Traditional Music

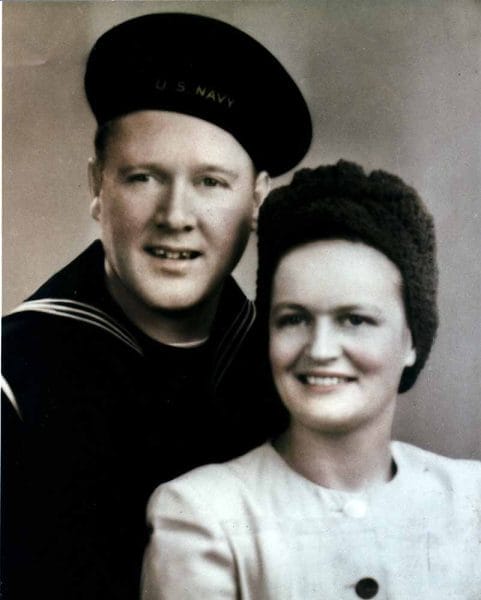

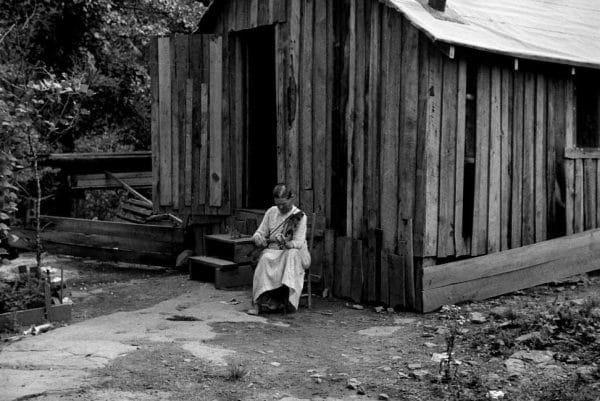

Mary McLean, Skyline Farms, 1937

Alabama has long been considered by folksong collectors as a state rich in traditional music. This is particularly a result of the waves of Scots-Irish and African peoples that populated the region during the nineteenth century, whose musical traditions were sustained by the enduring agricultural economy and by their relative cultural stability. When twentieth-century folksong collectors and recording-company talent scouts visited the state, they found a wealth of traditional music still embedded in community social entertainment, religious worship, and communal labor. Their collections long defined the breadth and character of traditional music in Alabama.

Mary McLean, Skyline Farms, 1937

Alabama has long been considered by folksong collectors as a state rich in traditional music. This is particularly a result of the waves of Scots-Irish and African peoples that populated the region during the nineteenth century, whose musical traditions were sustained by the enduring agricultural economy and by their relative cultural stability. When twentieth-century folksong collectors and recording-company talent scouts visited the state, they found a wealth of traditional music still embedded in community social entertainment, religious worship, and communal labor. Their collections long defined the breadth and character of traditional music in Alabama.

Later, as the economy diversified beyond its agricultural roots, and as suburbs and shopping malls came to redefine the landscape, musical traditions adapted. The first adaptation was in the major industries, such as the steel mills of Bessemer and the docks of Mobile Bay, where proximity and common experience provided a context for the formation of musical culture. As work and leisure became less communal, traditional music—in community festivals and other recreational events—remained important catalysts for social reaffirmation. More recently, as mass communication and travel have brought Americans closer together, traditional music has served as a means to carve out distinctions, to define what it means to be an Alabamian. Thus, it is common now to find music engaged as heritage, invoking its historical roots as a means to achieve distinctive cultural identity.

In popular usage, the term traditional music is generally defined as the long-standing musical practices of communities and informal social groups. In this sense, traditional music is seen as an expression of the most important concerns of the community. Originally, this term was applied only to rural and agricultural music, as opposed to formal music taught in schools and academies or distributed on recorded media. Today, the term embraces all music that arises from and is pertinent to social experience.

