Birmingham

Birmingham

Located in the north-central part of Alabama, Birmingham is the state’s most populous city and the seat of Jefferson County. The youngest of the state’s major cities, Birmingham was founded in 1871 at the crossing of two rail lines near one of the world’s richest deposits of minerals. The city was named for Birmingham, England, the center of that country’s iron industry. The new Alabama city boomed so quickly that it came to be known as the “Magic City.” It later became known as the “Pittsburgh of the South” after the Pennsylvania center of iron and steel production. Birmingham has survived booms and busts, labor unrest, and civil rights tragedies and triumphs; today it is home to one of the nation’s largest banking centers as well as world-class medical facilities. Birmingham has a mayor-council form of government, with its mayor and nine council members being elected every four years.

Birmingham

Located in the north-central part of Alabama, Birmingham is the state’s most populous city and the seat of Jefferson County. The youngest of the state’s major cities, Birmingham was founded in 1871 at the crossing of two rail lines near one of the world’s richest deposits of minerals. The city was named for Birmingham, England, the center of that country’s iron industry. The new Alabama city boomed so quickly that it came to be known as the “Magic City.” It later became known as the “Pittsburgh of the South” after the Pennsylvania center of iron and steel production. Birmingham has survived booms and busts, labor unrest, and civil rights tragedies and triumphs; today it is home to one of the nation’s largest banking centers as well as world-class medical facilities. Birmingham has a mayor-council form of government, with its mayor and nine council members being elected every four years.

Early History

Birmingham is located in Jones Valley, one of the southernmost valleys of the Appalachian mountain chain. Veterans of Gen. Andrew Jackson’s army that defeated the Creeks at Horseshoe Bend were the first settlers to reach the area in 1815. With inadequate transportation to connect early settlements such as Jonesboro and Elyton to the rest of the state and little fertile soil to benefit the state’s cotton economy, the area grew slowly in the first half of the nineteenth century. After the Civil War, however, the development of railroads within Jones Valley along with the presence of rich minerals nearby paved the way for the founding of a new city.

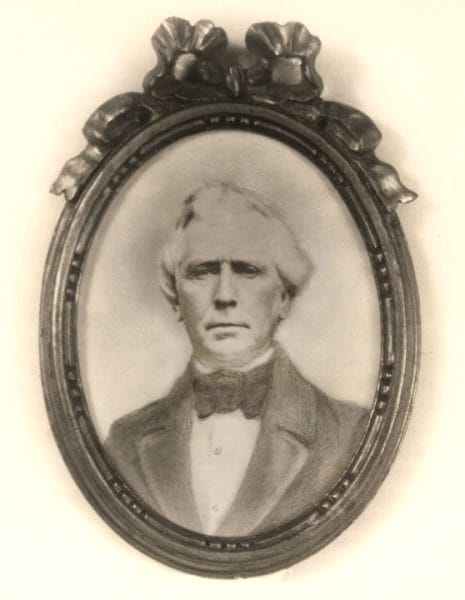

James Powell

Recognizing the area’s potential, a group of investors and promoters of the North and South Railroad (which later became the Louisville and Nashville Railroad) met with banker Josiah Morris in Montgomery on December 18, 1870, and organized the Elyton Land Company for the purpose of building a new city in Jefferson County. The company met again in January 1871, and chose as its president James R. Powell, who had recently returned from Birmingham, England’s iron and steel center, and suggested that the new Alabama industrial center be given the same name. A flamboyant and colorful promoter for the proposed city, Powell became known as the “Duke of Birmingham.” He advertised across the state and nation announcing lots for sale in the new city on June 1, 1871, and six months after the lots sold, the city was chartered by the state legislature on December 19, 1871. Gov. Robert Lindsay appointed Robert Henley to a two-year term as Birmingham’s first mayor. In 1873, Powell was elected mayor and quickly had the legislature call for a vote to allow Jefferson County residents to choose between Elyton and Birmingham as the county seat. In a bitter contest, Powell courted newly enfranchised black residents, who voted overwhelmingly for Birmingham.

