State of Alabama

Little River

Both in physical size and in population, Alabama has typically ranked near the middle of the 50 American states. The state’s 52,423 square miles are configured in a length of 330 miles and a width of 150 miles at their longest and widest expanse. Because multiple geological and topographical features intersect in the state (ranging from the Appalachian mountain chain in the northeast to the East Gulf Coastal Plain in the south), the state boasts a rich diversity of physiographic features and, consequently, among the greatest biological and geological diversity to be found in the United States. Rich in mineral wealth and flowing water, the state’s historic poverty cannot be attributed to lack of natural resources. Fiercely independent and resistant to outsiders, a portion of the state’s white population enslaved a population nearly its own size to promote plantation cotton cultivation and became fabulously wealthy in the process. The arrogance of that wealth factored into the decision to secede from the Union in 1861, with disastrous consequences. The death of perhaps a fifth of the prime-age white male population during the war, the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in capital with the emancipation of slaves, political control by a liberal outside power structure followed by the reinstitution of conservative white rule, and finally the establishment of a system of racial apartheid all shaped the state well into the twentieth century. So did the decline of cotton monoculture and the rise of industrialization together with the shift of economic activity from the Port of Mobile and river towns to inland and upland urban centers newly linked by railroads.

Little River

Both in physical size and in population, Alabama has typically ranked near the middle of the 50 American states. The state’s 52,423 square miles are configured in a length of 330 miles and a width of 150 miles at their longest and widest expanse. Because multiple geological and topographical features intersect in the state (ranging from the Appalachian mountain chain in the northeast to the East Gulf Coastal Plain in the south), the state boasts a rich diversity of physiographic features and, consequently, among the greatest biological and geological diversity to be found in the United States. Rich in mineral wealth and flowing water, the state’s historic poverty cannot be attributed to lack of natural resources. Fiercely independent and resistant to outsiders, a portion of the state’s white population enslaved a population nearly its own size to promote plantation cotton cultivation and became fabulously wealthy in the process. The arrogance of that wealth factored into the decision to secede from the Union in 1861, with disastrous consequences. The death of perhaps a fifth of the prime-age white male population during the war, the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in capital with the emancipation of slaves, political control by a liberal outside power structure followed by the reinstitution of conservative white rule, and finally the establishment of a system of racial apartheid all shaped the state well into the twentieth century. So did the decline of cotton monoculture and the rise of industrialization together with the shift of economic activity from the Port of Mobile and river towns to inland and upland urban centers newly linked by railroads.

Marching to Montgomery

A new constitution written in 1901 not only crushed rural political insurgency but also fixed the principles of the old conservative white regime into law. Disfranchising almost all African Americans and many poor and working-class whites, the constitution hardened class and racial divisions that remained in place until the civil rights movement of the 1960s and intervention by the U.S. Congress, the executive branch, and the federal courts. As both agriculture and then heavy manufacturing declined, and as Birmingham and Montgomery were paralyzed by racial conflict, the state lost its long challenge to lead the “New South” into modernization and national leadership. Decades of decline and decay finally gave way to renewal in the last quarter of the twentieth century. As African Americans were mainstreamed into politics, education, and economic life, cities such as Huntsville, Birmingham, Montgomery, and Mobile experienced a renaissance, the state thrived in a globalized world economy, and a new generation of socially enlightened entrepreneurs and their allies led the way toward racial reconciliation and educational modernization.

Marching to Montgomery

A new constitution written in 1901 not only crushed rural political insurgency but also fixed the principles of the old conservative white regime into law. Disfranchising almost all African Americans and many poor and working-class whites, the constitution hardened class and racial divisions that remained in place until the civil rights movement of the 1960s and intervention by the U.S. Congress, the executive branch, and the federal courts. As both agriculture and then heavy manufacturing declined, and as Birmingham and Montgomery were paralyzed by racial conflict, the state lost its long challenge to lead the “New South” into modernization and national leadership. Decades of decline and decay finally gave way to renewal in the last quarter of the twentieth century. As African Americans were mainstreamed into politics, education, and economic life, cities such as Huntsville, Birmingham, Montgomery, and Mobile experienced a renaissance, the state thrived in a globalized world economy, and a new generation of socially enlightened entrepreneurs and their allies led the way toward racial reconciliation and educational modernization.

- Founding Date: December 14, 1819

- Area: 52,423 square miles

- Population: 5,024,279 (2020 Census estimate)

- Major Highways: Interstates 10, 20, 22, 59, 65, and 85

- Capitol: Montgomery

- Largest City: Birmingham

Demographics

Alabama’s population according to 2020 Census estimates was 5,024,279. Approximately 67.5 percent identified themselves white, 26.6 as African American, 4.4 percent as Hispanic, 2.4 percent as two or more races, 1.4 percent as Asian, and 0.5 percent as Native American. The state’s median household income was $52,035, and per capita income was $28,934.

Employment

According to 2020 Census estimates, the workforce in Alabama was divided among the following industrial categories:

- Educational services, and health care and social assistance (22.7 percent)

- Manufacturing (14.2 percent)

- Retail trade (11.6 percent)

- Professional, scientific, administrative, and waste management services (9.6 percent)

- Arts, entertainment, and recreation, accommodation, and food services (8.3 percent)

- Construction (6.7 percent)

- Finance and insurance, and real estate and rental and leasing (5.6 percent)

- Public administration (5.5 percent)

- Transportation and warehousing, and utilities (5.5 percent)

- Other services, except public administration (4.9 percent)

- Wholesale trade (2.5 percent)

- Information (1.5 percent)

- Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, and extractive (1.4 percent)

Environment and Exploitation

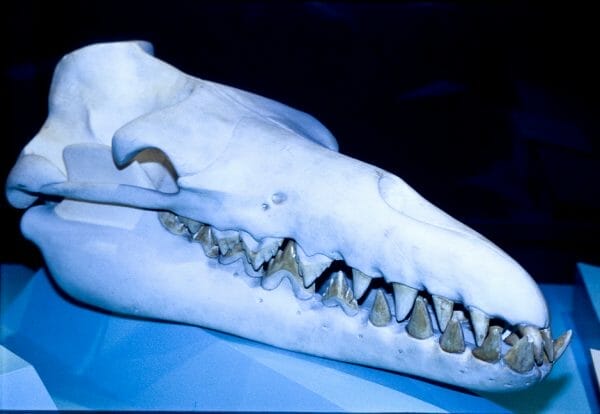

Long before humankind disturbed Alabama’s forests and streams, enormously powerful natural forces bent, broke, shaped, and reshaped its landscape. Seismic convulsions and shifting tectonic plates shoved mountains above the waters of ancient seas that reached north of Montgomery. As a result, the state contains the fossil remains of more ancient sea creatures and plants than any other state, dating back hundreds of millions of years. When the Alabama coastline reached well to the north of its current location, giant Cretaceous mosasaurs and the Paleogene Basilosaurus, a prehistoric whale and the state fossil, swam in the ancient seas.

Basilosaurus cetoides

As the continents shifted and ocean waters moved south toward the present-day Gulf of Mexico, deep valleys became the natural conduit for swiftly moving waters that cascaded over rocky bottoms, falling toward the sea. An estimated 10 percent of the fresh water that flows through the 48 continental United States courses through Alabama. In the hill country and mountain regions of eastern and northern Alabama, waters fall over rough limestone terrain, gouging caves and creating impressive falls. In south Alabama, the streams become languid. The Alabama River, the state’s largest, is the fourth largest river system in the United States based on discharge, emptying 62,500 cubic feet per second into Mobile Bay. Beneath the waters life thrives, supporting the most diverse array of mussels, snails, turtles, fish, and other aquatic life to be found anywhere in the nation. At one time, Alabama was home to 180 different species of mussels, accounting for two-thirds of all species found in North America, as well as 83 species of crayfish, the most of any state.

Basilosaurus cetoides

As the continents shifted and ocean waters moved south toward the present-day Gulf of Mexico, deep valleys became the natural conduit for swiftly moving waters that cascaded over rocky bottoms, falling toward the sea. An estimated 10 percent of the fresh water that flows through the 48 continental United States courses through Alabama. In the hill country and mountain regions of eastern and northern Alabama, waters fall over rough limestone terrain, gouging caves and creating impressive falls. In south Alabama, the streams become languid. The Alabama River, the state’s largest, is the fourth largest river system in the United States based on discharge, emptying 62,500 cubic feet per second into Mobile Bay. Beneath the waters life thrives, supporting the most diverse array of mussels, snails, turtles, fish, and other aquatic life to be found anywhere in the nation. At one time, Alabama was home to 180 different species of mussels, accounting for two-thirds of all species found in North America, as well as 83 species of crayfish, the most of any state.

