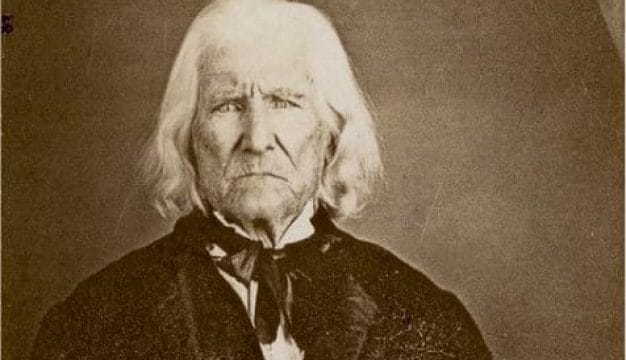

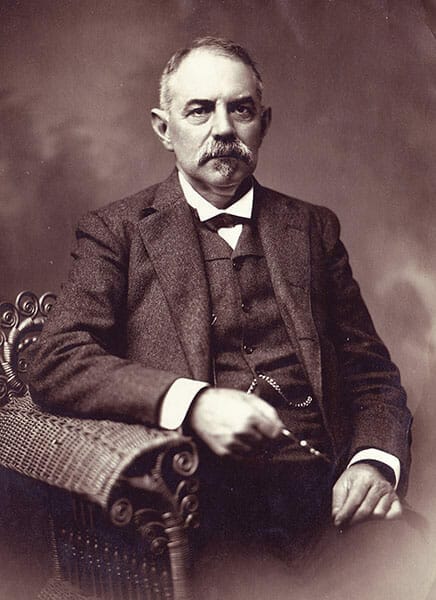

William Calvin Oates (1894-96)

William Calvin Oates

Alabama governor William C. Oates (1835-1910) rose from rough and humble beginnings to run a newspaper, serve as an officer with the Confederate Army at Gettysburg and other major Civil War battles, and won election to the U.S. Congress. A staunch Democrat and white supremacist, he entered state politics to stave off a Populist movement that would have placed political power in the hands of small farmers and freedmen. He was a major figure in the Big Mule-Black Belt coalition and successfully derailed investigations into Alabama‘s questionable election practices, and after leaving office as governor, worked toward the disenfranchisement of blacks and poor whites in the 1901 Constitution.

William Calvin Oates

Alabama governor William C. Oates (1835-1910) rose from rough and humble beginnings to run a newspaper, serve as an officer with the Confederate Army at Gettysburg and other major Civil War battles, and won election to the U.S. Congress. A staunch Democrat and white supremacist, he entered state politics to stave off a Populist movement that would have placed political power in the hands of small farmers and freedmen. He was a major figure in the Big Mule-Black Belt coalition and successfully derailed investigations into Alabama‘s questionable election practices, and after leaving office as governor, worked toward the disenfranchisement of blacks and poor whites in the 1901 Constitution.

William Calvin Oates enjoyed neither a comfortable childhood nor an excellent education. The eldest child of William and Sarah Sellers Oates, William was born on November 30, 1835, in Pike County. His father, who had moved to Alabama’s Wiregrass region from South Carolina, was a poor farmer who had little to offer his wife and children but a life of isolation and endless toil. Young Oates was ambitious, but his father had no money for his education. Oates attended a few school sessions after scraping together tuition by working on neighboring farms. As a child, he developed a penchant for getting into trouble, and in 1851, after committing assault, he decided to leave home and see more of the world.

Oates embarked on a three-year adventure, earning his keep as a cigar-seller, house painter, deckhand, shingle-maker, and gambler. He stayed briefly in northern Florida, Louisiana, and various Texas towns. Early in 1854 the still-teenaged Oates returned to Alabama and settled in Henry County, in the Wiregrass, where he found a job teaching school. Beginning in 1855, Oates began alternating teaching and studying at Lawrenceville Academy, where schoolmaster William A. Clark and his staff instructed the young man in English composition, mathematics, Latin, and debate. Oates worked hard and excelled, graduating in just two years. With an interest in public affairs, Oates turned to the study of law, which he saw as a means of improving his social position. In 1858, he travelled to Eufaula to read law with the firm of James L. Pugh, Edward C. Bullock, and Jefferson Buford, lawyers who were members of a pro-secession group known as the Regency. In October, Oates earned his license and two months later opened an office in the nearby town of Abbeville.

