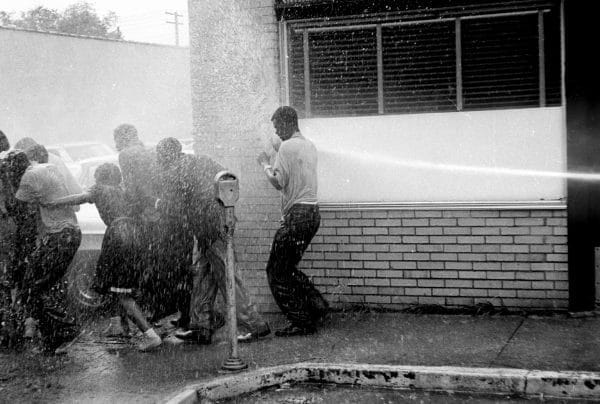

Police Water Cannon Attack

The climax of the modern civil rights movement occurred in Birmingham. The city’s violent response to the spring 1963 demonstrations against white supremacy forced the federal government to intervene on behalf of race reform. City Commissioner T. Eugene “Bull” Connor‘s use of police dogs and fire hoses against nonviolent black activists, led by Fred L. Shuttlesworth, Ralph Abernathy, and Martin Luther King Jr., enraged the nation. The public outcry provoked Pres. John F. Kennedy to propose civil rights legislation that became the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act opened America’s social, economic, and political system to African Americans and other minorities, including women, the disabled, and gays and lesbians. The legislation addressed the principal goal of the movement of gaining access to the system as consumers but also set in motion strategies to gain equality through affirmative action policies.

Police Water Cannon Attack

The climax of the modern civil rights movement occurred in Birmingham. The city’s violent response to the spring 1963 demonstrations against white supremacy forced the federal government to intervene on behalf of race reform. City Commissioner T. Eugene “Bull” Connor‘s use of police dogs and fire hoses against nonviolent black activists, led by Fred L. Shuttlesworth, Ralph Abernathy, and Martin Luther King Jr., enraged the nation. The public outcry provoked Pres. John F. Kennedy to propose civil rights legislation that became the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act opened America’s social, economic, and political system to African Americans and other minorities, including women, the disabled, and gays and lesbians. The legislation addressed the principal goal of the movement of gaining access to the system as consumers but also set in motion strategies to gain equality through affirmative action policies.

Shuttlesworth Home Bombed

Having witnessed the organization of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Shuttlesworth organized his own group, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), in June 1956 after the state outlawed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In December 1956, when the federal courts ordered the desegregation of Montgomery’s buses, Shuttlesworth asked the officials of Birmingham’s transit system to end segregated seating, setting a December 26 deadline. He intended to challenge the laws on a bus on that day, but on the night of December 25, Klansmen bombed Bethel Baptist Church and parsonage, nearly assassinating Shuttlesworth. He emerged out of the rubble of his dynamited house and led a protest the next morning that resulted in a legal case against the city’s segregation ordinance. Coinciding with school desegregation in Little Rock, Arkansas, Shuttlesworth arranged a challenge to Birmingham’s all-white Phillips High School in September 1957, nearly suffering death at the hands of an angry mob. Segregationist vigilantes again greeted Shuttlesworth when he desegregated the train station. In 1958, Shuttlesworth organized a boycott of Birmingham’s buses in support of the ACMHR legal case against segregated seating. Shuttlesworth’s aggressive strategy of direct action alienated him from Birmingham’s established black leadership. Many people in the black middle class found as too extreme the intense religious belief held by ACMHR members that God was going to end segregation.

Shuttlesworth Home Bombed

Having witnessed the organization of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Shuttlesworth organized his own group, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), in June 1956 after the state outlawed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In December 1956, when the federal courts ordered the desegregation of Montgomery’s buses, Shuttlesworth asked the officials of Birmingham’s transit system to end segregated seating, setting a December 26 deadline. He intended to challenge the laws on a bus on that day, but on the night of December 25, Klansmen bombed Bethel Baptist Church and parsonage, nearly assassinating Shuttlesworth. He emerged out of the rubble of his dynamited house and led a protest the next morning that resulted in a legal case against the city’s segregation ordinance. Coinciding with school desegregation in Little Rock, Arkansas, Shuttlesworth arranged a challenge to Birmingham’s all-white Phillips High School in September 1957, nearly suffering death at the hands of an angry mob. Segregationist vigilantes again greeted Shuttlesworth when he desegregated the train station. In 1958, Shuttlesworth organized a boycott of Birmingham’s buses in support of the ACMHR legal case against segregated seating. Shuttlesworth’s aggressive strategy of direct action alienated him from Birmingham’s established black leadership. Many people in the black middle class found as too extreme the intense religious belief held by ACMHR members that God was going to end segregation.

