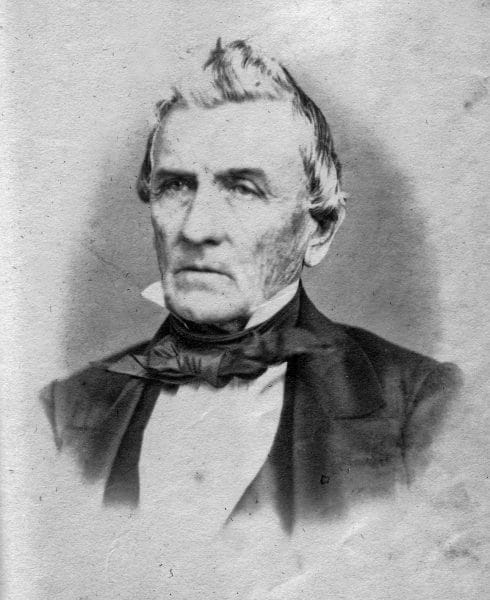

Clement Comer Clay (1835-37)

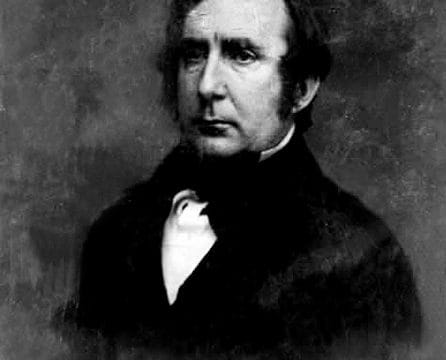

Clement Comer Clay, 1835

Beginning his political career in Alabama as a leading member of the influential Broad River political machine, Clement Comer Clay (1789–1866) ultimately found favor with the voters of the state as a Jacksonian Democrat. His life and political career encompass much of Alabama‘s territorial and early state history; he served in the Creek War, helped draft the state’s first constitution, and was the state’s first chief justice of its Supreme Court. His long political career included turns as a state legislator, U.S. congressman, governor, and U.S. senator.

Clement Comer Clay, 1835

Beginning his political career in Alabama as a leading member of the influential Broad River political machine, Clement Comer Clay (1789–1866) ultimately found favor with the voters of the state as a Jacksonian Democrat. His life and political career encompass much of Alabama‘s territorial and early state history; he served in the Creek War, helped draft the state’s first constitution, and was the state’s first chief justice of its Supreme Court. His long political career included turns as a state legislator, U.S. congressman, governor, and U.S. senator.

Clement Comer Clay was born in Halifax County, Virginia, on December 17, 1789, the son of William Clay, a plantation owner, and Rebecca Comer Clay. Around 1795, the family moved to Grainger County, Tennessee, in the northeastern part of the state. Clay attended Blount College (now the University of Tennessee), graduating in 1807, and read law in Knoxville. He was admitted to the State Bar at the end of 1809 and moved to the new town of Huntsville in the Mississippi Territory in November 1811 and opened a law practice. Clay served under Gen. Andrew Jackson in the Creek War of 1813-14 and in 1815 married Susanna Claiborne Withers, with whom he had three sons.

Clay quickly allied himself with the wealthy entrepreneurs transplanted from the Broad River area of Georgia who dominated Huntsville’s economy, a group headed by Huntsville Bank president LeRoy Pope and Pope’s son-in-law John W. Walker. Clay became a stockholder in and director of the Huntsville Bank and represented Madison County in the Alabama Territorial Legislature in 1818, where he joined Walker in pushing measures to strengthen the bank’s position, such as the elimination of limits on interest rates.

Constitutional Convention of 1819

At the Alabama constitutional convention of 1819, Walker was chosen as president, and he appointed Clay to chair the Committee of Fifteen that drafted the constitution. Clay fought successfully for life terms for judges but failed in his attempt to make it easier for the legislature to charter banks. The new state legislature elected Clay one of Alabama’s five circuit judges, who also jointly constituted the Alabama Supreme Court; the other judges then chose Clay as the state’s first chief justice.

Almost immediately, a nationwide financial crisis, which came to be known as the Panic of 1819, plunged the state into depression. Virtually all cases decided by the Supreme Court during Clay’s tenure involved actions to collect debts. Because of legislation that abolished usury limitations that Clay had supported, many of the debts carried enormous interest payments. At the end of 1823, Clay resigned from the bench to serve as an attorney for creditors in a case in which debtors challenged the validity of the exorbitant rates. In the first of what became known as the “big-interest” cases, the leader of Huntsville’s anti-bank forces, U.S. senator William Kelly, succeeded in convincing the state Supreme Court to limit the interest payments. Clay was succeeded as Chief Justice by Abner Smith Lipscomb.

