Birmingham District Coal Strike of 1908

Birmingham Coal Miners

In 1908, Birmingham witnessed one of the most remarkable labor disputes in American history. A bitter and often violent two-month strike pitted one of the South’s few viable interracial labor unions, District 20 of the United Mine Workers, against northern Alabama‘s “Big Mules.” the Birmingham district’s politically influential, wealthy industrial employers. The miners’ crushing defeat in the strike set the tone for labor relations in the coalfields, and in industrial Birmingham more generally. The widespread perception that the state had forcefully intervened on the side of coal employers alienated many. But perhaps most importantly, the union’s disarray in the wake of its defeat also greatly weakened one of the few organizations in Jim Crow Alabama that had managed, however tenuously, to bring black and white workers together.

Birmingham Coal Miners

In 1908, Birmingham witnessed one of the most remarkable labor disputes in American history. A bitter and often violent two-month strike pitted one of the South’s few viable interracial labor unions, District 20 of the United Mine Workers, against northern Alabama‘s “Big Mules.” the Birmingham district’s politically influential, wealthy industrial employers. The miners’ crushing defeat in the strike set the tone for labor relations in the coalfields, and in industrial Birmingham more generally. The widespread perception that the state had forcefully intervened on the side of coal employers alienated many. But perhaps most importantly, the union’s disarray in the wake of its defeat also greatly weakened one of the few organizations in Jim Crow Alabama that had managed, however tenuously, to bring black and white workers together.

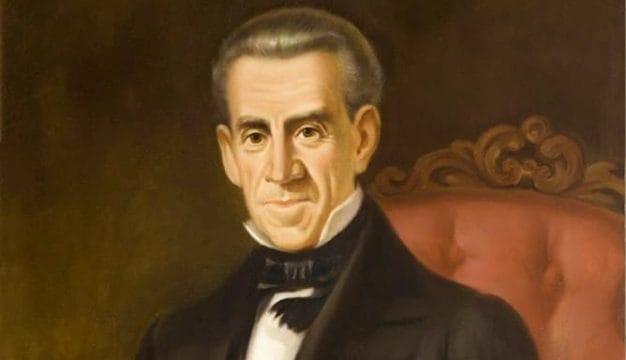

The seeds of confrontation between coal miners and mine owners had been brewing for some time. Small-scale mining had been underway since before the Civil War, but the discovery of substantial coal and iron deposits and the founding of Birmingham in 1871 accelerated production. By the late nineteenth century, city boosters were confidently predicting that the district would overtake Pittsburgh as the nation’s leading steel producer, but coal operators calculated that low labor costs would be critical in gaining a competitive edge over their more established northern rivals. The availability of a large population of destitute freedmen and impoverished whites in the vicinity of the coalfields offered mine owners an important advantage: workers who were both desperate enough to settle for meager wages and so thoroughly divided along racial lines that they would not organize to protest their predicament.

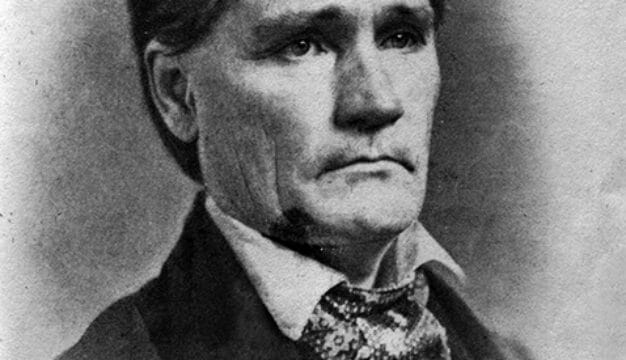

Guard at a Coal Mining Company Town

District 20 of the United Mine Workers had been formed out of the remnants of a statewide miners’ union in 1898, but its ability to deliver decent wages and working conditions to its members was sharply limited by the power of the mine employers. At the turn of the century, when African Americans made up more than half of the mining workforce, the union claimed 10,000 members. By 1903, however, it had been pushed onto the defensive when the district’s largest employer, Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI), refused to renew the union’s contract. A year later TCI led the three largest mine employers in severing relations with the UMW and declaring they would hire only non-union workers. The operator’s resolve to root out the UMW was further strengthened in 1907, when the then-largest corporation in the world—U.S. Steel—bought out TCI. In July 1908, most of the small remaining mine operators followed TCI’s lead and demanded sharp wage reductions. This move was recognized by both the UMW and its adversaries as an attempt to extinguish the union’s presence in the Birmingham district. The stage was thus set for the clashes that followed.

