Spanish West Florida

The Spanish colony of West Florida was a territory in the Southeast that spanned a large section of the central Gulf Coast. Organized in 1783, it represented the last European claim to any portion of the state of Alabama and at one time encompassed most of the southern half of the state. The United States acquired the colony in a piecemeal fashion between 1810 and 1819 through a combination of military force and diplomacy. Sections of the former West Florida were incorporated into the modern states of Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

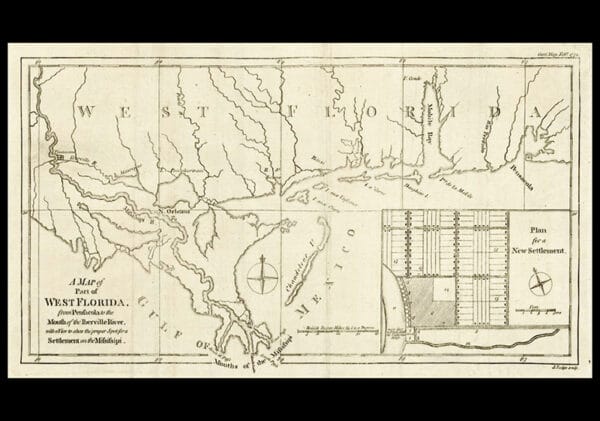

West Florida, 1772

The boundaries of the colony of Spanish West Florida trace back to the shifting power relations caused by the European Seven Years’ War (called the French and Indian War in colonial North America). The main antagonists were Great Britain and France, with Spain allied to the French, and aspects of the war played out in their colonial territories in North America. In the aftermath of the British victory and under the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris, France and Spain were forced to cede virtually all of their colonial territories in North America to Great Britain (although France held a small portion of the Louisiana Territory). Spain had been the first European power to control what is now Florida after Juan Ponce de León claimed it in 1513, but the Spanish government had not divided the territory into specific colonial departments and maintained little presence in the region.

West Florida, 1772

The boundaries of the colony of Spanish West Florida trace back to the shifting power relations caused by the European Seven Years’ War (called the French and Indian War in colonial North America). The main antagonists were Great Britain and France, with Spain allied to the French, and aspects of the war played out in their colonial territories in North America. In the aftermath of the British victory and under the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris, France and Spain were forced to cede virtually all of their colonial territories in North America to Great Britain (although France held a small portion of the Louisiana Territory). Spain had been the first European power to control what is now Florida after Juan Ponce de León claimed it in 1513, but the Spanish government had not divided the territory into specific colonial departments and maintained little presence in the region.

Bernardo de Gálvez

When the British took control of Florida, they divided the colony into western and eastern districts for administrative purposes, with British West Florida being bordered by the Mississippi River in the west and the Apalachicola River in the east. During the American Revolution, Spain, through the efforts of colonial governor Bernardo de Gálvez, sought to conquer the region, launching successful attacks on British outposts throughout West Florida led by his commander José Manuel de Ezpeleta. The most significant battles occurred at Baton Rouge (1779), Fort Charlotte in Mobile (1780), and Pensacola (1781). By the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which concluded the American Revolution, the Spanish were given possession of the colony. Spain essentially kept intact the borders established under the British, with the exception of its northern limit. Attempting to follow the precedent set by the British, the Spanish asserted that the territory’s northern boundary extended to the point where the Yazoo River emptied into the Mississippi, at latitude 32U+00BA28′. Their claim was later challenged by the United States and ultimately decided in the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo, which set the boundary more than 100 miles further south, at the 31st parallel.

Bernardo de Gálvez

When the British took control of Florida, they divided the colony into western and eastern districts for administrative purposes, with British West Florida being bordered by the Mississippi River in the west and the Apalachicola River in the east. During the American Revolution, Spain, through the efforts of colonial governor Bernardo de Gálvez, sought to conquer the region, launching successful attacks on British outposts throughout West Florida led by his commander José Manuel de Ezpeleta. The most significant battles occurred at Baton Rouge (1779), Fort Charlotte in Mobile (1780), and Pensacola (1781). By the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which concluded the American Revolution, the Spanish were given possession of the colony. Spain essentially kept intact the borders established under the British, with the exception of its northern limit. Attempting to follow the precedent set by the British, the Spanish asserted that the territory’s northern boundary extended to the point where the Yazoo River emptied into the Mississippi, at latitude 32U+00BA28′. Their claim was later challenged by the United States and ultimately decided in the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo, which set the boundary more than 100 miles further south, at the 31st parallel.