Pursuing Public Office

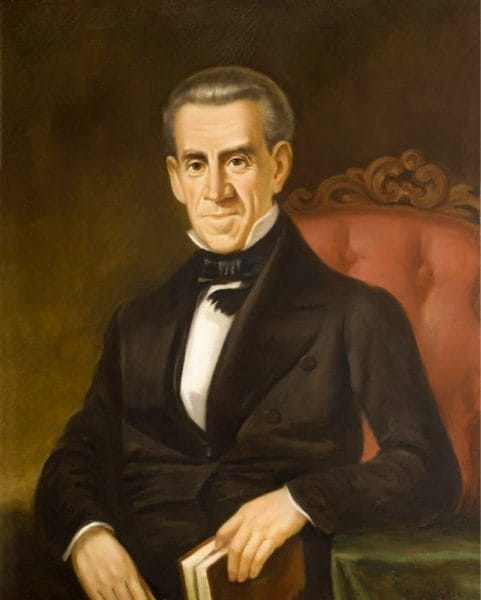

John McKinley

In 1825, Clay ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, but because of his association with banking and creditors, he was defeated overwhelmingly by small-farmer spokesman Gabriel Moore. He then decided to try to present a more appealing public image to poor voters, but his efforts to do so were initially quite clumsy. In 1826, he ran for the U.S. Senate against John McKinley, also a former supporter of the Huntsville Bank faction. Both Clay and McKinley now claimed to be ardent followers of Andrew Jackson, who had swept the state in the presidential election of 1824. At the same time that Clay and McKinley were opposing each other for the Senate, they were jointly the attorneys for the creditors in the second of what became known as the “big interest” cases. In this final round of the battle, the two men persuaded the Alabama Supreme Court that the statute of limitations barred debtors from recovery of the usurious interest they had already paid. Although he was victorious in the court case, Clay narrowly lost the election to McKinley when he tried to court the small number of legislators who supported John Quincy Adams, thus alienating a crucial number of Jacksonians.

John McKinley

In 1825, Clay ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, but because of his association with banking and creditors, he was defeated overwhelmingly by small-farmer spokesman Gabriel Moore. He then decided to try to present a more appealing public image to poor voters, but his efforts to do so were initially quite clumsy. In 1826, he ran for the U.S. Senate against John McKinley, also a former supporter of the Huntsville Bank faction. Both Clay and McKinley now claimed to be ardent followers of Andrew Jackson, who had swept the state in the presidential election of 1824. At the same time that Clay and McKinley were opposing each other for the Senate, they were jointly the attorneys for the creditors in the second of what became known as the “big interest” cases. In this final round of the battle, the two men persuaded the Alabama Supreme Court that the statute of limitations barred debtors from recovery of the usurious interest they had already paid. Although he was victorious in the court case, Clay narrowly lost the election to McKinley when he tried to court the small number of legislators who supported John Quincy Adams, thus alienating a crucial number of Jacksonians.

In 1828, Clay was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives and was unanimously chosen its speaker. He proceeded to push a series of anti-small-farm positions that were fraught with political danger. Alabama’s small farmers, like good Jacksonian Democrats everywhere, were vigorously anti-aristocrat, suspicious of the power of private corporations, and positively inflamed by any efforts to limit the power of their vote. Clay made several political mistakes, which included pricing the Muscle Shoals Canal land grant out of the reach of poor squatters, requiring non-slaveowners from patrolling duty for escaped enslaved people, and opposing amending the state constitution. In other actions, he favored repealing the law that prohibited participants in duels from holding public office, opposed efforts to secure married women their separate estates, and voted to extend the state’s jurisdiction over Creek Indian territory.

Clay again ran for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1829. His legislative opposition to low prices for the Muscle Shoals Canal land grant dogged his campaign, however. His opponent, who advocated reduced prices and squatters’ rights, carried the counties of the western Tennessee Valley. But Clay defeated him, sweeping his own Madison County, where enthusiasm was high for getting as much money as possible from the lands in order to finance the building of the proposed canal. Once in Congress, however, Clay enthusiastically embraced the cause of squatters and public land debtors, thus at last freeing himself from an identification with aristocratic beliefs. And with one exception—his vote to override President Jackson’s veto of the Maysville Road Bill—he never again deviated from the Jacksonian line. He continued to defend slavery as well and asserted that even a program of compensated emancipation would lead to southern secession.