Guard at a Coal Mining Company Town

District 20 of the United Mine Workers had been formed out of the remnants of a statewide miners’ union in 1898, but its ability to deliver decent wages and working conditions to its members was sharply limited by the power of the mine employers. At the turn of the century, when African Americans made up more than half of the mining workforce, the union claimed 10,000 members. By 1903, however, it had been pushed onto the defensive when the district’s largest employer, Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI), refused to renew the union’s contract. A year later TCI led the three largest mine employers in severing relations with the UMW and declaring they would hire only non-union workers. The operator’s resolve to root out the UMW was further strengthened in 1907, when the then-largest corporation in the world—U.S. Steel—bought out TCI. In July 1908, most of the small remaining mine operators followed TCI’s lead and demanded sharp wage reductions. This move was recognized by both the UMW and its adversaries as an attempt to extinguish the union’s presence in the Birmingham district. The stage was thus set for the clashes that followed.

District 20 declared a strike to commence on July 8, 1908, and the early momentum seemed to be with the union. Although only 4,000 of 20,000 miners walked out on the first day, by the end of the first week some 30 new union locals had been formed, and more than half the mine workforce had joined the walkout by the end of the second week. Among the miners newly organized into the union were a number of men who had been strikebreakers only several years earlier. In addition, the national press reported on the UMW’s effectiveness in shutting down mine operations through mass picketing. Numerous armed confrontations erupted between strikers and company guards: miners were convinced that the only effective way to win their strike was to shut down coal production; coal operators were determined to continue, even if it meant employing strikebreakers in place of their regular workforce. In these clashes, the union men seemed to be able to give as good as they got.

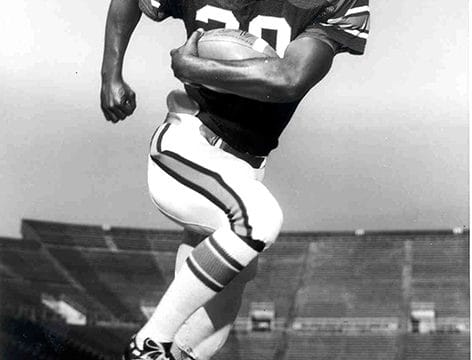

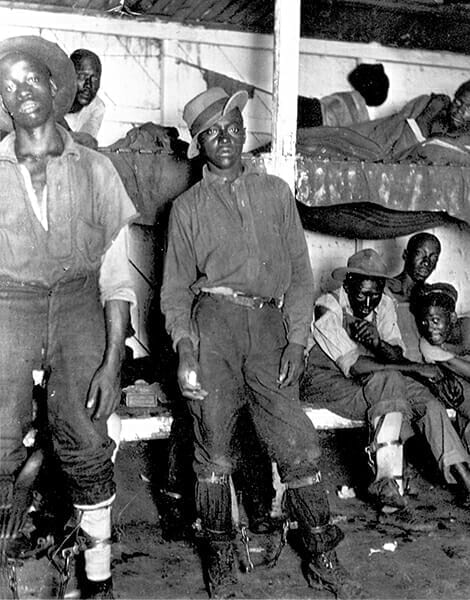

Incarcerated Mine Workers, 1907

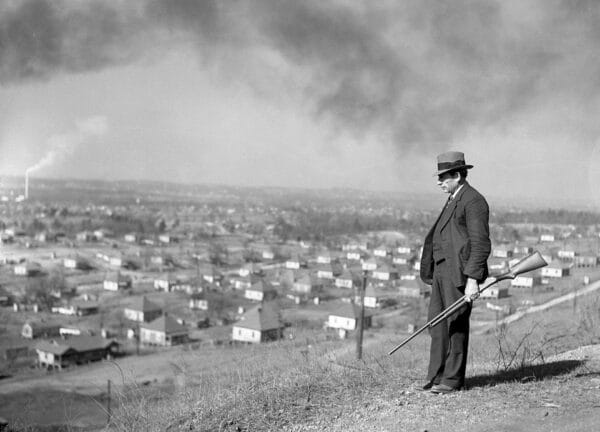

By the end of July a sense of panic gripped district operators. The strike was more effective than they had anticipated, and the union seemed poised to win converts among workers in the largest mining operations. Mine owners resorted to a number of aggressive measures in their efforts to counter these developments, such as dispatching labor recruiters as far away as New York’s Ellis Island to hire immigrant strikebreakers and increasing their use of unpaid convicts leased from the state to maintain coal production. Mine owners also deputized hundreds of armed men to confront the workers and urged Gov. Braxton Bragg Comer to declare martial law and dispatch state troops into the coalfields, a request he eventually granted. In addition, owners and their supporters in Birmingham’s business community openly advocated vigilantism and resorted increasingly to inflammatory rhetoric to rouse white Alabamians against the interracial UMW. The racial undercurrent of the public condemnation of the UMW became increasingly apparent after early August.

