James Withers Sloss

James Withers Sloss (1820-1890) was a plantation owner, bookkeeper, merchant, and business owner. Sloss is particularly remembered for his work as a railroad president, coal operator, and iron manufacturer, and for his efforts in establishing the Pratt Coal and Coke Company and Sloss Furnaces. He became extremely wealthy through these endeavors. Although often referred to as “Colonel Sloss” in both primary and secondary documents, he has no record of military service.

Sloss was born in Mooresville, Limestone County, on April 7, 1820, to Joseph Long Sloss and Clarissa Wasson Sloss. He was the grandson of Robert and Ann Long Sloss and a cousin of Alabama politician and newspaper editor Joseph Humphrey Sloss. Sloss’s parents had emigrated to America in 1803, leaving behind their native homeland of Bellaghy, Ireland, and settling first in Virginia and later in Alabama. Joseph Long Sloss served in the War of 1812 and worked as a tailor, notably training future president Andrew Johnson in the craft of making frock suits.

After a limited education, Sloss became employed as an apprentice bookkeeper at age 15. He married Mary Bigger in Lauderdale County on November 26, 1844, and the couple would have nine children. Over the next six years, Sloss saved his earnings and purchased a store in Athens, Limestone County, in 1842. He expanded his merchant holdings to include several stores in north Alabama and multiple plantations. U.S. Federal Census Slave Schedules show that he claimed ownership of two enslaved individuals in 1850 and 11 by 1860.

Along with his mercantile holdings, his interest in and advocacy for railroads increased as the 1850s came to an end. He was granted an exemption from Civil War military service based on his position as president of the Tennessee and Alabama Central Railway of Limestone County. Following the war, the Southern, the Central, and the Tennessee and Alabama railroad companies merged to form the Nashville and Decatur Railroad on January 1, 1867. Sloss served as the first president of the company, which would later be consolidated into the Louisville & Nashville Railroad holdings. His work was influential in extending railroad lines south through Birmingham, Jefferson County, and Montgomery, Montgomery County, where they could connect to existing rail lines stretching to the Gulf Coast. Sloss moved his family to Birmingham sometime between 1870 and 1880. Following his wife Mary’s death in 1871, Sloss married Mattie Lundie of Oxford, Mississippi, in July 1872. They would have three children.