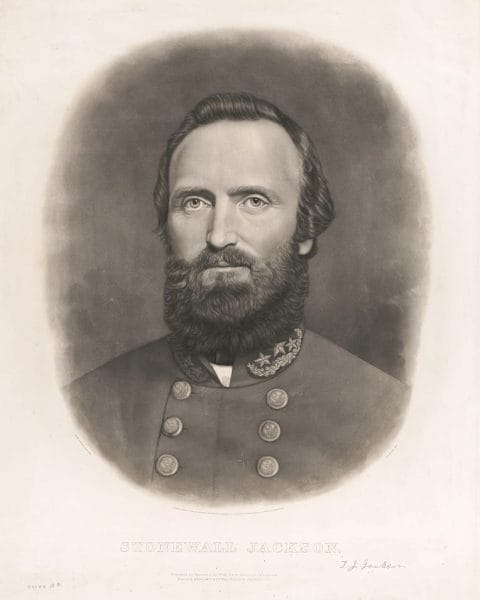

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson

By 1860, Oates was supplementing his income as the editor of a Democratic newspaper. Though not an enthusiastic secessionist, he supported the action of Alabama’s January 1861 convention. When the Civil War began, he foresaw that future rank and social position would follow military glory. Accordingly, he raised an infantry company, the Henry [County] Pioneers, and worked hard to provide them uniforms and equipment. The company left Abbeville in July 1861 and was soon in Virginia as Company G of the Fifteenth Alabama regiment. In May and June of 1862, Oates and his men served with Stonewall Jackson in his Valley Campaign. By January 1863, 28-year-old Oates was given the rank of colonel and placed in command of the regiment, a reward he gained not only for bravery but for the care with which he led his troops.

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson

By 1860, Oates was supplementing his income as the editor of a Democratic newspaper. Though not an enthusiastic secessionist, he supported the action of Alabama’s January 1861 convention. When the Civil War began, he foresaw that future rank and social position would follow military glory. Accordingly, he raised an infantry company, the Henry [County] Pioneers, and worked hard to provide them uniforms and equipment. The company left Abbeville in July 1861 and was soon in Virginia as Company G of the Fifteenth Alabama regiment. In May and June of 1862, Oates and his men served with Stonewall Jackson in his Valley Campaign. By January 1863, 28-year-old Oates was given the rank of colonel and placed in command of the regiment, a reward he gained not only for bravery but for the care with which he led his troops.

At Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, Oates and the 15th Alabama gained lasting fame by repeatedly assaulting Little Round Top, defended by the men of the 20th Maine. In the brutal and deadly confrontation, the 400 Alabamians suffered 138 casualties in a long day’s struggle that ended in defeat for the southern forces. Following Gettysburg, Oates’s regiment was transferred to Tennessee, where it performed well at the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863. Oates was shot in the thigh during the battle. By March 1864, he had returned to his command and was ordered north, where he and his men participated in the battles of the Wilderness and Cold Harbor in May.

In August, Oates was replaced in command by his subordinate, Maj. Alexander Lowther. Oates’s most recent biographer suggests that he may have damaged his career by advocating (as early as February 1863) that the Confederacy enlist the South’s enslaved population to offset the Union edge in manpower. Years later, Oates was still angry that Confederate leaders had, as he thought, preserved slavery at the cost of victory. He was given command of the 48th Alabama regiment as a consolation prize. But on August 16, 1864, near Petersburg, Virginia, he was wounded seriously in his right arm, necessitating an amputation. When Lee surrendered to Grant, Oates was at home in Abbeville, recuperating from the injury that became his political badge of honor.

