George C. Wallace (1963-67, 1971-79, 1983-87)

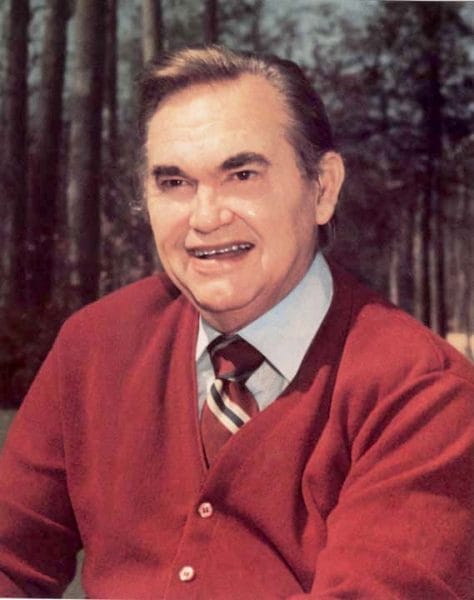

George C. Wallace

Between 1963 and 1987, George Wallace (1919-1998) held a virtual monopoly on the governor‘s office in Alabama, a position from which he promoted low-grade industrial development, low taxes, and trade schools as the keys to the state’s future. He was elected governor for an unprecedented four terms in 1962, 1970, 1974, and 1982, and was de facto governor during the administration of his first wife, Lurleen Burns Wallace, from 1967 to 1968. Wallace also launched four unsuccessful bids for the presidency on platforms that opposed the expansion of federal power and appealed to white populist sentiments. During each election cycle, he modified his racial views to suit the times. Despite his support for road construction, education, and industrial development, Wallace is widely known for his resistance to civil rights, limited economic vision, failure to reform the tax code, and total focus on campaigning, at the expense of running the state.

George C. Wallace

Between 1963 and 1987, George Wallace (1919-1998) held a virtual monopoly on the governor‘s office in Alabama, a position from which he promoted low-grade industrial development, low taxes, and trade schools as the keys to the state’s future. He was elected governor for an unprecedented four terms in 1962, 1970, 1974, and 1982, and was de facto governor during the administration of his first wife, Lurleen Burns Wallace, from 1967 to 1968. Wallace also launched four unsuccessful bids for the presidency on platforms that opposed the expansion of federal power and appealed to white populist sentiments. During each election cycle, he modified his racial views to suit the times. Despite his support for road construction, education, and industrial development, Wallace is widely known for his resistance to civil rights, limited economic vision, failure to reform the tax code, and total focus on campaigning, at the expense of running the state.