Secular Entertainment

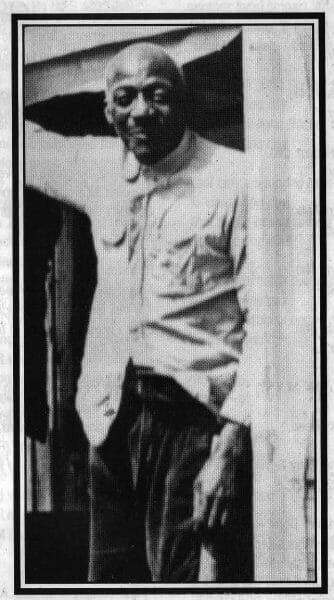

Charlie Stripling

Secular entertainment provided venues for the most visible forms of traditional music. Among the Scots-Irish, the fiddle took center-stage in dance bands, fiddle contests, and informal entertainment. Fiddlers played a variety of dance and song tunes, but the most important were the dance tunes from the fiddle tradition of the British Isles. The banjo was brought to Alabama by enslaved Africans and became an important component of African American music. Early banjos were made from skins stretched over gourds and existed in African American traditional music long before their nineteenth-century introduction into the Scots-Irish tradition.

Charlie Stripling

Secular entertainment provided venues for the most visible forms of traditional music. Among the Scots-Irish, the fiddle took center-stage in dance bands, fiddle contests, and informal entertainment. Fiddlers played a variety of dance and song tunes, but the most important were the dance tunes from the fiddle tradition of the British Isles. The banjo was brought to Alabama by enslaved Africans and became an important component of African American music. Early banjos were made from skins stretched over gourds and existed in African American traditional music long before their nineteenth-century introduction into the Scots-Irish tradition.

The addition of the banjo gave rise to fiddle ensembles known as string bands. Later, guitars and mandolins were added, especially in the late nineteenth century as they became available from manufacturers through mail-order catalogs. Homemade instruments were also important and were made from household implements such as spoons, washboards, and washtubs. Early string-band music was a feature of both European American and African American society, but it was sustained primarily among European Americans. In the 1920s, string bands were an important part of the development of the commercial country music industry. Alabama fiddlers Joe Lee and Charlie Stripling were influential during this era, and instrument maker Arlin Moon, of Cullman County, gained widespread fame for his fiddles, guitars, mandolins, and banjos. The current revival of “old-time music,” with Birmingham as an important center, deliberately draws its stylistic cues from this period.

Off-Stage Jam Session

In the post-World War II era, string-band music was reborn as bluegrass, which retained many stylistic features of pre-war tradition. Bluegrass differed chiefly in the introduction of a new banjo style, with three-finger upstrokes using fingerpicks rather than the pre-war down-stroking, or “frailing,” style. Fiddle music and contests also continued in popularity after World War II and are still beloved musical traditions in Alabama. The annual Tennessee Valley Old-Time Fiddlers Convention in Athens has achieved national prominence. In the latter half of the twentieth century, a subculture developed around fiddle contests, as did other subcultures, separately, around bluegrass music and old-time music.

Off-Stage Jam Session

In the post-World War II era, string-band music was reborn as bluegrass, which retained many stylistic features of pre-war tradition. Bluegrass differed chiefly in the introduction of a new banjo style, with three-finger upstrokes using fingerpicks rather than the pre-war down-stroking, or “frailing,” style. Fiddle music and contests also continued in popularity after World War II and are still beloved musical traditions in Alabama. The annual Tennessee Valley Old-Time Fiddlers Convention in Athens has achieved national prominence. In the latter half of the twentieth century, a subculture developed around fiddle contests, as did other subcultures, separately, around bluegrass music and old-time music.

Fiddle music and its stylistic kin have long been associated with community events and outdoor celebrations. The earliest forms were events such as political rallies, Fourth-of-July celebrations, and harvest festivals. Beginning in the 1950s, Alabamians organized outdoor music festivals around heritage themes and particular styles of music. Warren Musgrove’s gospel and bluegrass festival at Horse Pens 40 park near Steele, begun in 1958, was influential as an outdoor traditional music venue.

