Mansfield Tyler

Mansfield Tyler

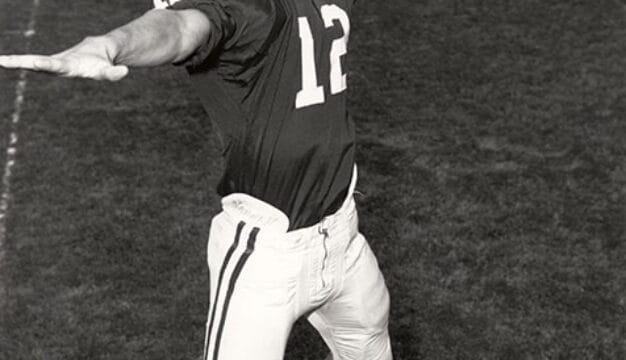

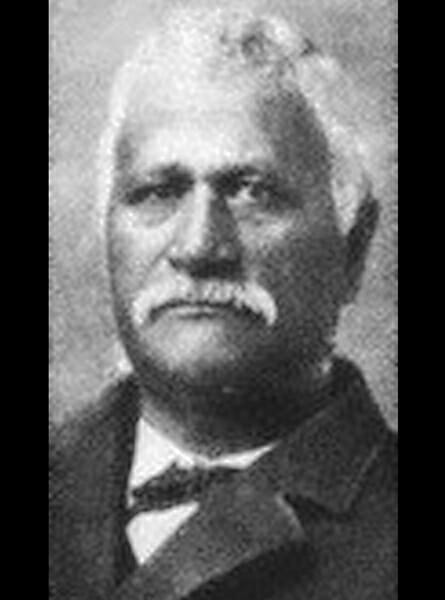

Born enslaved, Mansfield Tyler (1826-1904) rose to great prominence in many spheres in his adopted state of Alabama. He served a term in the Alabama House of Representatives and was chair of the Board of Trustees (1878 to 1904) of present-day Selma University, which he helped establish. Known locally as the “Baptist Pope of Lowndes County” for his influence and achievements as a minister, Tyler also founded churches and schools and led church associations and conventions.

Mansfield Tyler

Born enslaved, Mansfield Tyler (1826-1904) rose to great prominence in many spheres in his adopted state of Alabama. He served a term in the Alabama House of Representatives and was chair of the Board of Trustees (1878 to 1904) of present-day Selma University, which he helped establish. Known locally as the “Baptist Pope of Lowndes County” for his influence and achievements as a minister, Tyler also founded churches and schools and led church associations and conventions.

As is common with many enslaved peoples, very little is known about Tyler’s early life and upbringing. At some point he became the legal property of Rev. Jacob White, who lived about 12 miles from Augusta, Georgia. Tyler, though, was allowed to live with a great-aunt and her husband, Jacob Walker. Walker was pastor of the extant Springfield Baptist Church in Augusta, which claims to be the oldest African American church in the United States and had more than 1,000 African American parishioners at the time. It is possible that this is where Tyler learned to read and write.

At age 18, Tyler was taken to Alabama by his owner and at approximately age 20 became a Baptist preacher after feeling a religious calling. Tyler’s entry in the 1895 Cyclopedia of the Colored Baptists of Alabama says that he was a young man when he married his first wife, Phillis, and that she died 26 years later. Census records show that the couple had six children in Alabama: Mariah (1845), Millie (1848), Albert (1859), Felix (1862), Hannah (1865), and Robert (1868). Hannah apparently died in childhood, but the others graduated from Selma University, which their father played a critical role in founding. Felix practiced medicine in Lowndesboro and Robert was a pharmacist, both having graduated from Howard University in Washington, D.C. Albert was a schoolteacher in Birmingham. Mansfield’s daughters both married and remained in Alabama.

At some point after emancipation in 1865, Tyler moved to Lowndes County, where he joined the Lowndesboro Baptist Church. The church had been interracial for some years, but by 1867 its membership of 137 included only five white people, and the African American membership wanted to become a separate church. Church leaders ordained Tyler as a bishop and a separate board of deacons was established for the African American church at Lowndesboro. In her unpublished manuscript, Lowndesboro Baptist Church 1852-1988, local historian Flo Meadows notes that in August 1868, the Southern Aid Society of the United States, through the Freedman’s Bureau, contributed $150 to buy a building that had been built by Daniel Alexander and Mansfield Tyler as a school and church for the African American citizens of Lowndesboro. The congregants agreed to pay the balance on the building and lot, establishing the First Baptist Church of Lowndesboro, with a membership that grew to 327 by 1870.

The congregants selected Tyler and Alexander to represent the church at a convention in Montgomery on December 17, 1868, that organized the Alabama Colored Baptist State Convention (ACBSC). In 1869, Tyler founded another church in Lowndes County, First Baptist Church of White Hall. He remained diligent in pursuing new congregants, baptizing as many as 1,000 in Lowndesboro and 500 in White Hall during the course of his ministry.

