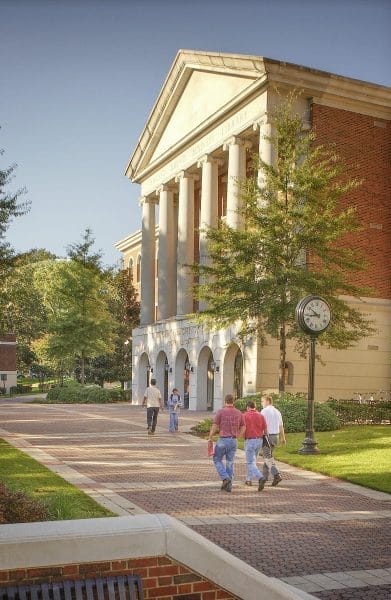

University of Alabama

Clark Hall

Established in 1820, the University of Alabama is one of the two largest public universities in Alabama. It is considered the flagship campus of the University of Alabama System, which includes the University of Alabama (UA) located at Tuscaloosa, the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), and the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH). It offers bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in more than 200 fields of study and consistently is listed among the nation’s top public universities.

Clark Hall

Established in 1820, the University of Alabama is one of the two largest public universities in Alabama. It is considered the flagship campus of the University of Alabama System, which includes the University of Alabama (UA) located at Tuscaloosa, the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), and the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH). It offers bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in more than 200 fields of study and consistently is listed among the nation’s top public universities.

The university is comprised of 13 colleges and schools: College of Arts and Sciences (founded in 1909), Culverhouse College of Commerce and Business Administration (1929), College of Communication and Information Sciences (1997), College of Community Health Sciences (1971), College of Continuing Studies (1983), College of Education (1928), College of Engineering (1909), Graduate School (1924), Honors College (2003), College of Human Environmental Sciences (1987), School of Law (1872), Capstone College of Nursing (1975), and School of Social Work (1965). UA offers the only doctoral programs in the state in anthropology, library and information studies, metallurgical and materials engineering, music, Romance languages, and social work. Its law school is the only publicly supported law school in the state. UA also ranks high nationally among public universities in the number of National Merit Scholars enrolled. It has had more students named to USA Today’s All-USA College Academic Teams than any other school in the nation. On November 1, 2012, UA appointed Judy Bonner as the first woman president in the institution’s history.

Early Years

Gorgas House

In August 1819, the board of trustees met to begin the task of planning the new university, which was created through an act of the Alabama legislature on December 18, 1820. Tuscaloosa was selected as the location for the new university from a field of competitors on December 29, 1827. The state purchased land just outside the city limits for the campus the following spring, and the school opened three years later on April 18, 1831. Situated on 1,000 acres originally a mile from Tuscaloosa, the campus was designed by the state architect, William Nichols. By 1863, six buildings and four residence halls had been constructed.

Gorgas House

In August 1819, the board of trustees met to begin the task of planning the new university, which was created through an act of the Alabama legislature on December 18, 1820. Tuscaloosa was selected as the location for the new university from a field of competitors on December 29, 1827. The state purchased land just outside the city limits for the campus the following spring, and the school opened three years later on April 18, 1831. Situated on 1,000 acres originally a mile from Tuscaloosa, the campus was designed by the state architect, William Nichols. By 1863, six buildings and four residence halls had been constructed.

The university opened in April 1831 with four faculty and 94 students. Freshmen took Latin, Greek, geography, English grammar, history, reading, orthography or composition, and mathematics. Students further along added rhetoric, elocution, French, Spanish or Italian, natural history, botany or some similar subject, natural philosophy accompanied by laboratory demonstrations, logic, moral philosophy, chemistry, geology, mineralogy, intellectual history, evidences of Christianity, and elements of criticism.

The first years of the university did not run smoothly, however. The first president, Alva Woods (1831-37) brought with him a New Englander’s sense of strict duty and discipline that clashed with the students’ southern frontier sense of freedom. As a result, numerous disciplinary problems and conflicts occurred between students and faculty members, including an incident in 1836 in which more than 40 students were suspended for attending a circus. Woods resigned in 1837 and was replaced by Baptist minister Basil Manly, who served until 1855. During his tenure, attempts were made to raise entrance standards as well as to create three different departments or schools: a “normal” department to train secondary teachers, a medical school, and a law school. All failed for lack of interest or support. The school did, however, add and equip the second observatory west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Landon C. Garland (1855-1866) became president in 1855 and called for the creation of a system of military discipline, which was adopted by the board of trustees in July 1860. The students who entered the following fall became cadets, and the student body became the Corps of Cadets, wearing a uniform similar to that of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The changes brought about by military uniforms and drilling, with student officers enforcing the rules, were quickly felt, and student discipline, attendance, and class preparation improved.