Delmore Brothers

Ballads (narrative folksongs) and other types of folksong were also important traditional music forms and were associated primarily with domestic performance. According to musicologists Byron Arnold and Ray B. Browne, Alabama’s traditional European American musicians favored a variety of folksong types, including traditional ballads, parlor songs, and lullabies. Traditional folksongs also influenced the development of commercial country music. Alabama musicians played an important role in the evolution of both the solo vocalist and performer, as embodied by Hank Williams Sr. of Georgiana, and the distinctive style of country duet singing made popular by the Delmore Brothers of Elkmont and the Louvin Brothers of Henagar. The Boaz group the Maddox Brothers and Rose, who migrated to California during the Great Depression, were also pioneers in country music performance.

Delmore Brothers

Ballads (narrative folksongs) and other types of folksong were also important traditional music forms and were associated primarily with domestic performance. According to musicologists Byron Arnold and Ray B. Browne, Alabama’s traditional European American musicians favored a variety of folksong types, including traditional ballads, parlor songs, and lullabies. Traditional folksongs also influenced the development of commercial country music. Alabama musicians played an important role in the evolution of both the solo vocalist and performer, as embodied by Hank Williams Sr. of Georgiana, and the distinctive style of country duet singing made popular by the Delmore Brothers of Elkmont and the Louvin Brothers of Henagar. The Boaz group the Maddox Brothers and Rose, who migrated to California during the Great Depression, were also pioneers in country music performance.

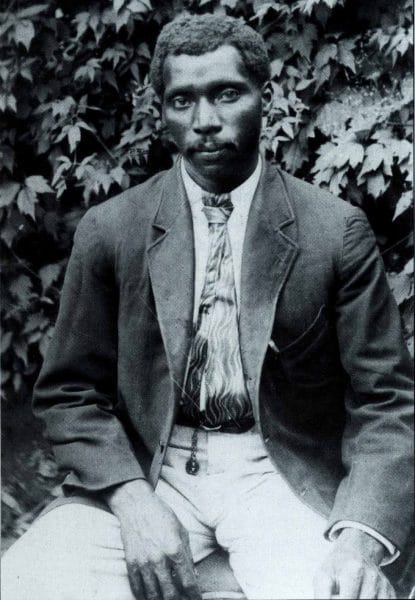

Dock Reed

The earliest African American secular music consisted of chants and field hollers, with stylistic traits that trace back to traditional musics of Africa. Adele “Vera” Hall and Dock Reed, of Sumter County, were the most celebrated performers of this type of music, and they were featured prominently in the collections of musicologists John Lomax, Alan Lomax, and Harold Courlander. By the end of the nineteenth century, African American secular music styles had coalesced into an influential new form called the blues, which wedded African musical traditions with popular European musical instruments such as guitar and piano. Blues became a staple of African American secular life and was associated with performances in small clubs called juke joints. Blues also was adapted for stage performance in minstrel and traveling shows and developed an urban style associated with theatrical performance. During the 1920s, commercial record companies popularized both blues forms, sometimes distinguished as urban blues and country blues.

Dock Reed

The earliest African American secular music consisted of chants and field hollers, with stylistic traits that trace back to traditional musics of Africa. Adele “Vera” Hall and Dock Reed, of Sumter County, were the most celebrated performers of this type of music, and they were featured prominently in the collections of musicologists John Lomax, Alan Lomax, and Harold Courlander. By the end of the nineteenth century, African American secular music styles had coalesced into an influential new form called the blues, which wedded African musical traditions with popular European musical instruments such as guitar and piano. Blues became a staple of African American secular life and was associated with performances in small clubs called juke joints. Blues also was adapted for stage performance in minstrel and traveling shows and developed an urban style associated with theatrical performance. During the 1920s, commercial record companies popularized both blues forms, sometimes distinguished as urban blues and country blues.