Gulf Sturgeon Research

The Gulf sturgeon, one of the largest and most primitive fishes in the United States, was once abundant in Alabama’s rivers before dams prevented these fish from reaching their spawning areas upriver. When the Tombigbee and Alabama river systems join in south Alabama, they create one of the largest and most ecologically complex deltas in the nation. Second in size only to the Mississippi River Delta in Louisiana, the Mobile-Tensaw Delta (45 miles long and between 6 and 16 miles wide) is home to 500 identified plant species, 300 types of birds, 126 species of fish, 46 varieties of mammals, 69 species of reptiles, and 30 kinds of amphibians. Unfortunately, the state’s rapacious development, damming of rivers, chemical runoff from agricultural fields, and lack of concern for the environment have destroyed or threatened much of this priceless habitat. Alabama has not only the most diverse freshwater aquatic life of any state but also the highest extinction rate.

Gulf Sturgeon Research

The Gulf sturgeon, one of the largest and most primitive fishes in the United States, was once abundant in Alabama’s rivers before dams prevented these fish from reaching their spawning areas upriver. When the Tombigbee and Alabama river systems join in south Alabama, they create one of the largest and most ecologically complex deltas in the nation. Second in size only to the Mississippi River Delta in Louisiana, the Mobile-Tensaw Delta (45 miles long and between 6 and 16 miles wide) is home to 500 identified plant species, 300 types of birds, 126 species of fish, 46 varieties of mammals, 69 species of reptiles, and 30 kinds of amphibians. Unfortunately, the state’s rapacious development, damming of rivers, chemical runoff from agricultural fields, and lack of concern for the environment have destroyed or threatened much of this priceless habitat. Alabama has not only the most diverse freshwater aquatic life of any state but also the highest extinction rate.

Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge

The soils, rocks, trees and plants of Alabama are no less complex and amazing than its waters. Within its borders, Alabama has more than 190 mineral types, many of which played key roles in the state’s industrialization (coal, iron ore, limestone, clays, chalk, marble, quartz, copper, gold, and graphite). Forests covered the entire state when humans first arrived. They ranged from huge stands of mountain longleaf pine that grew amidst an open grassy understory to extensive and dense hardwood forests. The longleaf pine—unique for its dense core used for naval stores, lumber, railroad ties, and “heart-pine” floors—once constituted the most extensive ecosystem in North America (90 million acres); that acreage has now shrunk to less than 3 million. That forest nurtured a now-imperiled ecosystem of 35 species of amphibians, 56 types of reptiles,

Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge

The soils, rocks, trees and plants of Alabama are no less complex and amazing than its waters. Within its borders, Alabama has more than 190 mineral types, many of which played key roles in the state’s industrialization (coal, iron ore, limestone, clays, chalk, marble, quartz, copper, gold, and graphite). Forests covered the entire state when humans first arrived. They ranged from huge stands of mountain longleaf pine that grew amidst an open grassy understory to extensive and dense hardwood forests. The longleaf pine—unique for its dense core used for naval stores, lumber, railroad ties, and “heart-pine” floors—once constituted the most extensive ecosystem in North America (90 million acres); that acreage has now shrunk to less than 3 million. That forest nurtured a now-imperiled ecosystem of 35 species of amphibians, 56 types of reptiles,

Sipsey Wilderness Area Stream

88 varieties of birds, and 40 species of mammals. Alabama conservationists fought an uphill battle to create the Forever Wild Program to purchase and restore endangered habitat and by 2008 had accumulated 667,000 acres of publicly owned land, mainly in the Bankhead, Conecuh, Talladega, and Tuskegee national forests. The most pristine areas, such as the Walls of Jericho at the upper end of Paint Rock Valley and Bee Branch in Bankhead Forest’s Sipsey Wilderness (which contains one 500-year-old tulip poplar that rises 150 feet off the forest floor) can take away the breath of an intrepid hiker not only from the exertion necessary to reach the sights, but for the sheer beauty and grandeur of the landscape.

Sipsey Wilderness Area Stream

88 varieties of birds, and 40 species of mammals. Alabama conservationists fought an uphill battle to create the Forever Wild Program to purchase and restore endangered habitat and by 2008 had accumulated 667,000 acres of publicly owned land, mainly in the Bankhead, Conecuh, Talladega, and Tuskegee national forests. The most pristine areas, such as the Walls of Jericho at the upper end of Paint Rock Valley and Bee Branch in Bankhead Forest’s Sipsey Wilderness (which contains one 500-year-old tulip poplar that rises 150 feet off the forest floor) can take away the breath of an intrepid hiker not only from the exertion necessary to reach the sights, but for the sheer beauty and grandeur of the landscape.

Soils contain similar diversity, ranging northward from the sandy Coastal Plain, up through the thin layer of fertile soils in the Wiregrass, into the counties of the Black Belt (with their mixture of sandy, grey and bluish, loamy prairie soil that turns a dull, grey charcoal or ashy black when wet), to the rocky soils of the Piedmont, and finally to the rich alluvial lands of the Tennessee Valley.

People

Aerial View of Moundville

Human habitation of the Southeast began sometime between 15,000 and 11,500 years ago when the people of the Paleoindian period reached the region after their long trek from Asia. A hunting and gathering society without pottery, substantial houses, or domesticated plants and animals, they left little trace of their existence beyond magnificent Clovis projectile points at their staging areas on the Tennessee River. The Indians of the Archaic period, which followed between 10,500 and 3,000 years ago, bequeathed a much denser collection of tools and weapons. They continued to gather nuts, wild fruits, and berries and hunted bear, bison, deer, and other large animals, but they also lived among larger kinship groups, inhabited bluff shelters, and migrated in seasonal moves from those shelters in winter to encampments along lowland rivers in springtime. The peoples of the subsequent Woodland period developed the technology to replace heavy stone vessels with pottery. Changes of season no longer required changes of habitation. Indians lived in semi-permanent dwellings and settlements, which led to variations in rank, wealth, and status. They cultivated crops, saved seeds, and stabilized their food supply. These patterns continued into the Mississippian period, during which Indians organized into chiefdoms such as the impressive center at Moundville, in Hale County, with its tall Temple Mound, magnificent pottery, and complex agricultural organization. Native American culture also provided the state’s name: French settlers named a cultural group in central Alabama the “Alibamons,” a corruption of a Choctaw word meaning to cut, gather, or trim weeds or plants—hence the generally accepted translation of “Alabama” as “vegetation gatherers.”

Aerial View of Moundville

Human habitation of the Southeast began sometime between 15,000 and 11,500 years ago when the people of the Paleoindian period reached the region after their long trek from Asia. A hunting and gathering society without pottery, substantial houses, or domesticated plants and animals, they left little trace of their existence beyond magnificent Clovis projectile points at their staging areas on the Tennessee River. The Indians of the Archaic period, which followed between 10,500 and 3,000 years ago, bequeathed a much denser collection of tools and weapons. They continued to gather nuts, wild fruits, and berries and hunted bear, bison, deer, and other large animals, but they also lived among larger kinship groups, inhabited bluff shelters, and migrated in seasonal moves from those shelters in winter to encampments along lowland rivers in springtime. The peoples of the subsequent Woodland period developed the technology to replace heavy stone vessels with pottery. Changes of season no longer required changes of habitation. Indians lived in semi-permanent dwellings and settlements, which led to variations in rank, wealth, and status. They cultivated crops, saved seeds, and stabilized their food supply. These patterns continued into the Mississippian period, during which Indians organized into chiefdoms such as the impressive center at Moundville, in Hale County, with its tall Temple Mound, magnificent pottery, and complex agricultural organization. Native American culture also provided the state’s name: French settlers named a cultural group in central Alabama the “Alibamons,” a corruption of a Choctaw word meaning to cut, gather, or trim weeds or plants—hence the generally accepted translation of “Alabama” as “vegetation gatherers.”

The increasing innovation and diversity of Native American life was shattered by the invasion of Europeans in 1540. Spaniard Hernando DeSoto landed in Florida a year earlier, then meandered through Georgia and the Carolinas in search of gold and silver. His explorations brought him into present-day Alabama along the Coosa River in 1540, culminating in the Battle of Mabila on October 18. This attack on a walled town of Chief Tascaluza probably was the bloodiest battle ever fought between Indians and whites on North American soil, with an estimated 2,500 to 3,000 killed. More destructive were the diseases left behind by the Spanish, including measles, mumps, and smallpox, against which Indians had no immunities. The result was a pandemic that killed perhaps three-fourths of the region’s Indian peoples and completely disrupted their way of life. By the time French explorers reached Mobile in 1702, they encountered a Native American culture vastly different from the one encountered by DeSoto and his men.