Tyler married his second wife, Amanda Moore, on March 6, 1870. Also that year he was elected to serve as Lowndes County’s representative to the Alabama House of Representatives. During his two-year term, Tyler advocated for a strong public education system, land ownership for African American people, and universal suffrage, including women.

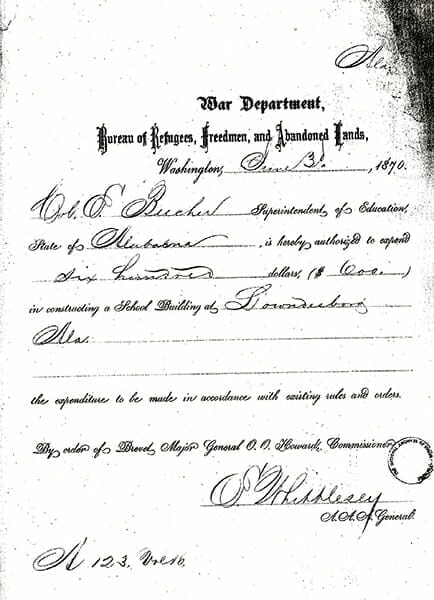

Lowndesboro School Funding Document

The Freedmen’s Bureau authorized the Alabama superintendent of education to spend $600 for the construction of a school building in “Lowndesborough,” in 1870. In 1871, Tyler bought land from a white family named Meadows. On this property he built a small church that year and later its larger replacement, the extant First Baptist Church of Lowndesboro, in 1880. In 1883, Tyler sold a portion of his property to the Lowndesboro Colored Education Association, an organization that had a ten-member board of trustees, including Tyler. Together they built the school for African American children, now known as the Lowndesboro School, most likely in 1883. The church building is one story with a gabled roof and a central steeple. The school is a one-story two-room structure with a gabled roof and pine board-and-batten construction. Both were added to National Register of Historic Places as contributing structures to the Lowndesboro Historic District in 2014. The school, which closed in 1967, was listed on the Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage in 2011.

Lowndesboro School Funding Document

The Freedmen’s Bureau authorized the Alabama superintendent of education to spend $600 for the construction of a school building in “Lowndesborough,” in 1870. In 1871, Tyler bought land from a white family named Meadows. On this property he built a small church that year and later its larger replacement, the extant First Baptist Church of Lowndesboro, in 1880. In 1883, Tyler sold a portion of his property to the Lowndesboro Colored Education Association, an organization that had a ten-member board of trustees, including Tyler. Together they built the school for African American children, now known as the Lowndesboro School, most likely in 1883. The church building is one story with a gabled roof and a central steeple. The school is a one-story two-room structure with a gabled roof and pine board-and-batten construction. Both were added to National Register of Historic Places as contributing structures to the Lowndesboro Historic District in 2014. The school, which closed in 1967, was listed on the Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage in 2011.

In 1873, Tyler was elected vice-president of ACBSC and in 1876 was elected president. Under his leadership, the ACBSC resolved to establish a theological school to educate young African American men in Alabama, with Tyler as chair of the Board of Trustees. Though white Baptists opposed the plan, Tyler and the other trustees approved the purchase of land and secured the site of the Old Fair Grounds in Selma, Dallas County, with a donation from white Baptists in northern states. The Alabama Baptist Normal and Theological School was established in 1878. Recognizing Tyler’s contributions to the school’s founding, the leadership established the Tyler Medal in 1880 and conferred a Doctor of Divinity degree on Tyler in 1890. The name was officially changed to Selma University around 1900, and Tyler served as chair of its Board of Trustees until his death in 1904.

Reflecting on Tyler’s life, historian Charles O. Boothe praised his financial support of worthy causes, his prowess as preacher, and his influence in Alabama. Tyler was honored as one of the “Reconstruction Period Black Members of the Alabama Legislature 1868-1879” in a marker erected on the Alabama State Capitol lawn in 2011 and in 2018 was inducted into the Alabama Men’s Hall of Fame. In July 2021, the National Park Service’s African American Civil Rights Grant Program awarded approximately $263,000 to the Elmore Bolling Foundation for the preservation and restoration of the Lowndesboro School. The foundation, which has owned the building since 2011, was assisted in securing the funds by Rep. Terri Sewell of Selma.

Additional Resources

Bailey, Richard. Neither Carpetbaggers Nor Scalawags: Black Officeholders During the Reconstruction of Alabama 1867-1878. Montgomery, Ala.: NewSouth Books, 2010.

Boothe, Charles Octavius. The Cyclopedia of the Colored Baptists of Alabama: Their Leaders and Their Work. Champaign, Ill.: Sports Publishing, 2004.

Fallin, Wilson. Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2007.