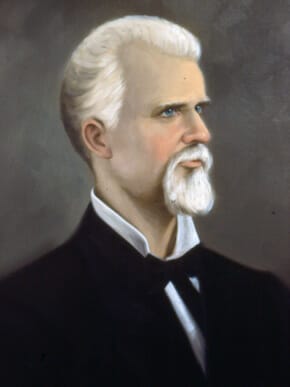

Murfee, James T.

With the coming of the Civil War, members of the Corps of Cadets were sent to camps to drill newly raised units and in some cases, remained with them as officers and non-commissioned officers. Many cadets joined the Confederate Army, but a large number remained behind at the university. They did participate in the war effort, however, serving in the Battle of Chehaw in July 1864 in Macon County, and again, in December 1864, in Mobile to assist in defending the city. They also helped defend the town and campus on the night of April 3, 1865, when U.S. troops under the command of Gen. James H. Wilson entered Tuscaloosa. The students were forced back, and the soldiers burned the campus, leaving only some faculty residences, including the building now known as the Gorgas House, the President’s Mansion, the observatory, and the guard house intact. Despite the destruction, the board of trustees and President Garland were determined to hold classes in the fall of 1866. Although Garland worked hard to procure books and funding, only one student enrolled for the fall semester.

Murfee, James T.

With the coming of the Civil War, members of the Corps of Cadets were sent to camps to drill newly raised units and in some cases, remained with them as officers and non-commissioned officers. Many cadets joined the Confederate Army, but a large number remained behind at the university. They did participate in the war effort, however, serving in the Battle of Chehaw in July 1864 in Macon County, and again, in December 1864, in Mobile to assist in defending the city. They also helped defend the town and campus on the night of April 3, 1865, when U.S. troops under the command of Gen. James H. Wilson entered Tuscaloosa. The students were forced back, and the soldiers burned the campus, leaving only some faculty residences, including the building now known as the Gorgas House, the President’s Mansion, the observatory, and the guard house intact. Despite the destruction, the board of trustees and President Garland were determined to hold classes in the fall of 1866. Although Garland worked hard to procure books and funding, only one student enrolled for the fall semester.

Garland resigned that fall, and the task of rebuilding the campus was given to Col. James Thomas Murfee. He oversaw the plans for the new main building, known as the University Building, which included dormitory space, a library, laboratories, lecture halls, and a hospital. It was completed in 1869, and classes began that fall with 54 students.

Post-War Era

The Round House

Alabama’s 1867 Constitution had completely changed the governance of the university. It eliminated the board of trustees and replaced it with a politicized board of regents that was given the power to appoint the president and faculty, making those positions open to abuse as political rewards. The new board, made up of Unionist Alabamians and recently arrived northerners, undid all the decisions made by the previous board of trustees. Two northerners were nominated for president, but the board of regents elected William Stokes Wyman, who had been on the university faculty since 1855. The regents then named two other faculty members, who would have been acceptable to most supporters of the school, as well as three Ohioans to other faculty positions. Wyman declined his nomination, and did one of the others, and the third seemed similarly inclined. The board then appointed three more Ohioans.

The Round House

Alabama’s 1867 Constitution had completely changed the governance of the university. It eliminated the board of trustees and replaced it with a politicized board of regents that was given the power to appoint the president and faculty, making those positions open to abuse as political rewards. The new board, made up of Unionist Alabamians and recently arrived northerners, undid all the decisions made by the previous board of trustees. Two northerners were nominated for president, but the board of regents elected William Stokes Wyman, who had been on the university faculty since 1855. The regents then named two other faculty members, who would have been acceptable to most supporters of the school, as well as three Ohioans to other faculty positions. Wyman declined his nomination, and did one of the others, and the third seemed similarly inclined. The board then appointed three more Ohioans.