Fort Toulouse

Permanent European settlement began with a French expedition headed by the Le Moyne brothers—Pierre, known as d’Iberville, and Jean-Baptiste, known as Bienville—who initially founded a small French colony at Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff, up the Mobile River from the present city of Mobile. Flooding in 1711 prompted the French to move their colony down river to the present site of Mobile. This settlement became the capital of French Louisiana from 1711 to 1720, the site of the first Mardi Gras celebration in the future United States, and the first permanent white settlement in Alabama. Exploring upriver from Mobile, the French established Fort Toulouse at the confluence of the Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers in 1717 as the easternmost defense of the new French empire in Alabama.

Fort Toulouse

Permanent European settlement began with a French expedition headed by the Le Moyne brothers—Pierre, known as d’Iberville, and Jean-Baptiste, known as Bienville—who initially founded a small French colony at Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff, up the Mobile River from the present city of Mobile. Flooding in 1711 prompted the French to move their colony down river to the present site of Mobile. This settlement became the capital of French Louisiana from 1711 to 1720, the site of the first Mardi Gras celebration in the future United States, and the first permanent white settlement in Alabama. Exploring upriver from Mobile, the French established Fort Toulouse at the confluence of the Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers in 1717 as the easternmost defense of the new French empire in Alabama.

French, Spanish, British, and American interests collided along the Gulf Coast, precipitating a century of intrigue, maneuvering for advantage among the various Indian nations for control of the lucrative deerskin trade, and spurring increasingly frequent armed confrontations. This intrigue did not end until the Treaty of Fort Jackson in August 1814, falling on the heels of the Creek defeat at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, which forced the Creek Nation to relinquish claims to 14 million acres of land west of the Coosa River. By 1837, the Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Cherokees had lost virtually all of their holdings in the state and the vast majority of the people were relocated to reservations in Oklahoma.

Statehood to the Civil War

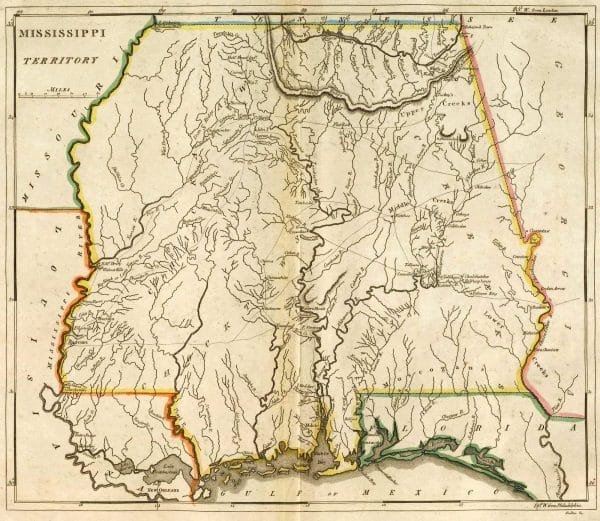

Mississippi Territory

Alabama was originally part of the Mississippi Territory, but when Mississippi entered the Union in 1817, the Alabama counties became a new territory that was itself admitted into the Union two years later on December 14, 1819. Desiring as many slave states as possible in the newly opened Southwest, as the region was then known, southern congressmen forced this division. After Indian removal (and sometimes before) land-hungry settlers poured into Alabama from Virginia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, and even more distant points in a great land rush known as “Alabama Fever.” Some brought large numbers of slaves and great wealth to the fertile new bottom lands. Others brought little more than a family full of children and the clothes on their backs. The wealthy ones waited patiently for federal land surveys and bought the best lands for top dollar. The poor ones “squatted” illegally on the first unoccupied piece of land that appealed to them, then elected politicians who promised to give them first claim to buy the land at the lowest possible price.

Mississippi Territory

Alabama was originally part of the Mississippi Territory, but when Mississippi entered the Union in 1817, the Alabama counties became a new territory that was itself admitted into the Union two years later on December 14, 1819. Desiring as many slave states as possible in the newly opened Southwest, as the region was then known, southern congressmen forced this division. After Indian removal (and sometimes before) land-hungry settlers poured into Alabama from Virginia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, and even more distant points in a great land rush known as “Alabama Fever.” Some brought large numbers of slaves and great wealth to the fertile new bottom lands. Others brought little more than a family full of children and the clothes on their backs. The wealthy ones waited patiently for federal land surveys and bought the best lands for top dollar. The poor ones “squatted” illegally on the first unoccupied piece of land that appealed to them, then elected politicians who promised to give them first claim to buy the land at the lowest possible price.

The squatters’ political hero was Tennessean Andrew Jackson, victor of the battles of Horseshoe Bend and New Orleans, who went on to win the presidency twice and oversee the removal of Alabama’s Native Americans. Jackson’s glorification of the common people, his opposition to centralized banking, and his early advocacy of states’ rights and southern principles endeared him to Alabama’s masses and created the state’s early political divisions between Jacksonian Democrats and Whigs.

Although Alabama’s early political leaders could be found in both camps, wealthier planters, businessmen, and the well-educated gravitated toward the Whig Party, and their geographical center tended to be in towns and on Black Belt plantations. People in the Wiregrass and hill country, in contrast, favored Jackson.

From the first 1819 constitutional convention in Huntsville, Alabamians made it clear that they did not trust authority. They limited the terms of governors and legislators and made it easy to override gubernatorial vetoes. They extended the ballot to any white male more than 21 years of age, without restrictions based on church membership, literacy, or land ownership. As a consequence, Alabama established (along with Mississippi) perhaps the most liberal basis for suffrage found in the early Republic.

Elmore County Church

Egalitarian churches reinforced democratic political assumptions. It was no surprise that Baptists came to dominate the state’s religious landscape. Preeminently a church of the people, the denomination had no hierarchy, preferred ministers who not only preached on Sunday but who also earned their livelihood in ways similar to their congregants, enforced no educational or theological tests, believed that every Christian was his own priest and every church was completely autonomous, and was one with its culture in most respects. Its ministers relied on spell-binding oratory, emotional revivals, and the ultimate authority of personal experience and Holy Scripture to convert others to their ways. And even among Baptists, hyper-Calvinistic Primitive Baptists tended to represent poorer rural people, while Southern Baptists were better educated and more urban.

Elmore County Church

Egalitarian churches reinforced democratic political assumptions. It was no surprise that Baptists came to dominate the state’s religious landscape. Preeminently a church of the people, the denomination had no hierarchy, preferred ministers who not only preached on Sunday but who also earned their livelihood in ways similar to their congregants, enforced no educational or theological tests, believed that every Christian was his own priest and every church was completely autonomous, and was one with its culture in most respects. Its ministers relied on spell-binding oratory, emotional revivals, and the ultimate authority of personal experience and Holy Scripture to convert others to their ways. And even among Baptists, hyper-Calvinistic Primitive Baptists tended to represent poorer rural people, while Southern Baptists were better educated and more urban.

Education was equally democratic. The population was slow to endorse state schools and did not establish the first statewide system until 1854. Always poorly funded, largely through local contributions, legalized gambling, fund raisers, and fees, schools also confronted parents determined to decide what their children learned. Teaching was not a particularly respected profession, and most parents believed functional literacy was quite enough education anyway. Although in time Alabama schools would produce scholars such as E. O. Wilson, arguably the greatest evolutionary biologist of the late twentieth century, many schools performed well below the standards of the Midwest and Northeast. After the Civil War, Alabama colleges actually enrolled more students per capita than similar institutions in other regions, but they possessed far fewer books, raised much smaller endowments, and could afford only basic laboratory equipment and supplies. Not until the advent of federal aid to education in the middle of the twentieth century did Alabama colleges and universities begin to close the gap in facilities.

Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church in Selma

Religion and education reinforced strong class divisions present in early Alabama politics. Primitive Baptists and poorly educated folk especially sided with Andrew Jackson who wanted to abolish the state bank and remove Indians and who rejected state subsidies to fund railroads, canals, and similar internal improvements. They also were often suspicious of public schools and colleges and favored free land. Whigs, Presbyterians, and Episcopalians (who, although small in number, were politically powerful and well-educated) were more likely to favor strong banks, industrialization, educational and mental health reforms, and women’s rights. Whigs argued that governmental action could benefit society and extend democracy. Democrats feared government and saw it as a threat to personal freedom and autonomy.

Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church in Selma

Religion and education reinforced strong class divisions present in early Alabama politics. Primitive Baptists and poorly educated folk especially sided with Andrew Jackson who wanted to abolish the state bank and remove Indians and who rejected state subsidies to fund railroads, canals, and similar internal improvements. They also were often suspicious of public schools and colleges and favored free land. Whigs, Presbyterians, and Episcopalians (who, although small in number, were politically powerful and well-educated) were more likely to favor strong banks, industrialization, educational and mental health reforms, and women’s rights. Whigs argued that governmental action could benefit society and extend democracy. Democrats feared government and saw it as a threat to personal freedom and autonomy.

Despite enslavement, African Americans were not passive victims of a system that denied them the right to education or control of their own churches. They found ways to maintain their dignity, defined the meaning of Christian symbols in new ways (the Biblical story of the Hebrew exodus from Egyptian captivity became a metaphor for their own anticipated emancipation from slavery in the South), developed their own style of preaching and singing that whites often criticized, and used Christianity to meet their own personal and community needs.

Slavery, States’ Rights, and Secession

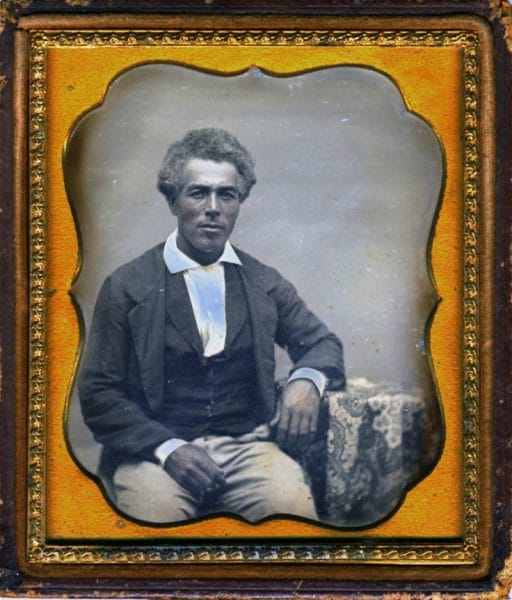

Horace King

By the mid-nineteenth century, such debates were swept aside by questions about slavery, states’ rights, and secession. French settlers of Mobile had introduced slavery early in the 1700s. Pioneers who entered the Tennessee Valley a century later brought many slaves with them. Alabama Fever introduced an expansion of slavery. Increases in gang labor on cotton plantations over the ensuing four decades drove the ratio of slaves to whites ever higher: in 1820, 85,500 whites (67 percent of the population) compared with 42,500 slaves (33 percent); by 1840, 335,000 whites (57 percent) to 255,500 slaves (43 percent); and by 1860, 526,000 whites (55 percent) to 438,000 slaves (45 percent). Between 1830 and 1860, Alabama’s white population increased by 171 percent and its black enslaved population by 270 percent. Only a few thousand were free blacks, such as the master bridge builder Horace King; the vast majority were slaves who worked in various phases of the developing plantation system. Slavery was concentrated in the Tennessee Valley and the Black Belt, the heart of cotton culture in the state. The industrial revolution in Britain generated a cotton textile industry that consumed huge quantities of raw cotton. In 1820, Alabama produced a bit less than 4 percent of U.S. cotton; by 1849 the state led all other states, producing 23 percent. And cotton constituted half of all U.S. exports. The port of Mobile, the endpoint of river transport for all cotton lands south of the mountains, became America’s third busiest port. New Orleans, which among other regions served the cotton fields of the Tennessee Valley, ranked behind only the port of New York in traffic.

Horace King

By the mid-nineteenth century, such debates were swept aside by questions about slavery, states’ rights, and secession. French settlers of Mobile had introduced slavery early in the 1700s. Pioneers who entered the Tennessee Valley a century later brought many slaves with them. Alabama Fever introduced an expansion of slavery. Increases in gang labor on cotton plantations over the ensuing four decades drove the ratio of slaves to whites ever higher: in 1820, 85,500 whites (67 percent of the population) compared with 42,500 slaves (33 percent); by 1840, 335,000 whites (57 percent) to 255,500 slaves (43 percent); and by 1860, 526,000 whites (55 percent) to 438,000 slaves (45 percent). Between 1830 and 1860, Alabama’s white population increased by 171 percent and its black enslaved population by 270 percent. Only a few thousand were free blacks, such as the master bridge builder Horace King; the vast majority were slaves who worked in various phases of the developing plantation system. Slavery was concentrated in the Tennessee Valley and the Black Belt, the heart of cotton culture in the state. The industrial revolution in Britain generated a cotton textile industry that consumed huge quantities of raw cotton. In 1820, Alabama produced a bit less than 4 percent of U.S. cotton; by 1849 the state led all other states, producing 23 percent. And cotton constituted half of all U.S. exports. The port of Mobile, the endpoint of river transport for all cotton lands south of the mountains, became America’s third busiest port. New Orleans, which among other regions served the cotton fields of the Tennessee Valley, ranked behind only the port of New York in traffic.

Most of Alabama’s wealth was invested in land and slaves. A few industrialists, such as textile magnate and cotton-gin manufacturer Daniel Pratt, prospered in Alabama, but a Jeffersonian preference for rural life and agricultural pursuits slowed development of Alabama’s mineral wealth until the Civil War.

As debates about the expansion of slavery into new territories, states’ rights, and the morality of slavery proliferated, arguments between Alabama Unionists and secessionists became more passionate. Despite Alabama legislator William Lowndes Yancey’s national leadership of Confederate supporters, his party had a tough sell in the state. All through the 1840s and 1850s, forceful Alabama politicians, journalists, and orators opposed secession. But in time those who favored withdrawal from the Union gained the upper hand. Their cause was simpler than that of the Unionists, who were divided between those who rejected secession for any reason and those who simply preferred to wait to see what other southern states did before deciding. In January 1861, an elected state convention resolved the issue by a relatively close vote of 61 to 39 in favor of leaving the Union.

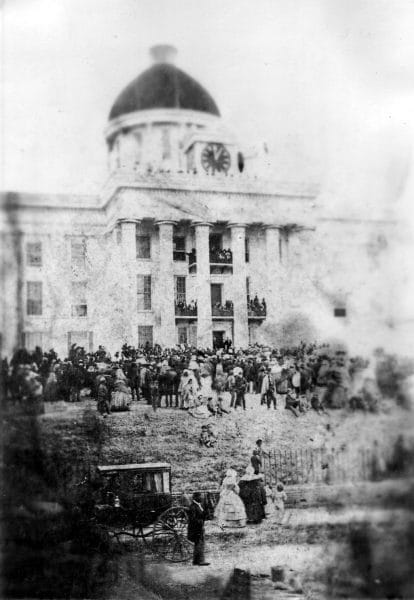

Inauguration of Jefferson Davis

Formation of the Confederacy and the outbreak of war solidified sentiment in Alabama. Wartime enthusiasm, the fervor of friends and neighbors, and location of the initial Confederate capital in Montgomery all brought many Unionists into the Confederate fold. So did Northern armies invading southern states. Although Alabama did not rival Virginia, Tennessee, or Georgia as a theater of war, it did serve as the breadbasket and arsenal of the new Confederate States of America. Outside of the occupied Tennessee Valley, federal presence was generally limited to raids, so Alabama farmers and herdsmen were free to furnish large quantities of corn, pork, and beef to Confederate armies. As the needs of war demanded, the state finally mobilized its iron resources and furnaces to build cannons, swords, muskets, rails, plating for armored ships, as well as shot and shell.

Inauguration of Jefferson Davis

Formation of the Confederacy and the outbreak of war solidified sentiment in Alabama. Wartime enthusiasm, the fervor of friends and neighbors, and location of the initial Confederate capital in Montgomery all brought many Unionists into the Confederate fold. So did Northern armies invading southern states. Although Alabama did not rival Virginia, Tennessee, or Georgia as a theater of war, it did serve as the breadbasket and arsenal of the new Confederate States of America. Outside of the occupied Tennessee Valley, federal presence was generally limited to raids, so Alabama farmers and herdsmen were free to furnish large quantities of corn, pork, and beef to Confederate armies. As the needs of war demanded, the state finally mobilized its iron resources and furnaces to build cannons, swords, muskets, rails, plating for armored ships, as well as shot and shell.

Slightly fewer than 100,000 Alabama men served in Confederate military service, although a tenth of those deserted, mainly after the July 1863 defeats and the expanding drought, famine, and hunger of the later war years. Sentiment for peace increased as well, and several thousand white Alabamians joined some 5,000 African Americans in the Union Army.

