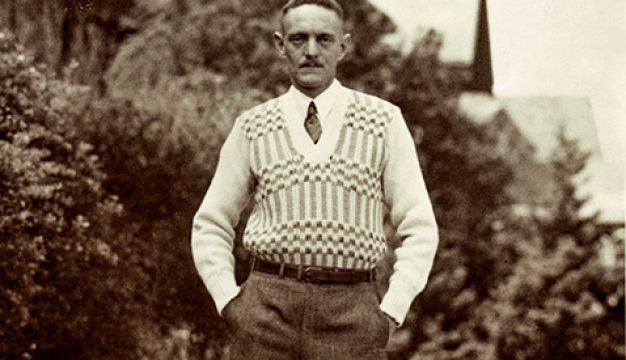

Williamson Cobb

Williamson Cobb

Williamson Robert Winfield Cobb (1807-1864) was a merchant, plantation owner, and politician who served in the Alabama House of Representatives (1845-1847) and the U.S. House of Representatives (1847-1861) and was elected to the Confederate House of Representatives but never served. A progressive Democrat and ardent Unionist, he worked to keep Alabama in the Union and to strike a compromise to avert the Civil War. Historians recently discovered that he was to be appointed by Pres. Abraham Lincoln to become the provisional governor of Alabama in the event that it fell into Union hands either during or after the war.

Williamson Cobb

Williamson Robert Winfield Cobb (1807-1864) was a merchant, plantation owner, and politician who served in the Alabama House of Representatives (1845-1847) and the U.S. House of Representatives (1847-1861) and was elected to the Confederate House of Representatives but never served. A progressive Democrat and ardent Unionist, he worked to keep Alabama in the Union and to strike a compromise to avert the Civil War. Historians recently discovered that he was to be appointed by Pres. Abraham Lincoln to become the provisional governor of Alabama in the event that it fell into Union hands either during or after the war.

Cobb was born in Rhea County, Tennessee, on June 8, 1807, to David Cobb and Martha Bryant Cobb. In 1809, his father settled on a cotton plantation in Bellefontaine or Bellafonte, Madison County, where Cobb spent most of his childhood. Receiving little formal education, he tried his hand selling clocks and then worked as a merchant, achieving reasonable success in this endeavor. In 1825, he married Catherine Allison; the couple had no children. In 1844, Cobb ran for Madison County's seat in the Alabama House of Representatives. His lack of education and vernacular speaking manner made him appealing to the largely rural and largely uneducated white voters of northern Alabama, who were drawn to his "everyman" personality and voted overwhelmingly in his favor.

Cobb soon established himself in the legislature as a defender of poor whites by supporting legislation that prevented certain household articles from being sold by county officials when a person could not repay their debts. Cobb then used this reputation to launch a successful bid in 1847 against William Acklin for the Sixth Congressional District seat vacated by Reuben Chapman, who was running for governor. In 1848, Cobb voted to extend the western border separating slave-holding from non-slave states, established by the Missouri Compromise, to the West Coast in an effort to temper the flaring sectional crisis.

Cobb went on to defeat former state legislator Jeremiah Clemens in 1849 and quickly developed a loyal and devoted voting base. (Clemens was later elected that year to the U.S. Senate.) His continued appeal among the masses and his popularity with the poor and uneducated threatened elite landowners, who generally controlled Alabama politics in the period. In response, members of the Huntsville aristocracy fielded Clement Claiborne Clay in 1853 as Cobb's pro-slavery opponent. However, because northern Alabama consisted mainly of small farmers, few enslaved people, mostly pro-Unionists, and few individuals with much formal education, Cobb was seen as someone who stood up against aristocratic interests and carried all but one county in the election. This solid base of support led to his reelection for six consecutive terms.

As chairman of the Committee on Public Lands, he avidly supported "graduation" bills, which lowered the price of land the longer it remained on the market, and homesteading legislation that proposed the sale or donation of lands in the West to settlers who agreed to establish farms there. These proposals also appealed to his constituents in northern Alabama, where there were more than 14 million acres that they hoped to buy cheaply.

Various graduation bills had already stalled in Congress when Cobb proposed the Graduation Act of 1854, which priced public land on the market for more than 10 years anywhere from $1.00 an acre to as low as 12.5 cents per acre. Cobb's bill became law that year. Its passage sparked a land rush out West as settlers poured in from the eastern and southern states before the Homestead Act replaced it in 1862. Some eastern and southern politicians feared the sales out West would drain people from their own states and increase land speculation. Economically and politically though, the act accelerated the development of the West and frustrated many southern politicians, because anti-slavery settlers quickly bought up lands in the West in an attempt to establish free states and tip the balance of power in Congress in their favor.

In these years prior to the Civil War, Cobb worked to keep his district loyal to the Union as support for secession rose in Alabama. After the state passed its Ordinance of Secession in January 1861, he appealed to his fellow representatives for peace and compromise before becoming the last congressman from the state to leave Washington. He returned home to his plantation in Madison County and decided to run against secessionist John P. Ralls for a seat in the Confederate House of Representatives. But, for the first time in his political career, he was soundly defeated. Undeterred, Cobb ran against Ralls again in 1863 and won because of the growing disillusionment among northern Alabamians towards the Confederate war effort.

As Cobb continued to run his farm, newspapers in Richmond, Virginia, printed rumors of his supposedly frequent clandestine liaisons with Union authorities in the Tennessee Valley. When he failed to report to the Confederate Congress in Richmond to assume his new seat, the Confederate House created a committee on May 3, 1864, to investigate charges of disloyalty. Just five months later, on November 1, 1864, while putting up a fence on his plantation, Cobb accidentally dropped his pistol, which discharged and mortally wounded him. Just 16 days later, the Confederate House voted 75 to 0 in favor of expelling Cobb from the Confederate Congress, apparently unaware of his death. Cobb was buried on the Cobb family estate near Cobb's Bridge in Madison County.

After his death, rumors about Cobb's disloyalty continued to circulate, with new claims that Cobb had been commissioned by Pres. Abraham Lincoln as the provisional governor of Alabama. In 2004, archivists at the Jackson County Courthouse in Scottsboro discovered a payment voucher signed by Lincoln confirming this rumor. There is no evidence, however, that the voucher was ever redeemed and that Cobb ever accepted the commission.

Further Reading

- Atkins, Leah. "Williamson R. W. Cobb and the Graduation Act of 1854." Alabama Review 28 (January 1975): 16-31.

- Brewer, Willis. Alabama, Her History, Resources, War Record, and Public Men: from 1540 to 1872. Montgomery, Ala.: Barrett & Brown, 1872.

- Severance, Ben H. Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Alabama During the Civil War. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2012.

- Storey, Margaret M. Loyalty and Loss: Alabama's Unionists in the Civil War and Reconstruction (Conflicting Worlds: New Dimensions of the American Civil War). Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press, 2004.