Coal Mining

Experiencing both boom and bust, the coal-mining industry has affected the lives of thousands of people in northern and central Alabama. The industry changed the face of the state—geographically, economically, socially, politically, culturally. Largely obscured today by reclamation projects, pine trees, and kudzu, the mining districts of Alabama are the remnants of an industrial boom that vastly expanded the state’s economy beyond its traditional agricultural base and shifted the political center away from its heart in the Black Belt.

The discovery of coal along Alabama’s rivers can be traced back to 1815, when several veterans of the Battle of New Orleans made their way into present-day central Alabama. One group of early settlers, led by Maj. Jonathan Mahan, found a Creek Indian village at the confluence of three creeks. Two-thirds of the party settled in the town and married Creek women; six others continued northward but returned later to stake their land claims and to create the settlement of Brierfield. Later, the Mahan family convinced ironmaster Jonathan Ware to build a forge along the waterway that they dubbed Mahan Creek. Descendant Adelaide Mahan (1872-1959) would gain renown as a painter.

Another account credits the initial discovery of coal to two young boys on a hunting expedition. Reportedly, Jonathan Newton Smith and Pleasant Fancher were camping near the Big Cahaba River in the early 1820s. They built a firepit of stones, cooked supper, and then drifted off to sleep. Smith later awakened to find the “stones” on fire. Frightened, the boys raced home in the dark, but later realized that they must have inadvertently used lumps of coal. The stream that flowed into Dailey’s Creek became known as Coal Branch. To the north, Levi Reid and James Grindle settled at the Locust Fork of the Warrior River, where they found plentiful coal deposits.