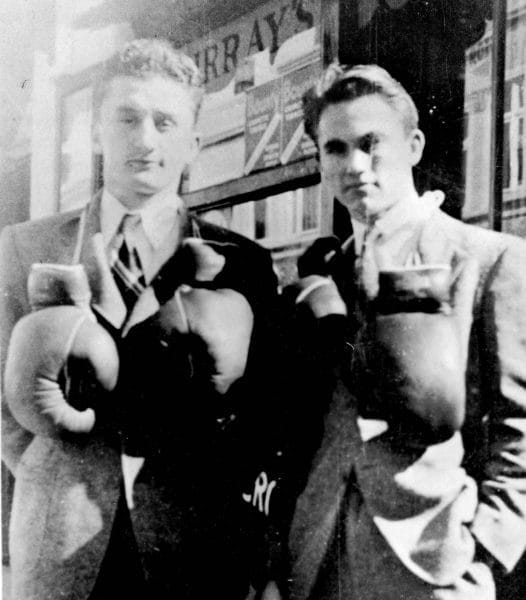

George Wallace and Boxing Partner

Born in the railroad town of Clio on August 25, 1919, to George C. Wallace and Mozelle Smith, George Corley Wallace Jr. grew up in Barbour County, where his father and his grandfather participated in local politics at the courthouse in Clayton. He was the eldest of two brothers and a sister. His brother Jack Wilfred Wallace became a circuit court judge and would administer the oath of office to George for all four of his inaugurations as governor. He attended and graduated from Barbour County High School in 1937. Having watched politicians “work” the crowds at social events, young George embarked on his own political career when he won a position as a page in the state Senate in 1935 and spent that summer in Montgomery meeting lawmakers. Too small for football, Wallace boxed, winning the 1936 and 1937 Alabama Golden Gloves championships. Between 1937 and 1942, he attended the University of Alabama, in Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, where he met several fellow students destined to cross his political path, including future federal judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. and future staff members Glen Curlee and Bill Jones. Wallace earned his law degree in 1942 and volunteered for the army, as the United States was involved in World War II. Before his induction, he assisted the gubernatorial campaign of Chauncey Sparks, state representative of Barbour County, who guaranteed the young man a job after the war. Also that summer, Wallace courted Lurleen Burns, a 16-year-old sales clerk, whom he married on May 21, 1943.

George Wallace and Boxing Partner

Born in the railroad town of Clio on August 25, 1919, to George C. Wallace and Mozelle Smith, George Corley Wallace Jr. grew up in Barbour County, where his father and his grandfather participated in local politics at the courthouse in Clayton. He was the eldest of two brothers and a sister. His brother Jack Wilfred Wallace became a circuit court judge and would administer the oath of office to George for all four of his inaugurations as governor. He attended and graduated from Barbour County High School in 1937. Having watched politicians “work” the crowds at social events, young George embarked on his own political career when he won a position as a page in the state Senate in 1935 and spent that summer in Montgomery meeting lawmakers. Too small for football, Wallace boxed, winning the 1936 and 1937 Alabama Golden Gloves championships. Between 1937 and 1942, he attended the University of Alabama, in Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, where he met several fellow students destined to cross his political path, including future federal judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. and future staff members Glen Curlee and Bill Jones. Wallace earned his law degree in 1942 and volunteered for the army, as the United States was involved in World War II. Before his induction, he assisted the gubernatorial campaign of Chauncey Sparks, state representative of Barbour County, who guaranteed the young man a job after the war. Also that summer, Wallace courted Lurleen Burns, a 16-year-old sales clerk, whom he married on May 21, 1943.

During Army Air Force basic training, Wallace contracted spinal meningitis, which ended his chances of piloting a plane. The Army taught Wallace the mechanics of B-29 bombers and commissioned him a sergeant. He served under the command of Gen. Curtis LeMay in the 58th Wing of the Twentieth Air Force, which in the summer of 1945 bombed Japan. He trained in Alamogordo, New Mexico, and flew with nine missions from the base on the island of Tinian in the Marianas.

Early Political Career

Returning to Alabama at the war’s end, Wallace asked Governor Sparks for the promised job. For several months, he worked as an assistant attorney general until taking a leave of absence to run for a seat in the state legislature representing Barbour County. Wallace’s victory in the spring 1946 Democratic primary secured his election in the fall. During his two terms in the Alabama legislature, from 1947 to 1953, Wallace wrote legislation promoting trade schools and industrial development to attract manufacturing jobs for rural white voters. He co-sponsored the Trade School Act of 1947, which taxed liquor to build vocational schools, and in 1951, helped push through the Wallace-Cater Acts, which attracted multinational corporations with offers of readily available, poorly educated non-union white workers for hire at below national wages.

Wallace appeared to support the reformist administration of Gov. James E. “Big Jim” Folsom. But he never endorsed Folsom’s efforts to reform the state government through reapportioning the legislature, expanding black suffrage, reforming the tax code, and increasing social spending. Wallace instead supported the Black Belt-Big Mule alliance of plantation owners and industrialists who had dominated state politics since Reconstruction by defending white supremacy, controlling the legislature, and promoting a colonial economy whereby corporations extracted the state’s raw wealth in a system that limited development and added value to manufacturing communities outside its borders. Nonetheless, as delegates to the Democratic National Convention in 1948, both Folsom and Wallace refused to join other southerners in leaving the convention over the party’s civil rights platform.

After six years in the legislature, Wallace announced his candidacy for circuit judge of the state’s Third Judicial District. Campaigning against Preston Clayton—a wealthy, former anti-Folsom state senator and Army lieutenant colonel—Wallace explained at rallies that officers should vote for his opponent but, “All you privates vote for me.” Wallace’s pseudo-populist rhetoric and sharp retorts soon became his political hallmarks. With a steady income, Wallace bought a house in Clayton for his family, which by this time included Bobbi Jo, born in 1945, Peggy Sue, born in 1950, and George Jr., born in 1951. Wallace’s constant campaigning over the years, however, essentially made him an absentee father. He directed Folsom’s south Alabama reelection campaign in 1954, taking that opportunity to learn political ploys from a master showman and to build his own political base.

