Vine and Olive Colony

Vine and Olive Colony

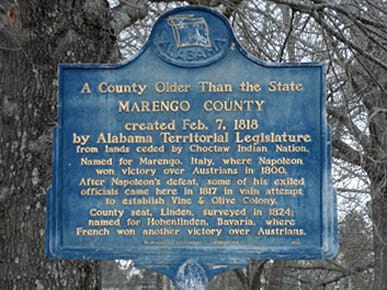

The Vine and Olive Colony was an early settlement of French expatriates located near present-day Demopolis, in Marengo County. The settlers were mythologized as noble heroes of the Napoleonic wars in Albert James Pickett‘s 1851 history of Alabama’s beginnings, but their story is somewhat less romantic. In fact, none of the colonists were of noble birth, and the plan by which they were to establish orchards of grapes and olives in western Alabama was ill-conceived at best. Although the Vine and Olive Colony can be described as a failure, many of the French colonists who remained successfully integrated into the plantation-agriculture system of their American neighbors. Today, the myth of the Vine and Olive Colony remains an important facet of Marengo County folklore.

Vine and Olive Colony

The Vine and Olive Colony was an early settlement of French expatriates located near present-day Demopolis, in Marengo County. The settlers were mythologized as noble heroes of the Napoleonic wars in Albert James Pickett‘s 1851 history of Alabama’s beginnings, but their story is somewhat less romantic. In fact, none of the colonists were of noble birth, and the plan by which they were to establish orchards of grapes and olives in western Alabama was ill-conceived at best. Although the Vine and Olive Colony can be described as a failure, many of the French colonists who remained successfully integrated into the plantation-agriculture system of their American neighbors. Today, the myth of the Vine and Olive Colony remains an important facet of Marengo County folklore.

The romantic version of the Vine and Olive Colony is based in American mythology about the frontier and the “can-do” spirit of the pioneers. According to folklore, in 1817 exiled French military aristocrats loyal to the recently-deposed Emperor Napoleon founded the Vine and Olive Colony at the confluence of the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers. The settlement was so named because the immigrants had been granted the lands by the U.S. Congress under the condition that they plant them with grape vines and olive trees. The French set about their task enthusiastically albeit with little or no agricultural competence. Thus, their settlement in Marengo County was only briefly an oasis of sophistication on the frontier. But, more comfortable in a battle or ballroom than behind a plow, they soon faltered. The wilderness eventually broke their will, and they returned to France, leaving their lands to sturdy American pioneers. Subsequent retellings have added new details but have not changed the story’s main themes.

Very little of this traditional account of the Vine and Olive Colony, in fact, is accurate. Only one “aristocrat”—Gen. Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes—settled there, and he was actually the son of a merchant. No nobles and only a few other officers settled in the colony, and they all left Alabama after short stays. By 1830, not a single Napoleonic veteran was left. In reality, the majority of the French colonists were neither soldiers nor even from France itself. Most were middle-class white refugees of the Haitian slave rebellion of 1791. Many fled to the United States and settled in New Orleans and Philadelphia. The settlers of the Vine and Olive Colony originated in the refugee community of the latter city.

The idea of a French settlement in the “Old Southwest” (now the central southeastern states) was broached in 1816 by Jean-Simon Chaudron, editor of Philadelphia’s leading French newspaper, the Abeille Américaine (The American Bee). Chaudron used his newspaper to promote the project. By November, a group of merchants and military figures from Santo Domingo had formed the Colonial Society (later renamed the Society for the Cultivation of the Vine and Olive), with Lefebvre-Desnouettes as its president, and had dispatched scouts to the Ohio Valley and beyond to locate a suitable site. Its vice president, former U.S. Consul to Bordeaux William Lee, lobbied Congress to support the project. Congress took an interest in the plan because such a colony would consolidate the American hold on the Gulf Coast and because most members of the American political elite had a great deal of sympathy for the French exiles, whom they saw as fellow Republicans oppressed by a monarchy. They were also attracted to the prospect of establishing a domestic winemaking industry that would free the United States from dependence on imported European wines.

Vine and Olive Colony

Both initiatives succeeded. In January 1817, the society had selected a settlement location on the Tombigbee River on former Choctaw lands. At the same time, Lee won the support of key politicians, including Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. On March 3, 1817, Congress passed an act “disposing of a tract of land to embrace four townships, on favorable terms to the emigrants, to enable them successfully to introduce the cultivation of the vine and olive.” It granted them 92,000 acres of land near the present site of Demopolis and gave them a 14-year grace period before they had to plant a “reasonable” proportion of the land in grapes and olives and before they had to pay for their land (at a mere $2.00 per acre). In spring 1817, an advance party of about 40 settlers sailed from Philadelphia to Mobile and then up the Tombigbee River to the grant. They reported favorably about conditions on the grant. Encouraged, Lefebvre-Desnouettes decided to lead a larger party to Alabama, and they sailed from Philadelphia to Mobile on August 1817.

