Mining Labor

Striking Mine Workers

Mining operations in Alabama have focused primarily on the extraction of iron ore and coal. These raw materials, combined with limestone, constitute the key ingredients in the production of pig iron and steel. The existence of all three components within a 10-mile radius of Jones Valley contributed to the meteoric growth of the region around Birmingham—The Magic City. As Alabama’s early iron and coal industry recovered in the wake of the Civil War and Reconstruction, production boomed. Increased outputs of coal, coke, and pig iron in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries resulted in an influx of skilled and unskilled labor into the Birmingham District. Typically, workers bore the brunt of owners’ attempts to reduce operating costs, and they sought to organize in order to protect their interests. As union representatives lobbied for collective bargaining, the labor movement tended to focus on Alabama miners.

Striking Mine Workers

Mining operations in Alabama have focused primarily on the extraction of iron ore and coal. These raw materials, combined with limestone, constitute the key ingredients in the production of pig iron and steel. The existence of all three components within a 10-mile radius of Jones Valley contributed to the meteoric growth of the region around Birmingham—The Magic City. As Alabama’s early iron and coal industry recovered in the wake of the Civil War and Reconstruction, production boomed. Increased outputs of coal, coke, and pig iron in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries resulted in an influx of skilled and unskilled labor into the Birmingham District. Typically, workers bore the brunt of owners’ attempts to reduce operating costs, and they sought to organize in order to protect their interests. As union representatives lobbied for collective bargaining, the labor movement tended to focus on Alabama miners.

Demographics

Individuals using rudimentary methods tapped the region’s ore and coal veins as early as 1798, when the U.S. Congress established the Mississippi Territory. Extraction techniques remained primitive through the early nineteenth century as prospectors bought and leased enslaved people for labor and put them to work following readily accessible seams. Manpower shortages during the Civil War forced mine owners to rely more heavily on unskilled enslaved labor in order to meet wartime demands. In fact, the Confederacy’s construction of a naval yard, arsenal, and ordnance works at Selma resulted in increased iron and coal production. However, emancipation and war’s end devastated the state’s iron and coal industry.

DeBardeleben Coal Mines

A resurgence occurred in the 1870s when iron-makers decided to convert their primary fuel from charcoal to coke. Coke, a derivative of coal, proved cheaper and produced more energy than charcoal, facilitating high-volume production. Consequently, several entrepreneurs sought to revitalize Alabama’s iron and coal fields. For example, Henry Fairchild DeBardeleben founded the Eureka Mining and Transportation Company (1872); James W. Sloss established the Sloss Furnace Company (1881); and Joseph and William Woodward organized the Woodward Iron Company (1883). In 1886, the Chattanooga-based Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company extended its influence into the Birmingham District. These efforts contributed to increased pig iron production from 11,000 tons in 1872 to 800,000 tons in 1890. Similarly, coal extractions improved from 13,000 tons in 1870 to 5.5 million tons 20 years later. By the turn of the twentieth century, Alabama ranked third in coke production, fourth in pig iron yield, and fifth in both coal and steel output. Coal production doubled from 1900 to 1910, reaching a total value of $37.3 million by 1920.

DeBardeleben Coal Mines

A resurgence occurred in the 1870s when iron-makers decided to convert their primary fuel from charcoal to coke. Coke, a derivative of coal, proved cheaper and produced more energy than charcoal, facilitating high-volume production. Consequently, several entrepreneurs sought to revitalize Alabama’s iron and coal fields. For example, Henry Fairchild DeBardeleben founded the Eureka Mining and Transportation Company (1872); James W. Sloss established the Sloss Furnace Company (1881); and Joseph and William Woodward organized the Woodward Iron Company (1883). In 1886, the Chattanooga-based Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company extended its influence into the Birmingham District. These efforts contributed to increased pig iron production from 11,000 tons in 1872 to 800,000 tons in 1890. Similarly, coal extractions improved from 13,000 tons in 1870 to 5.5 million tons 20 years later. By the turn of the twentieth century, Alabama ranked third in coke production, fourth in pig iron yield, and fifth in both coal and steel output. Coal production doubled from 1900 to 1910, reaching a total value of $37.3 million by 1920.

As the region’s industrial base grew, skilled and unskilled workers migrated to the mines and furnaces of north-central Alabama. The 1890 Census identified approximately one-third (34.9 percent) of the mining labor force as native-born whites. Of the remaining workforce, 46.2 percent were black and 18.7 percent were foreign-born immigrants. The mining population increased from 11,751 in 1900 to 24,000 in 1930, peaking at 26,200 in 1920. By that year, more than 200 coal mines operated in a dozen counties, but two-thirds of the miners lived and worked in Jefferson and Walker Counties. Close proximity, family ties, common hazards, safety concerns, and meager wages unified white and black miners in their quest for equal pay for equal work. Furthermore, the miners’ ability to transcend racial barriers resulted in working-class solidarity that prompted 50 years of organizing efforts. Beginning with the earliest attempts at large-scale mining operations, coal miners were exploited by mine owners, with little chance of improving their working conditions. Work was brutally hard, and frequent accidents and explosions killed some miners and left others injured or maimed.

