Alabama Equal Suffrage Association

Votes for Women

The Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) was founded in Birmingham in 1912 with the goal of gaining the right to vote for white women in the state. At its inception, the organization consisted of members of the Birmingham Equal Suffrage Association (BESA) and the Selma Equal Suffrage Association (SESA) and included 350 white, upper-class men and women from Birmingham and 80 from Selma, as well as individuals from Montgomery, Auburn, and Marion.

Votes for Women

The Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) was founded in Birmingham in 1912 with the goal of gaining the right to vote for white women in the state. At its inception, the organization consisted of members of the Birmingham Equal Suffrage Association (BESA) and the Selma Equal Suffrage Association (SESA) and included 350 white, upper-class men and women from Birmingham and 80 from Selma, as well as individuals from Montgomery, Auburn, and Marion.

The cause of suffrage (the civil right to vote) in Alabama began in 1892 with the formation of a group in Decatur. That same year, temperance and suffrage activist Frances Griffin of Wetumpka founded a suffrage group in Chilton County and promoted the cause of women’s voting rights throughout the nation for the rest of the decade. The Alabama Constitutional Convention of 1901 failed to grant any type of suffrage to women, however, and the statewide push for suffrage ceased for a decade. According to the views of the day, women were to be nurturers in the home, and it was considered unnatural to bring them into the realm of politics.

Pattie Ruffner Jacobs

By 1911, there was a revival of interest in woman suffrage in both Birmingham and Selma. In the preceding decade, activist women around the state had been broadening the domestic sphere to include social issues, such as the well-being of children. Many women had also become involved in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) with the goal of eradicating alcohol consumption and the social ills that often resulted from it. The WCTU served as an organizational training ground for future suffragists and revealed to them that without the vote they would not be able to enact true reform.

Pattie Ruffner Jacobs

By 1911, there was a revival of interest in woman suffrage in both Birmingham and Selma. In the preceding decade, activist women around the state had been broadening the domestic sphere to include social issues, such as the well-being of children. Many women had also become involved in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) with the goal of eradicating alcohol consumption and the social ills that often resulted from it. The WCTU served as an organizational training ground for future suffragists and revealed to them that without the vote they would not be able to enact true reform.

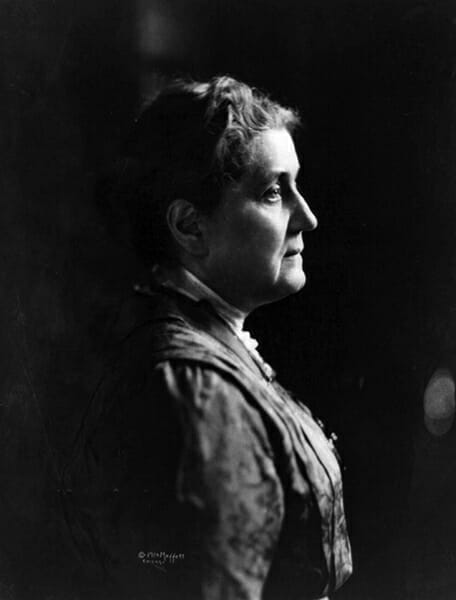

It was in this spirit of social reform that Birmingham activist Pattie Ruffner Jacobs attended a lecture by renowned sociologist and reformer Jane Addams against child labor at a conference in Birmingham in 1911. Addams’s speech revealed to Jacobs that the only way women would be able to accomplish change was through the ballot. Jacobs thus led the effort to create the BESA in 1911.

Jane Addams

Realizing that strength existed in numbers, the members of the BESA invited the members of the SESA, including Selma suffragist (and later state legislator) Hattie Hooker Wilkins, to join together under a unified leadership. In a letter distributed to state newspapers, leaders called for a statewide organization that would be more effective at winning the vote. Thus the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association was formed on October 9, 1912, and allied itself with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Many Southern white women who advocated giving women the right to vote did so at the expense of African American women. They believed that by gaining the vote for white women, they would offset any ballots cast by black men. In no way was the woman suffrage movement in the South designed to give African American women the right to vote. In addition, the AESA initially favored gaining the ballot at the state level, which affirmed the southern belief in the doctrine of states’ rights, whereas NAWSA favored an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Despite the differing views, the AESA sent Jacobs, its newly elected president, to address the NAWSA national convention in November 1912.