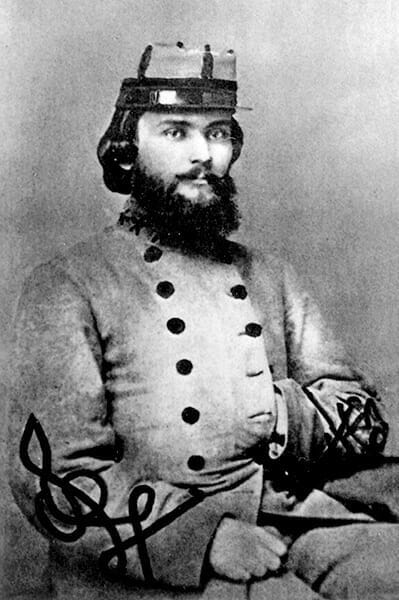

William Calvin Oates, ca. 1860s

Upon his return to health, Oates picked up the pieces of his life. He reopened his legal practice, which allowed him to harness his combative streak in civilian life. Like many ex-Confederates, Oates was loyal to the Democratic Party and viewed Republicans as enemies and looters of the public treasury. Oates disapproved of the violent methods of the Ku Klux Klan but did not hesitate to endorse ballot-box stuffing, bribery, or other means of controlling the votes of the freedmen—all of which Democrats carried out in the name of white supremacy. Forced to accept the suffrage of black men, he became an architect of the system by which “Bourbon” (ultraconservative) Democrats produced majorities sufficient to defeat Republicans and Independents. The Bourbons were concentrated geographically in the state’s Black Belt counties. In cooperation with industrialists and business interests in Birmingham and other cities, known as Big Mules, they dominated Alabama politics during the quarter-century after 1874—the year that Reconstruction ended in Alabama.

William Calvin Oates, ca. 1860s

Upon his return to health, Oates picked up the pieces of his life. He reopened his legal practice, which allowed him to harness his combative streak in civilian life. Like many ex-Confederates, Oates was loyal to the Democratic Party and viewed Republicans as enemies and looters of the public treasury. Oates disapproved of the violent methods of the Ku Klux Klan but did not hesitate to endorse ballot-box stuffing, bribery, or other means of controlling the votes of the freedmen—all of which Democrats carried out in the name of white supremacy. Forced to accept the suffrage of black men, he became an architect of the system by which “Bourbon” (ultraconservative) Democrats produced majorities sufficient to defeat Republicans and Independents. The Bourbons were concentrated geographically in the state’s Black Belt counties. In cooperation with industrialists and business interests in Birmingham and other cities, known as Big Mules, they dominated Alabama politics during the quarter-century after 1874—the year that Reconstruction ended in Alabama.

In 1880, Oates was rewarded for his service to the Confederacy and loyalty to the Democratic Party with a seat in the U.S. Congress from the Third District. Backed by a network of veterans, he was unbeatable, winning reelection six times. A large part of his success in Washington was owed to the charm and ability of Sarah Toney Oates, whom he married in 1882. The daughter of a Eufaula family, she was 27 years younger than Oates. Despite her youth, she was a natural-born political hostess. In addition, Oates won respect in Congress as a skilled parliamentarian and determined conservative. In the House, he opposed both the Blair bill, which would have spent federal funds on public education, and the Interstate Commerce Act, designed to regulate railroads. In the early 1890s, a time of declining crop prices, widespread foreclosures, and furious anger on southern farms, Oates remained a staunch supporter of the gold standard and a foe of measures intended to promote currency inflation.

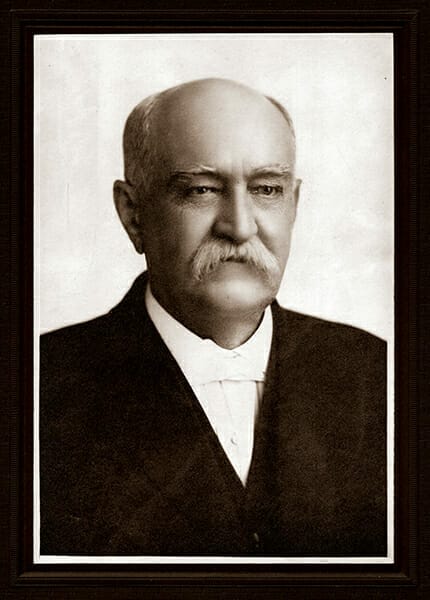

Thomas Goode Jones

Oates’s chief ambition was to advance to a Senate seat, but his plans changed as a result of the state politics of the 1890s. In response to declining prices, thousands of small farmers joined such organizations as the Farmer’s Alliance, which urged farmers to buy and sell cooperatively and advocated a greatly inflated national currency. Democratic leaders, in the meantime, split over the stance of the party toward the Alliance and similar groups. Alliance leader Reuben F. Kolb was denied the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 1890 by a coalition of the Black Belt and pro-business delegates. In 1892, Kolb broke with the party and ran as the candidate of the “Jeffersonian Democrats,” openly soliciting the votes of black farmers. His campaign against incumbent governor Thomas Goode Jones and his effort to bypass the politics of white supremacy were both infuriating and frightening to conservatives like Oates.