Reconstruction and Beyond

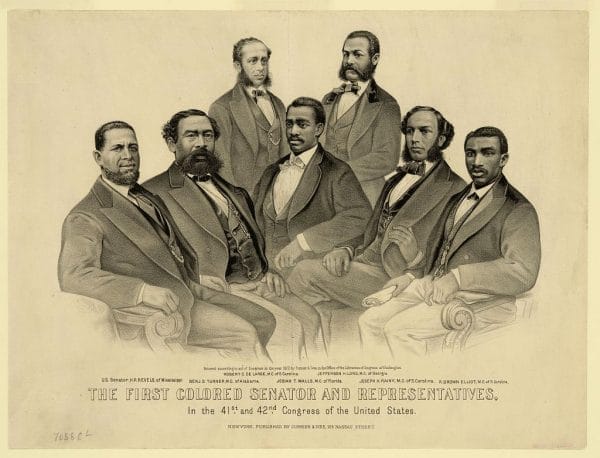

Black Legislators Elected During Reconstruction

After the war ended and Reconstruction came to the South, ideological and partisan divisions widened. Prewar Unionists, especially in north Alabama, gravitated toward the Union League and the Republican Party, as did newly emancipated blacks throughout the state. Many prominent Unionist planters were elected to Congress and the state legislature as Republicans (called “scalawags” by their Democratic opponents). A smaller number of northern white opportunists and idealists (called “carpetbaggers”) also assumed leadership of the Republican Party. Republicans elected many African Americans to office as well. With many former Confederates disfranchised by congressional action, Republicans performed well in most elections between 1866 and 1876 and elected many local officials on into the 1880s. But whereas Democrats united against Republican rule and black participation, Republicans divided over black participation in their party, with the majority scalawag wing of the party highly dubious about their African American colleagues. This division allowed the newly renamed Conservative Democratic Party to regain the governor’s office in 1874, write a new conservative constitution the following year, and methodically drive Republicans from office at every level.

Black Legislators Elected During Reconstruction

After the war ended and Reconstruction came to the South, ideological and partisan divisions widened. Prewar Unionists, especially in north Alabama, gravitated toward the Union League and the Republican Party, as did newly emancipated blacks throughout the state. Many prominent Unionist planters were elected to Congress and the state legislature as Republicans (called “scalawags” by their Democratic opponents). A smaller number of northern white opportunists and idealists (called “carpetbaggers”) also assumed leadership of the Republican Party. Republicans elected many African Americans to office as well. With many former Confederates disfranchised by congressional action, Republicans performed well in most elections between 1866 and 1876 and elected many local officials on into the 1880s. But whereas Democrats united against Republican rule and black participation, Republicans divided over black participation in their party, with the majority scalawag wing of the party highly dubious about their African American colleagues. This division allowed the newly renamed Conservative Democratic Party to regain the governor’s office in 1874, write a new conservative constitution the following year, and methodically drive Republicans from office at every level.

African Americans slowly turned from political to social reconstruction, withdrawing from white churches to the work of building their own families and institutions. Although most had no economic resources and drifted into tenancy or low-skill industrial jobs, a few acquired land, established businesses, or entered professions.

Sloss Blast Furnaces

Rapid industrialization after 1880 opened new opportunities to both poor blacks and whites. Alabama possessed only 1,800 miles of railroad track in 1880, compared with 5,200 by 1910. Birmingham, which was not incorporated as a town until 1871, recruited capital and labor from across America and Europe for its iron, steel, and textile mills and its coal and iron ore mines. It reached a population of more than 100,000 early in the new century, making it the South’s third most populous city. Statewide, coal and iron ore mining, textile, iron and steel manufacturing, railroad building, and timber and turpentine work vied with farming for economic supremacy. Cotton production remained dominant in agriculture, however, even as prices for the commodity plummeted.

Sloss Blast Furnaces

Rapid industrialization after 1880 opened new opportunities to both poor blacks and whites. Alabama possessed only 1,800 miles of railroad track in 1880, compared with 5,200 by 1910. Birmingham, which was not incorporated as a town until 1871, recruited capital and labor from across America and Europe for its iron, steel, and textile mills and its coal and iron ore mines. It reached a population of more than 100,000 early in the new century, making it the South’s third most populous city. Statewide, coal and iron ore mining, textile, iron and steel manufacturing, railroad building, and timber and turpentine work vied with farming for economic supremacy. Cotton production remained dominant in agriculture, however, even as prices for the commodity plummeted.

Declining quality of life for farmers and wretched conditions in many new industries alienated the poor, both black and white, and drove them into new agrarian-labor alliances such as the Knights of Labor, the United Mine Workers, the Farmers’ Alliance, and finally during the depression of 1890s, the Jeffersonian Democratic (Populist) Party. Many Republicans joined this protest movement, and in 1892 and 1894 Conservative Democrats had to steal black votes in the Black Belt to prevent a Populist victory.

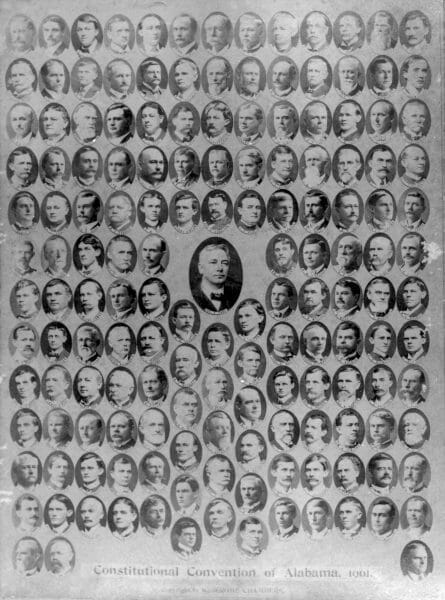

1901 Constitutional Convention

Political corruption became so widespread at this time that demands for reform arose from all sectors of the population. Ironically, this “reform” consisted of the 1901 Constitution, which sought to “cleanse” politics by disfranchising virtually all black voters and many poor whites as well. A constitutional convention consisting only of white males who were nearly all Democrats, and mostly lawyers and businessmen, also transferred decision-making from the 67 individual counties to the state capitol in Montgomery, limited property taxes, and effectively installed political power in large landowners and their Birmingham-area business allies. Planters eager to guarantee ample supplies of unskilled black tenants and sharecroppers, and industrialists equally determined to recruit low-skill, low-wage workers, had no incentive to improve public schools, public health, or public institutions and together harnessed the state to a nineteenth-century racist document rooted in the economic realities of an agrarian, backward economy. Tragically, more than a century later, when all those realities have changed, the same document still governs Alabama, strangling modernization and reform until even many of the interests that had applauded the original document now beg its citizens to write a new one.

1901 Constitutional Convention

Political corruption became so widespread at this time that demands for reform arose from all sectors of the population. Ironically, this “reform” consisted of the 1901 Constitution, which sought to “cleanse” politics by disfranchising virtually all black voters and many poor whites as well. A constitutional convention consisting only of white males who were nearly all Democrats, and mostly lawyers and businessmen, also transferred decision-making from the 67 individual counties to the state capitol in Montgomery, limited property taxes, and effectively installed political power in large landowners and their Birmingham-area business allies. Planters eager to guarantee ample supplies of unskilled black tenants and sharecroppers, and industrialists equally determined to recruit low-skill, low-wage workers, had no incentive to improve public schools, public health, or public institutions and together harnessed the state to a nineteenth-century racist document rooted in the economic realities of an agrarian, backward economy. Tragically, more than a century later, when all those realities have changed, the same document still governs Alabama, strangling modernization and reform until even many of the interests that had applauded the original document now beg its citizens to write a new one.

Helen Keller, 1925

With African Americans removed from politics and race no longer the compelling issue of public discourse, whites divided along lines of class, profession, and economic status. Many working-class whites joined unions. Many ministers, teachers, social workers, women (notable among them the remarkable Helen Keller, who became the worldwide spokesperson for the physically challenged), professionals, and even politicians began to agitate for myriad reforms: opposition to child labor, the convict-lease system, prostitution, the sale of alcoholic beverages. They also called for better educational and mental health facilities, public health, and woman suffrage. Conservative Democrats mobilized to defeat such reforms, prevailing in most of the battles but losing some. The contours of this conservative reform class division prevailed until the 1950s and 1960s, when race once again came to dominate Alabama’s political discourse. Governors Braxton Bragg Comer, Thomas Kilby, Bibb Graves, and James E. Folsom Sr. represented various elements of reform, while others largely fought to preserve the 1901 status quo. Reformers gained allies mainly among the north Alabama congressional delegation as well as U.S. senators John Bankhead Jr., Lister Hill, Hugo Black, and John Sparkman.