Rise of Racial Politics

Wallace Campaign Speech, 1958

Folsom’s mild response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which repudiated the separate but equal doctrine, led Wallace to disagree with the governor over the issue of segregation and decide to seek the office himself in 1958. Thirteen candidates ran in the May 1958 Democratic primary, with Attorney General John Patterson being the most formidable. After denouncing Patterson’s ties to the Ku Klux Klan, Wallace received the unwanted endorsement of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), an outcome that contributed to his sound defeat in the primary and led him to appeal to segregationist sentiments in Alabama.

Wallace Campaign Speech, 1958

Folsom’s mild response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which repudiated the separate but equal doctrine, led Wallace to disagree with the governor over the issue of segregation and decide to seek the office himself in 1958. Thirteen candidates ran in the May 1958 Democratic primary, with Attorney General John Patterson being the most formidable. After denouncing Patterson’s ties to the Ku Klux Klan, Wallace received the unwanted endorsement of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), an outcome that contributed to his sound defeat in the primary and led him to appeal to segregationist sentiments in Alabama.

Wallace returned to the circuit court bench, where he developed a strategy of opposing the federal government in staged showdowns over civil rights for political gain. When the U.S. Civil Rights Commission requested Barbour County and Bullock County voting records, Wallace took them from the grand juries for alleged safekeeping and refused to release them to federal agents, threatening to “lock up” anyone who tried to take them. Federal District judge Frank Johnson cited Wallace with contempt of court for hindering the work of the commission. Faced with jail, Wallace met with Johnson and privately agreed to return the records to the grand juries so they could give them to the commission. Then Wallace proclaimed publicly that he had “stood up” to the federal government by not personally handing over the records. This empty but symbolic gesture appealed to many Alabama voters, who saw meaning in the resistance to federal encroachment.

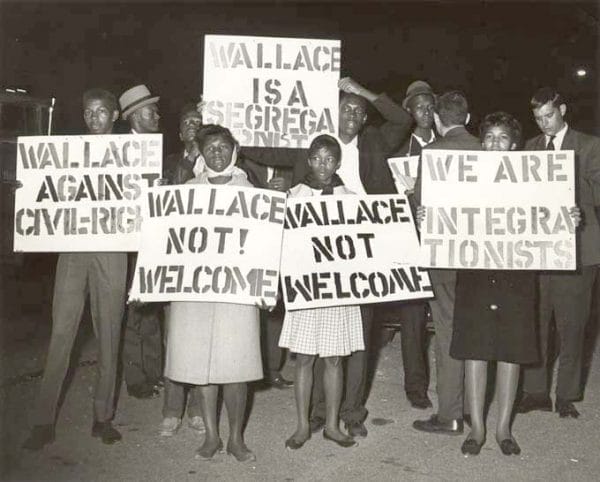

Wallace Protestors, ca. 1964

Against the backdrop of civil rights protests and federal court orders and after the birth of his fourth child, Janie Lee, Wallace organized his 1962 gubernatorial campaign around increasingly ugly rhetoric. He denounced Judge Johnson and threatened to “stand in the schoolhouse door” to defy federal court orders on desegregation. Wallace won the primary with the largest number of votes ever received by a gubernatorial candidate to that time and then won the general election.

Wallace Protestors, ca. 1964

Against the backdrop of civil rights protests and federal court orders and after the birth of his fourth child, Janie Lee, Wallace organized his 1962 gubernatorial campaign around increasingly ugly rhetoric. He denounced Judge Johnson and threatened to “stand in the schoolhouse door” to defy federal court orders on desegregation. Wallace won the primary with the largest number of votes ever received by a gubernatorial candidate to that time and then won the general election.

Because of his appeal to common white people, journalists incorrectly described Wallace as a populist, suggesting he shared characteristics with earlier politicians who had advocated biracial politics to achieve reform. Rather, Wallace used white supremacy to resist reapportionment and defend Alabama’s unfair tax structure. Wallace recognized the demise of the cotton economy and championed its replacement with industry, all the while defending the status quo. Yet his support for increased state spending for education, road construction, and public health to win votes assisted average black and white citizens and marked him as a “liberal.”

