Marble Industry

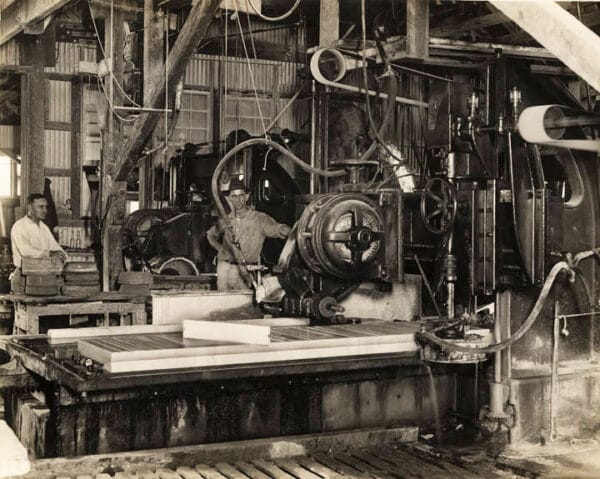

Marble Polishing at Alabama Marble in Sylacauga

Alabama marble is among the highest quality stone in the world. It has been an important component of the state’s mining industry since the 1830s, although the uses for the stone have changed over time. Centered around Sylacauga, Talladega County, the state’s marble resources were first made famous by Italian sculptor Giuseppe Moretti, and stone from the quarries there was sculpted into a bust of Abraham Lincoln displayed in the U.S. Capitol building and used to construct the Lincoln Memorial and the U.S. Supreme Court building. Alabama marble occurs in shades of white, pink, gray, red, and black, but the white marble of Sylacauga has consistently drawn the most acclaim and earned the town the sobriquet “the Marble City.”

Marble Polishing at Alabama Marble in Sylacauga

Alabama marble is among the highest quality stone in the world. It has been an important component of the state’s mining industry since the 1830s, although the uses for the stone have changed over time. Centered around Sylacauga, Talladega County, the state’s marble resources were first made famous by Italian sculptor Giuseppe Moretti, and stone from the quarries there was sculpted into a bust of Abraham Lincoln displayed in the U.S. Capitol building and used to construct the Lincoln Memorial and the U.S. Supreme Court building. Alabama marble occurs in shades of white, pink, gray, red, and black, but the white marble of Sylacauga has consistently drawn the most acclaim and earned the town the sobriquet “the Marble City.”

Geologically speaking, marble is a metamorphic rock that derives from limestone (a sedimentary rock) subjected to extreme heat, which changes its structure. Marble is very fine grained and more durable than limestone, which is also a popular building material. Marble is plentiful in the east-central part of the state, principally in Bibb, Calhoun, Clay, Coosa, Etowah, Lee, Macon, St. Clair, and Shelby counties. Sylacauga’s marble bed is approximately 32 miles long, 1.5 miles wide, and 400 feet deep.

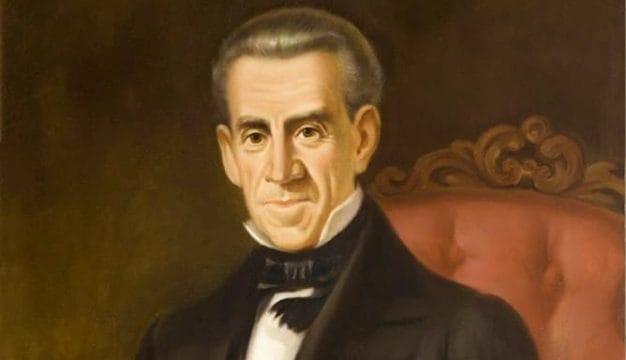

The first person to exploit Alabama’s marble resources was physician Edward Gantt, who in around 1814 spotted large deposits of marble while traveling through present-day Sylacauga with Gen. Andrew Jackson. Gantt returned to the area in 1834 and bought a large amount of land with significant marble deposits and entered into a partnership with several other men to develop a quarry. Gantt eventually became involved in several quarries and the marble industry until his death in 1867.

Sylacauga Marble Operation, ca. 1930s

The George Herd Family bought several quarries and established the first successful mining operation in the mid-1830s, in Sylacauga, and sold the first quarried marble from the area in 1838. The business mostly shipped the marble in and around central Alabama. Tombstones were the primary use of the stone, but the business advertised a number of uses. In consequence, a moderately successful community grew around the area of Talladega County. By the 1880s, the marble industry, with roughly a dozen cooperative ventures and countless independent miners in Talladega and the neighboring counties, was an established, central facet of mining in the state. The last decades of the nineteenth century saw a dramatic increase in the demand for marble owing to a revival of neoclassical architectural, which featured many elements traditionally fashioned from marble. Alabama marble was popular for both building and sculpting, and companies shipped their products throughout the United States. Mining operations were typically able to meet the demand. As production increased and the industry grew, more towns, such as Sylacauga, Gantt’s Quarry, and Dolomite, grew around mining operations in the state.