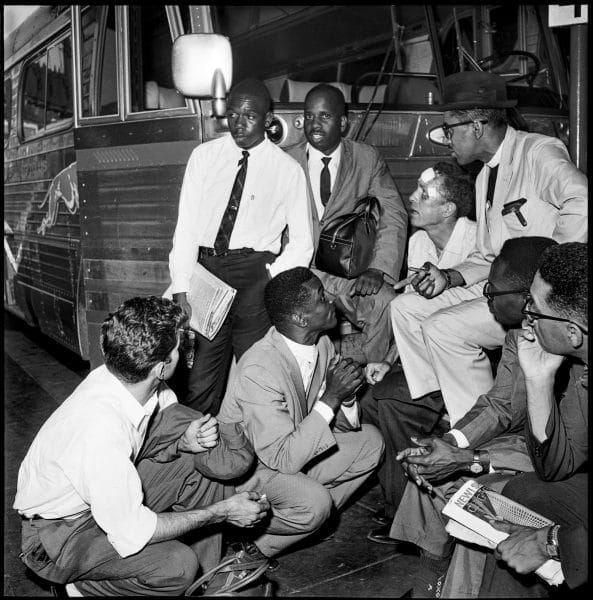

Fred Shuttlesworth and Freedom Riders

Prompted by the national sit-in movement begun by four black college men in Greensboro, North Carolina, in February 1960, a group of black students in Birmingham from Miles College and Daniel Payne College held a prayer vigil. Shuttlesworth and the ACMHR supported their efforts. When a national group of black and white demonstrators undertook the Freedom Rides in May 1961, Shuttlesworth and the ACMHR provided assistance, rescuing the stranded protesters outside Anniston as well as those who suffered a Klan attack at the Birmingham Trailways Station. In spring 1962, Birmingham’s black college students initiated the Selective Buying Campaign and, with support from Shuttlesworth and ACMHR, it became the catalyst for the spring 1963 demonstrations.

Fred Shuttlesworth and Freedom Riders

Prompted by the national sit-in movement begun by four black college men in Greensboro, North Carolina, in February 1960, a group of black students in Birmingham from Miles College and Daniel Payne College held a prayer vigil. Shuttlesworth and the ACMHR supported their efforts. When a national group of black and white demonstrators undertook the Freedom Rides in May 1961, Shuttlesworth and the ACMHR provided assistance, rescuing the stranded protesters outside Anniston as well as those who suffered a Klan attack at the Birmingham Trailways Station. In spring 1962, Birmingham’s black college students initiated the Selective Buying Campaign and, with support from Shuttlesworth and ACMHR, it became the catalyst for the spring 1963 demonstrations.

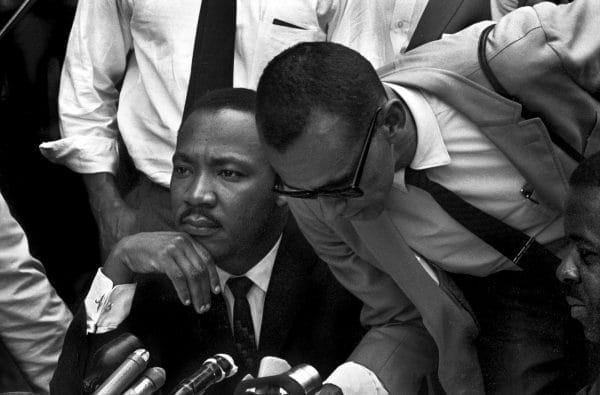

Chosen as secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) when it organized in 1957, Shutttlesworth had been an active member of the region’s leading civil rights group. But he was frustrated because he believed that the SCLC lacked clear direction under King’s leadership. Shuttlesworth watched the SCLC intervene in Albany, Georgia, in 1961 and fail to successfully challenge segregation in a manner that forced reforms in local race relations. Aware that King’s reputation had suffered from this defeat, Shuttlesworth invited the SCLC to assist him and the ACMHR in Birmingham. Believing that a success would restore his reputation as a national civil rights leader, King agreed. Shuttlesworth hoped King’s prestige would attract the black masses and thus mobilize Birmingham’s black community behind the joint ACMHR-SCLC campaign.

