CSS Alabama

CSS Alabama

Built in England and manned by an English crew with Confederate officers, the CSS Alabama was the most successful and notorious Confederate raiding vessel of the Civil War. Between the summer of 1862 and the spring of 1864, the Alabama captured 65 vessels flying the U.S. flag and sank one Union warship. The Alabama was a media sensation and spread panic throughout the pro-Union merchant fleet and distracted part of the U.S. Navy from the essential duty of blockading southern ports. The Alabama’s most important role in the conflict, however, was as a brief morale booster for the failing Confederate cause.

CSS Alabama

Built in England and manned by an English crew with Confederate officers, the CSS Alabama was the most successful and notorious Confederate raiding vessel of the Civil War. Between the summer of 1862 and the spring of 1864, the Alabama captured 65 vessels flying the U.S. flag and sank one Union warship. The Alabama was a media sensation and spread panic throughout the pro-Union merchant fleet and distracted part of the U.S. Navy from the essential duty of blockading southern ports. The Alabama’s most important role in the conflict, however, was as a brief morale booster for the failing Confederate cause.

In 1862, the Confederate government contracted with the Laird Brothers shipyard at Birkenhead in the United Kingdom, across the Mersey River from Liverpool, to build cruisers capable of running down merchant ships. The ship that would become the CSS Alabama, known only as “290” during construction, was 220 feet long and just under 32 feet wide and was equipped for both wind and steam power. Its retractable propeller made for faster sailing without engine assistance, thus conserving coal, and a collapsible smokestack allowed the ship to assume the guise of a purely wind-driven vessel.

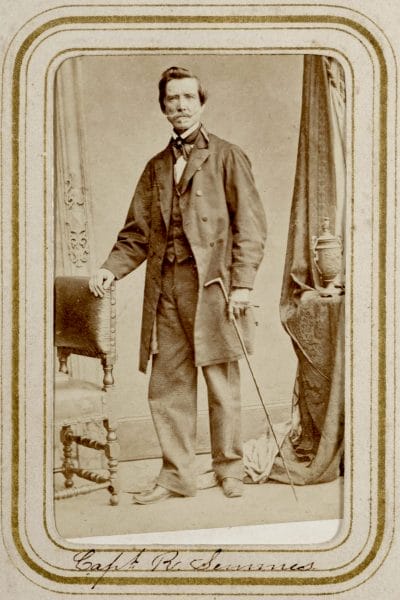

Raphael Semmes

To avoid violating British neutrality, the Confederate Navy came up with a plan to send the completed but unarmed ship to the Azore Islands, midway between Europe and North America. There, the Alabama’s commander, Capt. Raphael Semmes, of Charles County, Maryland, would meet the ship with the necessary armaments. On July 29, the “290” slipped out of Birkenhead under the command of a British merchant captain and headed for the Azores. Once there, Semmes took command, commissioned the ship as the Alabama, and took aboard six naval guns, including two large-caliber pivots mounted on revolving tracks. Semmes brought with him a cadre of Confederate officers and filled out his temporary British crew with sailors tempted by promises of gold and prize money for captured vessels.

Raphael Semmes

To avoid violating British neutrality, the Confederate Navy came up with a plan to send the completed but unarmed ship to the Azore Islands, midway between Europe and North America. There, the Alabama’s commander, Capt. Raphael Semmes, of Charles County, Maryland, would meet the ship with the necessary armaments. On July 29, the “290” slipped out of Birkenhead under the command of a British merchant captain and headed for the Azores. Once there, Semmes took command, commissioned the ship as the Alabama, and took aboard six naval guns, including two large-caliber pivots mounted on revolving tracks. Semmes brought with him a cadre of Confederate officers and filled out his temporary British crew with sailors tempted by promises of gold and prize money for captured vessels.

The Alabama embarked on its voyage on August 24, taking a whaling ship out of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, as its first prize on September 5. During the next two weeks, Semmes preyed on the American whaling fleet, making prisoners of the crews and burning most of the vessels after relieving them of supplies. Occasionally, he released a ship on bond and required it to give passage to his prisoners. Southern and foreign sailors among his captives frequently augmented the Alabama’s skeleton crew, and Semmes soon had close to the full complement of 150 men.