The new president, Reverend Arad S. Lakin, arrived in September, but Wyman, who held the keys, refused to deliver them up, claiming that the board’s actions were illegal. Lakin departed only to return a few weeks later with the head of the board of regents, but both left when targeted by Ryland Randolph in his newspaper, the Independent Monitor. In the following three years, presidents came and went until, in the spring of 1871, the board of regents met with former alumni in a successful effort to save the school. The result was the naming of Nathaniel Lupton (1871-73) as president. After unsuccessful attempts to have the new federally funded agricultural college placed at the university and to receive federal reparations for the burning of the school by federal forces, Lupton was able to establish a law school and impressed the faculty with his ability, courtesy, and loyalty to the institution. In 1876, the board of trustees, appointed by the governor and confirmed by the senate, was reinstated. By the early 1880s, improved finances allowed the trustees to plan a campus expansion that resulted in the construction of five new buildings over the next decade. Under president Henry DeLamar Clayton Sr., who began his three-year tenure in 1886, the university moved away from its traditional classical-education curriculum and added more science and engineering courses and physical education to the curriculum.

Coeducation Comes to UA

Julia Tutwiler

Although colleges and universities across the country had been admitting women for years, coeducation came slowly to the University of Alabama, despite discussions on the subject dating to the 1870s. In June 1892, a member of the university’s board of trustees presented to the board with a petition from Alabama social reformer and teacher Julia Tutwiler to propose the admission of women to UA. Invited to meet with the board, Tutwiler appeared two days later, and before she left the room, a motion was made and seconded to admit women to the three upper classes. The board named a committee charged with reporting on the issue, and at their meeting in June 1893, the board of trustees authorized the enrollment of women at the school.

Julia Tutwiler

Although colleges and universities across the country had been admitting women for years, coeducation came slowly to the University of Alabama, despite discussions on the subject dating to the 1870s. In June 1892, a member of the university’s board of trustees presented to the board with a petition from Alabama social reformer and teacher Julia Tutwiler to propose the admission of women to UA. Invited to meet with the board, Tutwiler appeared two days later, and before she left the room, a motion was made and seconded to admit women to the three upper classes. The board named a committee charged with reporting on the issue, and at their meeting in June 1893, the board of trustees authorized the enrollment of women at the school.

Enrollment was slow at first. In the fall of 1893, only two women enrolled. By 1896, their numbers had increased to just five. Nonetheless, in 1897 the “experiment” was deemed a success, and women were allowed to enter the freshman class. These early coeds took their places in the same classes as the men, taking such courses as chemistry, mineralogy, history, geology, philosophy, English, German, and French.

The military style of discipline had become less and less popular during the latter part of the nineteenth century. With the arrival of James West in the fall of 1900, the situation worsened. West, appointed commandant of cadets and given charge of all military aspects of the university, became exceedingly unpopular with the cadets because of his excessive focus on discipline and allegations of favoritism. A week-long student revolt resulted in the resignation of both the commandant and the university president. The weakened military system remained until 1903, when it was finally abolished.

John William Abercrombie took office in 1902 and served until 1911. He believed that the university could be improved by enhancing the quality of high school education. He raised entrance requirements and established a summer school program for public school teachers. He also reorganized the university’s administrative structure and created the system of schools and colleges that has characterized the university ever since. His “Greater University Campaign” raised money for the construction of three new buildings and an additional residence hall, the first new construction on campus since the late 1880s.

Denny Chimes

In 1912, George H. Denny (1912-1936, 1941) became president, with the goal of building the university into a great institution. Early in his tenure, Denny referred to the University of Alabama as the “capstone” of education in the state, a name by which it has been called ever since. Despite frequent differences with the legislature regarding funding, he was able, through a fundraising campaign in 1922 and careful management, to expand the university. During Denny’s 24 years as president, UA added 14 major buildings, 35 fraternity and sorority houses, and a football stadium. Enrollment increased to almost 5,000, or 11 times the number of students at the university when he arrived, and he also increased the faculty by a factor of almost six. Denny recognized the importance of football in gaining support for the school and expanded the program.

Denny Chimes

In 1912, George H. Denny (1912-1936, 1941) became president, with the goal of building the university into a great institution. Early in his tenure, Denny referred to the University of Alabama as the “capstone” of education in the state, a name by which it has been called ever since. Despite frequent differences with the legislature regarding funding, he was able, through a fundraising campaign in 1922 and careful management, to expand the university. During Denny’s 24 years as president, UA added 14 major buildings, 35 fraternity and sorority houses, and a football stadium. Enrollment increased to almost 5,000, or 11 times the number of students at the university when he arrived, and he also increased the faculty by a factor of almost six. Denny recognized the importance of football in gaining support for the school and expanded the program.