W. C. Handy, ca. 1940s

Alabama’s most celebrated blues proponent was W. C. Handy of Florence, who earned the title “the Father of the Blues” during the Progressive Era. Trained in the classical tradition, he worked as a band and choral director and toured extensively with African American ensembles. Handy had a profound grasp of the musical and cultural significance of the blues, and his compositions and promotional efforts brought blues into prominence as a legitimate American cultural form. Florence celebrates his life and work with its annual W. C. Handy Music Festival. Blues is most often associated with the Mississippi Delta, and that region was deeply influential in fostering urban blues traditions and providing the foundation for rock and roll. But Alabama has made significant contributions to this music form, and the Alabama Blues Project now serves as the organizational hub of a modern-day blues revival in the state.

W. C. Handy, ca. 1940s

Alabama’s most celebrated blues proponent was W. C. Handy of Florence, who earned the title “the Father of the Blues” during the Progressive Era. Trained in the classical tradition, he worked as a band and choral director and toured extensively with African American ensembles. Handy had a profound grasp of the musical and cultural significance of the blues, and his compositions and promotional efforts brought blues into prominence as a legitimate American cultural form. Florence celebrates his life and work with its annual W. C. Handy Music Festival. Blues is most often associated with the Mississippi Delta, and that region was deeply influential in fostering urban blues traditions and providing the foundation for rock and roll. But Alabama has made significant contributions to this music form, and the Alabama Blues Project now serves as the organizational hub of a modern-day blues revival in the state.

Also in the 1950s, the musical style known as rhythm and blues (R&B) emerged, with jazz and gospel influences. Alabama’s most notable interpreter of this style was Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton of Montgomery, noted as the first to record the song “Hound Dog,” later made famous by Elvis Presley. Other postwar performers, such as Percy Sledge of Colbert County, adopted a style that blended gospel influences and entered the crossover market known as country soul music. The Great Migration in the decades preceding the 1950s resulted in the transplanting of southern African American musical traditions to northern cities, where they emerged as postwar urban styles associated with soul music and Motown. Notable Alabama-born Motown performers were Martha Reeves of Eufaula and Wilson Pickett of Prattville.

Excelsior Band

Dixieland jazz, commonly associated with New Orleans, has played a role in Alabama’s traditional music history. Of special importance are the Gulf Coast Mardi Gras celebrations and the tradition of brass bands that perform in parades. Among Alabama’s most accomplished bands are the Excelsior Band, which dates to 1883, and the Bay City Brass Band, both of Mobile.

Excelsior Band

Dixieland jazz, commonly associated with New Orleans, has played a role in Alabama’s traditional music history. Of special importance are the Gulf Coast Mardi Gras celebrations and the tradition of brass bands that perform in parades. Among Alabama’s most accomplished bands are the Excelsior Band, which dates to 1883, and the Bay City Brass Band, both of Mobile.

