Know-Nothing Party

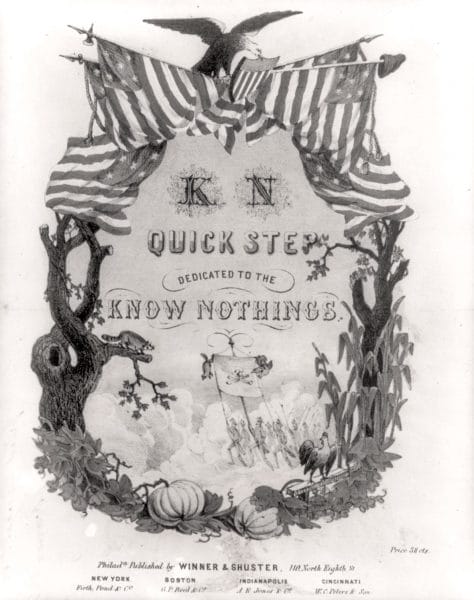

Know-Nothing Party Sheet Music

The Know-Nothing Party, also known as the American Party, formed in Alabama in the 1850s, briefly attracted converts from the Whig and Democratic parties, and split apart just before the Civil War. This short-lived coalition came together over the issues of slavery, states’ rights, immigration, and anti-Catholicism. A Democratic Party backlash overwhelmed any political successes gained by the Know-Nothings, and the party gradually dissolved. Most of its members became Democrats, some eventually became Republicans, and others abandoned politics altogether.

Know-Nothing Party Sheet Music

The Know-Nothing Party, also known as the American Party, formed in Alabama in the 1850s, briefly attracted converts from the Whig and Democratic parties, and split apart just before the Civil War. This short-lived coalition came together over the issues of slavery, states’ rights, immigration, and anti-Catholicism. A Democratic Party backlash overwhelmed any political successes gained by the Know-Nothings, and the party gradually dissolved. Most of its members became Democrats, some eventually became Republicans, and others abandoned politics altogether.

During the late 1840s and 1850s, a series of important realignments reshaped the American political landscape. The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, in conjunction with other factors, permanently fractured the national Whig party. Northern Whigs moved increasingly toward abolitionism and resistance to extending slavery into new territories and hoped to use provisions of the new legislation to prevent slave-owning in Kansas. Southern Whigs, overwhelmingly Unionist in 1854, hoped to achieve the opposite result. Unable to withstand the mounting factional pressures over slavery and abolition and with flagging support from the national party, Alabama’s Whig Party disintegrated, as it did across the South. The splintering Whigs in Alabama faced three choices as they considered their political future. They could join their traditional opponents, the Democrats, reform the party under their old banner despite inconsistencies with the northern branch, or launch a new party.