Patronage Politics

Wallace Family in the Mid-1960s

During his first term (1963-1967), Wallace attracted nearly $350 million in expanded and new industries to Alabama, which added 19,000 low-wage jobs in 1963 alone. Teachers received a substantial raise, and the state provided free textbooks to high schools, for which Wallace was praised by many members of the Alabama Education Association (AEA). Also, he sold $116 million in state bonds for Alabama’s colleges and universities and rarely meddled in the administrative matters of higher education. Yet Wallace never identified a stable funding source for public education. He found new money by increasing the state’s sales tax from $0.03 to $0.04, raising the state’s bonded indebtedness, and depending on increased revenues from expansion of the state’s industrial base.

Wallace Family in the Mid-1960s

During his first term (1963-1967), Wallace attracted nearly $350 million in expanded and new industries to Alabama, which added 19,000 low-wage jobs in 1963 alone. Teachers received a substantial raise, and the state provided free textbooks to high schools, for which Wallace was praised by many members of the Alabama Education Association (AEA). Also, he sold $116 million in state bonds for Alabama’s colleges and universities and rarely meddled in the administrative matters of higher education. Yet Wallace never identified a stable funding source for public education. He found new money by increasing the state’s sales tax from $0.03 to $0.04, raising the state’s bonded indebtedness, and depending on increased revenues from expansion of the state’s industrial base.

Because he enjoyed campaigning more than governing, Wallace frequently relied on political appointees, many of whom used their positions for personal gain. Graft abounded as friends won lucrative state contracts and bought state surplus at discount while making large political donations to Wallace’s numerous campaigns. He established technical and junior colleges as political favors. To the 12 schools that existed in 1962, Wallace and the legislature added 20 more, each one in the hometown of a state board of education member. Wallace used federal funds to pave roads through rural areas but refused to build interstates in or around Birmingham because most voters there supported his opponents.

Confronting Washington, Presidential Aspirations

Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

The Wallace administration intervened in civil rights conflicts and heightened racial tensions that led to violence and death. The governor turned the Alabama State Patrol into the State Troopers, outfitting the white-only force in uniforms with Confederate flag patches, steel helmets, and carbines. Under the command of Col. Al Lingo, state troopers intervened in community crises such as the Birmingham demonstrations of 1963. Wallace also created the unconstitutional Sovereignty Commission to spy on Alabamians who advocated race reforms. When the federal courts ordered the desegregation of the University of Alabama in June 1963, he concocted an elaborate charade that appeared to fulfill his campaign promise to stand in the schoolhouse door to block African American students from entering. After Pres. John F. Kennedy federalized the state troopers to force the registration of two black students, Wallace stepped aside. Yet this hollow act won him support across America. To hamper federal court orders desegregating Alabama’s public schools, Wallace sent Lingo and the state troopers to harass students in Mobile and Tuskegee. The hostile racial climate encouraged Ku Klux Klansmen to bomb the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killing four black girls, after which the Wallace administration resisted efforts to bring the perpetrators to justice. During the voting rights campaign in March 1965, Wallace ordered Lingo’s troopers to assist Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark, whose forces responded to a civil rights demonstration with brutality at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge on “Bloody Sunday.” Wallace’s advocacy of violence prompted passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which fundamentally altered Alabama’s electorate by adding thousands of black voters to the rolls. So rather than maintain segregation, his defiance hastened its demise.

Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

The Wallace administration intervened in civil rights conflicts and heightened racial tensions that led to violence and death. The governor turned the Alabama State Patrol into the State Troopers, outfitting the white-only force in uniforms with Confederate flag patches, steel helmets, and carbines. Under the command of Col. Al Lingo, state troopers intervened in community crises such as the Birmingham demonstrations of 1963. Wallace also created the unconstitutional Sovereignty Commission to spy on Alabamians who advocated race reforms. When the federal courts ordered the desegregation of the University of Alabama in June 1963, he concocted an elaborate charade that appeared to fulfill his campaign promise to stand in the schoolhouse door to block African American students from entering. After Pres. John F. Kennedy federalized the state troopers to force the registration of two black students, Wallace stepped aside. Yet this hollow act won him support across America. To hamper federal court orders desegregating Alabama’s public schools, Wallace sent Lingo and the state troopers to harass students in Mobile and Tuskegee. The hostile racial climate encouraged Ku Klux Klansmen to bomb the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killing four black girls, after which the Wallace administration resisted efforts to bring the perpetrators to justice. During the voting rights campaign in March 1965, Wallace ordered Lingo’s troopers to assist Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark, whose forces responded to a civil rights demonstration with brutality at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge on “Bloody Sunday.” Wallace’s advocacy of violence prompted passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which fundamentally altered Alabama’s electorate by adding thousands of black voters to the rolls. So rather than maintain segregation, his defiance hastened its demise.

Through his divisive actions, Wallace won a national following that convinced him to seek the 1964 Democratic Party nomination for president. He redefined his main issue as not race but the rise of an all-powerful central government. Wallace exceeded his expectations and seemed on the verge of victory when he polled 43 percent in Maryland and carried one-third of the votes in both the Indiana and Wisconsin primaries. With no chance to defeat incumbent Lyndon Johnson, however, Wallace ultimately backed out of the 1964 race and began making plans for 1968.

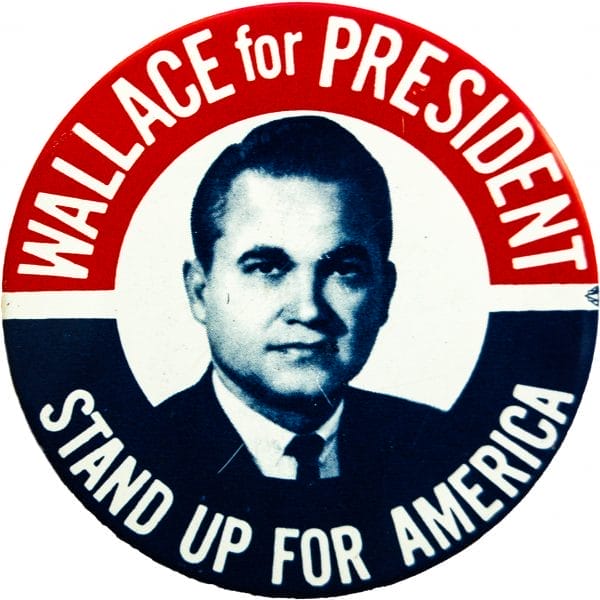

Wallace Campaign Button

Wallace needed to remain in the governor’s office to support his campaign. After his attempt to amend the 1901 Constitution to allow him to serve a second consecutive term failed to pass the legislature, Wallace decided to enter Lurleen as a candidate. Despite a prior diagnosis of cancer and the removal of a malignant tumor, Lurleen agreed to run for governor in 1966. Telling folks to “stand up for Alabama,” she made a few prepared remarks at campaign stops before giving way to her husband. Winning in a landslide, Lurleen Wallace made George her “chief advisor” and set him up in an office across from hers in the capitol. She served just over a year before cancer claimed her life on May 7, 1968. All the while, Wallace campaigned for president as an independent, organizing his new campaign around a platform that promoted “law and order.” Mocking antiwar demonstrators and ridiculing people who “dropped out” of the American economic system, Wallace’s flag-waving, pro-middle-class rhetoric endeared him to most working-class and middle-class people who saw the youth rebellions of the 1960s as tearing the nation apart. The Citizens Council, John Birch Society, and other conservative groups joined blue-collar whites in financing the American Independent Party. Despite Democrat Hubert Humphrey’s appeal to newly registered black voters and Republican Richard Nixon’s “southern strategy” to attract white suburbanites, polls found Wallace with 20 to 25 percent of the national vote in September 1968, a strong enough showing to suggest his candidacy might throw the election into the House of Representatives if there was no clear winner in the Electoral College.