Religious Folk Music

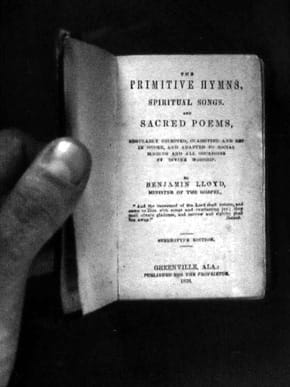

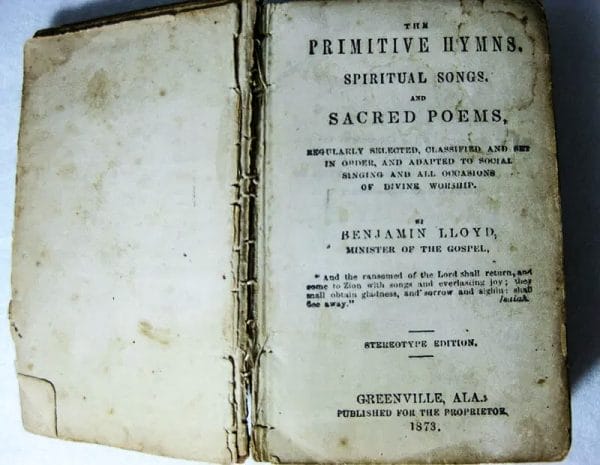

The Primitive Hymns

Alabama’s religious music traditions predate the establishment and development of official denominational hymnals and derive from traditions that came to North America in the eighteenth century. The earliest European American churches used hymn books that contained only lyrics that worshippers sang to a repertoire of memorized tunes. Singing from text-only hymn books largely disappeared with the adoption of printed music, but Alabama retains a vibrant hymn-singing tradition based on the book Primitive Hymns, compiled in 1841 by Benjamin Lloyd of Chambers County. The book has never gone out of print and is used by several Primitive Baptist associations in sections of the eastern United States. In the late-nineteenth century, the Sipsey River Association of African American Primitive Baptist Churches adopted the book, and it is still used by some congregations there today.

The Primitive Hymns

Alabama’s religious music traditions predate the establishment and development of official denominational hymnals and derive from traditions that came to North America in the eighteenth century. The earliest European American churches used hymn books that contained only lyrics that worshippers sang to a repertoire of memorized tunes. Singing from text-only hymn books largely disappeared with the adoption of printed music, but Alabama retains a vibrant hymn-singing tradition based on the book Primitive Hymns, compiled in 1841 by Benjamin Lloyd of Chambers County. The book has never gone out of print and is used by several Primitive Baptist associations in sections of the eastern United States. In the late-nineteenth century, the Sipsey River Association of African American Primitive Baptist Churches adopted the book, and it is still used by some congregations there today.

The early religious music of African Americans reflects their widespread adoption of Christianity, with evangelical conversion as a metaphorical spiritual liberation that contrasted sharply with the harsh reality of everyday life in the South. Worshippers incorporated African musical and choreographic elements into their services that became distinctive features of African American Christianity. The spiritual—which blended various influences from African American music with the theological and musical artifacts of Christianity—was the chief sacred musical expression from this period. In the 1870s, the spiritual was introduced on the concert stage by such groups as the Fisk Jubilee Singers, providing an influential performance model and reinforcing, in their “Jubilee” name, references to liberation theology. Collectors such as Byron Arnold, Robert Sonkin, Alan Lomax, and Harold Courlander, often with assistance from Sumter County native Ruby Pickens Tartt, documented examples of spirituals during their travels.

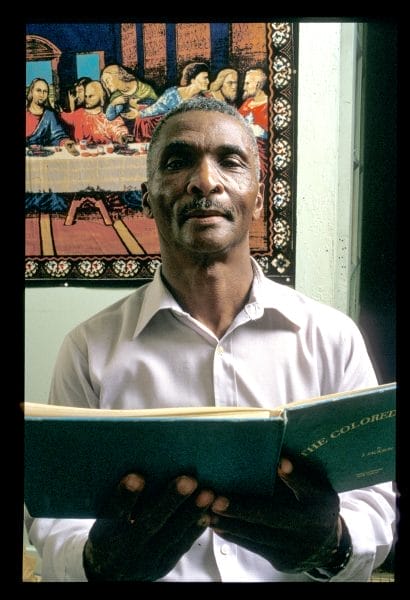

Henry Japeth Jackson

The most distinctive tradition of religious folk music in Alabama is Sacred Harp singing, also known as fasola or shape-note singing. This group vocal style is sung from tunebooks printed with accompanying symbols, called shape notes, and is taught in traditional venues called singing schools. The Sacred Harp tradition came to Alabama with the Denson family, who moved to Cleburne County in the 1850s. Brothers Seaborn McDaniel Denson (1854-1936) and Thomas Jackson Denson (1863-1935), of Cleburne and Winston Counties, taught Sacred Harp singing in north Alabama and produced their important revision of The Sacred Harp, a tunebook first published in 1844. In 1902, W. M. Cooper of Dothan introduced the Cooper Revision of the book that became established in the Southeast. In 1934, Judge Jackson of Ozark compiled The Colored Sacred Harp, and the book became established among African American singers of that region. Bibb County singers adopted the South Carolina tunebook Christian Harmony, and Alabama singers revised the book in 1958. Alabama has become an important repository for this once-national tradition and attracts followers from all over the world. Many attend the annual National Sacred Harp Singing Convention in Birmingham as well as other singings held throughout the state.