Helen Keller, 1925

With African Americans removed from politics and race no longer the compelling issue of public discourse, whites divided along lines of class, profession, and economic status. Many working-class whites joined unions. Many ministers, teachers, social workers, women (notable among them the remarkable Helen Keller, who became the worldwide spokesperson for the physically challenged), professionals, and even politicians began to agitate for myriad reforms: opposition to child labor, the convict-lease system, prostitution, the sale of alcoholic beverages. They also called for better educational and mental health facilities, public health, and woman suffrage. Conservative Democrats mobilized to defeat such reforms, prevailing in most of the battles but losing some. The contours of this conservative reform class division prevailed until the 1950s and 1960s, when race once again came to dominate Alabama’s political discourse. Governors Braxton Bragg Comer, Thomas Kilby, Bibb Graves, and James E. Folsom Sr. represented various elements of reform, while others largely fought to preserve the 1901 status quo. Reformers gained allies mainly among the north Alabama congressional delegation as well as U.S. senators John Bankhead Jr., Lister Hill, Hugo Black, and John Sparkman.

Civil Rights

The 1962 election of George C. Wallace as governor dramatically changed the state’s politics. A populist ally of Folsom earlier in his career, Wallace united working and middle-class whites around rejection of the civil rights movement and federally mandated racial integration.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

A number of local black leaders, including Selma’s J. L. Chestnut Jr.; Montgomery’s E. D. Nixon, Rosa Parks, and Fred D. Gray; Tuskegee professor Charles Gomillion; Birmingham’s Fred Shuttlesworth; and Mobile postman John L. LeFlore had long agitated for racial justice. But it was not until the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott that the implications of the previous year’s Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case fully dawned on whites. Massive resistance by African Americans to segregation soon triggered a counter-movement of massive resistance by whites to federal court orders. States’ rights doctrines of interposition (sovereign governors interposing themselves between their citizens and federal authorities) matched black doctrines of civil disobedience (the moral obligation to peacefully disobey unjust laws).

Montgomery Bus Boycott

A number of local black leaders, including Selma’s J. L. Chestnut Jr.; Montgomery’s E. D. Nixon, Rosa Parks, and Fred D. Gray; Tuskegee professor Charles Gomillion; Birmingham’s Fred Shuttlesworth; and Mobile postman John L. LeFlore had long agitated for racial justice. But it was not until the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott that the implications of the previous year’s Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case fully dawned on whites. Massive resistance by African Americans to segregation soon triggered a counter-movement of massive resistance by whites to federal court orders. States’ rights doctrines of interposition (sovereign governors interposing themselves between their citizens and federal authorities) matched black doctrines of civil disobedience (the moral obligation to peacefully disobey unjust laws).

Alabama officials could dispute racial inequality but had trouble convincing even themselves (much less federal judges such as Winston County Republican Frank M. Johnson Jr.) that the state provided equal opportunities to African Americans. A report by the state school superintendent in 1908 had noted that African Americans constituted 44 percent of the state’s school population but received only 12 percent of the state’s educational funding. In 1960, Lowndes and Wilcox counties, with a total of 11,200 adult African Americans, had not a single registered black voter. Although the two counties together contained only 4,600 white adults, they somehow managed to register 5,300 white voters, or enough to firmly control local politics.

Gov. Wallace’s Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

The 1964 federal Public Accommodations Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 both owed their passage largely to the racial excesses of white Alabama officials, particularly Birmingham’s police commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, Mayor Art Hanes, Selma’s sheriff Jim Clark, and especially Governor Wallace. Nonetheless, acts that made Wallace a pariah worldwide did not sully his reputation among many American voters, as he proved in his presidential bids outside the South in 1968 and 1972. Within his home state, Wallace became the very embodiment of the state’s defiant motto, “We Dare Defend Our Rights.” Counting the abbreviated term that his wife, Lurleen, served before he was able to amend the constitution to allow governors to hold two consecutive terms, Wallace held the governor’s office for an unprecedented 18 years. As more and more blacks voted, however, white politicians moderated their racism. And by the 1980s, Alabama and Mississippi led the nation in the number of black elected officials. By the 1990s, Alabama’s population was 25 percent black and its legislators also were 25 percent black, a figure few other states could claim.

Gov. Wallace’s Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

The 1964 federal Public Accommodations Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 both owed their passage largely to the racial excesses of white Alabama officials, particularly Birmingham’s police commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, Mayor Art Hanes, Selma’s sheriff Jim Clark, and especially Governor Wallace. Nonetheless, acts that made Wallace a pariah worldwide did not sully his reputation among many American voters, as he proved in his presidential bids outside the South in 1968 and 1972. Within his home state, Wallace became the very embodiment of the state’s defiant motto, “We Dare Defend Our Rights.” Counting the abbreviated term that his wife, Lurleen, served before he was able to amend the constitution to allow governors to hold two consecutive terms, Wallace held the governor’s office for an unprecedented 18 years. As more and more blacks voted, however, white politicians moderated their racism. And by the 1980s, Alabama and Mississippi led the nation in the number of black elected officials. By the 1990s, Alabama’s population was 25 percent black and its legislators also were 25 percent black, a figure few other states could claim.

Alabama Comes Back

Saturn V

During the early Wallace era, the state languished as the presidential hopeful traveled the nation propounding his segregationist views to nationwide audiences of like-minded whites. Birmingham, which in 1950 had only 14,000 people less than Atlanta and which led the South in the number of industrial establishments employing more than 100 workers as well as in total number of production workers, went into steep decline. The paralysis of racial conflict, the battering by the international media, the loss of 25,000 steel-related jobs between 1950 and 1970, the mechanization of coal mining with its attendant loss of thousands of jobs, all conspired to leave the city crippled and dispirited. To make matters worse, Birmingham’s tiny neighbor to the north, Huntsville, had eschewed racial conflict, promoted engineering, the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, and what came to be called the “high-tech sector,” and thrived.

Saturn V

During the early Wallace era, the state languished as the presidential hopeful traveled the nation propounding his segregationist views to nationwide audiences of like-minded whites. Birmingham, which in 1950 had only 14,000 people less than Atlanta and which led the South in the number of industrial establishments employing more than 100 workers as well as in total number of production workers, went into steep decline. The paralysis of racial conflict, the battering by the international media, the loss of 25,000 steel-related jobs between 1950 and 1970, the mechanization of coal mining with its attendant loss of thousands of jobs, all conspired to leave the city crippled and dispirited. To make matters worse, Birmingham’s tiny neighbor to the north, Huntsville, had eschewed racial conflict, promoted engineering, the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, and what came to be called the “high-tech sector,” and thrived.

UAB’s Heritage Hall

In the 1970s and 1980s, Birmingham entrusted its future to a number of reform mayors, including its first black mayor, Richard Arrington; diversified its economy; mobilized the talents of a new generation of progressive businessmen; and began a slow but steady recovery. The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) became home to a world-class medical school; insurance and banking businesses thrived (at one time Birmingham contained the headquarters of four of the nation’s top 50 banks on opposite corners of one intersection); some of the nation’s premier engineering construction firms developed locally; and health care replaced steel-making as the city’s economic engine. It also gained a reputation as a food mecca, with Alabama-born top chefs like Frank Stitt returning to open innovative restaurants in the city.

UAB’s Heritage Hall

In the 1970s and 1980s, Birmingham entrusted its future to a number of reform mayors, including its first black mayor, Richard Arrington; diversified its economy; mobilized the talents of a new generation of progressive businessmen; and began a slow but steady recovery. The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) became home to a world-class medical school; insurance and banking businesses thrived (at one time Birmingham contained the headquarters of four of the nation’s top 50 banks on opposite corners of one intersection); some of the nation’s premier engineering construction firms developed locally; and health care replaced steel-making as the city’s economic engine. It also gained a reputation as a food mecca, with Alabama-born top chefs like Frank Stitt returning to open innovative restaurants in the city.

Mercedes-Benz Production Line

Similar stories occurred statewide, especially after 1992, when Mercedes-Benz located its first North American plant in Vance, between Birmingham and Tuscaloosa. Honda, Hyundai, and Toyota plants followed, together with a Kia plant in Georgia just across the Chattahoochee River from Valley, Alabama. Automotive parts plants quickly replaced declining textile mills, albeit with far fewer jobs, but with better pay. David G. Bronner, CEO of the Retirement Systems of Alabama, used his agency’s resources to revamp the Montgomery and Mobile skylines and construct the award-winning Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail.