Jane Addams

Realizing that strength existed in numbers, the members of the BESA invited the members of the SESA, including Selma suffragist (and later state legislator) Hattie Hooker Wilkins, to join together under a unified leadership. In a letter distributed to state newspapers, leaders called for a statewide organization that would be more effective at winning the vote. Thus the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association was formed on October 9, 1912, and allied itself with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Many Southern white women who advocated giving women the right to vote did so at the expense of African American women. They believed that by gaining the vote for white women, they would offset any ballots cast by black men. In no way was the woman suffrage movement in the South designed to give African American women the right to vote. In addition, the AESA initially favored gaining the ballot at the state level, which affirmed the southern belief in the doctrine of states’ rights, whereas NAWSA favored an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Despite the differing views, the AESA sent Jacobs, its newly elected president, to address the NAWSA national convention in November 1912.

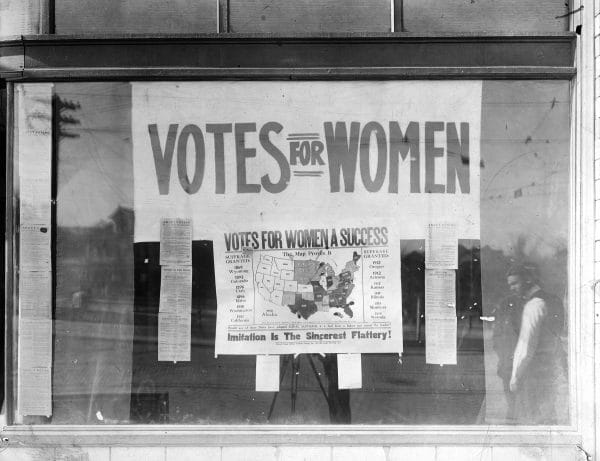

Birmingham Suffrage Headquarters

The AESA opened its headquarters in downtown Birmingham in 1912 and began its outreach to young working women by setting aside a reading room where they could relax and eat lunch during the day. The AESA also established a traveling library, stocked with suffragist literature and pamphlets, to bring its message to interested groups throughout the state. The suffragists initiated “voiceless speech” demonstrations in downtown Birmingham stores in which less-vocal members of the group stood in department store windows and turned the pages of suffrage pamphlets displayed in them. Local chapters placed informational articles in various newspapers, including the Birmingham Age-Herald and the Selma Times, whose business manager, Mary Raiford, sat on the state board and ran a column entitled “Woman Suffrage.”

Birmingham Suffrage Headquarters

The AESA opened its headquarters in downtown Birmingham in 1912 and began its outreach to young working women by setting aside a reading room where they could relax and eat lunch during the day. The AESA also established a traveling library, stocked with suffragist literature and pamphlets, to bring its message to interested groups throughout the state. The suffragists initiated “voiceless speech” demonstrations in downtown Birmingham stores in which less-vocal members of the group stood in department store windows and turned the pages of suffrage pamphlets displayed in them. Local chapters placed informational articles in various newspapers, including the Birmingham Age-Herald and the Selma Times, whose business manager, Mary Raiford, sat on the state board and ran a column entitled “Woman Suffrage.”