Henry Japeth Jackson

The most distinctive tradition of religious folk music in Alabama is Sacred Harp singing, also known as fasola or shape-note singing. This group vocal style is sung from tunebooks printed with accompanying symbols, called shape notes, and is taught in traditional venues called singing schools. The Sacred Harp tradition came to Alabama with the Denson family, who moved to Cleburne County in the 1850s. Brothers Seaborn McDaniel Denson (1854-1936) and Thomas Jackson Denson (1863-1935), of Cleburne and Winston Counties, taught Sacred Harp singing in north Alabama and produced their important revision of The Sacred Harp, a tunebook first published in 1844. In 1902, W. M. Cooper of Dothan introduced the Cooper Revision of the book that became established in the Southeast. In 1934, Judge Jackson of Ozark compiled The Colored Sacred Harp, and the book became established among African American singers of that region. Bibb County singers adopted the South Carolina tunebook Christian Harmony, and Alabama singers revised the book in 1958. Alabama has become an important repository for this once-national tradition and attracts followers from all over the world. Many attend the annual National Sacred Harp Singing Convention in Birmingham as well as other singings held throughout the state.

Speer Family

In the late-nineteenth century, gospel music became established in Alabama. Although closely related, European American and African American styles incorporated different cultural influences and were affiliated with separate worship and musical traditions. The European American gospel style arose when composers began experimenting with modern adaptations of shape-note harmony—introducing such devices as key modulations, close harmony, evangelical textual themes, and, later, quartet performance, gospel conventions with singing competitions, and performances in evangelical churches and on radio. Alabama has produced many notable performing gospel ensembles, including the Thrasher Brothers of Heflin, the Goodman Family of Sand Mountain, and the Speer Family of Double Springs. Important Alabama gospel composers include O. A. Parris of Jasper, G. T. “Dad” Speer of Double Springs, and J. L. Roper of Hayden. Legendary songwriter J. R. “Pap” Baxter of Lebanon co-founded the Stamps-Baxter Publishing Company in 1926, one of the leading gospel music publishing houses. The Sullivan Family of St. Stephens, has achieved prominence in the “bluegrass gospel” style of performance, which features gospel music set to bluegrass instrumentation, and Jake Hess of Limestone County. In 1986, Truman Glassco of Horton organized the Alabama School of Gospel Music as a means to reenergize the tradition in the state.

Speer Family

In the late-nineteenth century, gospel music became established in Alabama. Although closely related, European American and African American styles incorporated different cultural influences and were affiliated with separate worship and musical traditions. The European American gospel style arose when composers began experimenting with modern adaptations of shape-note harmony—introducing such devices as key modulations, close harmony, evangelical textual themes, and, later, quartet performance, gospel conventions with singing competitions, and performances in evangelical churches and on radio. Alabama has produced many notable performing gospel ensembles, including the Thrasher Brothers of Heflin, the Goodman Family of Sand Mountain, and the Speer Family of Double Springs. Important Alabama gospel composers include O. A. Parris of Jasper, G. T. “Dad” Speer of Double Springs, and J. L. Roper of Hayden. Legendary songwriter J. R. “Pap” Baxter of Lebanon co-founded the Stamps-Baxter Publishing Company in 1926, one of the leading gospel music publishing houses. The Sullivan Family of St. Stephens, has achieved prominence in the “bluegrass gospel” style of performance, which features gospel music set to bluegrass instrumentation, and Jake Hess of Limestone County. In 1986, Truman Glassco of Horton organized the Alabama School of Gospel Music as a means to reenergize the tradition in the state.

