Selma to Montgomery March

The 1965 Selma to Montgomery march was the climactic event of the Selma voting rights demonstrations. It provided some of the most recognized imagery of the civil rights movement and sparked several infamous crimes. Its route is now a national historic trail, and re-enactors, some of whom took part in the original march, meet on important anniversaries to retrace the path of the original event.

Marching to Montgomery

In November 1964, the leadership of the Dallas County Voters League, the principal black civil-rights organization in Selma, persuaded Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to come to the city to assist in demonstrating against the Dallas County Board of Voting Registrars and what the league believed were the board’s discriminatory registration practices. The demonstrations, which began on January 18, 1965, produced rapidly escalating tensions in Selma, culminating in mass arrests by authorities under the direction of Sheriff James G. Clark, Jr. By February 5, more than 2,400 demonstrators had been jailed. As a result of litigation initiated by civil rights attorneys on January 22, however, U.S. District Judge Daniel H. Thomas of Mobile issued an injunction on February 4 listing in detail the non-discriminatory procedures that the Board of Registrars would be required to follow. After these procedures were implemented by the board on February 15, demonstrations in Selma dwindled in size, and the SCLC turned its attention to registration in nearby Perry, Wilcox, and Lowndes counties.

Marching to Montgomery

In November 1964, the leadership of the Dallas County Voters League, the principal black civil-rights organization in Selma, persuaded Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to come to the city to assist in demonstrating against the Dallas County Board of Voting Registrars and what the league believed were the board’s discriminatory registration practices. The demonstrations, which began on January 18, 1965, produced rapidly escalating tensions in Selma, culminating in mass arrests by authorities under the direction of Sheriff James G. Clark, Jr. By February 5, more than 2,400 demonstrators had been jailed. As a result of litigation initiated by civil rights attorneys on January 22, however, U.S. District Judge Daniel H. Thomas of Mobile issued an injunction on February 4 listing in detail the non-discriminatory procedures that the Board of Registrars would be required to follow. After these procedures were implemented by the board on February 15, demonstrations in Selma dwindled in size, and the SCLC turned its attention to registration in nearby Perry, Wilcox, and Lowndes counties.

Demonstrations began in Marion, the Perry County seat, on February 1 under the leadership of bricklayer Albert Turner, president of the Perry County Civic League. They culminated on the night of February 18 in a bloody riot initiated by state troopers and local police. Trooper J. Bonard Fowler shot black laborer Jimmie Lee Jackson in the stomach, and five other black marchers and three white reporters were hospitalized with various injuries. Jackson died in a Selma hospital on February 26.

Bloody Sunday

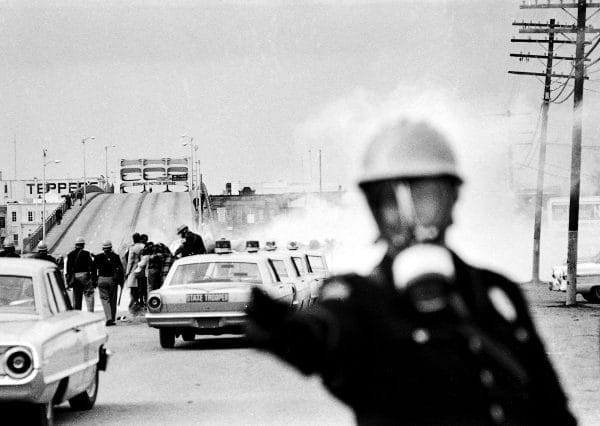

Infuriated by Jackson’s shooting, leaders of the SCLC and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) called on the black residents of Black Belt counties to march on the capitol in Montgomery, where the legislature was in special session, to demand statewide reforms in the voter-registration process. Tensions in Selma, which had begun to subside, were quickly re-ignited. On March 6, Gov. George C. Wallace Jr. forbade the march and ordered state troopers to prevent it. On the same day, a demonstration by white liberals led by Lutheran minister Joseph Ellwanger of Birmingham almost ended in a bloodbath. On Sunday, March 7, some 600 black protesters, led by SCLC’s Hosea Williams and SNCC’s John Lewis, undertook the march. As they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge over the Alabama River, they were blocked by a contingent of 65 troopers, 10 or more Dallas County sheriff’s deputies, and 15 mounted members of the sheriff’s deputized posse. Amidst billowing tear gas, the law enforcement personnel beat the marchers back across the bridge. Fifty-six black marchers were hospitalized, including organizer Amelia Boynton Robinson, though only 18 of them were hurt seriously enough to be kept overnight.