CSS Alabama Sinking the USS Hatteras

The Alabama next headed toward the eastern coast of the United States, survived a nearly disastrous hurricane, and captured a dozen trading vessels along the way. By mid-autumn the name Alabama had begun to terrify Union-based ship owners. Abandoning plans for a raid along the coast of New York and New England, Semmes turned his ship toward the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Ten days after the Confederacy secured a New Year’s Day victory at Galveston, Texas, the Alabama arrived offshore and lured the USS Hatteras to sea by posing as a Confederate blockade runner, a supply ship designed to get past enemy ships. The Hatteras, a ferryboat converted into an ungainly gunboat, caught up with the Alabama after dark, and Semmes continued the ruse when hailed, identifying his ship as a British vessel until a moment before delivering a devastating volley of cannon fire at point-blank range. After a brief exchange, the Hatteras sank quickly in shallow water, and the Alabama sailed for Jamaica with the downed ship’s dazed survivors aboard. After Jamaica, the Alabama returned to the mid-Atlantic and headed south toward Brazil, racking up another score of enemy captures along the way. In summer 1863, Semmes headed toward Cape Town, South Africa, where he armed a captured vessel and christened it the CSS Tuscaloosa.

CSS Alabama Sinking the USS Hatteras

The Alabama next headed toward the eastern coast of the United States, survived a nearly disastrous hurricane, and captured a dozen trading vessels along the way. By mid-autumn the name Alabama had begun to terrify Union-based ship owners. Abandoning plans for a raid along the coast of New York and New England, Semmes turned his ship toward the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Ten days after the Confederacy secured a New Year’s Day victory at Galveston, Texas, the Alabama arrived offshore and lured the USS Hatteras to sea by posing as a Confederate blockade runner, a supply ship designed to get past enemy ships. The Hatteras, a ferryboat converted into an ungainly gunboat, caught up with the Alabama after dark, and Semmes continued the ruse when hailed, identifying his ship as a British vessel until a moment before delivering a devastating volley of cannon fire at point-blank range. After a brief exchange, the Hatteras sank quickly in shallow water, and the Alabama sailed for Jamaica with the downed ship’s dazed survivors aboard. After Jamaica, the Alabama returned to the mid-Atlantic and headed south toward Brazil, racking up another score of enemy captures along the way. In summer 1863, Semmes headed toward Cape Town, South Africa, where he armed a captured vessel and christened it the CSS Tuscaloosa.

In fall 1863, the Alabama sailed east to the Indian Ocean, where a cyclone again nearly sent her to the bottom. By then, the Alabama’s success had persuaded many Union-based ship owners to register their vessels under foreign flags, and in the East Indies Semmes captured only half a dozen ships. Early in December, the Alabama put in at Pulo Condore, an island now belonging to Vietnam, and the crew made temporary repairs to the ship’s filthy and deteriorating hull. They had grown surly and mutinous during the long voyage, and when the ship departed Pulo Condore after Christmas, Semmes stayed out at sea to prevent desertion. His officers began wearing sidearms on deck.

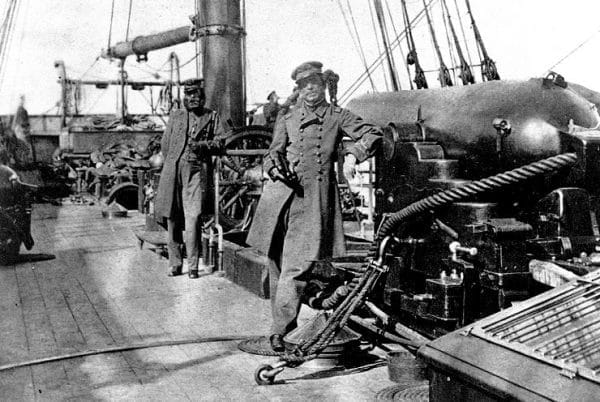

Raphael Semmes on the CSS Alabama

What would be the last leg of the Alabama’s journey took nearly six months and encompassed almost 20,000 miles, with only a few scattered prizes to show for it. In spring 1864, Semmes made the decision to take the Alabama to the drydocks of Cherbourg, France, where his men could make much-needed repairs to the ship. When the Alabama made port on June 11, 1864, the ship and her crew were worn out. Their faith in the Confederacy had also been shaken by recent defeats in battles such as Vicksburg and Gettysburg. And their mood was not lifted by the arrival of the Union navy’s USS Kearsarge, a military steam frigate slightly superior to the Alabama in armament that had sailed from the Netherlands and anchored off Cherbourg harbor.

Raphael Semmes on the CSS Alabama

What would be the last leg of the Alabama’s journey took nearly six months and encompassed almost 20,000 miles, with only a few scattered prizes to show for it. In spring 1864, Semmes made the decision to take the Alabama to the drydocks of Cherbourg, France, where his men could make much-needed repairs to the ship. When the Alabama made port on June 11, 1864, the ship and her crew were worn out. Their faith in the Confederacy had also been shaken by recent defeats in battles such as Vicksburg and Gettysburg. And their mood was not lifted by the arrival of the Union navy’s USS Kearsarge, a military steam frigate slightly superior to the Alabama in armament that had sailed from the Netherlands and anchored off Cherbourg harbor.