Sylacauga Marble Operation, ca. 1930s

The George Herd Family bought several quarries and established the first successful mining operation in the mid-1830s, in Sylacauga, and sold the first quarried marble from the area in 1838. The business mostly shipped the marble in and around central Alabama. Tombstones were the primary use of the stone, but the business advertised a number of uses. In consequence, a moderately successful community grew around the area of Talladega County. By the 1880s, the marble industry, with roughly a dozen cooperative ventures and countless independent miners in Talladega and the neighboring counties, was an established, central facet of mining in the state. The last decades of the nineteenth century saw a dramatic increase in the demand for marble owing to a revival of neoclassical architectural, which featured many elements traditionally fashioned from marble. Alabama marble was popular for both building and sculpting, and companies shipped their products throughout the United States. Mining operations were typically able to meet the demand. As production increased and the industry grew, more towns, such as Sylacauga, Gantt’s Quarry, and Dolomite, grew around mining operations in the state.

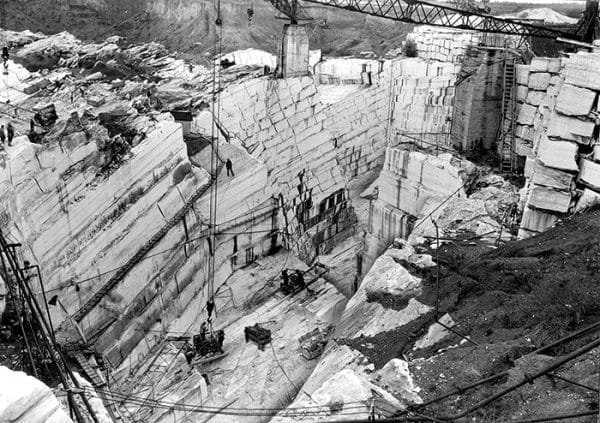

Marble Quarry, 1935

Workers coming into communities like Sylacauga were typically individuals from larger mining operations in the region who sought better conditions, but those who specialized in marble tended to be advanced craftsmen with advanced quarrying tools and machinery. Although some of these workers were native to the region, many more came from Europe, particularly Italy, after artists like Moretti grew to prominence in Alabama. During periodic downturns, however, marble workers tended to join in protests and strikes. Even during boom periods, contention often arose between miners and owners over community issues, such as local taxes and “community improvement” fees. Both the operations and labor contention in Alabama mining were typical of national trends.

Marble Quarry, 1935

Workers coming into communities like Sylacauga were typically individuals from larger mining operations in the region who sought better conditions, but those who specialized in marble tended to be advanced craftsmen with advanced quarrying tools and machinery. Although some of these workers were native to the region, many more came from Europe, particularly Italy, after artists like Moretti grew to prominence in Alabama. During periodic downturns, however, marble workers tended to join in protests and strikes. Even during boom periods, contention often arose between miners and owners over community issues, such as local taxes and “community improvement” fees. Both the operations and labor contention in Alabama mining were typical of national trends.

The tools used in extracting the stone advanced rapidly through the 1880s and 1890s. The industry began with a focus on the industrial uses for marble, especially as flux in purifying steel. It was dynamited out of the ground or rock, sawed into smaller chunks, and ground into granules. The process required simple tools that left the product scratched and jagged. After the turn of the century invention of carborundum, a type of grinding material, grinding blades replaced steel saws and allowed for more precise cuts. By the mid-1930s, electricity replaced steam engines for running saws and diamond blades replaced carborundum, leading to a vast increase in marble output.

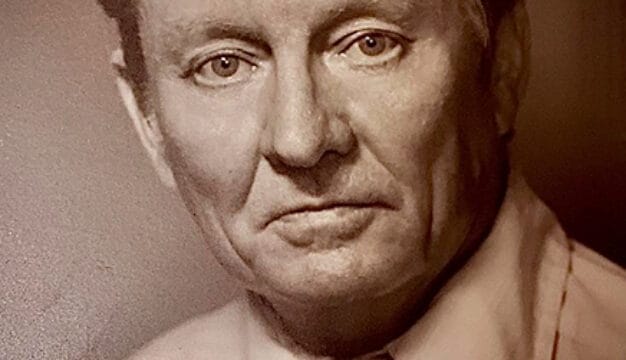

Giuseppe Moretti

Italian sculptor Giuseppe Moretti is the individual probably most associated with Alabama’s marble industry. He arrived in Alabama in 1903 and changed the face of the marble industry in a number of important ways. Moretti first encountered Alabama marble while working on a commission for Birmingham‘s cast-iron Vulcan statue, that city’s contribution to the St. Louis Exposition. He created a marble piece for the expo as well — the Head of Christ— which captured as much attention as Vulcan. (A favorite of Moretti’s, it currently resides on the third-floor landing of the main staircase at the Alabama Department of Archives and History in Montgomery.) Moretti established a studio near Sylacauga and soon convinced investors to join him in developing a marble quarry. He made several attempts at quarrying, the most successful being the Moretti-Harrah Marble Company, with partner C. J. Harrah formed in the early 1920s. Moretti continued sculpting commissions and acquired several financial backers, but he often lacked the business acumen to capitalize on them.