Bloody Sunday

Infuriated by Jackson’s shooting, leaders of the SCLC and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) called on the black residents of Black Belt counties to march on the capitol in Montgomery, where the legislature was in special session, to demand statewide reforms in the voter-registration process. Tensions in Selma, which had begun to subside, were quickly re-ignited. On March 6, Gov. George C. Wallace Jr. forbade the march and ordered state troopers to prevent it. On the same day, a demonstration by white liberals led by Lutheran minister Joseph Ellwanger of Birmingham almost ended in a bloodbath. On Sunday, March 7, some 600 black protesters, led by SCLC’s Hosea Williams and SNCC’s John Lewis, undertook the march. As they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge over the Alabama River, they were blocked by a contingent of 65 troopers, 10 or more Dallas County sheriff’s deputies, and 15 mounted members of the sheriff’s deputized posse. Amidst billowing tear gas, the law enforcement personnel beat the marchers back across the bridge. Fifty-six black marchers were hospitalized, including organizer Amelia Boynton Robinson, though only 18 of them were hurt seriously enough to be kept overnight.

King Speaks In Selma

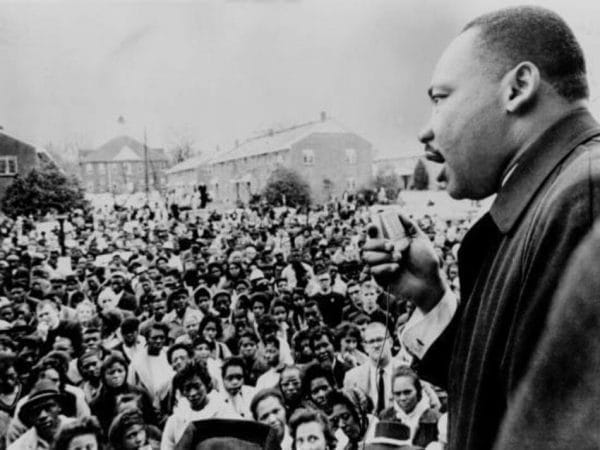

As a result of this event, which became known as “Bloody Sunday,” Martin Luther King issued a call for sympathetic Americans to join him in Selma to renew the march, and thousands flocked to the city, including many religious leaders. King’s attorneys filed suit in federal district court in Montgomery, seeking an injunction to forbid Wallace from interfering with the protest. U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. scheduled a hearing on the petition and in the meantime issued a restraining order against the demonstration. On March 9, King led 2,500 marchers across the Pettus Bridge to the point of the troopers’ Bloody Sunday attack and stopped. Hesitant to violate Judge Johnson’s order any further, King obeyed police instructions to turn the march around. As a result he found himself denounced both by segregationists, who believed that the march contravened the restraining order, and by civil-rights militants, especially members of SNCC, who believed that he should have defied it and continued to Montgomery. That night, three white ministers who had come to Selma to participate in the march were attacked by four white supremacists, and one of the ministers, Rev. James Reeb of Boston, died of his injuries two days later. Selma residents Elmer L. Cook, W. Stanley Hoggle, and N. O’Neal Hoggle were indicted in April for Reeb’s murder, but the following December an all-white Selma jury would acquit them.

King Speaks In Selma

As a result of this event, which became known as “Bloody Sunday,” Martin Luther King issued a call for sympathetic Americans to join him in Selma to renew the march, and thousands flocked to the city, including many religious leaders. King’s attorneys filed suit in federal district court in Montgomery, seeking an injunction to forbid Wallace from interfering with the protest. U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. scheduled a hearing on the petition and in the meantime issued a restraining order against the demonstration. On March 9, King led 2,500 marchers across the Pettus Bridge to the point of the troopers’ Bloody Sunday attack and stopped. Hesitant to violate Judge Johnson’s order any further, King obeyed police instructions to turn the march around. As a result he found himself denounced both by segregationists, who believed that the march contravened the restraining order, and by civil-rights militants, especially members of SNCC, who believed that he should have defied it and continued to Montgomery. That night, three white ministers who had come to Selma to participate in the march were attacked by four white supremacists, and one of the ministers, Rev. James Reeb of Boston, died of his injuries two days later. Selma residents Elmer L. Cook, W. Stanley Hoggle, and N. O’Neal Hoggle were indicted in April for Reeb’s murder, but the following December an all-white Selma jury would acquit them.