Early Coal Mining Efforts

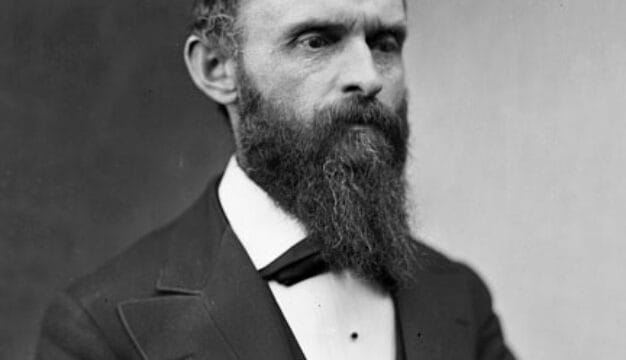

William Phineas Browne

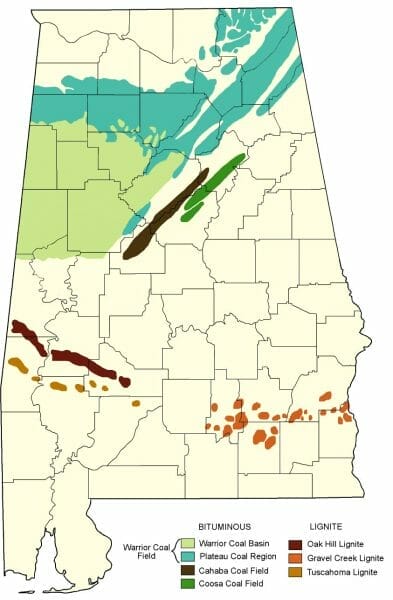

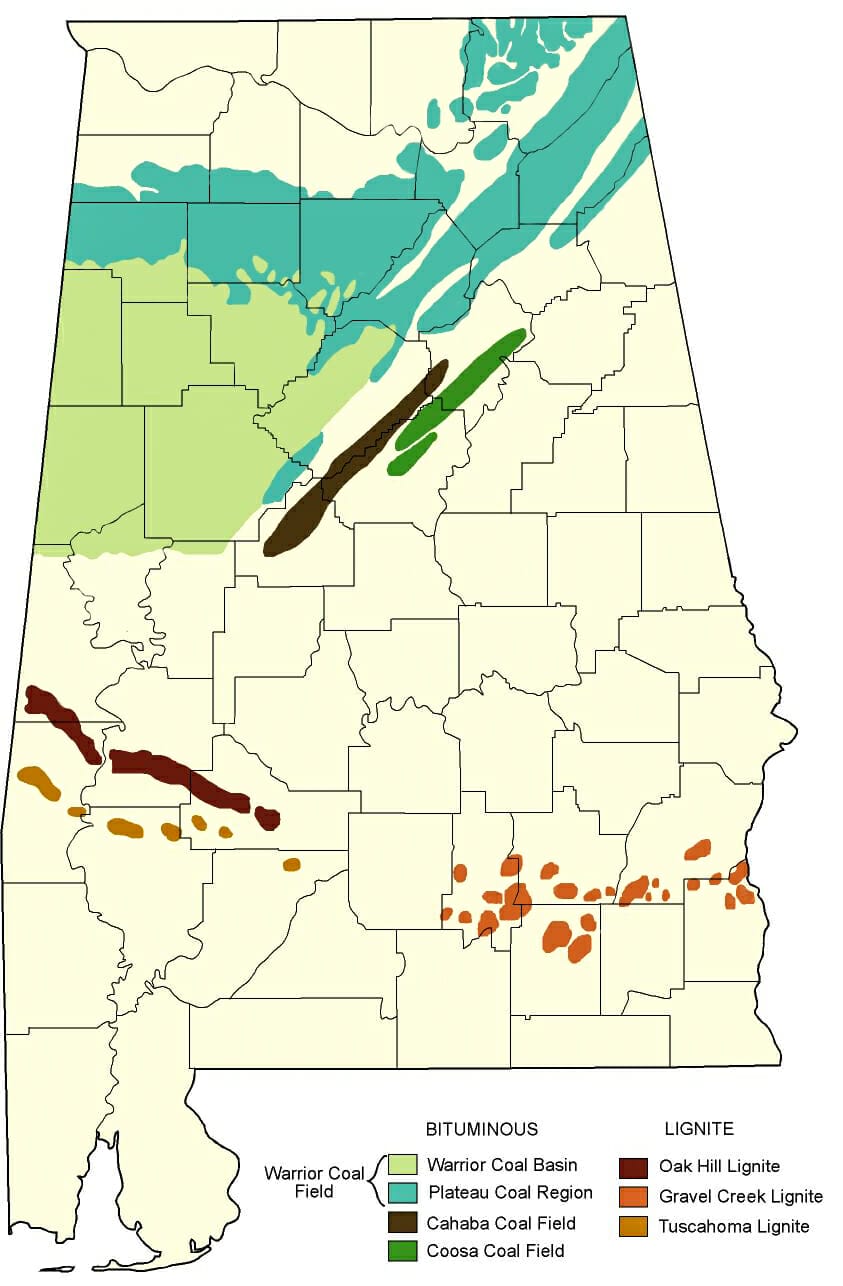

Early accounts suggest that numerous citizens of Bibb, Blount, Jefferson, Shelby, Tuscaloosa, and Walker Counties collected coal from this region as early as the 1830s. During the 1840s, Ambrose Doss and David Hanby attempted to transport flatboats loaded with coal from the Warrior basin to Mobile, but river shoals complicated their efforts. Interested parties soon instituted a more systematic approach, and geologists, mining engineers, and entrepreneurs ultimately discovered four coal fields in Alabama—the Warrior, the Cahaba, the Coosa, and the Plateau. These deposits represent the southern end of the Appalachian coal field, which spans nearly 70,000 square miles and extends from Pennsylvania and Ohio to central Alabama. Later historical summaries, based on reports by state geologist Michael Tuomey in the 1850s, indicated that the first systematic underground mining occurred in the Cahaba field near Montevallo in 1856. Most accounts identify the Alabama Coal Mining Company (ACMC) as the first coal-mining enterprise in that area, but personal records indicate that William Phineas Browne, founder of the Little Cahaba Iron Works, used slave labor to mine coal in the Montevallo area as early as 1849. According to industrial historian Ethel Armes, approximately 200 men were involved in the coal trade in Shelby County by 1850.

William Phineas Browne

Early accounts suggest that numerous citizens of Bibb, Blount, Jefferson, Shelby, Tuscaloosa, and Walker Counties collected coal from this region as early as the 1830s. During the 1840s, Ambrose Doss and David Hanby attempted to transport flatboats loaded with coal from the Warrior basin to Mobile, but river shoals complicated their efforts. Interested parties soon instituted a more systematic approach, and geologists, mining engineers, and entrepreneurs ultimately discovered four coal fields in Alabama—the Warrior, the Cahaba, the Coosa, and the Plateau. These deposits represent the southern end of the Appalachian coal field, which spans nearly 70,000 square miles and extends from Pennsylvania and Ohio to central Alabama. Later historical summaries, based on reports by state geologist Michael Tuomey in the 1850s, indicated that the first systematic underground mining occurred in the Cahaba field near Montevallo in 1856. Most accounts identify the Alabama Coal Mining Company (ACMC) as the first coal-mining enterprise in that area, but personal records indicate that William Phineas Browne, founder of the Little Cahaba Iron Works, used slave labor to mine coal in the Montevallo area as early as 1849. According to industrial historian Ethel Armes, approximately 200 men were involved in the coal trade in Shelby County by 1850.

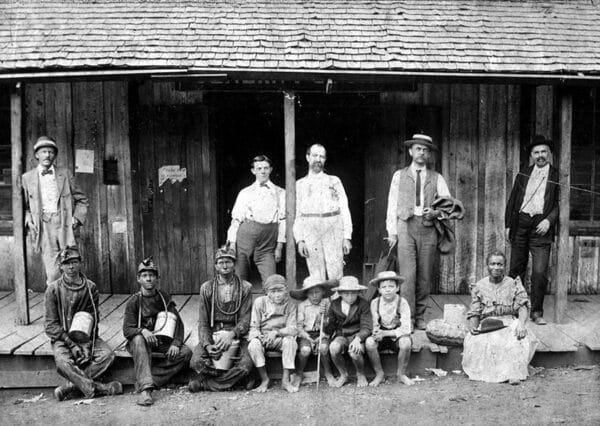

Birmingham Coal Miners

Nineteenth-century miners entered the mines equipped with the tools of their trade: picks, shovels, pry bars, breast augers, saws, axes, and tamping bars. Frequently, mine owners provided the necessary equipment, financing miners’ purchases against future wages. Three-tiered dinner buckets contained their food and drinking water, and kerosene lamps provided dim, smoky lighting. After the turn of the twentieth century, though, carbide lamps replaced the kerosene lights. In the 1930s and 1940s, battery-powered lamps eliminated the need for an open-flame lantern.