Elected Governor

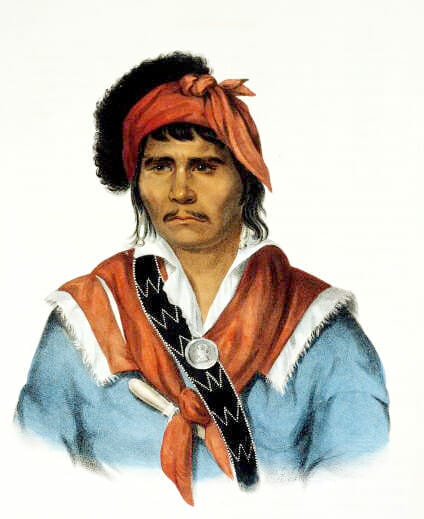

Neamathla

By his final term in the House, he had become chairman of the Committee on Public Lands and a leading advocate of the graduation and reduction of land prices and permanent preemptive rights for squatters. In 1835 Alabama Democrats nominated Clay for governor, and he defeated the Whig candidate, Enoch Parsons, by nearly two to one. His first message to the legislature was devoted largely to warning of the danger of abolitionism; he demanded that northerners who had mailed abolitionist pamphlets to the South be punished, and he urged strengthening laws against slave insurrection.

Neamathla

By his final term in the House, he had become chairman of the Committee on Public Lands and a leading advocate of the graduation and reduction of land prices and permanent preemptive rights for squatters. In 1835 Alabama Democrats nominated Clay for governor, and he defeated the Whig candidate, Enoch Parsons, by nearly two to one. His first message to the legislature was devoted largely to warning of the danger of abolitionism; he demanded that northerners who had mailed abolitionist pamphlets to the South be punished, and he urged strengthening laws against slave insurrection.

In the spring of 1836, desperate economic conditions among the Creek Confederacy drove some 3,000 of them to follow militant Hitchiti leader Neamathla into open revolt. Clay called out the state militia and took personal command of it. Most of the Creek Nation joined in the effort to suppress the rebellion. When U.S. forces under Gen. Thomas Jesup arrived in June, the revolt collapsed. Even though most of the Indians had actively opposed the revolt, Clay, in a gesture applauded by the great majority of Alabama voters, insisted that the federal government remove all of the Creeks and their Indian allies from the state immediately. The government complied, with federal troops escorting almost the entire population of the Creek Confederacy to lands in Oklahoma.

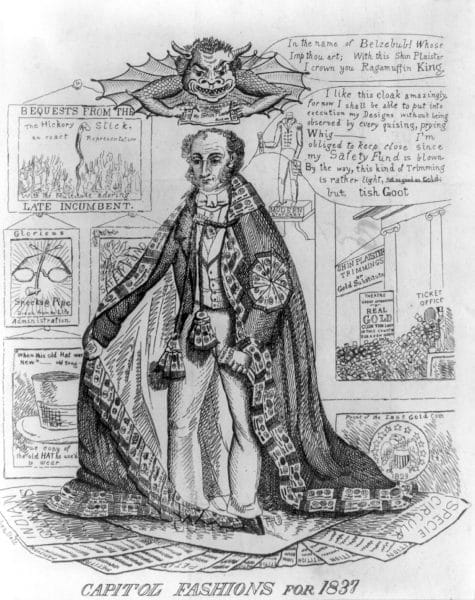

Panic of 1837 Political Cartoon

The following spring, Alabama began suffering the terrible effects of yet another national financial crisis—the Panic of 1837. Demonstrating his now firmly entrenched tendency toward demagoguery, Clay summoned the legislature into special session and pressed for radical measures to aid hard-pressed debtors, which they enacted in the form of the Relief Act of (June) 1837. The legislation required the state bank and its branches to suspend immediate collection of debts and provide debtors with three additional years in which to pay. Furthermore, the bank and its branches were ordered to sell some $5 million in state bonds to raise capital in order to make additional loans to desperate Alabamians. These extraordinarily foolish acts advanced Clay’s political career but left the state bank with vast debt and no means to service it. Grateful legislators—many of whom were themselves debtors to the Bank of Alabama—unanimously elected Clay to the U.S. Senate to succeed John McKinley, who had been appointed by Pres. Martin Van Buren to the U.S. Supreme Court. Clay resigned as governor and took his Senate seat in September 1837.