James Powell

Recognizing the area’s potential, a group of investors and promoters of the North and South Railroad (which later became the Louisville and Nashville Railroad) met with banker Josiah Morris in Montgomery on December 18, 1870, and organized the Elyton Land Company for the purpose of building a new city in Jefferson County. The company met again in January 1871, and chose as its president James R. Powell, who had recently returned from Birmingham, England’s iron and steel center, and suggested that the new Alabama industrial center be given the same name. A flamboyant and colorful promoter for the proposed city, Powell became known as the “Duke of Birmingham.” He advertised across the state and nation announcing lots for sale in the new city on June 1, 1871, and six months after the lots sold, the city was chartered by the state legislature on December 19, 1871. Gov. Robert Lindsay appointed Robert Henley to a two-year term as Birmingham’s first mayor. In 1873, Powell was elected mayor and quickly had the legislature call for a vote to allow Jefferson County residents to choose between Elyton and Birmingham as the county seat. In a bitter contest, Powell courted newly enfranchised black residents, who voted overwhelmingly for Birmingham.

Soon after Birmingham became the county seat, its very existence was threatened by two events. In July, a cholera epidemic hit many southern cities, and Birmingham suffered greatly because it had little clean water and few adequate sewage facilities. Thousands fled the city. Just as cooler fall weather began to bring an end to the epidemic, the economic Panic of 1873 chilled Birmingham’s real estate boom. As no significant industries had yet been established to create a sufficient number of jobs, people were again forced to leave. Birmingham however, survived these early misfortunes as a result of its nearby rich mineral deposits, which soon made it the industrial center of the New South.

Economic Development

Sloss Company Brookside Coke Ovens

In 1878, Truman H. Aldrich, James W. Sloss, and Henry F. DeBardeleben, owners of the Pratt Coal and Coke Company, provided a major stimulus for Birmingham’s recovery from the 1873 recession and for its future economic growth by opening the nearby Pratt mines. Henry Debardeleben then joined with Thomas T. Hillman to construct the Alice Furnaces, facilitating the large-scale production of pig iron. In June 1881, Sloss began constructing the area’s second set of blast furnaces, known then as the City Furnaces, in eastern Birmingham. The Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TCI) opened facilities in Birmingham soon after and purchased many of the properties held by DeBardeleben and Aldrich. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad aided these flourishing enterprises by investing money and providing special freight rates. As a result of these events, Birmingham’s production of pig iron increased more than tenfold between 1880 and 1890.

Sloss Company Brookside Coke Ovens

In 1878, Truman H. Aldrich, James W. Sloss, and Henry F. DeBardeleben, owners of the Pratt Coal and Coke Company, provided a major stimulus for Birmingham’s recovery from the 1873 recession and for its future economic growth by opening the nearby Pratt mines. Henry Debardeleben then joined with Thomas T. Hillman to construct the Alice Furnaces, facilitating the large-scale production of pig iron. In June 1881, Sloss began constructing the area’s second set of blast furnaces, known then as the City Furnaces, in eastern Birmingham. The Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TCI) opened facilities in Birmingham soon after and purchased many of the properties held by DeBardeleben and Aldrich. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad aided these flourishing enterprises by investing money and providing special freight rates. As a result of these events, Birmingham’s production of pig iron increased more than tenfold between 1880 and 1890.

Birmingham had become the region’s leading industrial city, evolving from a rough and tumble “boom town” of muddy streets, saloons, fistfights, and shootouts to a civilized city with paved streets, gaslights, telephone service, and a public school system. Continued industrial expansion in the 1890s also spurred the rapid growth of unions, particularly among railroad workers, miners, and the building trades.