Birmingham Coal Miners

Nineteenth-century miners entered the mines equipped with the tools of their trade: picks, shovels, pry bars, breast augers, saws, axes, and tamping bars. Frequently, mine owners provided the necessary equipment, financing miners’ purchases against future wages. Three-tiered dinner buckets contained their food and drinking water, and kerosene lamps provided dim, smoky lighting. After the turn of the twentieth century, though, carbide lamps replaced the kerosene lights. In the 1930s and 1940s, battery-powered lamps eliminated the need for an open-flame lantern.

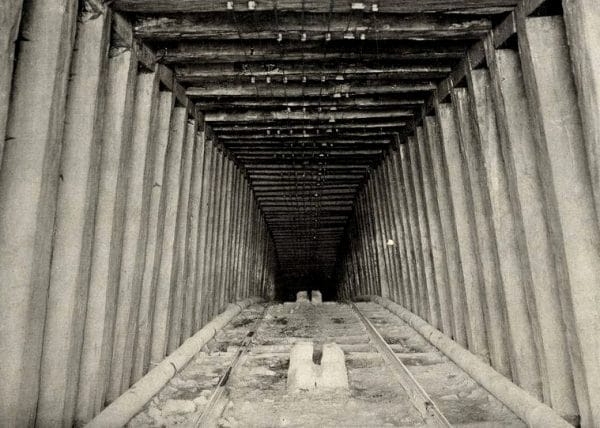

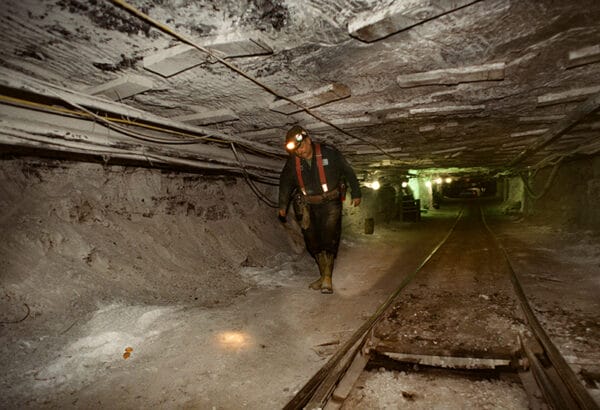

Slope Mine in Jefferson County

In slope and shaft mines, miners removed coal in a four-step process: undercutting, drilling, blasting, and loading. First, miners used picks to carve a three to four foot wedge into the lower part of the face of the coal seam, usually on their knees or lying on their sides. Next, miners used a 5½-foot-long auger with a U-shaped crank to drill holes in the coal face, choosing the location and angle of each hole to maximize the effect of the blast. Miners then blasted the coal from the seam with small black powder charges. After the blast, they returned to the face and shoveled the lumps into trams or cars, each with a one- to two-ton capacity. Mules then pulled five to ten car loads along tracks, and wire ropes or cables hoisted the cars to the mine entrance. Above ground, at the “tipple,” hickory “sprags” immobilized the wheels, checkweighmen weighed each car and credited tonnage to respective miners, and “day men” dumped the coal. Mechanical shakers separated large and medium coal lumps from each other, and smaller pieces, often called nut coal and steam or slack coal, were also separated out.

Slope Mine in Jefferson County

In slope and shaft mines, miners removed coal in a four-step process: undercutting, drilling, blasting, and loading. First, miners used picks to carve a three to four foot wedge into the lower part of the face of the coal seam, usually on their knees or lying on their sides. Next, miners used a 5½-foot-long auger with a U-shaped crank to drill holes in the coal face, choosing the location and angle of each hole to maximize the effect of the blast. Miners then blasted the coal from the seam with small black powder charges. After the blast, they returned to the face and shoveled the lumps into trams or cars, each with a one- to two-ton capacity. Mules then pulled five to ten car loads along tracks, and wire ropes or cables hoisted the cars to the mine entrance. Above ground, at the “tipple,” hickory “sprags” immobilized the wheels, checkweighmen weighed each car and credited tonnage to respective miners, and “day men” dumped the coal. Mechanical shakers separated large and medium coal lumps from each other, and smaller pieces, often called nut coal and steam or slack coal, were also separated out.

This process for extracting coal during the hand-loading period was known as the “room and pillar” method. Adopted in the nineteenth century, this technique persisted until the introduction of mechanical loaders in the 1930s. Miners opened two parallel openings, each 10 to 12 feet wide and situated approximately 30 feet apart. One contained track for transporting coal cars, and the other provided ventilation. Rooms, separated by solid walls of coal known as pillars, opened at right angles from the main headings, and miners tunneled into the coal seam at a rate of 10 to 20 feet per day. Rooms averaged 24 feet wide and between two and eight feet high. When rooms were “mined out,” miners attempted to remove the remaining coal with a dangerous technique known as “pillar robbing,” in which the pillars were pulled out and the unsupported roof then collapsed onto the mine floor.