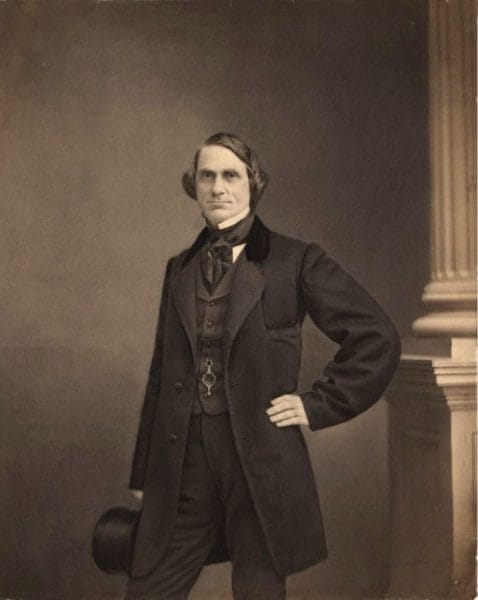

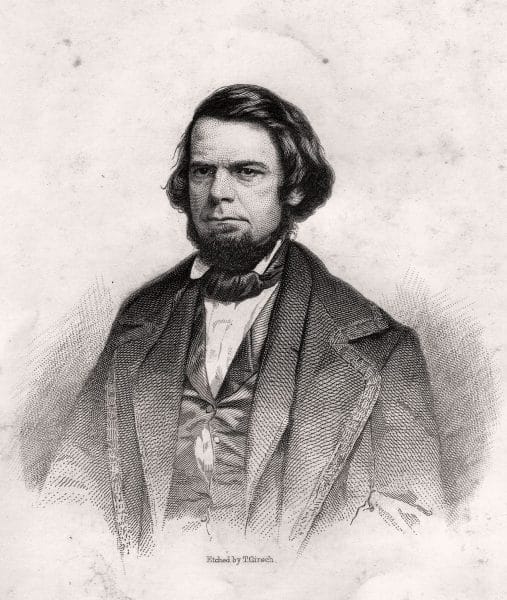

Henry W. Hilliard

In the North, the Know-Nothings espoused a “nativist” political platform and focused their ire on two groups: immigrants and Catholics. Alabama, however, had few immigrants or Catholics. The 1850 Census identified only 7,509 foreign-born residents—mostly in Mobile—out of a total of population of 428,779 whites and free Blacks, and the state had only five Catholic churches. Thus Alabama’s former Whigs, like Henry Hilliard, Daniel Pratt, and Johnson J. Hooper, tended to join with the Know-Nothings for their emphasis on internal state improvements in infrastructure and industry. Industrialists like Pratt had long advocated state aid for railroads, but they had experienced only limited success in achieving such legislation.

Henry W. Hilliard

In the North, the Know-Nothings espoused a “nativist” political platform and focused their ire on two groups: immigrants and Catholics. Alabama, however, had few immigrants or Catholics. The 1850 Census identified only 7,509 foreign-born residents—mostly in Mobile—out of a total of population of 428,779 whites and free Blacks, and the state had only five Catholic churches. Thus Alabama’s former Whigs, like Henry Hilliard, Daniel Pratt, and Johnson J. Hooper, tended to join with the Know-Nothings for their emphasis on internal state improvements in infrastructure and industry. Industrialists like Pratt had long advocated state aid for railroads, but they had experienced only limited success in achieving such legislation.

It was hardly surprising that Alabama’s Whigs were attracted to the Know-Nothings, but more unexpected was the conversion of many of the state’s Democrats. Party conflict between Whigs and Democrats was fierce enough to prevent much party-swapping. But for a variety of reasons, the Know-Nothings were able to attract prominent Democrats such as Percy Walker, William Russell Smith, Jeremiah Clemens, Robert Baker, and George Shortbridge. Some were attracted by the Know-Nothing party’s secrecy provisions and fraternalism, which included a fairly intricate system of oaths, handshakes, and passwords. Other Democrats were frustrated by their party’s seniority system and left for the chance to become rising stars in the new political order.

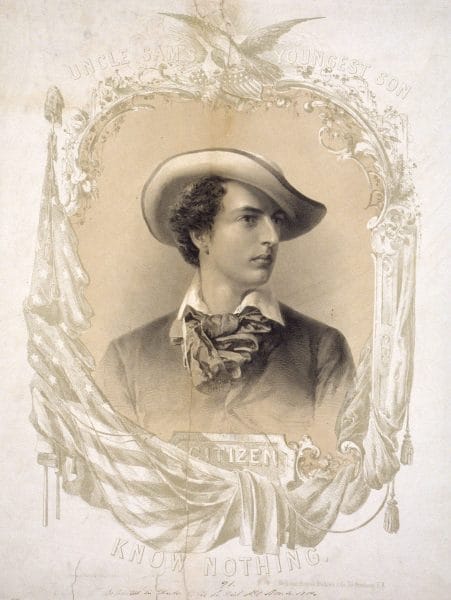

Know-Nothing Party Advertisement

In addition to attracting converts, the Know-Nothings also developed other trappings of highly organized, modern political parties, including caucuses, rallies, conventions, and formal platforms. On June 12, 1855, the Know-Nothings held a state convention in Montgomery and nominated Shortbridge for governor. The party platform included nativist planks aimed at linking the state party with the national party and southern rights provisions that protected slavery. Regarding the growing issue of secession, Know-Nothings tended to have more Unionist sympathies than some of the more zealous Democrats. Know-Nothing nominees for other posts indicate that the party was highly organized, perhaps further explaining the number of Democratic defections. Three of the five congressional candidates were former Democrats, and state-aid supporters ran in former Whig strongholds. Know-Nothing newspapers boasted of Democrats joining the new party, and Democratic newspapers showed concern at the vigorous campaigning of their new rivals. The Know-Nothings became the largest and most significant threat to Alabama Democrats in years.