“Bull” Connor in 1963

Leaders from the ACMHR met with SCLC officials to plan strategy. Having learned from prior mistakes, King’s lieutenant, the Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker, proposed a limited campaign of sit-ins and pickets designed to pressure merchants and local business leaders into demanding the city commission repeal the municipal segregation ordinances. Some scholars have argued that the strategy called for violent confrontations with Bull Connor leading to mass arrests that would force the Kennedy Administration to intervene on behalf of civil rights, but this was not the case. The tactic of filling the jail had failed to alter race relations in Albany, and the noncommittal Kennedy Administration had yet to offer support for the movement and in fact had aided the segregationists. Indeed, the best ACMHR-SCLC could hope to achieve was some modicum of change in local race relations that might point the way toward regional reform of the South’s segregated social structure.

“Bull” Connor in 1963

Leaders from the ACMHR met with SCLC officials to plan strategy. Having learned from prior mistakes, King’s lieutenant, the Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker, proposed a limited campaign of sit-ins and pickets designed to pressure merchants and local business leaders into demanding the city commission repeal the municipal segregation ordinances. Some scholars have argued that the strategy called for violent confrontations with Bull Connor leading to mass arrests that would force the Kennedy Administration to intervene on behalf of civil rights, but this was not the case. The tactic of filling the jail had failed to alter race relations in Albany, and the noncommittal Kennedy Administration had yet to offer support for the movement and in fact had aided the segregationists. Indeed, the best ACMHR-SCLC could hope to achieve was some modicum of change in local race relations that might point the way toward regional reform of the South’s segregated social structure.

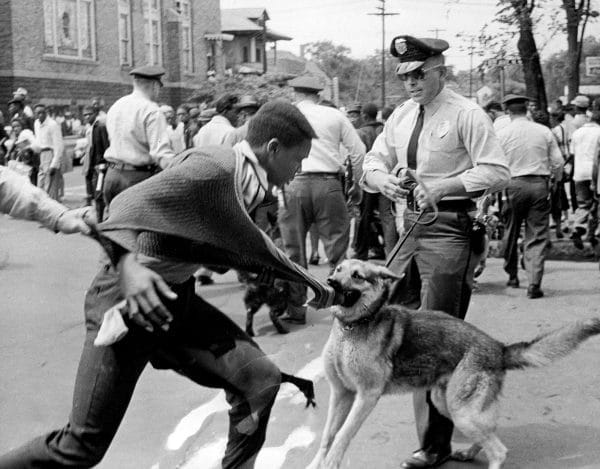

Police Dog Attack

The joint ACMHR-SCLC Birmingham campaign began quietly with sit-ins on April 3, 1963, at several downtown “whites-only” lunch counters. From the outset, the campaign confronted an apathetic black community, an openly hostile established black leadership, and Bull Connor’s “nonviolent resistance” in the form of polite arrests of the offenders of the city’s segregation ordinances. With no sensational news, the national media found nothing to report, and the campaign floundered. But when Connor ordered out police dogs to disperse a crowd of black bystanders, journalists recorded the attack of a German shepherd on a nonviolent protester, thereby revealing the brutality that underpinned segregation. The episode convinced Walker and King to use direct-action tactics to generate creative tension for the sake of media coverage. The ease with which the campaign changed directions reflected the fluidity of the movement. Shuttlesworth led the first of many protest marches on City Hall to emphasize the refusal of the city commission to issue parade permits to the protestors.

Police Dog Attack

The joint ACMHR-SCLC Birmingham campaign began quietly with sit-ins on April 3, 1963, at several downtown “whites-only” lunch counters. From the outset, the campaign confronted an apathetic black community, an openly hostile established black leadership, and Bull Connor’s “nonviolent resistance” in the form of polite arrests of the offenders of the city’s segregation ordinances. With no sensational news, the national media found nothing to report, and the campaign floundered. But when Connor ordered out police dogs to disperse a crowd of black bystanders, journalists recorded the attack of a German shepherd on a nonviolent protester, thereby revealing the brutality that underpinned segregation. The episode convinced Walker and King to use direct-action tactics to generate creative tension for the sake of media coverage. The ease with which the campaign changed directions reflected the fluidity of the movement. Shuttlesworth led the first of many protest marches on City Hall to emphasize the refusal of the city commission to issue parade permits to the protestors.