Wallace Campaign Button

Wallace needed to remain in the governor’s office to support his campaign. After his attempt to amend the 1901 Constitution to allow him to serve a second consecutive term failed to pass the legislature, Wallace decided to enter Lurleen as a candidate. Despite a prior diagnosis of cancer and the removal of a malignant tumor, Lurleen agreed to run for governor in 1966. Telling folks to “stand up for Alabama,” she made a few prepared remarks at campaign stops before giving way to her husband. Winning in a landslide, Lurleen Wallace made George her “chief advisor” and set him up in an office across from hers in the capitol. She served just over a year before cancer claimed her life on May 7, 1968. All the while, Wallace campaigned for president as an independent, organizing his new campaign around a platform that promoted “law and order.” Mocking antiwar demonstrators and ridiculing people who “dropped out” of the American economic system, Wallace’s flag-waving, pro-middle-class rhetoric endeared him to most working-class and middle-class people who saw the youth rebellions of the 1960s as tearing the nation apart. The Citizens Council, John Birch Society, and other conservative groups joined blue-collar whites in financing the American Independent Party. Despite Democrat Hubert Humphrey’s appeal to newly registered black voters and Republican Richard Nixon’s “southern strategy” to attract white suburbanites, polls found Wallace with 20 to 25 percent of the national vote in September 1968, a strong enough showing to suggest his candidacy might throw the election into the House of Representatives if there was no clear winner in the Electoral College.

At the height of his popularity, Wallace’s extremism and his poor choice of a running mate wrecked his chances. His vice-presidential choice, Gen. Curtis LeMay, informed reporters he would use nuclear weapons in Vietnam to win the war. The media lampooned the reactionary policies, yet Wallace won in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi, receiving 46 electoral votes—short of what he needed to disrupt Nixon’s victory.

Second Term as Governor

George and Cornelia Wallace

Wallace eyed the 1970 governor’s race as an avenue to the presidency in 1972. After pledging to support Gov. Albert Brewer, he announced his own candidacy. Brewer, a racial moderate favored by progressives, positioned himself as Alabama’s “full-time governor.” He polled a plurality in the primary, forcing a runoff with Wallace. Running the dirtiest gubernatorial campaign in Alabama’s history, Wallace implied that Brewer was homosexual and his wife was an alcoholic, while his partisans circulated overtly racist campaign literature. Brewer, who ran a clean campaign, lost to Wallace by 34,000 votes. In 1971, Wallace married Cornelia Ellis Snively, niece of Big Jim Folsom whom he first met in 1947, when she was living in the governor’s mansion.

George and Cornelia Wallace

Wallace eyed the 1970 governor’s race as an avenue to the presidency in 1972. After pledging to support Gov. Albert Brewer, he announced his own candidacy. Brewer, a racial moderate favored by progressives, positioned himself as Alabama’s “full-time governor.” He polled a plurality in the primary, forcing a runoff with Wallace. Running the dirtiest gubernatorial campaign in Alabama’s history, Wallace implied that Brewer was homosexual and his wife was an alcoholic, while his partisans circulated overtly racist campaign literature. Brewer, who ran a clean campaign, lost to Wallace by 34,000 votes. In 1971, Wallace married Cornelia Ellis Snively, niece of Big Jim Folsom whom he first met in 1947, when she was living in the governor’s mansion.

During his second term, from 1971 to 1975, Wallace shifted his opposition to the U.S. Supreme Court’s April 1971 ruling in support of court-ordered busing to achieve racially mixed schools as another example of “unconstitutional” federal involvement in state affairs. Despite initial resistance from the legislature, Wallace passed a budget that established the Alabama Office of Consumer Protection and increased both retirement pensions and unemployment compensation. In 1973-74, he won legislative approval of a record educational appropriation and continued his first term’s energetic pursuit of new businesses for the state. Nonetheless, the governor showed little interest in daily details, leaving them in the hands of cabinet members.

George Wallace on Stage with Richard Nixon

As the 1972 presidential election approached, Pres. Richard Nixon began encouraging the Justice Department to prosecute Wallace’s brother Gerald on charges that he rigged state bidding procedures, solicited and received illegal campaign contributions, and accepted kickbacks. The Internal Revenue Service expanded the investigation to include Wallace advisor Seymore Trammell. After George announced that he might seek the Democratic Party nomination in 1972, rather than run on the American Independent Party ticket, the Justice Department dropped its investigation of the Wallaces, but Trammell was convicted and jailed. In the Democratic primary, Wallace wreaked more havoc than he had as an independent in 1968. Candidates of both parties echoed Wallace’s anti-government rhetoric, and both parties became more conservative, a shift that would set their agendas for decades.