Birmingham Coal Miners, 1937

The two most important economic developments in Birmingham between 1900 and the Great Depression were the purchase of TCI by U.S. Steel in 1907, which brought financial resources to the city, and the completion of the lock-and-dam system on the Tombigbee and Warrior Rivers in 1915, which provided Birmingham manufacturers with cheap water transportation for their goods all the way to Mobile. Birmingham quickly became the transportation hub of the mid-South. Just as the city’s economy was beginning to take off again, the stock market crashed in October 1929, throwing thousands of residents out of work and prompting the Hoover administration to call Birmingham “the hardest hit city in the nation.” U.S. Steel shut down its Birmingham mills and the city remained depressed for eight years. Birmingham recovered from the Depression with the outbreak of World War II as the city’s steel mills became an important part of the nation’s arsenal. After the war, Birmingham diversified its economy with 140 new industries that manufactured farm equipment, chemicals, byproducts used for road building, nails, wire, cement, cottonseed oil, and many other goods. With these new industries, along with Hayes International Aircraft and the launch of a modern medical complex, Birmingham in the 1950s had the potential to soar into the 1960s. Instead, city officials and residents were faced with a civil rights struggle of epic proportions that left the city’s national reputation in shambles and greatly hampered its ability to attract investors.

Birmingham Coal Miners, 1937

The two most important economic developments in Birmingham between 1900 and the Great Depression were the purchase of TCI by U.S. Steel in 1907, which brought financial resources to the city, and the completion of the lock-and-dam system on the Tombigbee and Warrior Rivers in 1915, which provided Birmingham manufacturers with cheap water transportation for their goods all the way to Mobile. Birmingham quickly became the transportation hub of the mid-South. Just as the city’s economy was beginning to take off again, the stock market crashed in October 1929, throwing thousands of residents out of work and prompting the Hoover administration to call Birmingham “the hardest hit city in the nation.” U.S. Steel shut down its Birmingham mills and the city remained depressed for eight years. Birmingham recovered from the Depression with the outbreak of World War II as the city’s steel mills became an important part of the nation’s arsenal. After the war, Birmingham diversified its economy with 140 new industries that manufactured farm equipment, chemicals, byproducts used for road building, nails, wire, cement, cottonseed oil, and many other goods. With these new industries, along with Hayes International Aircraft and the launch of a modern medical complex, Birmingham in the 1950s had the potential to soar into the 1960s. Instead, city officials and residents were faced with a civil rights struggle of epic proportions that left the city’s national reputation in shambles and greatly hampered its ability to attract investors.

Civil Rights Movement

Sixteenth Street Church Bombing

African Americans began moving into Birmingham to escape the white-owned farms where they had once toiled as slaves and later as sharecroppers. By 1880 African Americans comprised more than half of Birmingham’s industrial workers. Working and living conditions were bad enough, but black citizens’ lives were made more miserable by Birmingham’s deeply entrenched system of segregation. Nicknamed “Bombingham” for the many racially motivated bombings of black homes, the city became a focal point for the national civil rights struggle after the brutal treatment of the Freedom Riders in 1961. Later, Fred Shuttlesworth and other leaders of the Birmingham movement invited Martin Luther King Jr. to participate in a protest of segregated downtown businesses in 1963 that came to be known as the “Birmingham Campaign.” King was arrested during these demonstrations and wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” as a response to an opinion piece by white ministers to end the protests.

Sixteenth Street Church Bombing

African Americans began moving into Birmingham to escape the white-owned farms where they had once toiled as slaves and later as sharecroppers. By 1880 African Americans comprised more than half of Birmingham’s industrial workers. Working and living conditions were bad enough, but black citizens’ lives were made more miserable by Birmingham’s deeply entrenched system of segregation. Nicknamed “Bombingham” for the many racially motivated bombings of black homes, the city became a focal point for the national civil rights struggle after the brutal treatment of the Freedom Riders in 1961. Later, Fred Shuttlesworth and other leaders of the Birmingham movement invited Martin Luther King Jr. to participate in a protest of segregated downtown businesses in 1963 that came to be known as the “Birmingham Campaign.” King was arrested during these demonstrations and wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” as a response to an opinion piece by white ministers to end the protests.