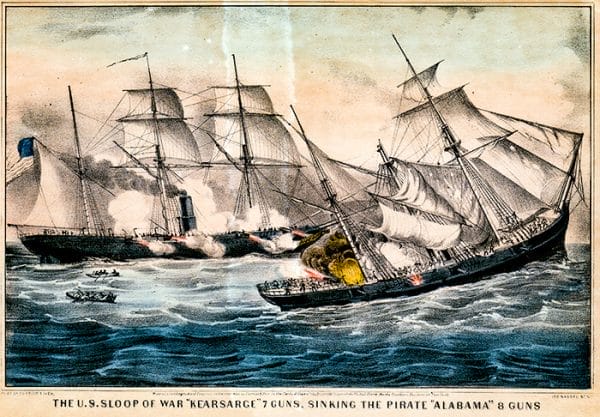

Sinking of the CSS Alabama

Semmes recognized that he could not outrun the better-maintained Kearsarge and that his ship would be useless to the Confederacy bottled up in the harbor, so he took the Alabama out to fight on June 19. For an hour, the two vessels circled each other in the English Channel, and then Alabama scored a potentially victorious shot by lodging a large unexploded shell in the Kearsarge’s sternpost, impeding operation of the rudder. The ship was still able to steer with extra hands at the helm, however, and Alabama’s luck ended there. The well-schooled gunners on the Kearsarge slaughtered the Confederate gunners and riddled the Alabama with shot and shell, and Semmes was forced to head toward the coast in the hope of making a landing. Too damaged by the encounter, the Alabama went down outside French national waters. At least 28 of the 146 officers and crew died in the action, and the Kearsarge captured 68 more, but Semmes and most of his officers were rescued from the water by a British yacht and brought to Southampton, England.

Sinking of the CSS Alabama

Semmes recognized that he could not outrun the better-maintained Kearsarge and that his ship would be useless to the Confederacy bottled up in the harbor, so he took the Alabama out to fight on June 19. For an hour, the two vessels circled each other in the English Channel, and then Alabama scored a potentially victorious shot by lodging a large unexploded shell in the Kearsarge’s sternpost, impeding operation of the rudder. The ship was still able to steer with extra hands at the helm, however, and Alabama’s luck ended there. The well-schooled gunners on the Kearsarge slaughtered the Confederate gunners and riddled the Alabama with shot and shell, and Semmes was forced to head toward the coast in the hope of making a landing. Too damaged by the encounter, the Alabama went down outside French national waters. At least 28 of the 146 officers and crew died in the action, and the Kearsarge captured 68 more, but Semmes and most of his officers were rescued from the water by a British yacht and brought to Southampton, England.

The Alabama initiated a trend toward foreign ship registration and encouraged the diversion of Union naval power, but the principal effect of the ship’s legendary exploits, made famous in the world press, was to bolster southern morale. The tension that the Alabama and other raiders caused between the U.S. and British governments, however, counterbalanced that benefit, ultimately cooling sympathy for the Confederacy in Great Britain, perhaps the only foreign nation that might have effectively intervened on its behalf. Indeed, the British government later had to pay $15,000,000 in claims to ship owners whose property was destroyed by the Alabama and other Confederate cruisers.

CSS Alabama Fire Hose Nozzle

The wreck of the Alabama was discovered in 1984 seven miles out from Cherbourg by the French minesweeper Circe. In 1988, the Association CSS Alabama was founded in France to oversee mapping and archaeological investigation of the wreck site. The ship’s Blakely gun was recovered in 1994 and was found to be still loaded. In 1999, a second organization, the CSS Alabama Association, was founded in the United States to help raise funds and otherwise support the French organization. In 2002, several hundred artifacts, including the ship’s bell, were recovered from the site by the Naval History and Heritage Command of the U.S. Navy. The artifacts are currently housed at the Washington Navy Yard in Washington, D.C.

CSS Alabama Fire Hose Nozzle

The wreck of the Alabama was discovered in 1984 seven miles out from Cherbourg by the French minesweeper Circe. In 1988, the Association CSS Alabama was founded in France to oversee mapping and archaeological investigation of the wreck site. The ship’s Blakely gun was recovered in 1994 and was found to be still loaded. In 1999, a second organization, the CSS Alabama Association, was founded in the United States to help raise funds and otherwise support the French organization. In 2002, several hundred artifacts, including the ship’s bell, were recovered from the site by the Naval History and Heritage Command of the U.S. Navy. The artifacts are currently housed at the Washington Navy Yard in Washington, D.C.

Further Reading

- Marvel, William. The Alabama and the Kearsarge: The Sailor’s War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Merli, Frank J. Great Britain and the Confederate Navy, 1861-1865. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Semmes, Raphael. Memoirs of Service Afloat During the War Between the States. 1869. Reprint, Secaucus, N.J.: Blue & Grey Press, 1987.