John Kelly Fitzpatrick

John Kelly Fitzpatrick

Painter and educator John Kelly Fitzpatrick (1888-1953) devoted his career to presenting the life of his rural central Alabama home in his art. During the 1920s and throughout the Great Depression, Fitzpatrick focused his attention on Alabama's rural landscape and its inhabitants during a socially and economically turbulent period in the state's history. An artist, art teacher, and promoter of visual-arts organizations in the region, Fitzpatrick was one of the state's most prominent and important advocates for art and art education.

John Kelly Fitzpatrick

Painter and educator John Kelly Fitzpatrick (1888-1953) devoted his career to presenting the life of his rural central Alabama home in his art. During the 1920s and throughout the Great Depression, Fitzpatrick focused his attention on Alabama's rural landscape and its inhabitants during a socially and economically turbulent period in the state's history. An artist, art teacher, and promoter of visual-arts organizations in the region, Fitzpatrick was one of the state's most prominent and important advocates for art and art education.

John Kelly Fitzpatrick was born in Wetumpka, Elmore County, on August 15, 1888 to Phillips Fitzpatrick, a physician, and Jane Lovedy Fitzpatrick. Called "Kelly" by his family and friends, Fitzpatrick took pride in his lineage: his grandfather, Benjamin Fitzpatrick, was governor from 1841 to 1845 and later a U.S. Senator. Fitzpatrick attended Starke University School in Montgomery and the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa from 1908 to 1910 but did not graduate. In March 1918, he enlisted with the U.S. Army and served in France in World War I. Fitzpatrick was severely wounded by shrapnel during a battle in July of that year. As a result, he was permanently scarred on his face, neck, and chest. This experience colored his outlook profoundly, and he later wrote that his physical suffering caused him to lose interest in the material world and focus instead on the beautiful and spiritual aspects of life.

Fitzpatrick Heading Off to Paint

Fitzpatrick's artistic abilities and interests were apparent from childhood. He cultivated those interests as a young adult during a brief period of study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1912 and much later at the age of 37 at the Académie Julian in Paris. Beyond this minimal formal training, he acquired knowledge and appreciation of contemporary painting trends while traveling in Europe during both 1926 and 1930. He was inspired largely by Impressionist painters and Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh, and Henri Matisse, whose works were prominently featured in the Paris art world in the 1930s. Above all, Fitzpatrick adopted these French artists' love of brilliant color to structure his compositions and to create forms.

Fitzpatrick Heading Off to Paint

Fitzpatrick's artistic abilities and interests were apparent from childhood. He cultivated those interests as a young adult during a brief period of study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1912 and much later at the age of 37 at the Académie Julian in Paris. Beyond this minimal formal training, he acquired knowledge and appreciation of contemporary painting trends while traveling in Europe during both 1926 and 1930. He was inspired largely by Impressionist painters and Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh, and Henri Matisse, whose works were prominently featured in the Paris art world in the 1930s. Above all, Fitzpatrick adopted these French artists' love of brilliant color to structure his compositions and to create forms.

During the 1930s, Fitzpatrick was among the many American painters who participated in the New Deal programs that were designed to offer economic relief during the Great Depression. In 1933-34, he worked for the Public Works of Art Program, known as PWAP. He was assigned to make paintings in the category of "regional industries" for which he was paid $38.00 per week. In 1937-38, he was commissioned to paint murals for post offices in Ozark and Phenix City under the auspices of the Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture.

Fitzpatrick and Warree Carmichael LeBron

In addition to making art, Fitzpatrick devoted his time to teaching and promoting regional arts organizations such as the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts and the Alabama Art League. When the museum was founded in 1930, he was one of the original members of the board of directors and chaired the exhibitions committee. Through personal donations and assistance from his contacts in the federal relief programs, Fitzpatrick established the museum's original art collection, and it later became a repository for examples of his work. He was a popular and beloved art teacher, both as the director of the Montgomery Museum Art School and as an organizer of art colonies. Fitzpatrick, along with his friends Sallie B. Carmichael and her daughter Warree Carmichael LeBron, established the Dixie Art Colony in 1933. From 1937, it was housed at a Boy Scout camp named Camp Dixie on Lake Martin. Fitzpatrick, LeBron, and Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) art professor Frank Applebee were the primary instructors. The Colony last met in 1948 at Nobles Ferry, Elmore County. Kelly worked with one of the colonists, Genevieve Southerland of Mobile, to facilitate colonies that were held on the Alabama coast at Bayou La Batre in the mid-1940s and Coden in 1950, with Fitzpatrick serving to critique the works of the students rather than offer formal instruction. At each of these sites amateurs pursued their own love of painting under his guidance.

Fitzpatrick and Warree Carmichael LeBron

In addition to making art, Fitzpatrick devoted his time to teaching and promoting regional arts organizations such as the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts and the Alabama Art League. When the museum was founded in 1930, he was one of the original members of the board of directors and chaired the exhibitions committee. Through personal donations and assistance from his contacts in the federal relief programs, Fitzpatrick established the museum's original art collection, and it later became a repository for examples of his work. He was a popular and beloved art teacher, both as the director of the Montgomery Museum Art School and as an organizer of art colonies. Fitzpatrick, along with his friends Sallie B. Carmichael and her daughter Warree Carmichael LeBron, established the Dixie Art Colony in 1933. From 1937, it was housed at a Boy Scout camp named Camp Dixie on Lake Martin. Fitzpatrick, LeBron, and Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) art professor Frank Applebee were the primary instructors. The Colony last met in 1948 at Nobles Ferry, Elmore County. Kelly worked with one of the colonists, Genevieve Southerland of Mobile, to facilitate colonies that were held on the Alabama coast at Bayou La Batre in the mid-1940s and Coden in 1950, with Fitzpatrick serving to critique the works of the students rather than offer formal instruction. At each of these sites amateurs pursued their own love of painting under his guidance.