Vine and Olive Colony

Both initiatives succeeded. In January 1817, the society had selected a settlement location on the Tombigbee River on former Choctaw lands. At the same time, Lee won the support of key politicians, including Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. On March 3, 1817, Congress passed an act “disposing of a tract of land to embrace four townships, on favorable terms to the emigrants, to enable them successfully to introduce the cultivation of the vine and olive.” It granted them 92,000 acres of land near the present site of Demopolis and gave them a 14-year grace period before they had to plant a “reasonable” proportion of the land in grapes and olives and before they had to pay for their land (at a mere $2.00 per acre). In spring 1817, an advance party of about 40 settlers sailed from Philadelphia to Mobile and then up the Tombigbee River to the grant. They reported favorably about conditions on the grant. Encouraged, Lefebvre-Desnouettes decided to lead a larger party to Alabama, and they sailed from Philadelphia to Mobile on August 1817.

The colony seemed to be developing as planned, but none of the land had been allotted to individual settlers prior to their departure. This task fell to Gen. Charles Lallemand, who had replaced Lefebvre-Desnouettes as president of the Colonial Society. Lallemand had joined the French army as a teenager in 1791 and was not disposed to give up the life of adventure he had led since that time. After Napoleon’s fall in 1815, he saw opportunity to revive his fortunes in the turbulent state of American affairs—then dominated by the wars of Latin American independence. During the fall of 1817, he secretly organized an expedition to invade Texas, whose ownership was disputed by Spain and the United States. This required funds that Lallemand determined to acquire by selling Vine and Olive Colony lands to speculators. He struck a deal with a group of mainly French merchants prominent in the Colonial Society who agreed to elect Lallemand president in return for convincing his followers in the society to sell their lands to the merchants for only $1.00 per acre. The merchants would thus acquire thousands of acres of land, and Lallemand would gain the funds he needed. The plan was accomplished in early December when 60 Lallemand loyalists sold their shares, thus filling Lallemand’s war chest. The merchants, some of whom became prominent residents of the Vine and Olive Colony, acquired more than 11,000 acres of land. In December 1817, Lallemand launched his invasion of Texas. This action diverted most of the officers from the Vine and Olive Colony, led to the concentration of grant land in the hands of a few merchants, and cast suspicions of land speculation over the whole enterprise. As 1818 began, there were only 69 settlers in the colony.

Marengo County

Most of the 347 original grantees never came to Alabama. Most were immigrants from France and refugees from Haiti who were well-established in Philadelphia and other cities and uninterested in uprooting their comfortable existences for the dangers and hardships of frontier life. They soon sold their allotments to the same merchants that had purchased Lallemand’s allotments. A few additional settlers travelled independently to the grant during the early 1820s, but their numbers were never great. Ultimately, only about 150 of the original grantees, some with families and others on their own, ever visited the grant. Most sailed to Mobile and then continued upriver by barge, horseback, or on foot. The journey was long, uncomfortable, and perilous, marred by shipwreck, drowning, and disease. Several of the settlers were military officers, but most were refugees from the Haitian Revolution. For them, settlement in Alabama meant the possibility of achieving the opulent lifestyle of the wealthiest planters they had witnessed in the French Caribbean. Acquiring slaves was therefore an immediate priority. For example, the day she arrived at Mobile in December 1819, one colonist, Madame Victoire George, purchased an enslaved woman on credit and continued to seek slaves after she arrived at her allotment. The cost of slaves was but one of the heavy startup expenses facing the colonists. Until their lands were cleared and planted, they also had to purchase food shipped upriver from Mobile. Their efforts at self-sufficiency struggled against the elements. The 1818 cotton crop failed, the 1819 crop was damaged by frost, that of 1821 by flooding, and that of 1822 by a late summer storm. The settlers also had difficulty in building proper homes. Most built log cabins. One observer commented that, although exorbitantly expensive, the dwellings were of poor quality. After 10 years, the grant’s largest structure was a log cabin measuring 19 by 23 feet. In addition to these hardships, diseases such as yellow fever periodically ravaged the colony. By 1825, more than 20 of the grantees had died.

Marengo County

Most of the 347 original grantees never came to Alabama. Most were immigrants from France and refugees from Haiti who were well-established in Philadelphia and other cities and uninterested in uprooting their comfortable existences for the dangers and hardships of frontier life. They soon sold their allotments to the same merchants that had purchased Lallemand’s allotments. A few additional settlers travelled independently to the grant during the early 1820s, but their numbers were never great. Ultimately, only about 150 of the original grantees, some with families and others on their own, ever visited the grant. Most sailed to Mobile and then continued upriver by barge, horseback, or on foot. The journey was long, uncomfortable, and perilous, marred by shipwreck, drowning, and disease. Several of the settlers were military officers, but most were refugees from the Haitian Revolution. For them, settlement in Alabama meant the possibility of achieving the opulent lifestyle of the wealthiest planters they had witnessed in the French Caribbean. Acquiring slaves was therefore an immediate priority. For example, the day she arrived at Mobile in December 1819, one colonist, Madame Victoire George, purchased an enslaved woman on credit and continued to seek slaves after she arrived at her allotment. The cost of slaves was but one of the heavy startup expenses facing the colonists. Until their lands were cleared and planted, they also had to purchase food shipped upriver from Mobile. Their efforts at self-sufficiency struggled against the elements. The 1818 cotton crop failed, the 1819 crop was damaged by frost, that of 1821 by flooding, and that of 1822 by a late summer storm. The settlers also had difficulty in building proper homes. Most built log cabins. One observer commented that, although exorbitantly expensive, the dwellings were of poor quality. After 10 years, the grant’s largest structure was a log cabin measuring 19 by 23 feet. In addition to these hardships, diseases such as yellow fever periodically ravaged the colony. By 1825, more than 20 of the grantees had died.