Panic of 1837 Political Cartoon

The following spring, Alabama began suffering the terrible effects of yet another national financial crisis—the Panic of 1837. Demonstrating his now firmly entrenched tendency toward demagoguery, Clay summoned the legislature into special session and pressed for radical measures to aid hard-pressed debtors, which they enacted in the form of the Relief Act of (June) 1837. The legislation required the state bank and its branches to suspend immediate collection of debts and provide debtors with three additional years in which to pay. Furthermore, the bank and its branches were ordered to sell some $5 million in state bonds to raise capital in order to make additional loans to desperate Alabamians. These extraordinarily foolish acts advanced Clay’s political career but left the state bank with vast debt and no means to service it. Grateful legislators—many of whom were themselves debtors to the Bank of Alabama—unanimously elected Clay to the U.S. Senate to succeed John McKinley, who had been appointed by Pres. Martin Van Buren to the U.S. Supreme Court. Clay resigned as governor and took his Senate seat in September 1837.

In the Senate, Clay renewed his crusade for squatters’ rights and the reduction of public land prices, urged the removal of the Cherokees to Oklahoma, and fought for the adoption of President Van Buren’s independent subtreasury scheme. The deepening depression, however, created such a crisis in Clay’s personal finances that he was forced to resign from the Senate in November 1841. In 1830, he had owned 52 enslaved people and about 1833 had purchased a second large plantation. By 1834, he owned 71 humans. But by 1840, he began a decade of selling those people to meet his debts.

Later Career

Benjamin Fitzpatrick

These financial reverses were accompanied by political ones. In 1842, Gov. Benjamin Fitzpatrick appointed Clay to prepare a digest of the state’s laws, but Clay’s political enemies in the legislature opposed its formal adoption. It was accepted only after a lengthy and embarrassing floor fight. In the summer of 1843, Fitzpatrick appointed Clay to the Alabama Supreme Court, but the following December, Whig and Calhounite Democrat legislators united to defeat Clay’s election to a full term. In 1846, Gov. Joshua L. Martin named Clay to the board that was supervising the liquidation of the Bank of Alabama, but in 1848 the legislature abolished the board, in part to deprive Clay of the office. After these successive humiliations, Clay retired from public life and devoted himself to his Huntsville law practice, in partnership with his sons. His eldest son, Clement Claiborne Clay, had launched a political career of his own, one that took him eventually to the U.S. and Confederate Senates.

Benjamin Fitzpatrick

These financial reverses were accompanied by political ones. In 1842, Gov. Benjamin Fitzpatrick appointed Clay to prepare a digest of the state’s laws, but Clay’s political enemies in the legislature opposed its formal adoption. It was accepted only after a lengthy and embarrassing floor fight. In the summer of 1843, Fitzpatrick appointed Clay to the Alabama Supreme Court, but the following December, Whig and Calhounite Democrat legislators united to defeat Clay’s election to a full term. In 1846, Gov. Joshua L. Martin named Clay to the board that was supervising the liquidation of the Bank of Alabama, but in 1848 the legislature abolished the board, in part to deprive Clay of the office. After these successive humiliations, Clay retired from public life and devoted himself to his Huntsville law practice, in partnership with his sons. His eldest son, Clement Claiborne Clay, had launched a political career of his own, one that took him eventually to the U.S. and Confederate Senates.

Despite his public pronouncements, Clay never genuinely accepted the pro-small farmer, anti-corporation heart of Jacksonian ideology. He espoused Jacksonian ideals almost entirely to advance his political career. By withdrawing from public life, he became free to resume the pro-plantation, pro-development attitudes that had characterized his early career. He helped lead in the creation of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad and became a large stockholder in it. He served as a delegate to two Southern Commercial Conventions and consistently spoke out strongly for slavery and southern rights. With the return of prosperity in the 1850s, his economic situation began to improve. By 1860, he owned 84 enslaved people, real estate worth $60,000, and personal property valued at $85,000. But Clay’s advocacy of secession and his son’s vigorous support of the Confederacy made the former governor a particular object of Unionist hostility during the Civil War. When federal forces occupied Huntsville at the end of 1864, Clay was imprisoned as a hostage. His time in jail broke Clay’s health. By the summer of 1865, he was an invalid. His wife, Susanna, died at the beginning of 1866, and he followed her on September 6, 1866.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Nuermberger, Ruth Ketring. The Clays of Alabama: A Planter-Lawyer-Politician Family. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1958.

- Thornton, J. Mills, III. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Lousiana State University Press, 1978.