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

The city was then publicly shamed in the media by Police Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor‘s use of fire hoses and police dogs to drive back thousands of youthful demonstrators in early May 1963. Following several weeks of demonstrations, civil rights and business leaders reached an agreement that ended some of the segregationist barriers. This spirit of good will was soon shattered by the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, which claimed the lives of four young girls. That horrific event, more than anything else, prompted the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed racial segregation in public accommodations in America. Also, with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, African Americans were increasingly able to participate in the city’s civic and governmental affairs, culminating in the 1979 election of Richard Arrington Jr. as the city’s first black mayor.

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

The city was then publicly shamed in the media by Police Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor‘s use of fire hoses and police dogs to drive back thousands of youthful demonstrators in early May 1963. Following several weeks of demonstrations, civil rights and business leaders reached an agreement that ended some of the segregationist barriers. This spirit of good will was soon shattered by the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, which claimed the lives of four young girls. That horrific event, more than anything else, prompted the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed racial segregation in public accommodations in America. Also, with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, African Americans were increasingly able to participate in the city’s civic and governmental affairs, culminating in the 1979 election of Richard Arrington Jr. as the city’s first black mayor.

Modern Birmingham

UAB’s Heritage Hall

Birmingham today is a modern city of the New South boasting one of the finest medical and research centers in the country at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). In addition to the continued presence of several of the nation’s largest steelmakers, including U.S. Steel, McWane, and Nucor, Birmingham is now a center of bioscience and technology development and the home to some of the nation’s top construction and engineering firms. The Birmingham metropolitan area is Alabama’s largest commercial center and has become one of the nation’s largest banking centers. Beginning in the mid-1970s, commercial construction in the downtown area gave the city an impressive modern skyline.

UAB’s Heritage Hall

Birmingham today is a modern city of the New South boasting one of the finest medical and research centers in the country at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). In addition to the continued presence of several of the nation’s largest steelmakers, including U.S. Steel, McWane, and Nucor, Birmingham is now a center of bioscience and technology development and the home to some of the nation’s top construction and engineering firms. The Birmingham metropolitan area is Alabama’s largest commercial center and has become one of the nation’s largest banking centers. Beginning in the mid-1970s, commercial construction in the downtown area gave the city an impressive modern skyline.

Between 2006 and 2009, Larry Langford, who was then mayor of Birmingham, and six former members of the Jefferson County Commission were convicted of a variety of corruption charges, including bribery, conspiracy, mail fraud, and money-laundering. On January 17, 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal of Langford’s conviction.

Demographics

According to 2020 Census estimates, Birmingham recorded a population of 210,928,. The greater metropolitan area—which includes numerous surrounding suburb cities such as Hoover, Vestavia Hills, Bessemer, Alabaster, Homewood, Mountain Brook, Hueytown, Center Point, Pelham, Trussville, Gardendale, Fairfield, Forestdale, Leeds, Pleasant Grove, Irondale, Tarrant, and Fultondale—had a population of approximately 1,350,646. Of that total, 68.3 percent of respondents identified themselves as African American, 26.6 percent white, 4.1 percent Hispanic, 2.0 percent as two or more races, 1.2 percent Asian, and 0.2 percent American Indian. The city’s median household income was $38,832, and the per capita income was $25,725.

Employment

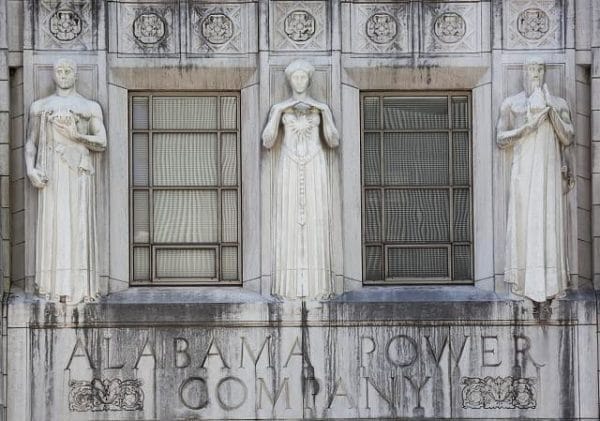

Alabama Power Building Detail

UAB, which boasts one of the finest medical and research centers in the nation, is by far the city’s largest employer, with 18,750 employees. Other leading employers include AT&T, Regions Bank, Birmingham Board of Education, City of Birmingham, Jefferson County Board of Education, Children’s Health System, Wells Fargo (formerly Wachovia), Alabama Power Company, and Blue Cross-Blue Shield of Alabama.