Unionizing

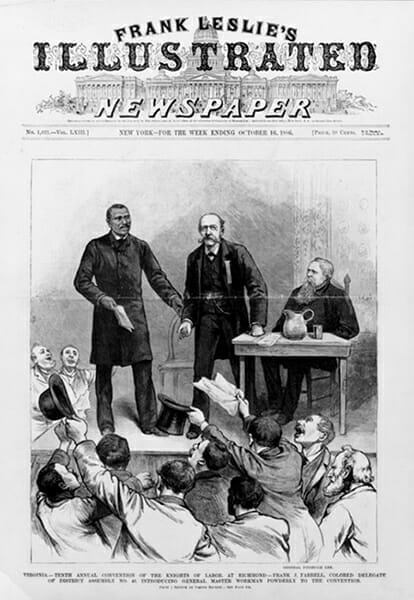

Knights of Labor Meeting

The coal industry was the focus of some of the earliest local efforts to unionize workers. In Jefferson County, miners from two companies struck in 1879 to protest wage reductions, and the Coketon strike of 1880 challenged company regulations that required miners to pay for hauling coal from the mines. Such strikes were generally ineffective given the widespread availability of excess labor in the form of convicts, foreign immigrants, and black workers as strikebreakers. Nevertheless, these early attempts at collective action marked the beginnings of organized labor in Alabama. In 1878, the Greenback-Labor Party (GLP) marked the first political body that specifically courted labor. Candidates and supporters combined union rhetoric with evangelical zeal to promote cooperation among white and black workers, appealing for political action based on class rather than on race. By mid-1878, the GLP had created nine local organizations, with six others in the developmental stage. Attempting to build on the GLP’s limited success, several hundred miners formed the Miners’ Union and Anti-Convict League in 1885. Meanwhile, William Sewell established an Alabama chapter of the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, which advocated an eight-hour day, abolition of convict labor, arbitration of disputes, monetary redistribution, and land reform. Discouraging strikes, leaders promoted cooperation and mutual support between labor and management. The Knights of Labor peaked in popularity in 1886 but then experienced a decline that coincided with a nationwide trend following Chicago’s Haymarket riot between police and striking workers, some of whom were believed to be anarchists.

Knights of Labor Meeting

The coal industry was the focus of some of the earliest local efforts to unionize workers. In Jefferson County, miners from two companies struck in 1879 to protest wage reductions, and the Coketon strike of 1880 challenged company regulations that required miners to pay for hauling coal from the mines. Such strikes were generally ineffective given the widespread availability of excess labor in the form of convicts, foreign immigrants, and black workers as strikebreakers. Nevertheless, these early attempts at collective action marked the beginnings of organized labor in Alabama. In 1878, the Greenback-Labor Party (GLP) marked the first political body that specifically courted labor. Candidates and supporters combined union rhetoric with evangelical zeal to promote cooperation among white and black workers, appealing for political action based on class rather than on race. By mid-1878, the GLP had created nine local organizations, with six others in the developmental stage. Attempting to build on the GLP’s limited success, several hundred miners formed the Miners’ Union and Anti-Convict League in 1885. Meanwhile, William Sewell established an Alabama chapter of the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, which advocated an eight-hour day, abolition of convict labor, arbitration of disputes, monetary redistribution, and land reform. Discouraging strikes, leaders promoted cooperation and mutual support between labor and management. The Knights of Labor peaked in popularity in 1886 but then experienced a decline that coincided with a nationwide trend following Chicago’s Haymarket riot between police and striking workers, some of whom were believed to be anarchists.

From 1887 to 1890, the Alabama Union Labor Party (later the Labor Party of Alabama), the National Federation of Miners and Mine Laborers, and the Miners’ Trade Council (formerly the Miners’ and Mine Laborers’ State Trades Council of Alabama) attempted to support miners’ interests but failed to garner sufficient influence within the state. Meanwhile, miners continually advocated for equal pay for equal work. They insisted that all mine work—including laying tracks, constructing guard rails, and hauling coal to tram cars—contributed to the overall production of coal. On the other hand, owners reaped no monetary benefits from preparation efforts or supporting tasks. Therefore, they contended that coal alone generated profits and that miners needed to work as efficiently as possible to maximize output.

Interracial Movement

Both the Greenbackers and the Knights of Labor contributed to an interracial movement that combined labor organization and political activism. Within this framework, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) emerged as the predominant labor organization of the 1890s. Although the UMWA adopted the interracial stance of its predecessors, white miners typically refused to interact or work with black miners.