Jefferson County Strip Mine

Longwall mining, facilitated by the introduction of the mechanical continuous miner, enabled the mass extraction of coal along a lengthy front. In similar fashion, the shortwall method used machinery to work a large portion of the coal face but limited the span to a 150-foot front. This technique proved slightly slower and less efficient than the longwall method, but miners found it safer. As mechanization developed further, surface mining replaced underground mining. Strip mining, a variation of the open pit process used initially in the mid-nineteenth century, used bucket-wheel excavators to remove up to 200 cubic yards of dirt and rock in one bucketful.

Jefferson County Strip Mine

Longwall mining, facilitated by the introduction of the mechanical continuous miner, enabled the mass extraction of coal along a lengthy front. In similar fashion, the shortwall method used machinery to work a large portion of the coal face but limited the span to a 150-foot front. This technique proved slightly slower and less efficient than the longwall method, but miners found it safer. As mechanization developed further, surface mining replaced underground mining. Strip mining, a variation of the open pit process used initially in the mid-nineteenth century, used bucket-wheel excavators to remove up to 200 cubic yards of dirt and rock in one bucketful.

Mining engineer and English émigré Joseph Squire revolutionized coal-mining operations upon his arrival in central Alabama in 1859. Settling in Montevallo, he worked at different times for both Browne and the ACMC. He used practical experience, exploration, testing, charting, and mapping to identify seams and to solve various extraction problems. For the next 50 years, Squire and fellow coal prospector William A. Gould were central figures in the development of Alabama’s coal fields. Mining operations generally followed the pattern established in other coal regions, with drift, shaft, and slope mines being the most typical types. In drift mines, miners dug into outcroppings and followed coal seams along a relatively level path. These mines were easy to navigate but produced relatively little coal. Slopes, although somewhat deeper than drifts, also offered access to coal closer to the surface. In contrast, vertical shaft mines featured elevators that enabled miners to tap the deepest seams. All three types were prevalent in Alabama’s coal fields, but given its ease of access, the slope mine was the most common configuration.

During the Civil War, most of the coal supplied to the Confederacy came from Bibb, Jefferson, Shelby, St. Clair, Tuscaloosa, and Walker Counties. The newly constructed Alabama and Tennessee Rivers Railroad provided access from Montevallo to Selma, and the Cahaba field became the primary source of coal for the Confederate Arsenal and Naval Foundry located there. Rail lines connected Selma to Montgomery and Mobile, and from there steamships carried coal bound for other key cities of the Confederacy. Alabama’s coal and iron industries were devastated in the spring of 1865, however, during a series of cavalry raids by U.S. Army forces under Gen. James H. Wilson.

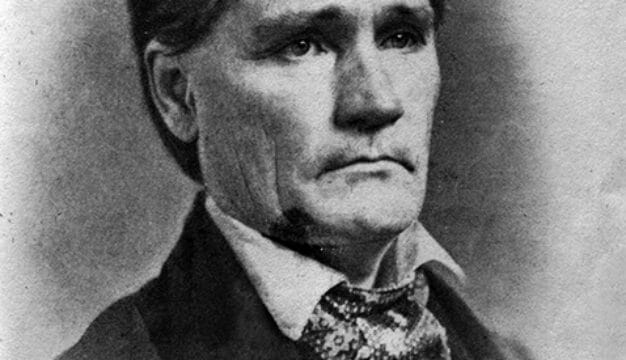

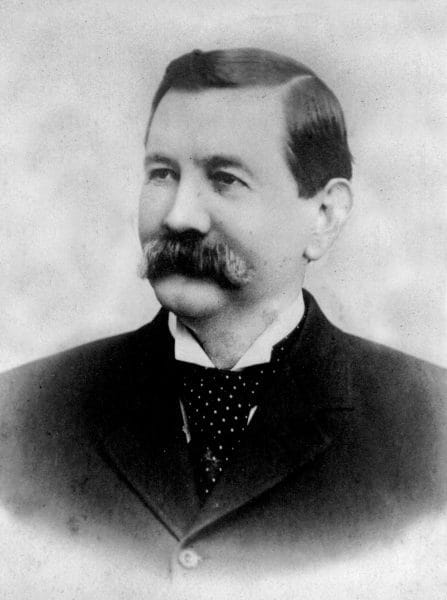

Henry DeBardeleben

Despite numerous attempts to rebuild the state’s industries, coal mines remained relatively dormant until the mid-1870s, when Alabama’s economy began to recover. In 1872, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) completed construction of a main line that connected the Alabama River at Montgomery with the Tennessee River at Decatur. Railroad officials hoped to link Red Mountain iron ore with the coal of the Cahaba field to promote iron production. Consequently, they established Oxmoor furnace near the lines at the foot of Shades Mountain. In 1873, industrialist Daniel Pratt and his son-in-law Henry F. DeBardeleben purchased the Oxmoor furnace in an effort to rebuild central Alabama’s industrial economy. Shortly thereafter, ironmaster Levin S. Goodrich and the Eureka Mining and Transportation Company of Alabama initiated tests to increase production efficiency by reducing the consumption of coal and expanding iron output. He found that coke—a light, porous by-product created when coal is baked for 48 to 72 hours at high temperatures in glazed firebrick (beehive-shaped) ovens—was a better fuel for producing iron. These experiments culminated in the production of coke iron on March 11, 1876, and in Goodrich’s determination that Warrior field coal was the most suitable for making coke.

