Public Education in Alabama After Desegregation

The end of segregated schools in the South, and in Alabama, was supposed to take place in 1954 with the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (347 U.S. 483). That ruling declared segregation in public education unconstitutional. Public education in Alabama, however, continued to be hampered for many years by racial segregation and chronic underfunding. The state had long struggled with these two issues, the legacy of strong conservative Democratic or “Redeemer” tendencies in Alabama state government that promoted low taxes and small budgets and resulted in a poorly financed and performing public school system. In more recent decades, efforts to improve school funding have been unsuccessful.

Resistance to Brown

Albert Boutwell

Before Brown v. Board, Alabama and other southern states had attempted to equalize school funding and teacher pay for blacks and whites while also passing laws designed to preserve segregation. Between the early 1940s and the early 1950s, pay for black teachers increased by almost 212 percent. Funding for students increased similarly. Even as attempts were made to equalize funding, the state worked harder to preserve segregation. Beginning in 1953, the state allowed local superintendents to place students in schools based on academic preparation. After the Brown decision, the state enacted legislation aimed at circumventing the ruling. A 1955 “pupil placement law,” written by state senator Albert Boutwell, was designed to give local school boards the power to decide where students would attend school based on ability, availability of transportation, and academic background. Two more Alabama laws that were passed in 1956 attempted to give local boards the legal means to resist desegregation. One measure allowed school boards to close any school faced with integration and also reasserted local control over education. Another, Amendment 111, also written by Boutwell, was a “freedom of choice law” that allowed parents to decide which schools their children would attend. It also codified separate schools for blacks and whites and provided funding for and allowed teachers to take their public pensions to the numerous whites-only “segregation academies” and private schools that began to arise throughout Alabama and the rest of the South after the Brown decision. In addition, the “Boutwell Amendment” added a clause disavowing the concept that citizens have a “right” to an education at public expense. This clause and the one requiring separate schools would become the core of amendment initiatives in 2004 and 2012. “Freedom of choice” also would become the mantra of integration opponents when numerous desegregation orders were issued in the 1970s. Although the Brown case unlocked the door to desegregation, related federal court rulings, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and many years were required to open that door fully.

Albert Boutwell

Before Brown v. Board, Alabama and other southern states had attempted to equalize school funding and teacher pay for blacks and whites while also passing laws designed to preserve segregation. Between the early 1940s and the early 1950s, pay for black teachers increased by almost 212 percent. Funding for students increased similarly. Even as attempts were made to equalize funding, the state worked harder to preserve segregation. Beginning in 1953, the state allowed local superintendents to place students in schools based on academic preparation. After the Brown decision, the state enacted legislation aimed at circumventing the ruling. A 1955 “pupil placement law,” written by state senator Albert Boutwell, was designed to give local school boards the power to decide where students would attend school based on ability, availability of transportation, and academic background. Two more Alabama laws that were passed in 1956 attempted to give local boards the legal means to resist desegregation. One measure allowed school boards to close any school faced with integration and also reasserted local control over education. Another, Amendment 111, also written by Boutwell, was a “freedom of choice law” that allowed parents to decide which schools their children would attend. It also codified separate schools for blacks and whites and provided funding for and allowed teachers to take their public pensions to the numerous whites-only “segregation academies” and private schools that began to arise throughout Alabama and the rest of the South after the Brown decision. In addition, the “Boutwell Amendment” added a clause disavowing the concept that citizens have a “right” to an education at public expense. This clause and the one requiring separate schools would become the core of amendment initiatives in 2004 and 2012. “Freedom of choice” also would become the mantra of integration opponents when numerous desegregation orders were issued in the 1970s. Although the Brown case unlocked the door to desegregation, related federal court rulings, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and many years were required to open that door fully.