BESA Presidents

In January 1913, the AESA held its inaugural state convention at the Hotel Albert in Selma, with seven chapters participating, and its second convention in Huntsville in 1914, with 11 chapters attending. That same year, Bossie O’Brien Hundley of Birmingham became chair of the legislative committee and set to work convincing the Alabama State Legislature to place a woman suffrage amendment on the ballot in the next election. Because women could not vote, they had to depend upon the voting men of Alabama to grant them the right to do so. The Alabama Legislature met every four years, so the AESA members realized that if they were unsuccessful in 1915, they would have to wait until 1919 for another chance. With this in mind, they asked J. H. Greene, a representative from Dallas County, to put forward a suffrage bill in the House. As the bill came up for a vote, however, Greene withdrew support. With a balcony full of suffrage supporters and many legislators wearing yellow suffrage flowers in support of suffrage, the bill to grant women the vote in the state of Alabama by placing an amendment on the next ballot fell 12 votes shy of a three-fifths majority. The AESA and the state of Alabama would have to wait four more years to gain the vote through state action, or wait for the passage of a federal amendment.

BESA Presidents

In January 1913, the AESA held its inaugural state convention at the Hotel Albert in Selma, with seven chapters participating, and its second convention in Huntsville in 1914, with 11 chapters attending. That same year, Bossie O’Brien Hundley of Birmingham became chair of the legislative committee and set to work convincing the Alabama State Legislature to place a woman suffrage amendment on the ballot in the next election. Because women could not vote, they had to depend upon the voting men of Alabama to grant them the right to do so. The Alabama Legislature met every four years, so the AESA members realized that if they were unsuccessful in 1915, they would have to wait until 1919 for another chance. With this in mind, they asked J. H. Greene, a representative from Dallas County, to put forward a suffrage bill in the House. As the bill came up for a vote, however, Greene withdrew support. With a balcony full of suffrage supporters and many legislators wearing yellow suffrage flowers in support of suffrage, the bill to grant women the vote in the state of Alabama by placing an amendment on the next ballot fell 12 votes shy of a three-fifths majority. The AESA and the state of Alabama would have to wait four more years to gain the vote through state action, or wait for the passage of a federal amendment.

Anna Howard Shaw

In 1915 the AESA held its third state convention in Tuscaloosa, with NAWSA president Anna Howard Shaw in attendance. The following year, at the convention in Gadsden, Carrie McCord Parke of Selma was elected president after Jacobs gave up the position to take a seat on the NAWSA board. Jacobs had long believed personally that the only way women in the South would be able to vote would be through a federal amendment. Parke, the new AESA president, moved the group’s headquarters to Selma. When the United States entered World War I, suffragist groups around the country, including the AESA, jumped wholeheartedly into war work, hoping to demonstrate that they deserved the vote through their patriotic contributions to the nation and to a government in which they could not even fully participate.

Anna Howard Shaw

In 1915 the AESA held its third state convention in Tuscaloosa, with NAWSA president Anna Howard Shaw in attendance. The following year, at the convention in Gadsden, Carrie McCord Parke of Selma was elected president after Jacobs gave up the position to take a seat on the NAWSA board. Jacobs had long believed personally that the only way women in the South would be able to vote would be through a federal amendment. Parke, the new AESA president, moved the group’s headquarters to Selma. When the United States entered World War I, suffragist groups around the country, including the AESA, jumped wholeheartedly into war work, hoping to demonstrate that they deserved the vote through their patriotic contributions to the nation and to a government in which they could not even fully participate.

Their work paid off in June 1919, when a federal suffrage amendment was sent to the states for ratification. The AESA led the push to have the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution ratified by the state of Alabama, but their drive failed. They were opposed vehemently by the Women’s Anti-Ratification League, a group formed in 1919 to oppose Alabama’s adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment, with Marie Bankhead Owen (later head of the Alabama Department of Archives and History) serving as the group’s legislative chair. Most state legislators rejected any infringement on their authority from the federal government. Thus in 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the amendment, giving American women the right to vote.

Having achieved suffrage, the AESA members dissolved the organization, and many members joined the League of Women Voters, a national association founded at the 1920 convention of the NASWA. This organization continues to raise awareness of the power women have through the vote and works to ensure that they use the privilege to enact beneficial change.

Further Reading

- Thomas, Mary Martha, ed. Stepping Out of the Shadows: Alabama Women, 1819-1990. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill. New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.