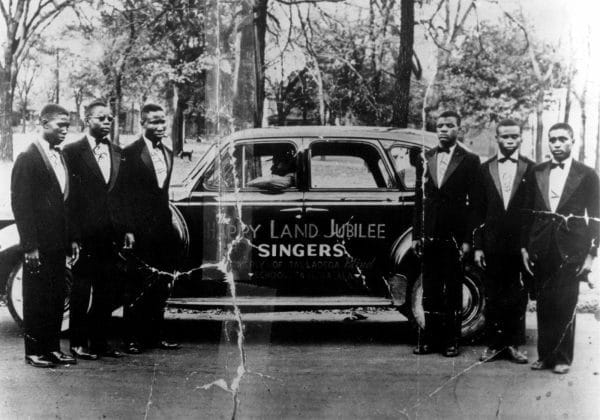

Happy Land Jubilee Singers

African American gospel music is related to European American gospel tradition mainly in its adoption of the predominant stylistic traits and its association with evangelical religion. It is considered a twentieth-century modernization of the spiritual, the chief musical form of early African American Christianity, and it ultimately developed into two forms. As a form of worship, it evolved from congregational singing, featuring call-and-response musical patterns, into performances by choirs. By the mid-twentieth century, gospel worship had developed a distinctive form associated with urban churches, with large choirs and virtuoso solo vocalists. A second gospel music form was the gospel quartet, an ensemble style featuring a capella singing, close harmony, precision arrangements, and performance in both display and worship settings. Alabama is noted for its virtuoso ensembles: in the 1920s the Birmingham area produced groups such as the Sterling Jubilee Singers. From the quartet tradition emerged important ensembles such as the Blind Boys of Alabama (which originated at the Alabama School for the Deaf and Blind in Talladega), Dorothy Love Coates and the Original Gospel Harmonettes of Birmingham, and contemporary groups like the Birmingham Sunlights and Take 6.

Happy Land Jubilee Singers

African American gospel music is related to European American gospel tradition mainly in its adoption of the predominant stylistic traits and its association with evangelical religion. It is considered a twentieth-century modernization of the spiritual, the chief musical form of early African American Christianity, and it ultimately developed into two forms. As a form of worship, it evolved from congregational singing, featuring call-and-response musical patterns, into performances by choirs. By the mid-twentieth century, gospel worship had developed a distinctive form associated with urban churches, with large choirs and virtuoso solo vocalists. A second gospel music form was the gospel quartet, an ensemble style featuring a capella singing, close harmony, precision arrangements, and performance in both display and worship settings. Alabama is noted for its virtuoso ensembles: in the 1920s the Birmingham area produced groups such as the Sterling Jubilee Singers. From the quartet tradition emerged important ensembles such as the Blind Boys of Alabama (which originated at the Alabama School for the Deaf and Blind in Talladega), Dorothy Love Coates and the Original Gospel Harmonettes of Birmingham, and contemporary groups like the Birmingham Sunlights and Take 6.

Labor Music

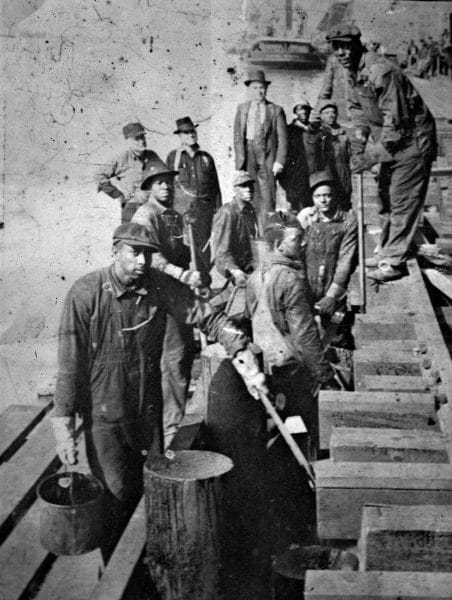

Gandy Dancers

Alabama’s earliest labor music included agricultural songs of the Scots-Irish and African American field hollers and work songs, all of which appeared in early folklore collections. With industrialization, new song forms arose among the primarily African American workers in coal mines, at the Mobile docks, on the railroads, and in the Birmingham steel mills. African American railroad workers, known as gandy dancers, developed a call-and-response chant that was synchronized to the timing of group manual track labor. African American steel workers developed an exceptional musical culture featuring protest songs sung by quartets. The songs and tunes of the various labor genres reflected the hardships of or provided entertaining relief from strenuous and repetitive manual labor.