Thomas Goode Jones

Oates’s chief ambition was to advance to a Senate seat, but his plans changed as a result of the state politics of the 1890s. In response to declining prices, thousands of small farmers joined such organizations as the Farmer’s Alliance, which urged farmers to buy and sell cooperatively and advocated a greatly inflated national currency. Democratic leaders, in the meantime, split over the stance of the party toward the Alliance and similar groups. Alliance leader Reuben F. Kolb was denied the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 1890 by a coalition of the Black Belt and pro-business delegates. In 1892, Kolb broke with the party and ran as the candidate of the “Jeffersonian Democrats,” openly soliciting the votes of black farmers. His campaign against incumbent governor Thomas Goode Jones and his effort to bypass the politics of white supremacy were both infuriating and frightening to conservatives like Oates.

Kolb lost to Jones by a margin of 126,959 to 115,524, almost certainly as a result of ballot fraud in the Black Belt. Kolb clearly planned to run again in 1894 as the Jeffersonian candidate and expected the support of a radical pro-inflationist party, the People’s Party or Populists. The Democratic political bosses united behind Oates as a man who had opposed the Alliance and who could best fight off the challenge of a growing “Silverite” (Free Silver or inflationist) wing within the Democratic Party. Backed by Jones and the Montgomery Advertiser, Oates ran for governor. At the Democratic convention in May 1894, he defeated Birmingham Silverite Joseph F. Johnston on the first ballot. Oates’s campaign against Kolb competed for newspaper coverage with Jones’s use of troops to put down a strike by Birmingham coal miners. Kolb and his Populist and Republican allies turned their fire against Jones, while Oates ran as the “One-Armed Hero of Henry County,” foe of anarchy and disorder, defender of white supremacy.

Reuben F. Kolb

In the August 1894 election, Oates defeated Kolb by a count of 111,875 to 83,292 votes. As in 1892, Democratic victory was partly the result of stuffed ballot boxes in the Black Belt. The decline in the number of ballots was probably the result of the Sayre election law of 1893, a measure designed to deprive illiterates of the vote. Kolb and many of his supporters refused to accept the official returns. Kolb declared himself the victor and on inauguration day, December 1, 1894, took an oath of office from a Montgomery justice of the peace. With a band of loyal followers, he marched up Dexter Avenue to the capitol grounds, where under the noses of Governor Jones and incoming Governor Oates, who were protected by state troops, he was forced onto a side street. Kolb delivered an “inaugural” address to his angry supporters, but Oates was peacefully and officially sworn in as governor. His congressional seat was taken by George Paul Harrison Jr.

Reuben F. Kolb

In the August 1894 election, Oates defeated Kolb by a count of 111,875 to 83,292 votes. As in 1892, Democratic victory was partly the result of stuffed ballot boxes in the Black Belt. The decline in the number of ballots was probably the result of the Sayre election law of 1893, a measure designed to deprive illiterates of the vote. Kolb and many of his supporters refused to accept the official returns. Kolb declared himself the victor and on inauguration day, December 1, 1894, took an oath of office from a Montgomery justice of the peace. With a band of loyal followers, he marched up Dexter Avenue to the capitol grounds, where under the noses of Governor Jones and incoming Governor Oates, who were protected by state troops, he was forced onto a side street. Kolb delivered an “inaugural” address to his angry supporters, but Oates was peacefully and officially sworn in as governor. His congressional seat was taken by George Paul Harrison Jr.