Know-Nothing Party Advertisement

In addition to attracting converts, the Know-Nothings also developed other trappings of highly organized, modern political parties, including caucuses, rallies, conventions, and formal platforms. On June 12, 1855, the Know-Nothings held a state convention in Montgomery and nominated Shortbridge for governor. The party platform included nativist planks aimed at linking the state party with the national party and southern rights provisions that protected slavery. Regarding the growing issue of secession, Know-Nothings tended to have more Unionist sympathies than some of the more zealous Democrats. Know-Nothing nominees for other posts indicate that the party was highly organized, perhaps further explaining the number of Democratic defections. Three of the five congressional candidates were former Democrats, and state-aid supporters ran in former Whig strongholds. Know-Nothing newspapers boasted of Democrats joining the new party, and Democratic newspapers showed concern at the vigorous campaigning of their new rivals. The Know-Nothings became the largest and most significant threat to Alabama Democrats in years.

William Russell Smith

Given the secrecy of many members, it is difficult to quantify the number of ordinary Alabamians who became Know-Nothings or assess their common socioeconomic characteristics. Just the same, however, many Democrats were convinced that the Know-Nothings were a significant threat. Realizing their political leadership was at stake, Alabama Democrats responded with a vengeance. Ardent slavery and states’ rights advocate William Lowndes Yancey and others declared Know-Nothings unable to protect the institution. Yancey and other Alabama Democrats reasoned that the state’s Know-Nothings were destined to be nothing more than a small faction of a national party that contained too many abolitionists. The Montgomery Advertiser, a Democratic newspaper, referred to Know-Nothings as “fanatics and abominable treasoners,” and Democrats accused Daniel Pratt, who ran as a Know-Nothing candidate for state Senate, of secretly plotting to enact taxes in order to raise money for railroad construction. By the middle of the 1855 campaign, the Democrats’ negative attacks had worked. The Know-Nothings, so promising as a political force that spring, were soundly beaten at the ballot box. In the 1855 election, Alabama voters elected a Democratic governor, five Democrats and two Know-Nothings to Congress, 61 Democrats and 39 Know-Nothings to the state House of Representatives, and 20 Democrats and 13 Know-Nothings to the state Senate. Two years later, the party ran three candidates for Congress, all unsuccessfully. By 1859, the Know-Nothings were virtually extinct, killed by state and sectional issues and political realignments. The national party died a similar death as northern Know-Nothings transitioned to the Republican Party with a few becoming Democrats.

William Russell Smith

Given the secrecy of many members, it is difficult to quantify the number of ordinary Alabamians who became Know-Nothings or assess their common socioeconomic characteristics. Just the same, however, many Democrats were convinced that the Know-Nothings were a significant threat. Realizing their political leadership was at stake, Alabama Democrats responded with a vengeance. Ardent slavery and states’ rights advocate William Lowndes Yancey and others declared Know-Nothings unable to protect the institution. Yancey and other Alabama Democrats reasoned that the state’s Know-Nothings were destined to be nothing more than a small faction of a national party that contained too many abolitionists. The Montgomery Advertiser, a Democratic newspaper, referred to Know-Nothings as “fanatics and abominable treasoners,” and Democrats accused Daniel Pratt, who ran as a Know-Nothing candidate for state Senate, of secretly plotting to enact taxes in order to raise money for railroad construction. By the middle of the 1855 campaign, the Democrats’ negative attacks had worked. The Know-Nothings, so promising as a political force that spring, were soundly beaten at the ballot box. In the 1855 election, Alabama voters elected a Democratic governor, five Democrats and two Know-Nothings to Congress, 61 Democrats and 39 Know-Nothings to the state House of Representatives, and 20 Democrats and 13 Know-Nothings to the state Senate. Two years later, the party ran three candidates for Congress, all unsuccessfully. By 1859, the Know-Nothings were virtually extinct, killed by state and sectional issues and political realignments. The national party died a similar death as northern Know-Nothings transitioned to the Republican Party with a few becoming Democrats.

Further Reading

- Dorman, Lewy. Party Politics in Alabama from 1850 through 1860. 1935. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Frederick, Jeff. “Unintended Consequences: The Rise and Fall of the Know-Nothing Party in Alabama.” Alabama Review (January 2002): 3–33.

- Thornton, J. Mills, III. Politics and Power in a Slave Society. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.