The UMWA succeeded in its initial organizational drive in Alabama and in passing the Mine Inspection Act of 1890 to help reduce accidents. When the organization invited mine owners to revise a national wage scale, however, most refused to recognize the union, and only a few independent owners participated in the meetings. Consequently, union officials initiated a national strike for recognition in November 1890. The effort failed, and support for the UMWA in Alabama vanished. Nevertheless, the 1890 strike set the tone for labor conflicts for the next four decades. Common class interests brought coal miners together in interracial labor organizations, but operators used black strikebreakers (“scabs”) to drive a racial wedge between white and black workers. Unity persisted among the miners, but they were unprepared to deal with evictions from company housing, armed guards, and negative press coverage.

In the absence of the UMWA, miner representatives organized the United Mine Workers of Alabama (UMW-Alabama) in 1893. Austere economic conditions—falling prices, decreasing wages, and declining demand—precipitated by the Panic of 1893 prompted a strike the following year. Miners wanted to weigh coal cars before dumping, appoint their own people to confirm tonnage, and reduce house rents, store prices, and medical costs in company-owned facilities. Again, the strike failed, but demographics within Alabama’s coal mining industry began to change. As many white miners deserted the central Alabama fields to seek work elsewhere, many of the immigrant and black strikebreakers remained. Consequently, black miners constituted more than half of the state’s miners, and interracial cooperation became more critical to collective action.

Outlook Improves at the Turn of the Century

An economic upswing in 1897 improved the outlook for union organizers. Union success in midwestern coal fields encourage the UMWA to renew its recruiting efforts in Alabama, and the UMW-Alabama returned to its role as District 20 within the UMWA. Stimulated by the Spanish-American War, demand for coal increased in 1898, and a degree of prosperity returned to miners and operators. As a result, owners worked openly with UMWA representatives. From 1897 to 1903, the union experienced tacit recognition as it negotiated annual contracts. Furthermore, the UMWA constituted the core element in the newly formed Alabama Federation of Labor, which was established in 1900 to centralize union organizing and activities in the state.

Despite these successes, Alabama mine owners continued to use growing popular support for Jim Crow legislation to divide mine workers and oppose the efforts of the UMWA. They were aided in this effort by the adoption of the 1901 Constitution, which codified segregationist policies in Alabama. Contract negotiations failed, and in 1904, workers struck again, pitting themselves against the operators once more. Government officials sided with the owners, however. Basking in another victory, owners ignored union contracts, reduced wages, and fired union-affiliated workers. Similar events transpired in 1908, and operators, politicians, and newspaper editors attacked the UMWA for supporting an integrated workforce. Having spent more than $400,000 of miners’ dues to sustain the strike for two months, the union faced total defeat and once more lost its support in the Alabama coal fields.

Banner Mine Tragedy

In addition to denying union recognition, company officials maintained control over the labor force by employing “company unions” and private police forces, blacklisting all union supporters to exert their dominance and adopting aspects of welfare capitalism. However, the downside of their overwhelming success in crushing the strike of 1908 was a perennial labor shortage. Most skilled white miners left Alabama for northern and midwestern coal fields, and unskilled strikebreakers increased production costs because of inefficiency. The search for skilled workers focused initially on European immigrants, but non-competitive wages and segregation deterred widespread migration southward. Therefore, operators sought cheap labor among impoverished African Americans to reduce costs and to minimize the threat of unionism. Moreover, the convict-lease system continued to serve as a ready-made strike-breaking tool for mine owners. These labor conditions kept the focus off of safety and workers’ rights, leading to more accidents and health hazards. On April 8, 1911, an explosion at the Banner Mine in Jefferson County caused the largest loss of life to date in a mining accident, with 128 dead. Of that total, 125 were convicts leased to the mine as cheap labor.

Banner Mine Tragedy

In addition to denying union recognition, company officials maintained control over the labor force by employing “company unions” and private police forces, blacklisting all union supporters to exert their dominance and adopting aspects of welfare capitalism. However, the downside of their overwhelming success in crushing the strike of 1908 was a perennial labor shortage. Most skilled white miners left Alabama for northern and midwestern coal fields, and unskilled strikebreakers increased production costs because of inefficiency. The search for skilled workers focused initially on European immigrants, but non-competitive wages and segregation deterred widespread migration southward. Therefore, operators sought cheap labor among impoverished African Americans to reduce costs and to minimize the threat of unionism. Moreover, the convict-lease system continued to serve as a ready-made strike-breaking tool for mine owners. These labor conditions kept the focus off of safety and workers’ rights, leading to more accidents and health hazards. On April 8, 1911, an explosion at the Banner Mine in Jefferson County caused the largest loss of life to date in a mining accident, with 128 dead. Of that total, 125 were convicts leased to the mine as cheap labor.