George Wallace on Stage with Richard Nixon

As the 1972 presidential election approached, Pres. Richard Nixon began encouraging the Justice Department to prosecute Wallace’s brother Gerald on charges that he rigged state bidding procedures, solicited and received illegal campaign contributions, and accepted kickbacks. The Internal Revenue Service expanded the investigation to include Wallace advisor Seymore Trammell. After George announced that he might seek the Democratic Party nomination in 1972, rather than run on the American Independent Party ticket, the Justice Department dropped its investigation of the Wallaces, but Trammell was convicted and jailed. In the Democratic primary, Wallace wreaked more havoc than he had as an independent in 1968. Candidates of both parties echoed Wallace’s anti-government rhetoric, and both parties became more conservative, a shift that would set their agendas for decades.

At a political rally on May 15, 1972, in a strip-mall parking lot in Laurel, Maryland, would-be assassin Arthur Bremer fired five shots into Wallace. The assassination attempt left him paralyzed below the waist and in constant pain for the rest of his life. The next day, Wallace won 39 percent of the vote in Maryland and 51 percent of the vote in Michigan, as conservative Democrats registered their opposition to busing and concerns over crime. Released from the hospital to attend the Democratic National Convention in July 1972, a wheelchair-bound Wallace received an ovation when he addressed the delegates.

While he sought treatment for the paralysis and complications from the shooting, Wallace suffered deep depressions and became a born-again Christian. But his prior good health, a strict regimen of physical therapy, and the belief that others considered him washed up politically brought him back fighting. A year after the assassination attempt, he stood strapped to a podium and addressed the Alabama legislature on local issues. The amazing and emotional event secured his political comeback. Further, Wallace renounced racism, claiming he only opposed a “central government meddling in local affairs.” To symbolize the change, he returned to Tuscaloosa to crown the first black homecoming queen at the University of Alabama. He ran for re-election as governor in 1974 by opposing the federal bureaucracy and secured victory by distributing plenty of political favors, especially in black neighborhoods, which saw an increase in paved roads and other public services. A quarter of all black voters cast ballots for Wallace, who won 65 percent of the vote, the largest margin ever posted in a primary.

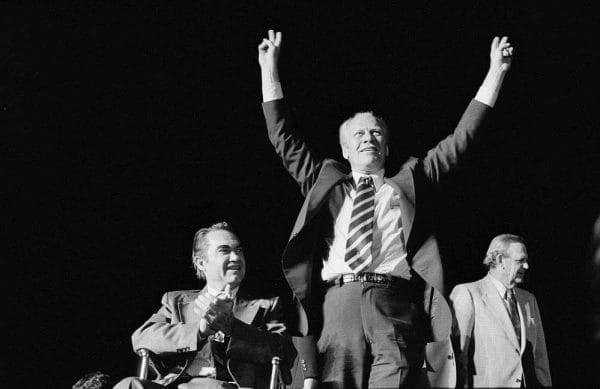

George Wallace and Gerald Ford

In his third term, from 1975-79, Wallace continued to ignore Alabama’s chronic problem of underfunding government programs. Although various commissions recommended raising property taxes, Wallace resisted this solution and adopted stop-gap measures that postponed the problems. Federal court rulings also plagued the Wallace administration. In 1971, Judge Johnson ordered the state to provide effective treatment to the patients in Alabama’s mental health facilities. In 1976, he declared that Alabama’s prison system constituted “cruel and unusual punishment” and ordered expensive remedial measures. Recalling earlier campaigns, Wallace denounced his old antagonist.

George Wallace and Gerald Ford

In his third term, from 1975-79, Wallace continued to ignore Alabama’s chronic problem of underfunding government programs. Although various commissions recommended raising property taxes, Wallace resisted this solution and adopted stop-gap measures that postponed the problems. Federal court rulings also plagued the Wallace administration. In 1971, Judge Johnson ordered the state to provide effective treatment to the patients in Alabama’s mental health facilities. In 1976, he declared that Alabama’s prison system constituted “cruel and unusual punishment” and ordered expensive remedial measures. Recalling earlier campaigns, Wallace denounced his old antagonist.