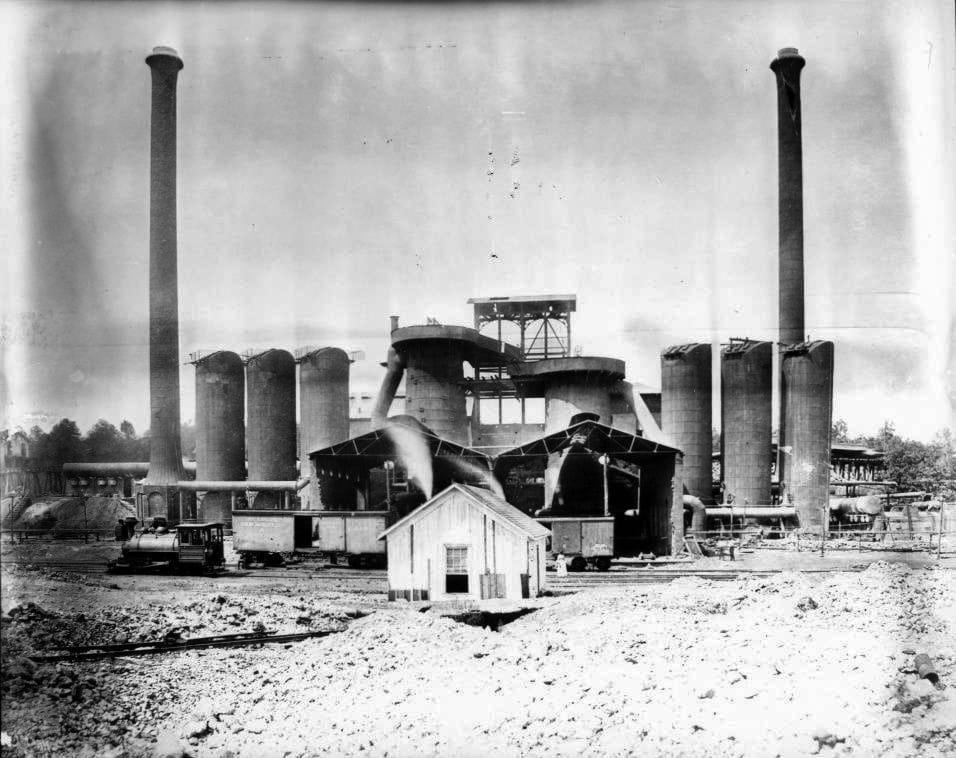

Sloss’s business interests grew to include mining and iron manufacturing. He formed a partnership with Birmingham businessman James Thomas, a native of Pennsylvania, to lease the Oxmoor furnace plant. The Brown coal seam (later known as the Pratt coal seam) then drew his attention, and he served as one of the managers of the Eureka Mining and Transportation Company in Birmingham, which produced coke pig iron. He joined Truman Aldrich and Henry F. DeBardeleben to form the first large coal company of Alabama, the Pratt Coal and Coke Company, south of Birmingham in 1878. Sloss served as both secretary and treasurer of the company but left the following year to focus on producing iron at Oxmoor furnaces. He formed the Sloss Furnace Company in 1881, with his sons Frederick and Maclin Sloss taking active roles. James W. Sloss would serve on the board of directors as the president of the company, and Frederick would serve as secretary and treasurer. The company built two furnaces on 50 acres of land in eastern Birmingham centrally located to take advantage of railway lines. The first furnace used two Whitwell stoves, each 60 feet tall with a span of 18 feet, to furnish the hot air blast. Sloss and his company, along with many industrialists of the period, have been scrutinized by historians for their almost exclusive use of unskilled African American laborers and convict labor leased from the state of Alabama.

Ore supply issues and the need for repeated changes and repairs to the furnaces’ operation created costly delays in production. This firm would eventually become the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company after Sloss sold the operation in 1886 for the sum of $2 million in cash. Several New York investors along with Georgia Pacific Railroad agent J. W. Johnson purchased the company, successfully growing the enterprise in the following years.

By 1883, Sloss had acquired the Potter mine in Bessemer, a site he had previously leased while mining red hematite. Sloss also acquired a large amount of land in the Birmingham area that included much of Ruffner Mountain and Red Mountain. In 1888, Sloss bought controlling interest in the Hog Mountain gold mine in Dadeville, Tallapoosa County. He was elected a director of the Alabama National Bank in 1890. That same year, The Florence Herald described him as the “second wealthiest man in the state.” In 1891, he was listed as a member of the board of directors and secretary of the Jefferson Mining Company.

In addition to his business interests, Sloss was involved in both political and civic affairs. He served as president of the Lake DeFuniak Chautauqua Association, a Florida organization dedicated to improving education in the South. He was a Methodist and Sunday school superintendent of the First Methodist Episcopal Church in Birmingham. A Democrat, Sloss was acquainted through his business ventures with George S. Houston, president of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad and later governor of Alabama from 1874-78. Although he was involved in local and state politics, he appears to have never held political office, although he was encouraged to run for governor. He reportedly donated generously to charities, as well as to the Methodist church.

Sloss died from heart failure on May 4, 1890, and was interred in Oak Hill Cemetery in Birmingham. Obituaries credited him with having a lasting impact on Birmingham’s growth and status as the “Magic City,” and estimated the worth of his estate as being $2,000,000. Sloss Furnace was named a National Historic Landmark in 1981, though very little remains of the original structures from the period of Sloss’s ownership. The site serves as an industrial historic site and museum open to the public.

Further Reading

- Cruikshank, George M. A History of Birmingham and Its Environs. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1920.

- Lewis, W. David. Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham District: An Industrial Epic. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.