Wartime Changes

The onset of World War I in Europe further siphoned skilled labor from central Alabama mines as European immigrants returned to their homeland to fight for their native countries and northern industrialists looked to the South for workers. The subsequent Great Migration of southern black workers to northern coal fields forced local operators to hire and train unskilled laborers from the Black Belt. As markets expanded during the war, these miners negotiated for better wages, working conditions, and overall treatment. The UMWA responded with a recruitment drive in 1917 that resulted in 128 new local organizations and 23,000 union members among the district’s 25,000 miners.

Emboldened by Pres. Woodrow Wilson’s commitment to peaceful labor relations, the UMWA issued an ultimatum to coal operators in the summer of 1917. In addition to union recognition, miners demanded reinstatement of discharged miners, an eight-hour day, a wage increase, union-approved tonnage inspectors, and semi-monthly payments in cash. In response, Harry Garfield, head of the federal Fuel Administration, proposed that miners realize all of their demands except for union recognition. Members of the Alabama Coal Operators’ Association resisted compliance, however. They agreed to discuss issues with government representatives but refused to negotiate with union officials.

The lack of federal oversight compromised the “Garfield Agreement,” and small strikes ensued at some Alabama mines in 1918 and 1919. Continued miner unrest prompted UMWA president John L. Lewis to call for a nationwide strike in 1920. Recognizing that more than three-fourths of Alabama miners were black, operators again accused unions of pro-integrationist actions. They imported strikebreakers, evicted miners and families, blacklisted strikers, courted public opinion, and maintained production. Alabama governor Thomas Kilby declared the strike “illegal and immoral” and supported the operators on every count. He granted neither union recognition nor wage increases, and he refused to reinstate striking miners. Decimated by Kilby’s decision, the UMWA again lost its base in Alabama. Miners, left with few options, generally opted to migrate northward to other coal fields.

Labor Legislation

Birmingham Coal Miners, 1937

Union organizing returned to Alabama in the 1930s, invigorated by the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933 and the National Labor Relations Act in 1935. With this legislation and with federal and state support, the UMWA resurrected District 20 and organized 100 percent of the state’s miners within two months. Ultimately, the New Deal legislation, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), and World War II boosted union preeminence, with the UMWA becoming the exclusive bargaining agent for coal miners until the Taft-Hartley Act levied restrictions in 1947.

Birmingham Coal Miners, 1937

Union organizing returned to Alabama in the 1930s, invigorated by the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933 and the National Labor Relations Act in 1935. With this legislation and with federal and state support, the UMWA resurrected District 20 and organized 100 percent of the state’s miners within two months. Ultimately, the New Deal legislation, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), and World War II boosted union preeminence, with the UMWA becoming the exclusive bargaining agent for coal miners until the Taft-Hartley Act levied restrictions in 1947.

Meanwhile, UMWA president Lewis mechanized the coal-mining industry even though it cost many miners their jobs. By the 1920s, coal faced competition from other fuel sources. Increasing demand for natural gas and petroleum products challenged operators to produce more coal with less labor and thereby lower costs of production. Ironically, although the 1920s was an era of increased union power, mechanization introduced during this period began to chip away at the number of jobs in the mining industry. The steam-powered puncher, electric coal cutter, and continuous miner revolutionized mining methods. As mechanization developed further, surface mining replaced underground mining as the preferred method of extraction. Volume production, relatively low labor costs, and improved safety records contributed to surface mining’s profitability and success, although the process caused serious environmental degradation and pollution.

In the twenty-first century, many mining problems persist. Labor costs, safety requirements, and environmental legislation have increased the overall expense of coal extraction. Many companies have moved their operations to the western United States or to South America. Consequently, many of Alabama’s coal fields lie dormant. Current reports indicate that coal underlies 9,700 square miles of state land, encompassing 3.1 billion tons of recoverable reserves. Accidents and explosions remain a threat in the mineral region of north-central Alabama, but miners, now unionized, continue to extract coal in more than 50 mining operations.

Additional Resources

Brown, Edwin L., and Colin J. Davis. It is Union and Liberty: Alabama Coal Miners and the UMW. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

Kelly, Brian. Race, Class, and Power in the Alabama Coalfields, 1908-21. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Letwin, Daniel. The Challenge of Interracial Unionism: Alabama Coal Miners, 1878-1921. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Taft, Philip. Organizing Dixie: Alabama Workers in the Industrial Era. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1981.

Ward, Robert David and William Warren Rogers. Labor Revolt in Alabama: The Great Strike of 1894. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1965.

Worthman, Paul B. “Black Workers and Labor Unions in Birmingham, Alabama, 1897-1904.” Labor History 10 (Summer 1969): 375-407.