Last Runs

Wallace made a final bid for the presidency in 1976. Concerned about his health, voters supported another southerner and Washington outsider, Jimmy Carter, during the Democratic primaries. Responding to his poor showing, the Alabama governor endorsed the former Georgia governor. At about the same time, Wallace divorced his wife Cornelia after a bitter public dispute. He remarried in 1981 to 33-year-old Lisa Taylor, the daughter of a coal baron who, with her sister, had formed the Mona and Lisa duo that had entertained crowds during his 1968 presidential race. Then Wallace hit the campaign trail for an unprecedented fourth term as governor.

Wallace Official Portrait, 1983

In 1982, black voters helped reelect Wallace, giving him one-third of their votes in the first primary. He then increased this constituency to defeat then-Lt. Gov. George McMillan by one percentage point in the Democratic runoff. In the general election, Wallace carried 90 percent of the state’s black electorate, linking it with rural white voters and members of the Alabama Education Association to form a coalition that defeated his opponent, Republican Emory Folmar, mayor of Montgomery. Despite his declining health, the term would prove to be Wallace’s most productive. His administration negotiated an agreement among trial lawyers, unions, and business leaders over job-related injuries and workplace liability. The federal government recognized state improvements in mental hospitals and prisons. The creation of the Alabama Trust Fund, which made offshore leases on state oil and natural gas a funding source for education and other social spending, was perhaps his greatest legislative success. He continued to appeal to domestic and foreign corporations to relocate their businesses to Alabama to generate new manufacturing jobs. He appointed African Americans to advisory panels and increased funding for education. Yet Wallace’s attempt to revise Alabama’s tax structure failed.

Wallace Official Portrait, 1983

In 1982, black voters helped reelect Wallace, giving him one-third of their votes in the first primary. He then increased this constituency to defeat then-Lt. Gov. George McMillan by one percentage point in the Democratic runoff. In the general election, Wallace carried 90 percent of the state’s black electorate, linking it with rural white voters and members of the Alabama Education Association to form a coalition that defeated his opponent, Republican Emory Folmar, mayor of Montgomery. Despite his declining health, the term would prove to be Wallace’s most productive. His administration negotiated an agreement among trial lawyers, unions, and business leaders over job-related injuries and workplace liability. The federal government recognized state improvements in mental hospitals and prisons. The creation of the Alabama Trust Fund, which made offshore leases on state oil and natural gas a funding source for education and other social spending, was perhaps his greatest legislative success. He continued to appeal to domestic and foreign corporations to relocate their businesses to Alabama to generate new manufacturing jobs. He appointed African Americans to advisory panels and increased funding for education. Yet Wallace’s attempt to revise Alabama’s tax structure failed.

Wallace ended his fourth term with the desire to run again, but his advisors discouraged the notion. A month after leaving office in January 1987, George and his third wife divorced. He accepted a symbolic position at Troy State University and, over the next decade, promoted the political career of his son. After numerous hospitalizations, Wallace died in Montgomery on September 13, 1998. The state buried him in the capitol city’s Greenwood Cemetery.

Given his continuous campaigning, Wallace may have governed the least of any Alabama chief executive, but he was certainly the most significant of all. It was not because of any positive outcome, for he left the state with a manufacturing sector committed to low-skill, low-wage jobs, special interests controlling the legislature, and a tax code that favored large landholders and corporations. He entered office in an age of transition and, by defending segregation, forestalled the changes necessary to improve Alabama’s future. After fomenting a violent atmosphere, he became the victim of violence. Wallace recanted and sought the forgiveness of those he had wronged. Yet his reactionary message altered mainstream politics as both national parties adopted his antigovernment rhetoric. Certainly in Alabama, images of the racist Wallace continue to haunt the state.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Carroll, Peter N. Famous In America: Jane Fonda, George Wallace, Phyllis Schlafly, John Glenn: The Passion to Succeed. New York: E.P. Dutton. 1985.

- Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, The Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

- Frady, Marshall. Wallace. New York: World Publishing Company, 1968.

- Frederick, Jeff. Stand Up For Alabama: Governor George Wallace. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

- Lesher, Stephen. George Wallace: American Populist. Reading, Mass. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1994.

- Permaloff, Anne, and Carl Grafton. Political Power in Alabama: The More Things Change . . . . Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1995.