Mercedes-Benz Production Line

Similar stories occurred statewide, especially after 1992, when Mercedes-Benz located its first North American plant in Vance, between Birmingham and Tuscaloosa. Honda, Hyundai, and Toyota plants followed, together with a Kia plant in Georgia just across the Chattahoochee River from Valley, Alabama. Automotive parts plants quickly replaced declining textile mills, albeit with far fewer jobs, but with better pay. David G. Bronner, CEO of the Retirement Systems of Alabama, used his agency’s resources to revamp the Montgomery and Mobile skylines and construct the award-winning Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail.

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, Alabama was generating more jobs than most other states, despite the continuing loss of manufacturing jobs. Total state exports in 2005 exceeded $10 billion for the first time and rose even higher in 2006, mainly because of sales to Canada, Germany, Mexico, Japan, and China. Although the state did not catch industry-leader Michigan, total auto production in Alabama neared one million units a year by 2007.

Baldwin County Cotton Farm

Much of this industrial and business progress came at the expense of agriculture. Although the 1950 federal census was the first to record that most Alabamians no longer farmed for a living, agriculture had been in decline for decades. In 1914, the state’s farmers planted four million acres in cotton alone. Early in the twenty-first century, they devoted only 1.3 million acres to all agricultural crops combined. In 1960, the state boasted 116,000 farms; by 2005, it had only 43,500. In 1940, 1,340,000 Alabamians lived on farms; by 2005, they numbered barely 75,000. Nonetheless, those farms and farmers generated $3.3 billion worth of commodities, mainly in timber, pulpwood, poultry, eggs, cattle, calves, and greenhouse products, which accounted for 84 percent of the total; cotton accounted for only 4 percent. Much of this decline began when the boll weevil reached Alabama in 1910 and during the following decade devastated cotton crops. Despite the efforts of professionals such as Thomas Monroe Campbell and George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute and their fellow research and extension specialists at the land grant universities at Auburn and Alabama A&M University, researchers did not learn how to eradicate the pest until the 1990s.

Baldwin County Cotton Farm

Much of this industrial and business progress came at the expense of agriculture. Although the 1950 federal census was the first to record that most Alabamians no longer farmed for a living, agriculture had been in decline for decades. In 1914, the state’s farmers planted four million acres in cotton alone. Early in the twenty-first century, they devoted only 1.3 million acres to all agricultural crops combined. In 1960, the state boasted 116,000 farms; by 2005, it had only 43,500. In 1940, 1,340,000 Alabamians lived on farms; by 2005, they numbered barely 75,000. Nonetheless, those farms and farmers generated $3.3 billion worth of commodities, mainly in timber, pulpwood, poultry, eggs, cattle, calves, and greenhouse products, which accounted for 84 percent of the total; cotton accounted for only 4 percent. Much of this decline began when the boll weevil reached Alabama in 1910 and during the following decade devastated cotton crops. Despite the efforts of professionals such as Thomas Monroe Campbell and George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute and their fellow research and extension specialists at the land grant universities at Auburn and Alabama A&M University, researchers did not learn how to eradicate the pest until the 1990s.

The boll weevil did speed agricultural diversification. Farmers replaced lost income by planting peanuts, citrus, and soybeans and by raising cattle, hogs, and poultry. Catfish farming in the Black Belt became a half-billion dollar aquaculture by 2007. By the early twenty-first century, small specialized producers were experimenting with organic production of crops for local urban markets in an attempt to survive changing conditions.

Modernization also affected religion. Once the domain primarily of Baptists and Methodists, the state’s religious landscape became much more diverse in the early twentieth century. Catholics became a significant part of European immigration to the Birmingham industrial district, as did smaller numbers of Jews and Orthodox Christians from Greece and Eastern Europe. Pentecostals and Holiness churches established beachheads in the 1890s and became numerous as the twentieth century unfolded. By the twenty-first century, the university and medical complex at UAB attracted Muslims, Buddhists, and those from other religions. Independent megachurches appealed especially to upwardly mobile young suburbanites.

Phenomenal individuals such as Mother Angelica (Rita Antoinette Rizzo) appeared on the state’s religious stage. Attracted to Alabama on behalf of blacks and the poor by the civil rights movement, Mother Angelica established a ministry in Irondale, a Birmingham suburb, in 1957. She began to speak, record lectures and videos, and in 1981 established her own television station, the Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN). She served as CEO of the new network as well as chief lecturer. By 2008, her station was broadcasting 24 hours a day, seven days a week, in 147 countries and territories and, with her AM/FM radio station, reaching an estimated 100 million homes worldwide.

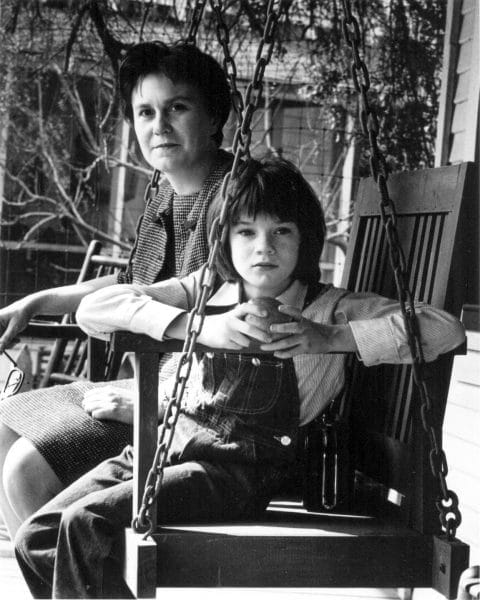

Harper Lee and Mary Badham

A state deemed culturally backward by some also produced literature of high quality. Novelists T. S. Stribling, Shirley Ann Grau, and Harper Lee won Pulitzer Prizes for their novels. Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird became arguably the most beloved American novel of the twentieth century and was read by three out of four American high school students. Inducted into the American Academy of Letters and recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Monroeville native became the premier literary spokesperson for tolerance and judicial fair play for minorities worldwide. Alabama shaped the literary work of many noted African Americans, including Margaret Walker, Zora Neale Hurston, Albert Murray, and Ralph Ellison, who all gained fame elsewhere but were either born in the state, attended college at Tuskegee, or based their novels and stories on Alabama events and settings. Truman Capote, Harper Lee’s next-door neighbor during summers in Monroeville, altered American literature with his quasi-fictional In Cold Blood.

Harper Lee and Mary Badham

A state deemed culturally backward by some also produced literature of high quality. Novelists T. S. Stribling, Shirley Ann Grau, and Harper Lee won Pulitzer Prizes for their novels. Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird became arguably the most beloved American novel of the twentieth century and was read by three out of four American high school students. Inducted into the American Academy of Letters and recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Monroeville native became the premier literary spokesperson for tolerance and judicial fair play for minorities worldwide. Alabama shaped the literary work of many noted African Americans, including Margaret Walker, Zora Neale Hurston, Albert Murray, and Ralph Ellison, who all gained fame elsewhere but were either born in the state, attended college at Tuskegee, or based their novels and stories on Alabama events and settings. Truman Capote, Harper Lee’s next-door neighbor during summers in Monroeville, altered American literature with his quasi-fictional In Cold Blood.

Zora Neale Hurston, 1938

Novelist William March of Mobile authored what some critics claim is the finest American anti-war novel, Company K. Marine Corps infantryman Eugene Sledge wrote a memoir that many historians contend is the finest enlisted man’s account of World War II ever written. His story of war in the South Pacific (With the Old Breed at Pelelieu and Okinawa) captured the horror of war for the 300,000 Alabama men and women who served in the Second World War (in which 6,000 gave their lives and 12 won Congressional Medals of Honor). Renowned for their southern nationalism during the middle of the nineteenth century, they were equally famous for their American patriotism a century later.

Zora Neale Hurston, 1938

Novelist William March of Mobile authored what some critics claim is the finest American anti-war novel, Company K. Marine Corps infantryman Eugene Sledge wrote a memoir that many historians contend is the finest enlisted man’s account of World War II ever written. His story of war in the South Pacific (With the Old Breed at Pelelieu and Okinawa) captured the horror of war for the 300,000 Alabama men and women who served in the Second World War (in which 6,000 gave their lives and 12 won Congressional Medals of Honor). Renowned for their southern nationalism during the middle of the nineteenth century, they were equally famous for their American patriotism a century later.

The arts also thrived during the past century. Establishment of the Alabama Shakespeare Festival (ASF) in Anniston during the early 1970s began a professional repertory company that thrived after moving to Montgomery during the following decade. Philanthropist Winton “Red” Blount invested $22 million in a state-of-the-art facility for the ASF, which became the only full-time professional classical repertory theater in the Southeast, with 400 performances a year that attract 300,000 patrons. ASF also sponsored the Southern Writers’ Project, which continues to commission and premier original plays.

