Women's Anti-Ratification League of Alabama

The Women's Anti-Ratification League of Alabama formed on June 17, 1919, in Montgomery, Montgomery County, to block ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which was created to grant women the right to vote in the U.S. Constitution. The organization's position was three-fold: that women's suffrage threatened states' rights, gender roles, and race relations. Ultimately, the group was successful in Alabama, which became the second state to reject the amendment on September 22, 1919. The organization then transformed into the Southern Women's League for the Rejection of the Proposed Susan B. Anthony Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, with the goal of making a "solid South" against women's suffrage.

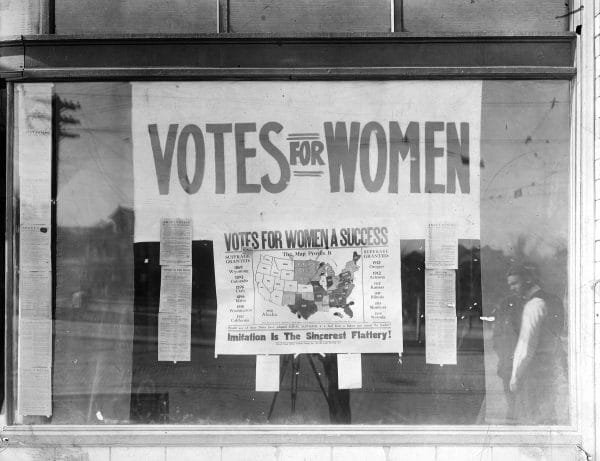

Votes for Women

Although many states had granted women suffrage by the early twentieth century, the effort to amend the Constitution to protect a citizen's right to vote regardless of sex was generally opposed nationally by southern Democrats and almost uniformly by congressional Alabamians. An amendment was proposed by U.S. Senate resolution in 1913 and needed two-thirds of each house to pass but was not approved in the Senate. In the 65th Congress (1917-19), the U.S. House of Representatives approved another resolution 274-136 on January 10, 1918, with all Alabama representatives voting in opposition. Debated extensively from May into October in the Senate, the resolution failed there on October 1, 1918, with both Alabama senators—Oscar Underwood and John Bankhead—voting no. Reintroduced in the 66th Congress (1919-21), the resolution again failed in the Senate on February 10, 1919, but was approved in the House 304-90 on May 21, 1919. Of Alabama's representatives, only William Bacon Oliver of the Sixth District voted in favor of the measure. On June 4, 1919, the Senate approved the resolution 56-25 sending the proposed Nineteenth Amendment to the states. Bankhead and Underwood again opposed it and 15 members abstained from voting. Also that day, the Senate rejected giving states the right to grant women's suffrage, which Bankhead and Underwood favored. The previous day, Underwood voted for a failed measure that would have restricted suffrage to white citizens only. Bankhead was not present, possibly because of illness, and did not vote.

Votes for Women

Although many states had granted women suffrage by the early twentieth century, the effort to amend the Constitution to protect a citizen's right to vote regardless of sex was generally opposed nationally by southern Democrats and almost uniformly by congressional Alabamians. An amendment was proposed by U.S. Senate resolution in 1913 and needed two-thirds of each house to pass but was not approved in the Senate. In the 65th Congress (1917-19), the U.S. House of Representatives approved another resolution 274-136 on January 10, 1918, with all Alabama representatives voting in opposition. Debated extensively from May into October in the Senate, the resolution failed there on October 1, 1918, with both Alabama senators—Oscar Underwood and John Bankhead—voting no. Reintroduced in the 66th Congress (1919-21), the resolution again failed in the Senate on February 10, 1919, but was approved in the House 304-90 on May 21, 1919. Of Alabama's representatives, only William Bacon Oliver of the Sixth District voted in favor of the measure. On June 4, 1919, the Senate approved the resolution 56-25 sending the proposed Nineteenth Amendment to the states. Bankhead and Underwood again opposed it and 15 members abstained from voting. Also that day, the Senate rejected giving states the right to grant women's suffrage, which Bankhead and Underwood favored. The previous day, Underwood voted for a failed measure that would have restricted suffrage to white citizens only. Bankhead was not present, possibly because of illness, and did not vote.

To be officially adopted into the Constitution, the amendment needed to be ratified by three-fourths of the states, which in 1919 meant 36 states. Two weeks after its passage, a group of Montgomery women met at the home of Nina Pinckard, a wealthy and well-connected socialite, and formed the Women's Anti-Ratification League of Alabama to block the amendment's ratification in Alabama. Pinckard was elected president of the League, which also included Alice Henderson, Elizabeth Houston Sheehan, Daisie Thigpen, and Marie Bankhead Owen, daughter of Sen. John Bankhead and the second director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Nina Pinckard

The organization held public meetings to warn women and men on the perceived threats of the Nineteenth Amendment. Its pamphlets, editorials, and fliers outlined the group's arguments that women's suffrage was a threat to states' rights, gender roles, and race relations. In late June, the Anti-Ratification League announced its slogan, "Alabama for Alabamians," indicating that its chief argument was that women's suffrage was a states' rights issue. Some members allegedly supported the notion of women's suffrage but only at the state level. They believed that passing a federal amendment would invite too much oversight into their election processes and take control of the electorate away from the state government. Instead, they insisted that if Alabama women truly wanted the vote, they should continue to seek state legislation that would allow for it.