Henry DeBardeleben

Despite numerous attempts to rebuild the state’s industries, coal mines remained relatively dormant until the mid-1870s, when Alabama’s economy began to recover. In 1872, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) completed construction of a main line that connected the Alabama River at Montgomery with the Tennessee River at Decatur. Railroad officials hoped to link Red Mountain iron ore with the coal of the Cahaba field to promote iron production. Consequently, they established Oxmoor furnace near the lines at the foot of Shades Mountain. In 1873, industrialist Daniel Pratt and his son-in-law Henry F. DeBardeleben purchased the Oxmoor furnace in an effort to rebuild central Alabama’s industrial economy. Shortly thereafter, ironmaster Levin S. Goodrich and the Eureka Mining and Transportation Company of Alabama initiated tests to increase production efficiency by reducing the consumption of coal and expanding iron output. He found that coke—a light, porous by-product created when coal is baked for 48 to 72 hours at high temperatures in glazed firebrick (beehive-shaped) ovens—was a better fuel for producing iron. These experiments culminated in the production of coke iron on March 11, 1876, and in Goodrich’s determination that Warrior field coal was the most suitable for making coke.

DeBardeleben, together with other early Alabama industrialists Truman H. Aldrich and James W. Sloss, formed the Pratt Coal and Coke Company in 1878. With Squire’s assistance, the group opened several slopes and built the Birmingham & Pratt Mines Railroad to link their supply of coking coal with the furnaces of the Birmingham District. These mines would feed the Birmingham iron industry and eventually spawn the development of the mining community known as Pratt City.

Birmingham Coal Mine, 1908

As markets increased, the coal industry relied more heavily on convicts leased from state prisons. In addition to those convicted of crimes, individuals unable to pay fines and court fees were jailed and forced to work off their debts at a standard rate of 30 cents per day. As a result, a two- to four-week sentence could be extended to a maximum of eight months at hard labor in the coal mines, as well as in saw mills and on turpentine farms. Companies paid a fee based on each prisoner’s physical condition, with agreements to provide minimal room, board, and clothing. In effect, convicts could be worked as long and as hard as deemed necessary. Death rates were high, and humanitarian efforts for reform failed repeatedly as special interests in industry and state government worked to undermine them. The convict-lease system was expanded in 1876 to include three-fourths of state inmates and numerous county prisoners. Powerful mining interests kept the system in place, even through such disasters as the 1911 Banner Mine explosion, which killed 125 convicts. Convict leasing persisted for a half-century, terminating on June 30, 1928, with Alabama being the last state to end the practice.

Birmingham Coal Mine, 1908

As markets increased, the coal industry relied more heavily on convicts leased from state prisons. In addition to those convicted of crimes, individuals unable to pay fines and court fees were jailed and forced to work off their debts at a standard rate of 30 cents per day. As a result, a two- to four-week sentence could be extended to a maximum of eight months at hard labor in the coal mines, as well as in saw mills and on turpentine farms. Companies paid a fee based on each prisoner’s physical condition, with agreements to provide minimal room, board, and clothing. In effect, convicts could be worked as long and as hard as deemed necessary. Death rates were high, and humanitarian efforts for reform failed repeatedly as special interests in industry and state government worked to undermine them. The convict-lease system was expanded in 1876 to include three-fourths of state inmates and numerous county prisoners. Powerful mining interests kept the system in place, even through such disasters as the 1911 Banner Mine explosion, which killed 125 convicts. Convict leasing persisted for a half-century, terminating on June 30, 1928, with Alabama being the last state to end the practice.

Birmingham Booms

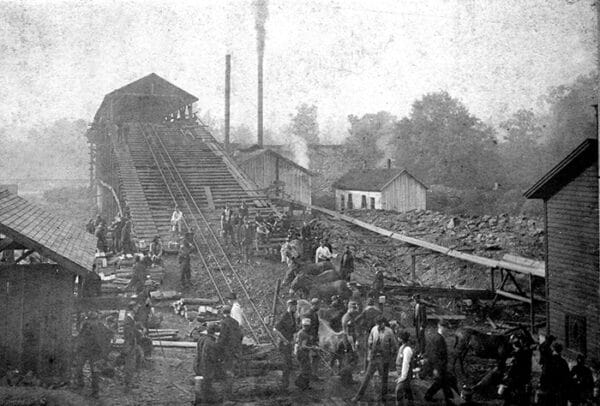

Blocton Coal Mine

Upon completion of the L&N rail line linking Nashville and the Gulf of Mexico, Jones Valley, known for its deposits of coal, iron ore, and limestone, boomed, and Birmingham earned its reputation as the “Magic City.” At the same time, the Pratt Coal and Coke Company established itself as the largest mining operation in the area. Sloss and Aldrich severed ties with DeBardeleben and Pratt Coal and Coke and founded the Sloss Furnace Company and the Cahaba Coal Mining Company (CCMC), respectively. Aldrich’s CCMC, based at Blocton in Bibb County, later comprised more than 1.2 million acres and surpassed DeBardeleben’s Pratt Company as the largest supplier of coke and coal for the Alabama iron industry.