The 1894-1895 legislature pitted Populists against Democrats, Bourbons against reform Democrats, and Gold Standard men against Silverites. The Populists constituted a substantial minority whose first objective was a passage of an effective election contest law. Eventually the legislature passed a contest act, which though not retroactive, was supported by Populist leaders such as Joseph C. Manning as the best they could get. The legislative session was marked by constant efforts on the part of the Populists to draw the federal government into an investigation of Alabama’s 1892 and 1894 election outcomes. Oates and his allies defeated the Populists at every turn.

Oates’s chief concern as governor was the financial stability of the state. Previous administrations had successively lowered the rate of ad valorem taxation from 7.5 mills in 1876 to 4 mills in 1889, as state expenditures had doubled. In the economically depressed early 1890s, Governor Jones had been forced to borrow money to keep the government in operation and had approved a half-mill tax increase in 1893. Even so, in 1894 he projected a deficit of nearly $700,000 by September 1896. Oates’s allies in the legislature rushed through another half-mill tax in December over the opposition of Populists who hoped to see the Oates administration short of funds. In February 1895, after much debate, the legislature passed bills that authorized Oates to seek refinancing of the state’s bonded indebtedness. In the same month, at Oates’s request, the lawmakers repealed Governor Jones’s plan to phase out the convict-lease system, thus preserving a vital source of revenue for the state and a convenient though brutal form of labor control for industrialists.

In March 1895, Oates travelled to New York to meet with the state’s creditors about Alabama’s bonded debt. There he was ambushed by Joseph Manning and Populist congressman Milford W. Howard, who were in town to publicize the need for ballot reform in the South. They denounced Oates as governor by fraud, head of an unjust regime. Oates was unable to make satisfactory fiscal arrangements and returned to Alabama in a poor state of health and nerves. Over the next year, hard times persisted, and Oates was forced to borrow money for the state from bankers in New York, Selma, and Mobile. He could take comfort, however, in the knowledge that Populist efforts to overturn the 1894 election had failed. By May 1896, it was clear that Congress would conduct no investigations into Alabama elections.

William Calvin Oates and Men, 1898

Despite this victory, Oates’s Democratic allies suffered setbacks. The Silverites were still a strong faction, and Oates could not prevent Johnson, the pro-silver candidate, from winning the Democratic gubernatorial nomination. With his term drawing to an end, Oates still dreamed of a U.S. Senate seat. A vacancy was due to be filled in 1897, and Oates campaigned for it, but without success. The position was given to Edmund W. Pettus, a supporter of free silver. The combative Oates, a Bourbon of great value to the Democrats when political confrontation was necessary, was no longer so useful.

William Calvin Oates and Men, 1898

Despite this victory, Oates’s Democratic allies suffered setbacks. The Silverites were still a strong faction, and Oates could not prevent Johnson, the pro-silver candidate, from winning the Democratic gubernatorial nomination. With his term drawing to an end, Oates still dreamed of a U.S. Senate seat. A vacancy was due to be filled in 1897, and Oates campaigned for it, but without success. The position was given to Edmund W. Pettus, a supporter of free silver. The combative Oates, a Bourbon of great value to the Democrats when political confrontation was necessary, was no longer so useful.

Upon leaving office, Oates returned to his legal practice. In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, he served as brigadier general of volunteers in a company stationed at Camp Meade, Pennsylvania. He also played a role in Alabama’s “disfranchisement” Convention of 1901, criticizing some of the measures introduced—particularly the “grandfather clause,” an exemption for men whose grandfathers had served in the military. He thought that such provisions were too openly based on racial factors and might be found unconstitutional. He added, characteristically, that not all of the Confederate grandfathers in question had served honorably. Nevertheless, the former governor strongly supported ratification of the 1901 Constitution and the disfranchisement of nearly all African Americans and many poor whites.

Thereafter, Oates applied himself increasingly to Confederate reunions and to writing a well-received account of the war, The War Between the Union and the Confederacy (1905). Having settled in Montgomery, he died on September 9, 1910, and was buried in the city’s Oakwood Cemetery.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Perry, Mark. Conceived in Liberty: Joshua Chamberlain, William Oates, and the American Civil War. New York: Penguin, 1997.

- Rogers, William Warren. The One-Gallused Rebellion: Agrarianism in Alabama, 1865-1896. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1970.

- Sparkman, John. “The Kolb-Oates Campaign of 1894,” M.A. thesis, University of Alabama, 1924.