Gandy Dancers

Alabama’s earliest labor music included agricultural songs of the Scots-Irish and African American field hollers and work songs, all of which appeared in early folklore collections. With industrialization, new song forms arose among the primarily African American workers in coal mines, at the Mobile docks, on the railroads, and in the Birmingham steel mills. African American railroad workers, known as gandy dancers, developed a call-and-response chant that was synchronized to the timing of group manual track labor. African American steel workers developed an exceptional musical culture featuring protest songs sung by quartets. The songs and tunes of the various labor genres reflected the hardships of or provided entertaining relief from strenuous and repetitive manual labor.

Native American Musical Traditions

Alabama’s Native American musical traditions were largely removed from the state with the forced expulsion of the Creeks, Cherokees, Choctaws, and Chickasaws, among others, in the early nineteenth century. Those who remained were not inclined to maintain a visible cultural presence. Today, there is a revival underway, however, with many Alabamians reclaiming tribal identity. Tribal representatives from removal areas encourage and participate in the revival of these musical traditions in Alabama. Contemporary Alabama tribes such as the MOWA band of Choctaw in Mount Vernon and the Poarch Creeks in Atmore, host annual powwows that include music and dance.

Folk Music of Other Ethnicities

Although Africans and Scots-Irish have predominated in folksong collections, Alabama is a diverse state with music from many other cultural points of origin. The concentrations of early French settlers on the Gulf coast and nineteenth-century Germans in Cullman County would have included musical traditions, but this largely escaped the attention of folklorists and other observers. In recent decades, musical traditions have been documented among recent immigrant groups, especially where there are concentrated settlements and a disinclination to assimilate. Notable are Southeast Asians in the southwest coastal region of Alabama and Latin Americans who have settled throughout the state. Mariachi Garibaldi, a professional mariachi band has settled in Alabama and performs throughout the Southeast. The folk music of recent immigrants is an intriguing and fast-changing field that will undoubtedly receive more attention from future scholars.

Music Recordings

Further Reading

- Arnold, Byron. Folksongs of Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1950.

- Brackner, Joey, ed. Spirit of Steel: Music of the Mines, Railroads and Mills of the Birmingham District. Birmingham: Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark/Crane Hill Publishers, 1999.

- Browne, Ray Broadus. The Alabama Folk Lyric: A Study in Origins and Media of Dissemination. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1979.

- Cauthen, Joyce H. With Fiddle and Well-Rosined Bow: A History of Old-Time Fiddling in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.

- Cauthen, Joyce H., ed. Benjamin Lloyd’s Hymn Book: A Primitive Baptist Song Tradition. Montgomery: Alabama Folklife Association.

- Courlander, Harold. Negro Songs from Alabama. New York: Oak Publications, 1963.

- ———. Negro Folk Music of Alabama. 5 vols. New York: Folkways Records, 1950–1955.

- Halli, Robert. An Alabama Songbook: Ballads, Folksongs, and Spirituals Collected by Byron Arnold. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Lomax, Alan. Alabama: From Lullabies to Blues. Field Recordings from 1934-1940. Cambridge, Mass.: Rounder Records, 2001.

- Lomax, John. Field Recordings. Vol. 4, Mississippi and Alabama (1934-1942). Vienna, Austria: Document Records, 1997.

- Martin, Stephen H., ed. Alabama Folklife: Collected Essays. Birmingham: Alabama Folklife Association, 1989.

- Traditional Musics of Alabama. 4 vols. Montgomery: Alabama Center for Traditional Culture, 2001–2005.

- Willett, Henry, ed. In the Spirit: Alabama’s Sacred Music Traditions. Montgomery: Black Belt Press for the Alabama Folklife Association, 1995.