Alabama Power Building Detail

UAB, which boasts one of the finest medical and research centers in the nation, is by far the city’s largest employer, with 18,750 employees. Other leading employers include AT&T, Regions Bank, Birmingham Board of Education, City of Birmingham, Jefferson County Board of Education, Children’s Health System, Wells Fargo (formerly Wachovia), Alabama Power Company, and Blue Cross-Blue Shield of Alabama.

According to 2020 Census estimates, the workforce in Birmingham was divided among the following industrial categories:

- Educational services, and health care and social assistance (27.1 percent)

- Retail trade (12.6 percent)

- Arts, entertainment, recreation, and accommodation and food services (10.6 percent)

- Professional, scientific, management, and administrative and waste management services (10.0 percent)

- Manufacturing (8.3 percent)

- Finance, insurance, and real estate, rental, and leasing (6.9 percent)

- Transportation and warehousing and utilities (5.6 percent)

- Other services, except public administration (5.0 percent)

- Construction (4.9 percent)

- Public administration (3.8 percent)

- Information (2.5 percent)

- Wholesale trade (2.4 percent)

- Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, and extractive (0.2 percent)

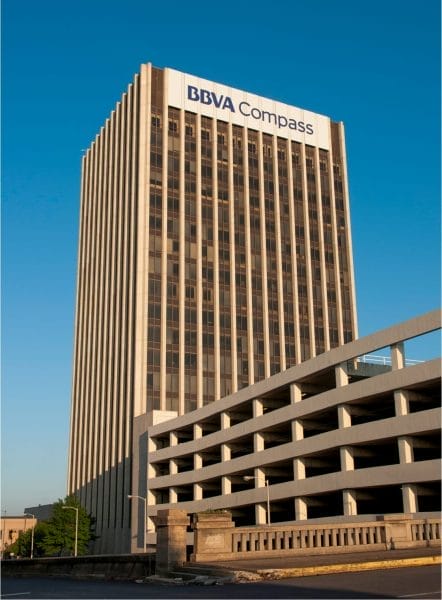

BBVA Compass Bank

Birmingham remains home to several of the nation’s largest steelmakers, including U.S. Steel, McWane, and Nucor and is also host to bioscience and technology development and some of the nation’s top construction and engineering firms. Birmingham is also headquarters for the engineering and technical services divisions of several power companies, including Alabama Power Company, ENERGEN Corporation, and SONAT. The Birmingham metropolitan area is Alabama’s largest commercial center and is currently one of the nation’s largest banking centers, serving as headquarters for Regions Financial Corporation. The overall banking structure in the city recently has been altered. Compass Bancshares, which still has headquarters in Birmingham, is now part of Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA), a worldwide financial services group based in Bilbao, Spain. Wachovia, which had a regional office in Birmingham, is now part of Wells Fargo as a result of financial trouble during the banking crisis of 2008.

BBVA Compass Bank

Birmingham remains home to several of the nation’s largest steelmakers, including U.S. Steel, McWane, and Nucor and is also host to bioscience and technology development and some of the nation’s top construction and engineering firms. Birmingham is also headquarters for the engineering and technical services divisions of several power companies, including Alabama Power Company, ENERGEN Corporation, and SONAT. The Birmingham metropolitan area is Alabama’s largest commercial center and is currently one of the nation’s largest banking centers, serving as headquarters for Regions Financial Corporation. The overall banking structure in the city recently has been altered. Compass Bancshares, which still has headquarters in Birmingham, is now part of Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA), a worldwide financial services group based in Bilbao, Spain. Wachovia, which had a regional office in Birmingham, is now part of Wells Fargo as a result of financial trouble during the banking crisis of 2008.