Blocton Coal Mine

Upon completion of the L&N rail line linking Nashville and the Gulf of Mexico, Jones Valley, known for its deposits of coal, iron ore, and limestone, boomed, and Birmingham earned its reputation as the “Magic City.” At the same time, the Pratt Coal and Coke Company established itself as the largest mining operation in the area. Sloss and Aldrich severed ties with DeBardeleben and Pratt Coal and Coke and founded the Sloss Furnace Company and the Cahaba Coal Mining Company (CCMC), respectively. Aldrich’s CCMC, based at Blocton in Bibb County, later comprised more than 1.2 million acres and surpassed DeBardeleben’s Pratt Company as the largest supplier of coke and coal for the Alabama iron industry.

DeBardeleben left Alabama because of health problems and sold the Pratt Company to industrial investor Enoch Ensley and a group of Memphis-based financiers before moving to Mexico. The drier climate helped DeBardeleben regain his health, and he returned to Birmingham in 1885. Partnering with English banker David Roberts, DeBardeleben incorporated two companies in March 1886: DeBardeleben Coal and Iron Company (DCIC), which developed ore and coal mines and built coke ovens and blast furnaces, and Bessemer Land and Improvement Company (BLIC), which speculated on land. The latter firm sold “boom-town” lots to anyone interested in developing a new city named for English steelmaster Sir Henry Bessemer, and DeBardeleben and Roberts hoped that their enterprise would rival Birmingham’s industrial center.

DeBardeleben Coal Mines

As the national economy improved, other investors became interested in Birmingham’s coal and iron industry. The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI) purchased Ensley’s Pratt Coal and Iron Company in 1886. With this takeover, TCI acquired the Pratt mines (which produced more than 3,000 tons of coal daily), two furnaces (and four more under construction), 1,210 coke ovens (with 1,800 under construction), 76,056 acres of coal lands, and 12,204 acres of ore properties. Two years later, this Chattanooga-based conglomerate negotiated an unprecedented 10-year contract with the State of Alabama to lease all state prisoners and half of the county convicts. In sum, TCI emerged as the largest producer of coal and iron in the South. Six years later, the industrial giant absorbed the DeBardeleben Company and Aldrich’s CCMC, thereby doubling its capital stock and land holdings.

DeBardeleben Coal Mines

As the national economy improved, other investors became interested in Birmingham’s coal and iron industry. The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI) purchased Ensley’s Pratt Coal and Iron Company in 1886. With this takeover, TCI acquired the Pratt mines (which produced more than 3,000 tons of coal daily), two furnaces (and four more under construction), 1,210 coke ovens (with 1,800 under construction), 76,056 acres of coal lands, and 12,204 acres of ore properties. Two years later, this Chattanooga-based conglomerate negotiated an unprecedented 10-year contract with the State of Alabama to lease all state prisoners and half of the county convicts. In sum, TCI emerged as the largest producer of coal and iron in the South. Six years later, the industrial giant absorbed the DeBardeleben Company and Aldrich’s CCMC, thereby doubling its capital stock and land holdings.

Coal Train

Alabama coal companies suffered when the economic Panic of 1893 reduced demand for coal and reversed the growing trend toward prosperity. TCI stock prices plummeted, and both DeBardeleben and Aldrich were forced out of the company in 1894. Their ouster marked the end of a prosperous yet volatile era, but mining efforts in the last half of the nineteenth century laid the groundwork for the coal boom of the first half of the twentieth century. As the iron and steel industry of the Birmingham District tapped coal reserves from the Warrior field, many individual investors sought their fortunes among Alabama’s “black diamonds.” Once established, these coal-mining ventures attracted waves of workers and their families.

Coal Train

Alabama coal companies suffered when the economic Panic of 1893 reduced demand for coal and reversed the growing trend toward prosperity. TCI stock prices plummeted, and both DeBardeleben and Aldrich were forced out of the company in 1894. Their ouster marked the end of a prosperous yet volatile era, but mining efforts in the last half of the nineteenth century laid the groundwork for the coal boom of the first half of the twentieth century. As the iron and steel industry of the Birmingham District tapped coal reserves from the Warrior field, many individual investors sought their fortunes among Alabama’s “black diamonds.” Once established, these coal-mining ventures attracted waves of workers and their families.