Nina Pinckard

The organization held public meetings to warn women and men on the perceived threats of the Nineteenth Amendment. Its pamphlets, editorials, and fliers outlined the group's arguments that women's suffrage was a threat to states' rights, gender roles, and race relations. In late June, the Anti-Ratification League announced its slogan, "Alabama for Alabamians," indicating that its chief argument was that women's suffrage was a states' rights issue. Some members allegedly supported the notion of women's suffrage but only at the state level. They believed that passing a federal amendment would invite too much oversight into their election processes and take control of the electorate away from the state government. Instead, they insisted that if Alabama women truly wanted the vote, they should continue to seek state legislation that would allow for it.

While some League members supported women's suffrage at the state level, others detested it outright. One of their chief arguments against the idea of women's suffrage was that it went against the prevailing idealized view of "womanhood." At the time, many believed that a woman's place was in the home, overseeing a sphere of domestic retreat for husbands to return to after a day at work. They argued that politics was a male-dominated activity because men were built for its tough atmosphere, whereas women were too delicate by nature to participate in the brutish arena of political struggle.

Furthermore, antisuffragists feared that once women received the vote, they would then pursue other privileges, like working outside of the home or running for political office. In their pamphlets, they warned that this would lead to a reverse in gender roles, force men to stay home, and threaten the very fabric of family life. This gendered argument made women's suffrage at any level appear dangerous and unnatural.

As a universally all-white organization, arguably the League's most important motivation was maintaining white supremacy. In an article about the Anti-Ratification League for Alabama for the New York World in October of 1919, the leaders revealed that their impetus for forming had little to do with woman's unfitness for the ballot or the states' rights issues with a federal amendment, but more with the "race problem" in the South. Alabama's 1901 Constitution established strict voting regulations that disenfranchised most of the state's African American male population. The League feared that the Nineteenth Amendment would reopen the question of Black suffrage by making it possible for African American women to vote and inviting the federal government into their election laws. They believed this would lead to discontent between the races and ultimately to a "race war."

Pattie Ruffner Jacobs

On July 16, 1919, the Alabama legislature hosted a joint session for a debate on the amendment. Both suffragists and antisuffragists were given 90 minutes to argue their point of view. The suffragists lined up eight speakers, from prominent Alabama suffragist Pattie Ruffner Jacobs of the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association to Alabama Supreme Court chief justice John C. Anderson, to outline their arguments for ratification. When it was time for the antisuffragists to speak, they refused. Instead, they submitted a memorial speech with their arguments. It was read aloud by Hale County state senator J. B. Evins and Dale County senator and future U.S. representative Archibald Hill Carmichael. The speech outlined the three main arguments of states' rights, gender, and race, and proved successful as it was a concise speech that could easily be reprinted in newspapers the following day. The Anti-Ratification League proved successful in Alabama, when on September 22, 1919, it became the second state to reject the amendment.

Pattie Ruffner Jacobs

On July 16, 1919, the Alabama legislature hosted a joint session for a debate on the amendment. Both suffragists and antisuffragists were given 90 minutes to argue their point of view. The suffragists lined up eight speakers, from prominent Alabama suffragist Pattie Ruffner Jacobs of the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association to Alabama Supreme Court chief justice John C. Anderson, to outline their arguments for ratification. When it was time for the antisuffragists to speak, they refused. Instead, they submitted a memorial speech with their arguments. It was read aloud by Hale County state senator J. B. Evins and Dale County senator and future U.S. representative Archibald Hill Carmichael. The speech outlined the three main arguments of states' rights, gender, and race, and proved successful as it was a concise speech that could easily be reprinted in newspapers the following day. The Anti-Ratification League proved successful in Alabama, when on September 22, 1919, it became the second state to reject the amendment.

After their victory in Alabama, League members, especially Nina Pinckard, wanted to organize a "solid South" against the Nineteenth Amendment. And so they rebranded the organization as the Southern Women's League for the Rejection of the Proposed Susan B. Anthony Amendment of the United States Constitution. This regional organization was headquartered in Montgomery, and Pinckard became its president. She sought to create local chapters in other southern states and travelled to help bolster their anti-suffrage efforts. Her final trip was to Nashville, Tennessee, in the summer of 1920, when she worked tirelessly to block the amendment. Her attempt failed, and Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the amendment. On August 26, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment was officially adopted into the Constitution. Pinckard tried to overturn the decision in the courts, and antisuffragists threatened to mobilize support against those politicians who had voted for the measure. Nevertheless, many of the antisuffragists registered to vote and folded their work into other causes. Alabama did not ratify the amendment until September 8, 1953.

Further Reading

- Thomas, Mary Martha, ed.. Stepping Out of the Shadows: Alabama Women, 1819-1990. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill. New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.