Education

Miles College

The Birmingham City School System oversees a large number of public schools throughout the city. In addition to UAB, the city has two other major institutions of higher learning, Samford University and Birmingham-Southern College. Historically black Miles College and Miles Law School, Birmingham School of Law, Jefferson State Community College, and Lawson State Community College provide other educational opportunities in the Birmingham area. Southeastern Baptist College, a nondenominational four-year institution, also is located in Birmingham. Daniel Payne College, which was established in Selma in 1889 by the African Methodist Episcopal Church, relocated to Birmingham for financial reasons in 1922. It closed in 1977.

Miles College

The Birmingham City School System oversees a large number of public schools throughout the city. In addition to UAB, the city has two other major institutions of higher learning, Samford University and Birmingham-Southern College. Historically black Miles College and Miles Law School, Birmingham School of Law, Jefferson State Community College, and Lawson State Community College provide other educational opportunities in the Birmingham area. Southeastern Baptist College, a nondenominational four-year institution, also is located in Birmingham. Daniel Payne College, which was established in Selma in 1889 by the African Methodist Episcopal Church, relocated to Birmingham for financial reasons in 1922. It closed in 1977.

Transportation

Birmingham is crossed by an extensive network of highways and roadways: Interstates 65, 20, 59, and 459; and U.S. Highways 31, 280, 11, and 78. Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport is the state’s largest and busiest airport, with seven major airlines offering daily flights to many major cities in the United States. Birmingham also has an Amtrak station that provides rail service to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charlotte, Atlanta, and New Orleans. The Metro Area Express (MAX) Bus System is Birmingham’s major inner-city bus system with natural-gas trolleys and electric buses.

Events and Places of Interest

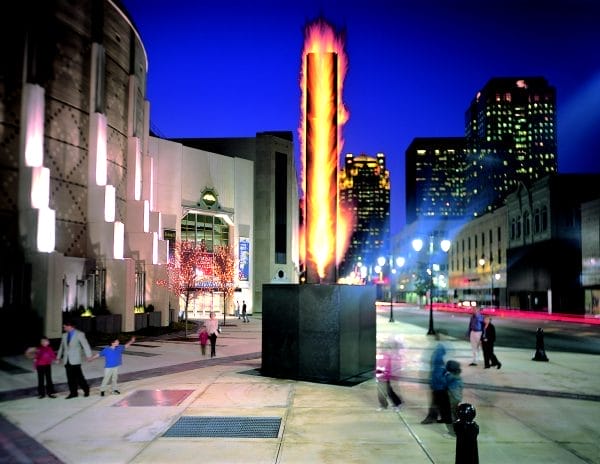

McWane Science Center

Birmingham’s hallmark attraction is the towering statue of Vulcan that overlooks the city from the top of Red Mountain. Italian sculptor Guiseppe Moretti constructed Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and metalworking, in 1904 to serve as a fitting symbol of the industrial city for the St. Louis World’s Fair. In 2004, after a four-year renovation, Vulcan Park reopened to the public and welcomed more than 100,000 visitors its first year. The downtown Civil Rights District also draws many tourists to the Civil Rights Institute, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, and Kelly Ingram Park. Other nearby attractions include the McWane Science Center, Arlington Antebellum Home and Gardens, the Birmingham Museum of Art, the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame, the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, the Southern Museum of Flight, the Alabama Theatre, the Sloss Furnaces Historic Landmark, the Birmingham Zoo, Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum, and the Birmingham Botanical Gardens. Other outdoor recreation areas include Oak Mountain State Park, Railroad Park, and Red Mountain Park. The corner of 20th Street and 1st Avenue North in the city is popularly known as “The Heaviest Corner on Earth” after a 1911 magazine article on the construction of the last of four large buildings at the site.