Desegregation Comes Slowly

Gov. Wallace’s Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

Subsequently, the integration of Alabama schools did not begin until 1963, when two key civil rights cases went to trial in the state. That year, attorney Fred Gray filed a local case requiring desegregation in Macon County in Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, which soon became the legal vehicle for desegregating the entire state. The federal Middle District court ordered the admittance of black youths to Tuskegee High School, but even then it took time and customized court orders tailored to individual districts for the slow process of desegregation to begin. A key obstacle was Alabama governor George C. Wallace, who had affirmed his commitment to the cause of segregation in his January 1963 inaugural speech and that summer temporarily blocked two black students from enrolling in the University of Alabama. He also told the education community that he would not support schools that did engage in integration and openly supported segregation academies, including the state’s first, Macon Academy in Tuskegee. Furthermore, while the Macon County Board of Education moved to comply with the court order, Wallace and the State Board of Education made several efforts to circumvent the court’s actions and ultimately closed the school in 1964.

Gov. Wallace’s Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

Subsequently, the integration of Alabama schools did not begin until 1963, when two key civil rights cases went to trial in the state. That year, attorney Fred Gray filed a local case requiring desegregation in Macon County in Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, which soon became the legal vehicle for desegregating the entire state. The federal Middle District court ordered the admittance of black youths to Tuskegee High School, but even then it took time and customized court orders tailored to individual districts for the slow process of desegregation to begin. A key obstacle was Alabama governor George C. Wallace, who had affirmed his commitment to the cause of segregation in his January 1963 inaugural speech and that summer temporarily blocked two black students from enrolling in the University of Alabama. He also told the education community that he would not support schools that did engage in integration and openly supported segregation academies, including the state’s first, Macon Academy in Tuskegee. Furthermore, while the Macon County Board of Education moved to comply with the court order, Wallace and the State Board of Education made several efforts to circumvent the court’s actions and ultimately closed the school in 1964.

Also in 1963, Mobile civil rights activist John L. LeFlore and 27 other African American parents petitioned the Mobile County Board of School Commissioners to develop a desegregation plan for the county’s schools. The board’s refusal to consider such a plan resulted in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the parents filing a suit, Birdie Mae Davis v. Board of School Commissioners, Mobile. Though not as far-ranging as the Lee case, the Mobile suit dealt another blow to segregated schools in Alabama when U.S. Judge Daniel Thomas ordered the integration of the 12th grade in the Mobile County school system, the largest in the state with slightly more than 79,000 students. The problem of integrating schools in Mobile County proved extremely complicated and the effort was only partially successful. The case was eventually dismissed in 1997.

Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr.

It was not until the late 1960s, however, that public schools in the South, Alabama included, were mostly integrated, a consequence largely spurred by two events that also prompted the establishment of more segregation academies. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 provided the federal government with new powers to enforce desegregation, such as withholding federal funds to punish resistant school districts. Then in 1967, U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. also invalidated the freedom of choice and pupil placement act, adjudicated the Lee case, and ordered all non-integrated public schools in Alabama to admit black students, which led to more court cases throughout the state. The reaction of whites to the Civil Rights Act and Johnson’s order typified and set the tone for the rest of the state: White liberals in Tuskegee urged their peers to accept the inevitability of integration, but conservative white parents pulled their children out of schools in large numbers, enrolling them in the segregation academies that were immune to court orders. Most of these schools were established in and around Birmingham, Mobile, and Montgomery and in predominantly black school districts. Some schools still remain, while others have succumbed to demographic changes and financial hardship. As many as 50,000 white students left public schools for these private academies from the mid-1960s into the early 1970s whereas the number of private schools increased from approximately 35 to more than 130 between 1965 and 1975.

Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr.

It was not until the late 1960s, however, that public schools in the South, Alabama included, were mostly integrated, a consequence largely spurred by two events that also prompted the establishment of more segregation academies. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 provided the federal government with new powers to enforce desegregation, such as withholding federal funds to punish resistant school districts. Then in 1967, U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. also invalidated the freedom of choice and pupil placement act, adjudicated the Lee case, and ordered all non-integrated public schools in Alabama to admit black students, which led to more court cases throughout the state. The reaction of whites to the Civil Rights Act and Johnson’s order typified and set the tone for the rest of the state: White liberals in Tuskegee urged their peers to accept the inevitability of integration, but conservative white parents pulled their children out of schools in large numbers, enrolling them in the segregation academies that were immune to court orders. Most of these schools were established in and around Birmingham, Mobile, and Montgomery and in predominantly black school districts. Some schools still remain, while others have succumbed to demographic changes and financial hardship. As many as 50,000 white students left public schools for these private academies from the mid-1960s into the early 1970s whereas the number of private schools increased from approximately 35 to more than 130 between 1965 and 1975.