Incarcerated Mine Workers, 1907

By the end of July a sense of panic gripped district operators. The strike was more effective than they had anticipated, and the union seemed poised to win converts among workers in the largest mining operations. Mine owners resorted to a number of aggressive measures in their efforts to counter these developments, such as dispatching labor recruiters as far away as New York’s Ellis Island to hire immigrant strikebreakers and increasing their use of unpaid convicts leased from the state to maintain coal production. Mine owners also deputized hundreds of armed men to confront the workers and urged Gov. Braxton Bragg Comer to declare martial law and dispatch state troops into the coalfields, a request he eventually granted. In addition, owners and their supporters in Birmingham’s business community openly advocated vigilantism and resorted increasingly to inflammatory rhetoric to rouse white Alabamians against the interracial UMW. The racial undercurrent of the public condemnation of the UMW became increasingly apparent after early August.

Alabama National Guardsmen, 1908

The most remarkable feature of the strike was the union’s ability to unite miners across the racial divide, a development that was unique not only for Birmingham, but for American society as a whole during this oppressive period in race relations. A parade of striking black and white miners through the streets of Jasper provoked fury among members of Birmingham’s business community, who warned the UMW that its policy of biracial organizing would ignite racial violence. Prominent mine owners denounced the UMW’s interracial workforce as an insult to southern tradition and called for armed state intervention against the racially mixed strikers. In mid-August, black UMW member William Millin was snatched from the jail at Brighton and lynched by two mine deputies, an outrage that provoked fierce, armed retaliation against company guards by a racially mixed group of union miners. The atmosphere seemed to portend more of such violence.

Alabama National Guardsmen, 1908

The most remarkable feature of the strike was the union’s ability to unite miners across the racial divide, a development that was unique not only for Birmingham, but for American society as a whole during this oppressive period in race relations. A parade of striking black and white miners through the streets of Jasper provoked fury among members of Birmingham’s business community, who warned the UMW that its policy of biracial organizing would ignite racial violence. Prominent mine owners denounced the UMW’s interracial workforce as an insult to southern tradition and called for armed state intervention against the racially mixed strikers. In mid-August, black UMW member William Millin was snatched from the jail at Brighton and lynched by two mine deputies, an outrage that provoked fierce, armed retaliation against company guards by a racially mixed group of union miners. The atmosphere seemed to portend more of such violence.

The mine operators’ increasingly strident appeals for forceful intervention, supported by lurid reports of “racial mixing” among striking miners in Birmingham’s business press, eventually won over Governor Comer. In late August, he summoned UMW leaders to his office and warned that legislators would not tolerate what they perceived as efforts to promote equality among black and white miners. Union leaders denied such intentions, but their efforts were in vain. Under the guise of containing a public health nuisance, Comer ordered the Alabama National Guard on August 26 to cut down the tent colonies that had become home to those strikers evicted from company housing. Four days later, union officials declared the strike over, and despite grass-roots efforts to continue the strike, the scale of the defeat was soon apparent. Mine owners, however, relished the new situation, confident that they could revitalize the coal industry on the basis of a more compliant workforce. One year later, the mines had returned to normal operations, and the miners’ efforts toward labor reforms had ended in utter failure.

Additional Resources

Brown, Edwin L. and Colin J. David, eds. It is Union and Liberty: Alabama Coal Miners and the UMW. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

Curtin, Mary Ellen. Black Prisoners and their World: Alabama, 1865-1900. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2000.

Kelly, Brian. Race, Class and Power in the Alabama Coalfields, 1908-1921. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Letwin, Daniel L. The Challenge of Interracial Unionism: Alabama Coal Miners, 1878-1921. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Lewis, Ronald L. Black Coal Miners in America: Race, Class and Community Conflict, 1780-1980. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1987.

Ward, Robert David, and William Warren Rogers. Convicts, Coal and the Banner Mine Tragedy. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1987.