World War II brought major change to UA, as the number of men in regular academic programs declined and the number of women increased. The 1945 yearbook, the Corolla, noted that most of the men in the class of 1945 went into the armed services. In addition, U.S. Army and Navy training programs brought large numbers of military personnel to campus in 1943 and 1944. In the postwar years, the university faced the challenge of housing and teaching the influx of returning soldiers who, thanks to the GI Bill, sought a college education. The school added more than 160 instructors and met increased housing needs by acquiring from the federal government temporary housing for more than 600 families and turning Northington General Hospital, which had served as a major burn hospital during the war, into additional housing for veterans. In the post-war years, the university added eight doctoral programs as well as the School of Nursing and the School of Dentistry, located in Birmingham. Faculty members were given a role in university governance, and the administration undertook a long-range study of needs.

UA and Civil Rights

Autherine Lucy, Thurgood Marshall, and Arthur Shores

In 1956, after a three-year court case, UA admitted Autherine Lucy as its first African American student. Lucy attended classes without incident for two days, although there were protests in town and on campus on those nights. On Monday, February 6, a crowd of approximately 500 people gathered on campus to protest her admission. As she was driven from one building to another, onlookers threw rocks, and the crowd increased in size. Later in the morning, the university’s board of trustees suspended her ostensibly for her own safety. Some 30 years later, Lucy earned a graduate degree from UA, and the university named an endowed scholarship in her honor.

Autherine Lucy, Thurgood Marshall, and Arthur Shores

In 1956, after a three-year court case, UA admitted Autherine Lucy as its first African American student. Lucy attended classes without incident for two days, although there were protests in town and on campus on those nights. On Monday, February 6, a crowd of approximately 500 people gathered on campus to protest her admission. As she was driven from one building to another, onlookers threw rocks, and the crowd increased in size. Later in the morning, the university’s board of trustees suspended her ostensibly for her own safety. Some 30 years later, Lucy earned a graduate degree from UA, and the university named an endowed scholarship in her honor.

Gov. Wallace’s Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

In 1963, Vivian Malone and James Hood again attempted to integrate the university, filing suit and gaining admittance to UA, but Gov. George C. Wallace vowed to prevent the integration of the school by blocking the doorway, if necessary. On June 11, standing in front of Foster Auditorium in a largely staged event, Wallace was asked by Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to stand aside. After Wallace read a prepared statement reiterating that he would not allow the students to pass, Katzenback informed him that the students would register and go to school and then withdrew. Later that afternoon, after Pres. John F. Kennedy had nationalized the Alabama National Guard, Brig. Gen. Henry Graham of the Thirty-first (Dixie) Division of the National Guard, accompanied by the two students, ordered Wallace to “step aside on orders from the President of the United States.” After thanking the people of Alabama for their restraint, Wallace stepped aside. Vivian Malone and James Hood then registered.

Gov. Wallace’s Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

In 1963, Vivian Malone and James Hood again attempted to integrate the university, filing suit and gaining admittance to UA, but Gov. George C. Wallace vowed to prevent the integration of the school by blocking the doorway, if necessary. On June 11, standing in front of Foster Auditorium in a largely staged event, Wallace was asked by Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to stand aside. After Wallace read a prepared statement reiterating that he would not allow the students to pass, Katzenback informed him that the students would register and go to school and then withdrew. Later that afternoon, after Pres. John F. Kennedy had nationalized the Alabama National Guard, Brig. Gen. Henry Graham of the Thirty-first (Dixie) Division of the National Guard, accompanied by the two students, ordered Wallace to “step aside on orders from the President of the United States.” After thanking the people of Alabama for their restraint, Wallace stepped aside. Vivian Malone and James Hood then registered.

New Schools Added

The 1960s were a time of growth and organizational change as well. In 1966, the board of trustees merged the growing University of Alabama School of Medicine, which had moved to Birmingham in 1945, with the Birmingham Extension Center to become the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Three years later, the Huntsville Extension Center became the University of Alabama in Huntsville, and in the same year, the University of Alabama System was established by the trustees.

University of Alabama Bruno Business Library

In subsequent years, enrollment increased, entrance requirements and academic standards were raised, faculty expanded, and more research funds became available. In the 1990s, the university emphasized quality research programs and economic development. Among the programs established were the Blount Undergraduate Initiative, a special, four-year liberal arts program, and the International Honors Program. In 1995, UA established the Blackburn Institute in honor of former dean of students John L. Blackburn. The institute provides students with opportunities to participate in outreach and civic engagement and improve the lives of Alabamians across the state.