Giuseppe Moretti

Italian sculptor Giuseppe Moretti is the individual probably most associated with Alabama’s marble industry. He arrived in Alabama in 1903 and changed the face of the marble industry in a number of important ways. Moretti first encountered Alabama marble while working on a commission for Birmingham‘s cast-iron Vulcan statue, that city’s contribution to the St. Louis Exposition. He created a marble piece for the expo as well — the Head of Christ— which captured as much attention as Vulcan. (A favorite of Moretti’s, it currently resides on the third-floor landing of the main staircase at the Alabama Department of Archives and History in Montgomery.) Moretti established a studio near Sylacauga and soon convinced investors to join him in developing a marble quarry. He made several attempts at quarrying, the most successful being the Moretti-Harrah Marble Company, with partner C. J. Harrah formed in the early 1920s. Moretti continued sculpting commissions and acquired several financial backers, but he often lacked the business acumen to capitalize on them.

The Moretti-Harrah Company successfully grew and absorbed a number of smaller operations. And in 1908, the Alabama Marble Company was established on the site of the former Gantt Quarry. The two companies began to dominate the industry in Alabama. Quarrying marble continued to be profitable even through the Great Depression, and most companies in Alabama sold out to either Moretti-Harrah or Alabama Marble. In the 1940s, outside companies began to buy up Alabama firms, and both Moretti-Harrah and Alabama Marble become partners with Georgia firms in the 1960s; Moretti-Harrah partnered with Cyprus Thompson Weinman, and Alabama Marble merged with the Georgia Marble Company. (In 1988, English China Clays International purchased Moretti-Harrah and in 1989 purchased Cyprus Thompson Weinman. Then, Georgia Marble Company purchased Cyprus Thompson Weinman.)

Sylacauga Marble Quarry

In 1967, Alabama Marble’s structural operations shut down, no longer producing slabs for building material. The company continues to grind and extract minerals from the stone, especially calcium carbonate, for a variety of uses, including agricultural products, paints, and pharmaceuticals. The last major consolidation of the industry occurred when French mining corporation Imerys bought the Georgia Marble Company in 1995, and acquired English China Clays in 1999. In 2000, the National Labor Relations Board forced Imerys to recognize unions in its American subsidiaries. Three years later, Imerys sold its dimension stone properties to the Canadian Polycor Company, but Imerys still produces calcium carbonate outside Sylacauga at the largest operating calcium carbonate mine in the world. Polycor has 450 employees at 5 plants and 25 quarries that produce about 1.5 million cubic feet of marble per year, the majority coming from Georgia and Alabama. Another company, Omya Alabama Inc., produces fine calcium carbonate filler and coating grades for paper and packaging manufacturers. Although an Alabama Marble Company still exists, it is not the same as the original company of that name and produces only dimension stone. With an average revenue of roughly $12.5 million, the marble industry continues to thrive in Alabama.

Sylacauga Marble Quarry

In 1967, Alabama Marble’s structural operations shut down, no longer producing slabs for building material. The company continues to grind and extract minerals from the stone, especially calcium carbonate, for a variety of uses, including agricultural products, paints, and pharmaceuticals. The last major consolidation of the industry occurred when French mining corporation Imerys bought the Georgia Marble Company in 1995, and acquired English China Clays in 1999. In 2000, the National Labor Relations Board forced Imerys to recognize unions in its American subsidiaries. Three years later, Imerys sold its dimension stone properties to the Canadian Polycor Company, but Imerys still produces calcium carbonate outside Sylacauga at the largest operating calcium carbonate mine in the world. Polycor has 450 employees at 5 plants and 25 quarries that produce about 1.5 million cubic feet of marble per year, the majority coming from Georgia and Alabama. Another company, Omya Alabama Inc., produces fine calcium carbonate filler and coating grades for paper and packaging manufacturers. Although an Alabama Marble Company still exists, it is not the same as the original company of that name and produces only dimension stone. With an average revenue of roughly $12.5 million, the marble industry continues to thrive in Alabama.

Additional Resources

Carpenter, Gabe. “Sylacauga Marble World Renown.” The Daily Home, July 17, 2005, p. 3.

Dodd, Ed. “A Brief History of the Marble Industry in Sylacauga.” Alabama Heritage 20 (Spring 1991): 35-38.