Good Friday March

As the number of demonstrations increased, police arrested more ACMHR members, consequently draining the financial resources of the campaign. Black bystanders gave the campaign the appearance of mass support, but the vast majority of Birmingham’s black residents remained uninvolved. A more serious threat came from established black leaders who opposed the civil rights campaign and actively worked to undermine Shuttlesworth by negotiating with the white power structure. Although King’s decision to seek arrest marked a turning point in his life as a leader, it did little to increase support for the faltering ACMHR-SCLC campaign. From behind bars, he penned the “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” which became the clearest statement on the righteousness of civil rights protest. But after a month of exhaustive demonstrations, the stalemate with white authorities suggested another Albany and the looming defeat of the Birmingham Campaign.

Good Friday March

As the number of demonstrations increased, police arrested more ACMHR members, consequently draining the financial resources of the campaign. Black bystanders gave the campaign the appearance of mass support, but the vast majority of Birmingham’s black residents remained uninvolved. A more serious threat came from established black leaders who opposed the civil rights campaign and actively worked to undermine Shuttlesworth by negotiating with the white power structure. Although King’s decision to seek arrest marked a turning point in his life as a leader, it did little to increase support for the faltering ACMHR-SCLC campaign. From behind bars, he penned the “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” which became the clearest statement on the righteousness of civil rights protest. But after a month of exhaustive demonstrations, the stalemate with white authorities suggested another Albany and the looming defeat of the Birmingham Campaign.

Birmingham Campaign Demonstrators

In a desperate bid to generate media coverage and to keep the campaign alive, King’s lieutenants launched the Children’s Crusade on May 2, 1963, in which black youth from area schools served as demonstrators. Trying to avoid the use of force, Bull Connor arrested hundreds of school children and hauled them off to jail on school buses. When the jails were filled, he called out fire hoses and police dogs to contain large protests in the black business district along the city’s Kelly Ingram Park. African American spectators responded with outrage, pelting police with bricks and bottles as firemen opened up the hoses on not just the nonviolent youngsters but also on enraged black bystanders who had nearly begun a riot. The media captured the negative images of Connor and his men suppressing the nonviolent protest of school children with brutal blasts from water cannons and attacks from police dogs. Front-page photographs in the nation’s newspapers convinced Kennedy to send Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Burke Marshall to Birmingham to secure negotiations that would end the violent demonstrations. Previous federal policy regarding civil rights issues had left enforcement to local law and order officials without direct intervention by the national government. At first, Marshall succeeded in fashioning a similar resolution by convincing King to call off the protests without winning any real concessions from the local white power structure. Shuttlesworth held out for more concrete results, and his opposition led to a re-evaluation of the terms for an ultimate truce that announced limited local race reforms.

Birmingham Campaign Demonstrators

In a desperate bid to generate media coverage and to keep the campaign alive, King’s lieutenants launched the Children’s Crusade on May 2, 1963, in which black youth from area schools served as demonstrators. Trying to avoid the use of force, Bull Connor arrested hundreds of school children and hauled them off to jail on school buses. When the jails were filled, he called out fire hoses and police dogs to contain large protests in the black business district along the city’s Kelly Ingram Park. African American spectators responded with outrage, pelting police with bricks and bottles as firemen opened up the hoses on not just the nonviolent youngsters but also on enraged black bystanders who had nearly begun a riot. The media captured the negative images of Connor and his men suppressing the nonviolent protest of school children with brutal blasts from water cannons and attacks from police dogs. Front-page photographs in the nation’s newspapers convinced Kennedy to send Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Burke Marshall to Birmingham to secure negotiations that would end the violent demonstrations. Previous federal policy regarding civil rights issues had left enforcement to local law and order officials without direct intervention by the national government. At first, Marshall succeeded in fashioning a similar resolution by convincing King to call off the protests without winning any real concessions from the local white power structure. Shuttlesworth held out for more concrete results, and his opposition led to a re-evaluation of the terms for an ultimate truce that announced limited local race reforms.