West Florida was sparsely settled during the Spanish period. Other than the relatively large city of Natchez (now in Mississippi), which lay in the contested area north of the final boundary, it contained only isolated settlements primarily clustered around the small communities of Pensacola, Mobile, and Baton Rouge. The majority of inhabitants in these enclaves were not Spanish but rather were recent immigrants from Great Britain as well as a significant number of American Tories who had fled seaboard British colonies during the Revolutionary War.

Spain’s official presence in the colony was even more limited, as its weak colonial government, headquartered in Pensacola, never had the resources to offer more than token administration of the struggling colony. Spain maintained small garrisons at fortifications in the colony’s key population centers and, for a brief period, at forts located north of the 31st parallel, including Fort Confederation near present-day Livingston, Sumter County; Fort San Esteban at St. Stephens, Washington County; and Fort Nogales at modern Vicksburg, Mississippi. These efforts proved entirely insufficient to defend the colony against American advances.

Americans in the region fervently believed that West Florida rightfully belonged to the United States by the terms of the Louisiana Purchase (1803), a view shared by federal officials in the nation’s capital, notably Pres. Thomas Jefferson and his successor, James Madison. Consequently, small groups of locals, some tacitly supported by federal officials, undertook efforts to subvert Spanish sovereignty in the region in the decade after the Purchase. The dispute was especially intense along the colony’s western border, in the area known as Feliciana in what is now Louisiana, where as early as 1804 efforts to liberate portions of the province or even annex it to the United States took place.

In 1810, a large organized group of American sympathizers living around Baton Rouge seized the Spanish post there and established the independent “Republic of West Florida.” The nascent “republic” sent commissioners to Mobile and Pensacola shortly afterward, hoping to encourage sympathizers in those communities to also rebel and send military forces against local Spanish authorities, or seize control of the entire colony. Little ultimately came of these actions, although malcontents north of Mobile did plan an insurgent expedition of their own. The small force of a few dozen men got as far as camping along the rivers north of the city but made no threat on its military command center of Fort Carlota (originally built by the French in 1723 as Fort Condé). In December of that year, rebels and Spanish authorities clashed north of Mobile on Saw Mill Creek, with reports of the incident indicating that four sympathizers and two Spaniards were killed. Seizing the opportunity presented by the upheaval, Pres. Madison quickly moved to proclaim control of that portion of West Florida in control of the rebels, stretching from the Mississippi River to the Pearl River, adding it to the U.S.-controlled Orleans Territory (the future state of Louisiana). He ordered Orleans territorial governor William C. C. Claiborne to occupy the region with his troops.

In acts passed by Congress in 1811 and 1812, the United States laid unofficial claim to the remainder of West Florida between the Pearl and Perdido Rivers, adding that section of the colony to official jurisdictions related to the Mississippi Territory (the future states of Mississippi and Alabama) and naming Mobile as the administrative center for the region. Territorial governor David Holmes even appointed government officials for the new addition. Spain viewed all of these actions as illegitimate, however, and continued to maintain a garrison in Mobile.

During the War of 1812, U.S. military forces finally moved to occupy the Mobile area by force, ostensibly to prevent the Spanish from using it to supply aid to the British. On April 12, 1813, U.S. general James Wilkinson arrived at the city with a large combined army and navy force and demanded the surrender of Fort Carlota. Severely outnumbered, its commander, Capt. Cayetano Pérez, did so without firing a shot the next day. With the departure of Mobile’s Spanish garrison, the United States at last formally took possession of the region between the Pearl and Perdido Rivers. The remainder of the original colony of West Florida, lying east of the Apalachicola River, later came under American control through the terms of the Adams-Onis Treaty (1819), which outlined the official cession of the entirety of Florida to the United States.

Further Reading

- Abernathy, Thomas P. The South in the New Nation, 1789-1819. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1976.

- Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

- Abernathy, Thomas P. The South in the New Nation, 1789-1819. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1976.

- Clark, Thomas D., and John D. W. Guice. The Old Southwest, 1795-1830: Frontiers in Conflict. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989.

- Davis, William C. The Rogue Republic: How Would-Be Patriots Waged the Shortest Revolution in American History. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.

- Haynes, Robert V. The Mississippi Territory and the Southwest Frontier, 1795-1817. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2010.

- McMichael, Andrew. Atlantic Loyalties: Americans in Spanish West Florida, 1785-1810. Athens: University of George Press, 2008.

- Owsley, Frank L., and Gene A. Smith. Filibusters and Expansionists: Jeffersonian Manifest Destiny, 1800-1821. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997.

- Thomason, Michael V. R., ed. Mobile: The New History of Alabama’s First City. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.