The colonists’ efforts were further complicated by a surveying error. The first colonists had chosen the bluffs above the juncture of the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers as their town site and named it Demopolis (City of the People). But the official federal land survey of August 1818 revealed that Demopolis lay outside of the grant. The French had to abandon their riverside site and establish a new capitol inland, which they called Aigleville (Eagle City). The town never attracted many inhabitants, however, and even the settlers preferred the nearby settlements of Demopolis and Greensboro. (The Noel-Ramsey Home in Greensboro, completed in 1821, is one of the few surviving structures connected with the Vine and Olive Colony.)

Despite these obstacles, the colonists did attempt vine and olive cultivation. They imported grape vines and olive saplings from Europe, but many of the plants died en route. The grape varieties they planted were generally unsuited to the region, and olive cultivation failed miserably in the state’s hot, humid climate. The only crop that thrived was cotton, but the colonists feared that they would lose their lands if they did not fulfill the conditions of vine and olive cultivation set by the terms of their original allotment. Consequently, in 1827 the remaining French colonists, together with American newcomers, petitioned Congress to relax the terms of the grant. In 1831, Congress released the grantees from the obligation to grow grapes and olives and lowered the price of their lands from $2.00 to $1.25 per acre. By this time, there remained little of the distinctly French settlement: it had become a collection of cotton plantations, much like the surrounding areas.

By the 1830s, most of the original settlers had drifted into Gulf Coast towns such as New Orleans and Mobile. Others returned to Philadelphia or France, selling their lands to Americans. Others simply abandoned their land. Some French colonists stayed and prospered. Shared business interests and intermarriage had joined American and French groups into a mixed planter elite that gradually shed the trappings of French language and culture. Although little remains of the French presence, their descendants still cherish their unique heritage.

The popular account of the Vine and Olive Colony first outlined by Pickett was further developed during the second half of the nineteenth century at the same time as several other brief, highly romanticized accounts that aimed to redefine southern identity after the war. The mythology of the Vine and Olive Colony gained popularity among Alabamians after World War I in a series of articles and papers that revived Pickett’s version of the story, thus reinforcing the popular account. It is unclear exactly why this revival occurred. The emerging film industry helped to promote a romanticized view of the Old South, and the French were greatly admired for their efforts in World War I. Alabama’s centennial of statehood also provided an occasion for local historical societies to celebrate one of the most alluring episodes in Alabama’s past. Additionally, historian Marie Bankhead Owen, who replaced her husband, Thomas M. Owen, in 1920 as director of the state archives, probably also played a role in fostering the romanticized version of the Vine and Olive Colony. Owen viewed her role as a promoter of Alabama pride through its history and emphasized commemoration over critical analysis.

The colony has been featured in several works of fiction. In 1934, Carl Carmer featured the story of the colony in his novel Stars Fell on Alabama. Carmer brought together all of the popular beliefs of the origin of the settlement that make it such a potent myth-making tool: “Dressed in rich uniforms, they cleared wooded land, ditched it, plowed it. Their wives, delicate women still in Paris gowns, milked the cows, carried water to the men in the field, cooked meals over coals in the fireplace.” In 1937, Emma Gelders Sterne published her novel, Some Plant Olive Trees, a fictional and highly romantic account of the Vine and Olive Colony. These literary mentions were joined in 1949 by a version of the story in the Republic Pictures film The Fighting Kentuckian, an attempt to cash in on the popularity of romanticized southern themes fostered by Gone With the Wind. In the film version, star John Wayne plays a Kentucky rifleman returning home from the Battle of New Orleans who rides to the rescue of the French as he helps the uniformed Napoleonic officers fight off an attack by unscrupulous American land speculators. The Fighting Kentuckian represented the peak of American interest (as well as the lowest point of historical accuracy) in the story.

Further Reading

- Blaufarb, Rafe. Bonapartists in the Borderlands: French Exiles and Refugees on the Gulf Coast, 1815-1835. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.

- ———. “Notes and Documents: French Consular Reports on the Association of French Emigrants: The Organization of the Vine and Olive Colony.” Alabama Review 56 (April 2003): 104-24.

- Saugera, Eric. Reborn in America: French Exiles and Refugees in the United States and the Vine and Olive Adventure, 1815-1865. Translated by Madeleine Velguth. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2011.