University of Alabama Bruno Business Library

In subsequent years, enrollment increased, entrance requirements and academic standards were raised, faculty expanded, and more research funds became available. In the 1990s, the university emphasized quality research programs and economic development. Among the programs established were the Blount Undergraduate Initiative, a special, four-year liberal arts program, and the International Honors Program. In 1995, UA established the Blackburn Institute in honor of former dean of students John L. Blackburn. The institute provides students with opportunities to participate in outreach and civic engagement and improve the lives of Alabamians across the state.

In 2003, Robert Witt was chosen president in 2003 and announced a 10-year goal of increasing enrollment from just over 20,000 to 28,000. By 2015, the school had approximately 37,600 students enrolled. Efforts to raise salaries for faculty and staff and to increase financial aid for students were also successful. In addition, a major building program resulted in 20 new facilities opening during the same period. In November 2010, UA dedicated a plaza and clock tower outside the Foster Auditorium to honor the students who desegregated the university. Judy L. Bonner, who earned a doctorate in nutrition, served as UA’s first woman president from 2012 to 2015, and Stuart R. Bell, a mechanical engineering professor, became president in 2015.

The University of Alabama Museums operates a number of historic sites and museums on the campus and in the area. These include the Mildred Westervelt Warner Transportation Museum, the Alabama Museum of Natural History, Moundville Archaeological Park, the Gorgas House Museum, and the Paul R. Jones Museum. Additionally, the campus also hosts the Paul W. Bryant Museum, which honors the legendary football coach.

Athletics have been an important part of UA life since its earliest years. The first team sport played at UA was apparently baseball, played by an unofficial team against teams organized by federal troops during Reconstruction in the 1870s. From that beginning, UA has fielded men’s varsity teams in baseball, basketball, cross country, football, golf, swimming and diving, tennis, and track and field, and women’s teams in basketball, cross country, golf, gymnastics, rowing, soccer, softball, swimming and diving, tennis, track and field, and volleyball. The University of Alabama has won 16 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) championships and many conference titles.

Bryant-Denny Stadium

The name Crimson Tide is said to have been originated by a sports writer describing the 1907 Alabama-Auburn football game held on an exceedingly muddy field in Birmingham. He described the team as “a crimson tide in a sea of mud.” The name caught on. When a U.S. military band played a concert in Tuscaloosa in 1919, Gen. John J. Pershing was quoted as having said that regimental bands were “worth more than a million dollars to the American Expeditionary Forces.” It was widely agreed that the university’s band was worth as much to the University of Alabama, and the Million Dollar Band was born. The affiliation of an elephant with university athletics is said to date to late 1930, when Rosenberger’s Birmingham Trunk Company, whose trademark was a red elephant standing on a trunk, presented the members of the Rose Bowl-bound football team with red elephant good luck charms. A live elephant was a feature of homecoming parades in the 1940s, but by 1950 the practice ceased because of the cost. Big Al, the costumed elephant mascot, first appeared at the 1979 Sugar Bowl.

Bryant-Denny Stadium

The name Crimson Tide is said to have been originated by a sports writer describing the 1907 Alabama-Auburn football game held on an exceedingly muddy field in Birmingham. He described the team as “a crimson tide in a sea of mud.” The name caught on. When a U.S. military band played a concert in Tuscaloosa in 1919, Gen. John J. Pershing was quoted as having said that regimental bands were “worth more than a million dollars to the American Expeditionary Forces.” It was widely agreed that the university’s band was worth as much to the University of Alabama, and the Million Dollar Band was born. The affiliation of an elephant with university athletics is said to date to late 1930, when Rosenberger’s Birmingham Trunk Company, whose trademark was a red elephant standing on a trunk, presented the members of the Rose Bowl-bound football team with red elephant good luck charms. A live elephant was a feature of homecoming parades in the 1940s, but by 1950 the practice ceased because of the cost. Big Al, the costumed elephant mascot, first appeared at the 1979 Sugar Bowl.

Further Reading

- Center, Clark E., Jr. “The Burning of the University of Alabama.” Alabama Heritage 16 (April 1990): 30-45.

- Clark, E. Culpepper. The Schoolhouse Door: Segregation’s Last Stand at the University of Alabama. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Sellers, James B. History of the University of Alabama. Volume I: 1818-1902. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1953.

- Wolfe, Suzanne Rau. The University of Alabama: A Pictorial History. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1983.