Company Towns

Pratt Company Commissary, 1916

As coal and coke production increased, many mining companies constructed thriving communities. Centrally located, the company store provided a common gathering place for town residents. Family dwellings, boarding houses, and retail stores lined the streets and generated a bustling air. Churches, schools, and fraternal organizations fostered a community spirit and helped establish a stable social order. Circuses, boxing matches, and civic functions provided entertainment, and company-sponsored baseball teams, community bands, and bicycle clubs offered recreational opportunities. Increased demand for coal coincided with an agrarian crisis that prompted workers to migrate from farming areas to relatively remote mining sites. For many, life on the farm offered little promise, and families often moved to coal towns like Blocton, Piper, Aldrich, and Margaret in search of economic opportunity and a better way of life. In general, regular work meant more dependable income, but deductions for company services and payments in scrip frequently undercut a miner’s pay.

Pratt Company Commissary, 1916

As coal and coke production increased, many mining companies constructed thriving communities. Centrally located, the company store provided a common gathering place for town residents. Family dwellings, boarding houses, and retail stores lined the streets and generated a bustling air. Churches, schools, and fraternal organizations fostered a community spirit and helped establish a stable social order. Circuses, boxing matches, and civic functions provided entertainment, and company-sponsored baseball teams, community bands, and bicycle clubs offered recreational opportunities. Increased demand for coal coincided with an agrarian crisis that prompted workers to migrate from farming areas to relatively remote mining sites. For many, life on the farm offered little promise, and families often moved to coal towns like Blocton, Piper, Aldrich, and Margaret in search of economic opportunity and a better way of life. In general, regular work meant more dependable income, but deductions for company services and payments in scrip frequently undercut a miner’s pay.

Birmingham Coal Miners, 1937

Like virtually all other aspects of Alabama society, the coal industry was segregated. From the end of the nineteenth century to the 1930s, approximately one-half of all coal miners in Alabama were African American, and Blacks comprised more than 90 percent of convict miners. The 1890 U.S. Census indicates that African Americans made up 46.2 percent of the mining population. Native-born white miners comprised 34.9 percent, and 18.7 percent consisted primarily of Southern and Eastern European immigrants. Four decades later, the proportion of black miners expanded to 53.2 percent, whereas native-born whites increased to 45.3 percent and immigrants decreased to 1.5 percent, as the waves of immigration that characterized the turn of the century came to an end.

Birmingham Coal Miners, 1937

Like virtually all other aspects of Alabama society, the coal industry was segregated. From the end of the nineteenth century to the 1930s, approximately one-half of all coal miners in Alabama were African American, and Blacks comprised more than 90 percent of convict miners. The 1890 U.S. Census indicates that African Americans made up 46.2 percent of the mining population. Native-born white miners comprised 34.9 percent, and 18.7 percent consisted primarily of Southern and Eastern European immigrants. Four decades later, the proportion of black miners expanded to 53.2 percent, whereas native-born whites increased to 45.3 percent and immigrants decreased to 1.5 percent, as the waves of immigration that characterized the turn of the century came to an end.

As a rule, segregation among miners existed above ground because companies provided separate neighborhoods for the different groups. When underground, however, miners earned equal pay for equal work and endured the same hazards and risks of a dangerous occupation. Still, owners and operators often used racial and ethnic differences to pit one group of miners against another in an effort to keep them from organizing.

Labor Relations

Erskine Ramsay Guards, 1894

Miners’ attempts to bargain for wages and better working conditions began with the Greenback-Labor Party (GLP) in 1878. Shortly thereafter, the Knights of Labor replaced the GLP as the most popular labor organization. Both groups contributed to an interracial movement that combined labor organization with political activism and gave rise to the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) as the predominant labor organization of the 1890s. An initial strike by the UMWA in late 1890 set the tone for labor conflicts for the next four decades. Miners demanded collective bargaining, payroll deduction of union dues, a standard eight-hour day and 40-hour week, medical care, safety regulations, and mine inspections. Common class interests brought coal miners together in interracial labor organizations, but operators used black strikebreakers to force a racial wedge between white and black workers. Company officials often used immigrant miners as strikebreakers as well. Subsequent strikes in 1894, 1904, 1908, and 1920 failed as a result of state support for the operators. Labor unions struggled to survive until collective bargaining gained sanction with the New Deal legislation of the 1930s.

Erskine Ramsay Guards, 1894

Miners’ attempts to bargain for wages and better working conditions began with the Greenback-Labor Party (GLP) in 1878. Shortly thereafter, the Knights of Labor replaced the GLP as the most popular labor organization. Both groups contributed to an interracial movement that combined labor organization with political activism and gave rise to the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) as the predominant labor organization of the 1890s. An initial strike by the UMWA in late 1890 set the tone for labor conflicts for the next four decades. Miners demanded collective bargaining, payroll deduction of union dues, a standard eight-hour day and 40-hour week, medical care, safety regulations, and mine inspections. Common class interests brought coal miners together in interracial labor organizations, but operators used black strikebreakers to force a racial wedge between white and black workers. Company officials often used immigrant miners as strikebreakers as well. Subsequent strikes in 1894, 1904, 1908, and 1920 failed as a result of state support for the operators. Labor unions struggled to survive until collective bargaining gained sanction with the New Deal legislation of the 1930s.