McWane Science Center

Birmingham’s hallmark attraction is the towering statue of Vulcan that overlooks the city from the top of Red Mountain. Italian sculptor Guiseppe Moretti constructed Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and metalworking, in 1904 to serve as a fitting symbol of the industrial city for the St. Louis World’s Fair. In 2004, after a four-year renovation, Vulcan Park reopened to the public and welcomed more than 100,000 visitors its first year. The downtown Civil Rights District also draws many tourists to the Civil Rights Institute, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, and Kelly Ingram Park. Other nearby attractions include the McWane Science Center, Arlington Antebellum Home and Gardens, the Birmingham Museum of Art, the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame, the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, the Southern Museum of Flight, the Alabama Theatre, the Sloss Furnaces Historic Landmark, the Birmingham Zoo, Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum, and the Birmingham Botanical Gardens. Other outdoor recreation areas include Oak Mountain State Park, Railroad Park, and Red Mountain Park. The corner of 20th Street and 1st Avenue North in the city is popularly known as “The Heaviest Corner on Earth” after a 1911 magazine article on the construction of the last of four large buildings at the site.

Rickwood Field

Boasting the third-longest golf course in the world, the Renaissance Birmingham Ross Bridge Golf Resort & Spa, located just a few miles southwest of downtown Birmingham, features an 8,194-yard Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail course, which hosts the Regions Charity Classic, a stop on the PGA Seniors golf tour. Birmingham is also home to the Birmingham Barons, a minor league affiliate of the Chicago White Sox. Rickwood Field, home of the Barons from 1910-1987, is the nation’s oldest baseball park. Legion Field, built in 1926, has been the host to memorable sporting events over the years, including many of the annual Iron Bowl contests between the University of Alabama and Auburn University as well as games by the University of Alabama at Birmingham; the Southeastern Conference and Southwestern Athletic Conference Championship Football Games; bowl games, pro football games, and soccer matches during the 1996 Summer Olympics.

Rickwood Field

Boasting the third-longest golf course in the world, the Renaissance Birmingham Ross Bridge Golf Resort & Spa, located just a few miles southwest of downtown Birmingham, features an 8,194-yard Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail course, which hosts the Regions Charity Classic, a stop on the PGA Seniors golf tour. Birmingham is also home to the Birmingham Barons, a minor league affiliate of the Chicago White Sox. Rickwood Field, home of the Barons from 1910-1987, is the nation’s oldest baseball park. Legion Field, built in 1926, has been the host to memorable sporting events over the years, including many of the annual Iron Bowl contests between the University of Alabama and Auburn University as well as games by the University of Alabama at Birmingham; the Southeastern Conference and Southwestern Athletic Conference Championship Football Games; bowl games, pro football games, and soccer matches during the 1996 Summer Olympics.

Further Reading

- Armes, Ethel. The Story of Coal and Iron in Alabama. 1910. Reprint, Leeds, Ala.: Beechwood Books, 1987.

- Atkins, Leah Rawls. The Valley and the Hills: An Illustrated History of Birmingham & Jefferson County. 1981. Reprint, Tarzana, Calif.: Preferred Marketing and the Birmingham Public Library, 1996.

- Bennett, James R. Historic Birmingham & Jefferson County: An Illustrated History. San Antonio, Tex.: Historical Pub. Network, 2008.

- Caldwell, H. M. History of the Elyton Land Company and Birmingham, Alabama. Birmingham: Caldwell, 1892.

- McMillan, Malcolm C. Yesterday’s Birmingham. Miami: E.A. Seeman Publishing, 1975.

External Links

- City of Birmingham

- Birmingham City Schools

- Jefferson County

- Birmingham Public Library

- Greater Birmingham Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Birmingham Business Alliance

- Birmingham Civil Rights Institute

- University of Alabama at Birmingham

- Samford University

- Birmingham-Southern College

- Miles College

- Birmingham School of Law

- Jefferson State Community College

- Lawson State Community College

- Southeastern Baptist College

- Encycylopedia of Southern Jewish Communities

- Birmingham Zoo

- Birmingham Museum of Art

- Ruffner Mountain

- Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark

- Rickwood Field

- Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail: Ross Bridge

- Railroad Park

- Red Mountain Park

- Birmingham Botanical Gardens