Alabama largely has come to terms with a new racial order in the post-Brown years but continues to struggle to finance its schools. Mirroring an issue that dates back to policies set in the post-Reconstruction era, Alabamians and their elected representatives consistently provide strong vocal support to high-quality public education but vote down measures designed to raise money for school systems.

Funding Issues

The roots of Alabama’s school funding problem go back to the 1901 Constitution, which hampers the ability of local governments to increase property taxes for support of public schools. Alabama schools are funded by the Education Trust Fund (ETF), which is financed mainly by income tax and sales tax revenues and which makes education spending unpredictable and undependable because those sources of revenue rise or fall as the overall economy rises and falls. As a result, in a process known as “proration” mid-year budget cuts often are required when revenues fall below expectations. This peculiar tax and funding situation also has caused Alabama to fall further behind other southern states in terms of local funding of schools and ratings of educational quality.

The funding disparity between affluent and less affluent districts has resulted in lawsuits and reform movements. More affluent counties have tried to prevent the shifting of state school funds to less affluent counties, and less affluent counties have sued for equity in funding. In 1990, Lawrence County school superintendent DeWayne Key formed the Alabama Coalition for Equity (ACE) and filed suit to force the state to address this inequity. In a related development around that time, a circuit judge found Amendment 111 unconstitutional, but his ruling was not acted upon. In 1993, the court found for the plaintiffs in ACE v. Governor Guy Hunt, ruling that Alabama’s educational funding system was unconstitutional. The result was a sweeping school-funding reform plan called Alabama First, which called for higher taxes, increased school funding, and increased accountability. It was met with opposition by the Alabama Education Association and its leader Paul Hubbert, and it died soon after the reelection of Forrest “Fob” James (1979-1983, 1995-1999) as governor in 1994; James actively opposed the plan.

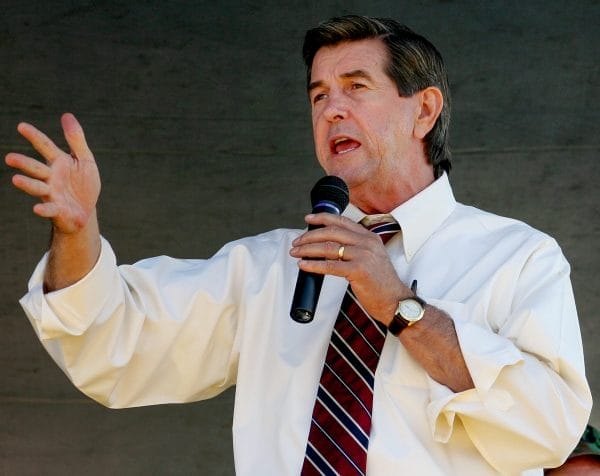

Bob Riley, 2003

Few of the state’s political leaders have made serious attempts to repair the state’s tax structure to improve public education. Gov. Bob Riley (2002-10), however, proposed in the first year of his administration Amendment One, which would have reduced taxes on lower income families, increased taxes on the more affluent, and raised property taxes. The resulting $1.2 billion annual tax windfall would have sent millions of dollars into the ETF and would have allowed the state to fund and support schools more effectively. Riley and many other supporters saw this as a moral and religious issue because it would have eased the tax burden on poorer Alabamians. When put to a statewide vote in 2003, Alabamians defeated it by a vote of 68 percent against, led by the Alabama Farmers Federation and the Christian Coalition of Alabama. The anti-tax viewpoint echoed in the Constitution of 1901 had won yet again, and the state continued to limp its way through the early years of the 21st century. Also trying to improve education funding, a biracial group of individuals from Lawrence and Sumter counties filed suit against the state in Lynch v. Alabama in March 2008. The plaintiffs alleged that limits on property taxes (caps) restrict education funding, were racially motivated, have proven more injurious to rural areas and African Americans than to whites, and that the tax caps violate civil and constitutional rights. Although the court agreed in October 2011 with the testimony of many eminent Alabama historians and legal scholars, on behalf of the plaintiffs, that the Alabama Constitution of 1901 had racist elements, the court could not determine that more recent tax policies were racially motivated. The decision has since been appealed.