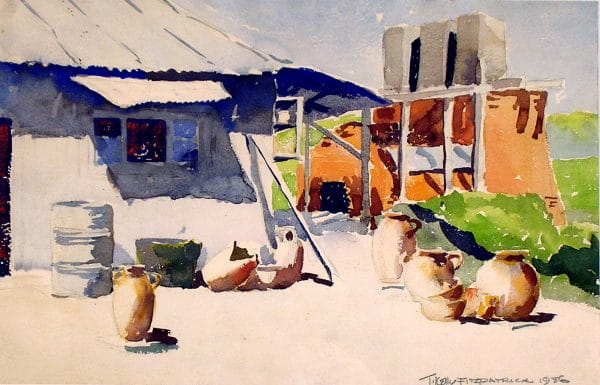

Monday Morning

Although he occasionally painted portraits and still-life compositions, Fitzpatrick's primary subject was the Alabama landscape, specifically the areas around his home in Elmore County. He painted rural dwellings, county crossroads settlements, and genre scenes that depict the day-to-day life of the predominantly black population that labored in agricultural activities in the area. Works such as Monday Morning (1935) exhibit Fitzpatrick's signature style—a light-filled composition dominated by the natural environment of trees, hills, and clouds, with the human inhabitants blending seamlessly into the landscape. The mule-drawn wagons seen in the painting, then still the primary form of transportation for rural peoples, were a common sight at the time. The strong shadows convey the midday heat of an Alabama summer, and the contrast created by their dark forms intensifies the brilliance of the color. Fitzpatrick did very little preliminary drawing when composing his paintings; instead he created his forms directly on the surface using a variety of brushstrokes ranging from short, choppy strokes to give a sense of weight and volume to his forms, to long, sweeping applications of paint for expanses of landscape and sky. He applied paint thickly and built up layers to create an uneven surface texture known as impasto.

Monday Morning

Although he occasionally painted portraits and still-life compositions, Fitzpatrick's primary subject was the Alabama landscape, specifically the areas around his home in Elmore County. He painted rural dwellings, county crossroads settlements, and genre scenes that depict the day-to-day life of the predominantly black population that labored in agricultural activities in the area. Works such as Monday Morning (1935) exhibit Fitzpatrick's signature style—a light-filled composition dominated by the natural environment of trees, hills, and clouds, with the human inhabitants blending seamlessly into the landscape. The mule-drawn wagons seen in the painting, then still the primary form of transportation for rural peoples, were a common sight at the time. The strong shadows convey the midday heat of an Alabama summer, and the contrast created by their dark forms intensifies the brilliance of the color. Fitzpatrick did very little preliminary drawing when composing his paintings; instead he created his forms directly on the surface using a variety of brushstrokes ranging from short, choppy strokes to give a sense of weight and volume to his forms, to long, sweeping applications of paint for expanses of landscape and sky. He applied paint thickly and built up layers to create an uneven surface texture known as impasto.

Fitzpatrick's approach to art, which he instilled in his students, reflected a larger trend in American painting of the pre-World War II period known as Regionalism. Embraced by the more conservative painters of that era, Regionalism was favored by artists who rejected the newly evolving movements of modernism and abstraction, such as Cubism, that had found favor with many artists in Europe and the New York art world. Artists who are identified as Regionalists promoted an art that was centered in realism and dominated by subjects that reflected populist values. This interpretation of American society reflected the views of the dominant white, Anglo-Saxon tradition and was rooted in land ownership and an idealized view of agrarian culture. Because his work's brilliant, clear color and form embodied the familiar light-filled, natural beauty of the state's topography, Fitzpatrick's work found immediate and lasting favor with his Alabama audience. However, beyond their physical beauty, there was also a popular perception that these images mirrored an ordered and peaceful social structure in a period during which the reality was quite different. Unlike the artists and documentary photographers who reacted to the nation's Great Depression of the 1930s by illustrating the deprivation and hardships that characterized life in rural Alabama, Kelly Fitzpatrick created a vision of contentment informed by his own positive perception of the land and its people, born of his standing in the community and his knowledge of its history. Inevitably, his optimistic state of mind led to compositions in which the artist's respect for and unexamined acceptance of the social structures of the past outweighed the reality of the times.

Fitzpatrick suffered a massive heart attack and died on April 18, 1953; he was buried in Wetumpka City Cemetery. Although he is not particularly well known beyond the borders of Alabama, Fitzpatrick left a substantial legacy in his native state. Many of his students practiced, taught, and promoted his philosophy and style of art well into the latter part of the twentieth century. His art is preserved in private and public collections around the state.

Further Reading

- John Kelly Fitzpatrick: Retrospective Exhibition. Montgomery: Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 1970.

- A Symphony of Color: The World of Kelly Fitzpatrick. Montgomery: Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 1991.

- Williams, Lynn Barstis. “The Dixie Art Colony.” Alabama Heritage (Summer 1996): 6-15.

- ———. “Another Provincetown? Alabama’s Gulf Coast Art Colonies at Bayou La Batre and Coden.” Gulf South Historical Review 15 (Spring 2000): 41–58.

- ———. The Bayou Painters: South Alabama’s Art Colony (1946-1953). Mobile: Mobile Museum of Art, 2006.