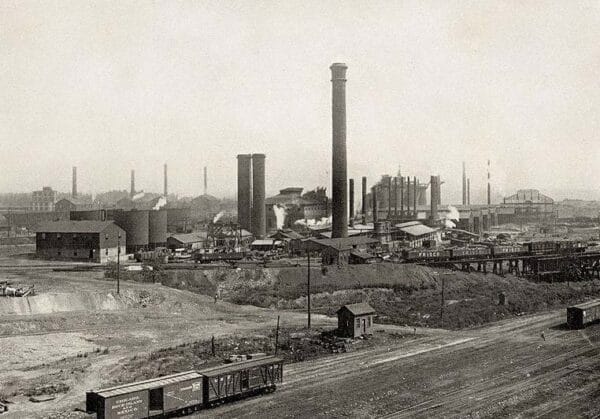

Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Co.

Some companies, including TCI, the Montevallo Coal and Transportation Company, and the Alabama Fuel and Iron Company, attempted to undermine organizing efforts by adopting a more paternalistic approach. Adopting welfare capitalism as their creed, companies converted a portion of their assets into schools, churches, recreation centers, libraries, and beauty parlors to appeal to families. As workers’ quality of life improved, company towns assumed a community spirit. Thus welfare capitalism appeared mutually beneficial. Operators provided company houses, doctors, sports teams, stocks, and “welfare societies,” but humanitarian concern for the workers did not necessarily define the central motivation for such action. Opposing viewpoints from labor historians suggest that companies provided benefits to appease the work force and to maintain social control within the company towns.

Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Co.

Some companies, including TCI, the Montevallo Coal and Transportation Company, and the Alabama Fuel and Iron Company, attempted to undermine organizing efforts by adopting a more paternalistic approach. Adopting welfare capitalism as their creed, companies converted a portion of their assets into schools, churches, recreation centers, libraries, and beauty parlors to appeal to families. As workers’ quality of life improved, company towns assumed a community spirit. Thus welfare capitalism appeared mutually beneficial. Operators provided company houses, doctors, sports teams, stocks, and “welfare societies,” but humanitarian concern for the workers did not necessarily define the central motivation for such action. Opposing viewpoints from labor historians suggest that companies provided benefits to appease the work force and to maintain social control within the company towns.

Jim Walter Mine

Coal mining operations enjoyed high demand and constant work during World War I and World War II. Consumption rates for natural gas, petroleum products, and hydroelectric power increased as well. Meanwhile, the introduction of improved mechanization made surface mining a more profitable undertaking than underground mining. By the 1950s, , however, coal markets were in severe decline and most of Alabama’s mines closed. Some operations continued, but most were constrained by newly enacted environmental protection laws, land reclamation expenses, safety regulations, and rising labor costs.

Jim Walter Mine

Coal mining operations enjoyed high demand and constant work during World War I and World War II. Consumption rates for natural gas, petroleum products, and hydroelectric power increased as well. Meanwhile, the introduction of improved mechanization made surface mining a more profitable undertaking than underground mining. By the 1950s, , however, coal markets were in severe decline and most of Alabama’s mines closed. Some operations continued, but most were constrained by newly enacted environmental protection laws, land reclamation expenses, safety regulations, and rising labor costs.

Jefferson County Coal Miners

The demise of iron and steel plants in the 1970s and the more recent closures of coal-fired power plants caused many company bankruptcies. In other cases, less expensive extraction methods and cheaper labor offset transportation costs as many coal companies looked to other states and to foreign countries for fossil fuels. Even though most of Alabama’s coal deposits lie dormant, coal mining continues to serve the remaining electrical power plants and the strong global demand for metallurgical coal exported through the Port of Mobile. Several deep coal mines produce coal using highly automated longwall mining systems.

Jefferson County Coal Miners

The demise of iron and steel plants in the 1970s and the more recent closures of coal-fired power plants caused many company bankruptcies. In other cases, less expensive extraction methods and cheaper labor offset transportation costs as many coal companies looked to other states and to foreign countries for fossil fuels. Even though most of Alabama’s coal deposits lie dormant, coal mining continues to serve the remaining electrical power plants and the strong global demand for metallurgical coal exported through the Port of Mobile. Several deep coal mines produce coal using highly automated longwall mining systems.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reports that in 2019 approximately 14 million short tons of coal were produced in Alabama. Eighty percent of that total came from seven underground mines and 22 surface mines. The Port of Mobile is an important transportation center for coal. It ranks as the largest port of entry for handling coal imports to the United States and is the nation’s third largest for handling coal exports. Only 10 percent of the coal produced in Alabama is consumed within the state; 60 percent of the coal used for electrical power generation in Alabama now comes from Wyoming, which has cleaner-burning coal.

Further Reading

- Armes, Ethel. The Story of Coal and Iron in Alabama. Birmingham: Chamber of Commerce, 1910.

- Day, James Sanders. “‘Diamonds in the Rough’: A History of Alabama’s Cahaba Coal Field.” Ph.D. diss., Auburn University, 2002.

- Lewis, W. David. Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham District: An Industrial Epic. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1994.

- Ward, Robert David, and William Warren Rogers. Convicts, Coal, and the Banner Mine Tragedy. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1987.