Bob Riley, 2003

Few of the state’s political leaders have made serious attempts to repair the state’s tax structure to improve public education. Gov. Bob Riley (2002-10), however, proposed in the first year of his administration Amendment One, which would have reduced taxes on lower income families, increased taxes on the more affluent, and raised property taxes. The resulting $1.2 billion annual tax windfall would have sent millions of dollars into the ETF and would have allowed the state to fund and support schools more effectively. Riley and many other supporters saw this as a moral and religious issue because it would have eased the tax burden on poorer Alabamians. When put to a statewide vote in 2003, Alabamians defeated it by a vote of 68 percent against, led by the Alabama Farmers Federation and the Christian Coalition of Alabama. The anti-tax viewpoint echoed in the Constitution of 1901 had won yet again, and the state continued to limp its way through the early years of the 21st century. Also trying to improve education funding, a biracial group of individuals from Lawrence and Sumter counties filed suit against the state in Lynch v. Alabama in March 2008. The plaintiffs alleged that limits on property taxes (caps) restrict education funding, were racially motivated, have proven more injurious to rural areas and African Americans than to whites, and that the tax caps violate civil and constitutional rights. Although the court agreed in October 2011 with the testimony of many eminent Alabama historians and legal scholars, on behalf of the plaintiffs, that the Alabama Constitution of 1901 had racist elements, the court could not determine that more recent tax policies were racially motivated. The decision has since been appealed.

Into the Twenty-First Century

Efforts also have been undertaken in recent years to remove portions of the 1956 segregationist Boutwell Amendment. In 2004, a proposed statewide amendment to revise Amendment 111 by deleting parts of section 256, which specified separate schools for the races and disavowed a constitutional right to public education and training, and several mentions of the poll tax, was barely defeated. Although segregated schools and the poll tax had been declared illegal years earlier under federal law, the mostly liberal proponents of the measure hoped to remove what was considered racist language whereas the mostly conservative opponents such as Roy Moore were worried that removing the disavowal would imply a right to education and training and lead to higher taxes and more court cases. In 2012, efforts were made to similarly revise the constitution, though retaining the disavowal portion, and the ballot initiative failed overwhelmingly. However, the opposition this time was led in part by the AEA, which feared that approving the new amendment would reaffirm the clause that the state is not obligated to provide education or training. Others noted that its passage would hamper future legal challenges to the state’s funding structure. The Alabama Farmers Federation supported passage, highlighting the removal of racist language and charged that AEA’s opposition was to retain racist language to promote lawsuits and higher taxes. In both cases, national and international observers lamented that Alabama had voted against desegregation, ignoring the complexities of the issue.

Into the twenty-first century, Alabama’s education system, by many measures, compares poorly with other states, hampered by per pupil spending that is among the lowest in the country. The percentage of students at a basic level in 4th and 8th grades is well below the national average, and the high school graduation rate has remained below the national average for at least the last several decades. In recent years, however, the state has made significant strides in improving student achievement in 4th grade reading and mathematics, for instance. In 2022, Alabama was ranked 39th out of 50 states in reading and 40th in math, with a ranking of 47th overall in education.

Further Reading

- Bass, Jack. Taming the Storm: The Life and Times of Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. and the South’s Fight Over Civil Rights. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, 1993.

- Flynt, Wayne. Alabama in the Twentieth Century. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Harvey, Gordon. A Question of Justice: New South Governors and Education, 1968-1976. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

- Harvey, Ira. A History of Educational Finance in Alabama, 1819-1986. Auburn, Ala.: Truman Pierce Institute, 1989.

- Vinik, D. Frank. “The Contrasting Politics of Remedy: The Alabama and Kentucky School Equity Funding Suits.” Journal of Education Finance 22 (Summer 1996): 60-87.