Desegregation Settlement Reached

The national media attention helped to spread the fervor of the ACMHR-SCLC Birmingham Campaign well beyond the city’s borders, and national demonstrations, international pressure, and inner city riots followed in the wake of the agreement. These actions convinced a reluctant Kennedy administration to propose sweeping reforms that Congress ultimately passed as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. With this legislation, the civil rights movement achieved its goals of gaining access to public accommodations and equal employment opportunities, thereby ending acquiescence to white supremacy and opening the system to African Americans and other minorities. In hindsight the moderate success of inclusion only expanded access and did not alter or challenge the class structure, thus leaving movement members with a wistful sense for the need for economic justice. In the years that followed, white resistance exaggerated the significance of the limited racial inclusion.

Desegregation Settlement Reached

The national media attention helped to spread the fervor of the ACMHR-SCLC Birmingham Campaign well beyond the city’s borders, and national demonstrations, international pressure, and inner city riots followed in the wake of the agreement. These actions convinced a reluctant Kennedy administration to propose sweeping reforms that Congress ultimately passed as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. With this legislation, the civil rights movement achieved its goals of gaining access to public accommodations and equal employment opportunities, thereby ending acquiescence to white supremacy and opening the system to African Americans and other minorities. In hindsight the moderate success of inclusion only expanded access and did not alter or challenge the class structure, thus leaving movement members with a wistful sense for the need for economic justice. In the years that followed, white resistance exaggerated the significance of the limited racial inclusion.

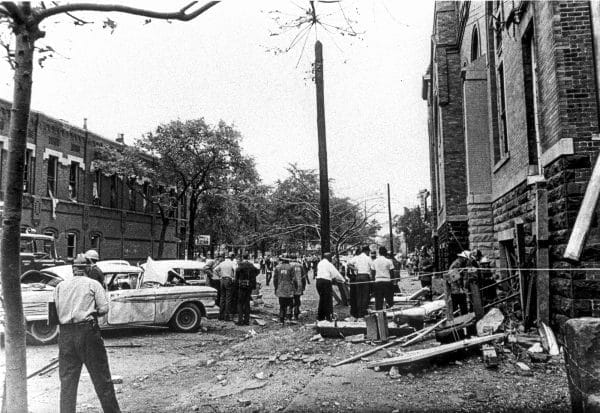

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing

White vigilantes attempted to scuttle the race reforms by bombing sites related to the civil rights struggle. When court-ordered school desegregation arrived in the city in September 1963, Klansmen bombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killing four black girls. Only with the implementation of the Civil Rights Act, adopted the next year, did the city completely desegregate, and then only following the U. S. Supreme Court’s ruling in the Heart of Atlanta Motel v. the United States case, which also involved Birmingham’s Ollie’s Barbecue. When Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965 many African Americans in Birmingham won the right to vote for the first time, foreshadowing a sea change in local politics. Although members of the black middle class and working class enjoyed access to the system, many African Americans remained shut out, having gained little from the reforms won in Birmingham. Nevertheless, the appointment of Arthur Shores to the city council in 1968 and the election of Richard Arrington as mayor in 1979 represented the strength of the growing black electorate and the success of black political empowerment that grew directly out of the Birmingham campaign.

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing

White vigilantes attempted to scuttle the race reforms by bombing sites related to the civil rights struggle. When court-ordered school desegregation arrived in the city in September 1963, Klansmen bombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killing four black girls. Only with the implementation of the Civil Rights Act, adopted the next year, did the city completely desegregate, and then only following the U. S. Supreme Court’s ruling in the Heart of Atlanta Motel v. the United States case, which also involved Birmingham’s Ollie’s Barbecue. When Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965 many African Americans in Birmingham won the right to vote for the first time, foreshadowing a sea change in local politics. Although members of the black middle class and working class enjoyed access to the system, many African Americans remained shut out, having gained little from the reforms won in Birmingham. Nevertheless, the appointment of Arthur Shores to the city council in 1968 and the election of Richard Arrington as mayor in 1979 represented the strength of the growing black electorate and the success of black political empowerment that grew directly out of the Birmingham campaign.

Further Reading

- Bass, S. Jonathan. Blessed Are the Peacemakers: Martin Luther King, Jr., Eight White Religious Leaders, and the “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001.

- Eskew, Glenn T. But For Birmingham: The Local and National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Garrow, David J. Birmingham, Alabama, 1956-1963: The Black Struggle for Civil Rights. Brooklyn. N.Y.: Carlson Publishing, 1989.

- Manis, Andrew M. A Fire You Can’t Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham’s Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

- Thornton, J. Mills, III. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.