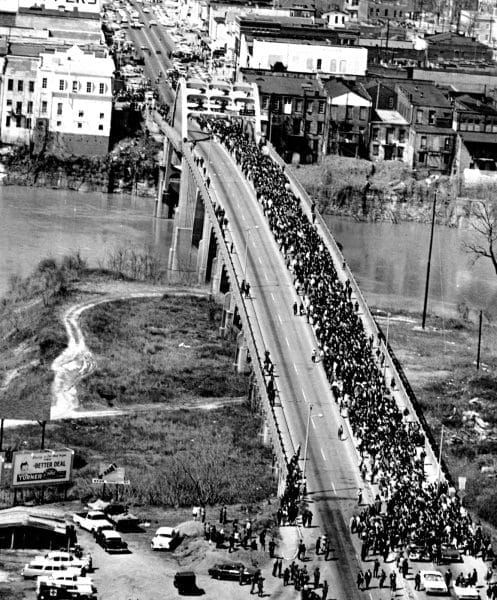

On March 17, after five days of testimony, Judge Johnson granted an order authorizing the march. On March 21, King led a diverse group of 8,000 demonstrators out of Selma under the protection of 2,000 National Guard troops and federal marshals. On the second and third days of the march, under the terms of Judge Johnson’s order, the marchers were reduced to a small number as they proceeded along the two-lane stretch of U.S. Highway 80 in Lowndes County. But as the march approached Montgomery, the number of demonstrators again swelled. On the final day, March 25, King addressed a throng of 25,000 from the front of the capitol and assured them that the elimination of white supremacy was near.

Crossing Edmund Pettus Bridge

On the night of that final day, a car containing four Birmingham Ku Klux Klansmen overtook one driven by Viola Gregg Liuzzo of Detroit, who had been ferrying demonstrators back to Selma from Montgomery. The Klansmen, angered because a young black man was seated beside Liuzzo on the front seat, murdered her. Three of the Klansmen, Collie Leroy Wilkins, Eugene Thomas, and William O. Eaton were indicted for the crime, on the testimony of the fourth, G. Thomas Rowe. Though they were acquitted of murder at their trials in state court in Hayneville, they were convicted in December 1965 in federal court in Montgomery of depriving Liuzzo of her civil right to life and sentenced to 10-year prison terms by Judge Johnson. They were the only persons responsible for any of the deaths related to the march to be punished.

Crossing Edmund Pettus Bridge

On the night of that final day, a car containing four Birmingham Ku Klux Klansmen overtook one driven by Viola Gregg Liuzzo of Detroit, who had been ferrying demonstrators back to Selma from Montgomery. The Klansmen, angered because a young black man was seated beside Liuzzo on the front seat, murdered her. Three of the Klansmen, Collie Leroy Wilkins, Eugene Thomas, and William O. Eaton were indicted for the crime, on the testimony of the fourth, G. Thomas Rowe. Though they were acquitted of murder at their trials in state court in Hayneville, they were convicted in December 1965 in federal court in Montgomery of depriving Liuzzo of her civil right to life and sentenced to 10-year prison terms by Judge Johnson. They were the only persons responsible for any of the deaths related to the march to be punished.

Selma to Montgomery March End

The national publicity that the march generated played a significant role in inducing the U.S. Congress to adopt the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which suspended the use of literacy tests as a requirement for voter registration and temporarily placed the registration process in certain obstinate areas, including Selma, in the hands of federal officials. On the other hand, the march infuriated racial conservatives. Rumors spread among them that the marchers’ nighttime encampments had been scenes of sexual licentiousness. Congressman William L. Dickinson of Montgomery repeated these claims on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives. For people disposed to believe such stories, the march became proof of the civil-rights movement’s moral bankruptcy. In addition, the march exacerbated tensions between SCLC and SNCC, whose workers resented the public focus on King. But in the minds of many Americans, chiefly blacks and northern white liberals, the Selma-to-Montgomery march joined the Boston Tea Party, the Gettysburg Address, and other well-known events as a pivotal moment in the nation’s progress toward full democracy and racial justice.

Selma to Montgomery March End

The national publicity that the march generated played a significant role in inducing the U.S. Congress to adopt the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which suspended the use of literacy tests as a requirement for voter registration and temporarily placed the registration process in certain obstinate areas, including Selma, in the hands of federal officials. On the other hand, the march infuriated racial conservatives. Rumors spread among them that the marchers’ nighttime encampments had been scenes of sexual licentiousness. Congressman William L. Dickinson of Montgomery repeated these claims on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives. For people disposed to believe such stories, the march became proof of the civil-rights movement’s moral bankruptcy. In addition, the march exacerbated tensions between SCLC and SNCC, whose workers resented the public focus on King. But in the minds of many Americans, chiefly blacks and northern white liberals, the Selma-to-Montgomery march joined the Boston Tea Party, the Gettysburg Address, and other well-known events as a pivotal moment in the nation’s progress toward full democracy and racial justice.

The Selma to Montgomery National Voting Rights Trail was created by an act of Congress in 1996, and the National Park Service operates the Selma Interpretive Center and the Lowndes County Interpretive Center as visitor’s centers for the trail.

Further Reading

- Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism and the Transformation of American Politics. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

- Garrow, David J. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. New York: William Morrow, 1986.

- Thornton, J. Mills, III. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham and Selma. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.