Music flourished as well, particularly folk traditions. In the north Alabama mountains Appalachian ballads, sacred harp/shape note music, white gospel, and spirited fiddle songs predominated. In the Black Belt, African American spirituals, black gospel, blues, jazz, ragtime, and rhythm and blues thrived. The Delmore and Louvin brothers, Hank Williams, Nat “King” Cole, W. C. Handy, James Reese Europe, Erskine Hawkins, Avery Parrish, Lionel Richie, Toni Tennille, Randy Owen, Teddy Gentry, Jim Nabors, and Emmylou Harris provided a musical legacy as diverse as Alabama’s flora and fauna.

Gee’s Bend Quilters

Folk art is equally well represented. From the Gee’s Bend quilters to self-taught artists such as Howard Finster, Bill Traylor, Mose Tolliver (Mose T), Jimmy Lee Sudduth, Charlie Lucas, Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley, Bernice Sims, and Myrtice West, folk artists gained a respected place among American museums and art collectors. Howard Finster, perhaps the most celebrated of the folk artists, was one of 14 siblings born in DeKalb County, the son of a poor sawmill lumberjack. As a boy he experienced religious visions and became a Baptist preacher. After moving just across the state line into northwestern Georgia, he created Paradise Gardens, a sculpture garden using salvaged objects. Rooted in evangelical Christian theology, his visionary art was shown at the Library of Congress, Smithsonian Institute, and Atlanta’s High Museum, and he was featured in Southern Living, Time, Life, and the New York Times. Both presidents Reagan and Clinton hosted Finster in the White House.

Gee’s Bend Quilters

Folk art is equally well represented. From the Gee’s Bend quilters to self-taught artists such as Howard Finster, Bill Traylor, Mose Tolliver (Mose T), Jimmy Lee Sudduth, Charlie Lucas, Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley, Bernice Sims, and Myrtice West, folk artists gained a respected place among American museums and art collectors. Howard Finster, perhaps the most celebrated of the folk artists, was one of 14 siblings born in DeKalb County, the son of a poor sawmill lumberjack. As a boy he experienced religious visions and became a Baptist preacher. After moving just across the state line into northwestern Georgia, he created Paradise Gardens, a sculpture garden using salvaged objects. Rooted in evangelical Christian theology, his visionary art was shown at the Library of Congress, Smithsonian Institute, and Atlanta’s High Museum, and he was featured in Southern Living, Time, Life, and the New York Times. Both presidents Reagan and Clinton hosted Finster in the White House.

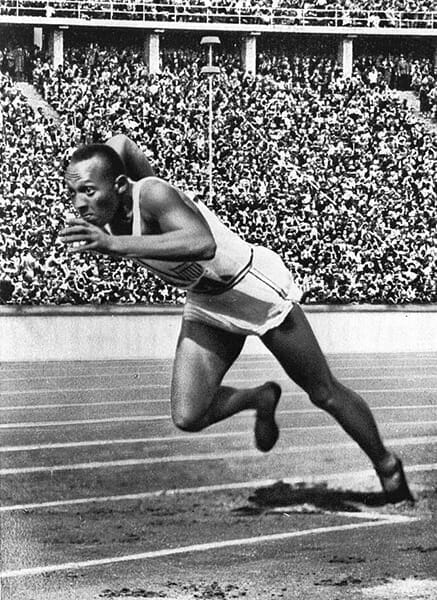

Jesse Owens at the 1936 Olympics

A population that lived so close to nature also celebrated physical exertion. Hunting, fishing, horse racing, and organized sport held a high priority. Perhaps no state has surpassed Alabama in the sports of boxing and track. Even Gov. George C. Wallace was a Golden Gloves boxing champion. Joe Louis Barrow (he eventually dropped his last name) was born in a sharecropper’s cabin near LaFayette. After his family moved to Detroit, he took up boxing. He won and retained the world heavyweight championship for an amazing 13 years. Jesse Owens was also a sharecropper’s son who moved north with his family. In May 1935, running for Ohio State University, he set three world track records and tied another, all in the space of less than an hour in what some sports historians call the greatest single performance in the history of track and field. He went on to win four gold medals at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, a feat unmatched until fellow native Alabamian Carl Lewis equaled that record in the 1984 Olympics.

Jesse Owens at the 1936 Olympics

A population that lived so close to nature also celebrated physical exertion. Hunting, fishing, horse racing, and organized sport held a high priority. Perhaps no state has surpassed Alabama in the sports of boxing and track. Even Gov. George C. Wallace was a Golden Gloves boxing champion. Joe Louis Barrow (he eventually dropped his last name) was born in a sharecropper’s cabin near LaFayette. After his family moved to Detroit, he took up boxing. He won and retained the world heavyweight championship for an amazing 13 years. Jesse Owens was also a sharecropper’s son who moved north with his family. In May 1935, running for Ohio State University, he set three world track records and tied another, all in the space of less than an hour in what some sports historians call the greatest single performance in the history of track and field. He went on to win four gold medals at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, a feat unmatched until fellow native Alabamian Carl Lewis equaled that record in the 1984 Olympics.

End-of-the-century polls of the greatest baseball players of the twentieth century ranked Willie Mays of Birmingham and Hank Aaron of Mobile in the top ten. Sporting News selected Mays as the second best baseball player of the century, and Aaron held the major league record for most home runs. They tied one other player for most appearances in annual all-star games (24 each).

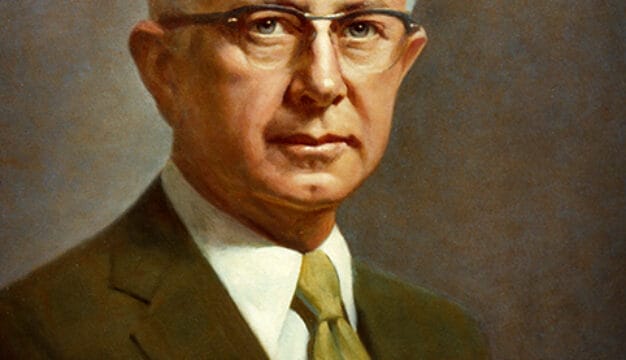

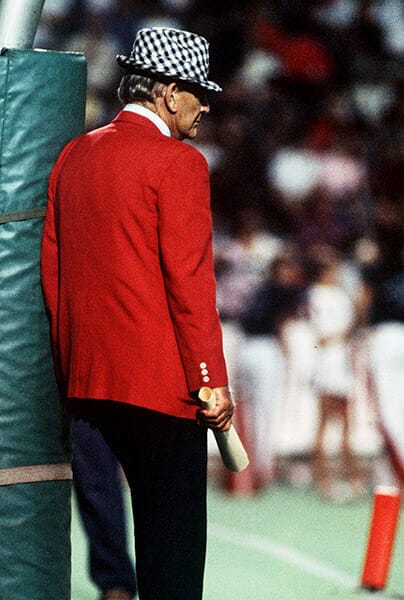

Paul “Bear” Bryant

Similar polls named Paul “Bear” Bryant as the greatest college football coach of the century. As coach of his alma mater, the University of Alabama, he won six national championships to go with the one he won while a player at the Capstone. He also coached the Crimson Tide to 24 bowl games, 14 conference titles, and three undefeated seasons, and was three times voted national coach of the year. Together, Alabama won 12 national championships in 75 years and set national records both for bowl appearances and victories. Bryant ended the century as the winningest major college football coach in history, although another Alabamian and Howard College (now Samford University) player and coach, Bobby Bowden, broke Bryant’s record early in the new century.

Paul “Bear” Bryant

Similar polls named Paul “Bear” Bryant as the greatest college football coach of the century. As coach of his alma mater, the University of Alabama, he won six national championships to go with the one he won while a player at the Capstone. He also coached the Crimson Tide to 24 bowl games, 14 conference titles, and three undefeated seasons, and was three times voted national coach of the year. Together, Alabama won 12 national championships in 75 years and set national records both for bowl appearances and victories. Bryant ended the century as the winningest major college football coach in history, although another Alabamian and Howard College (now Samford University) player and coach, Bobby Bowden, broke Bryant’s record early in the new century.

Of course every state can boast exemplary individual accomplishments in a variety of undertakings. But in Alabama the odds were often stacked against such accomplishment by restrictions of race or class, lack of education, or lack of opportunity. As these barriers diminished and better schools and fairer treatment emancipated the full potential of a hard-working and often over-achieving population, such excellence spread to an ever expanding variety of endeavors.

Further Reading

- Flynt, Wayne. Alabama in the Twentieth Century. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Hamilton, Virginia Van der Veer. Alabama: A History. New York: W. W. Norton, 1977.

- Rogers, William W., et al. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.