Louvin Brothers

Louvin Brothers

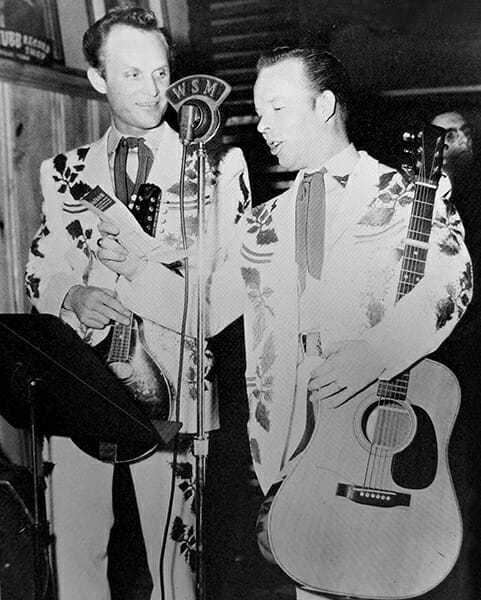

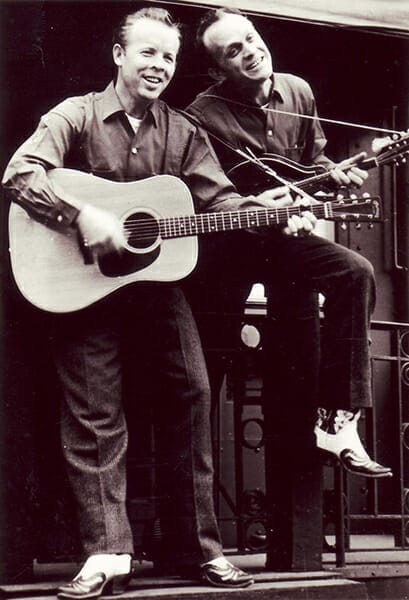

Charlie (1927-2011) and Ira (1924-1965) Loudermilk, better known as the Louvin Brothers, formed a key transitional country music duo in the 1950s. In both their lyrical and musical approach, the Louvins helped forge a link between country music’s rustic roots and its movement toward urban sophistication in the wake of the rock and roll era. Although the Louvins embraced musical innovation, their lyrics reflected an affinity for country music and southern rural traditions that were under assault during the large-scale urbanization of the post-World War II period. They created some of the most impressive country music of the 1950s, influencing young singers in both the country and popular music veins with their intricate harmonies and dextrous musicianship.

Louvin Brothers

Charlie (1927-2011) and Ira (1924-1965) Loudermilk, better known as the Louvin Brothers, formed a key transitional country music duo in the 1950s. In both their lyrical and musical approach, the Louvins helped forge a link between country music’s rustic roots and its movement toward urban sophistication in the wake of the rock and roll era. Although the Louvins embraced musical innovation, their lyrics reflected an affinity for country music and southern rural traditions that were under assault during the large-scale urbanization of the post-World War II period. They created some of the most impressive country music of the 1950s, influencing young singers in both the country and popular music veins with their intricate harmonies and dextrous musicianship.

Ira and Charlie Louvin were two of seven children born to Colonel Monero and Georgianne (né Wooten) Loudermilk. After World War I, the couple moved from North Carolina to the Sand Mountain region of northern Alabama where Ira was born on April 21, 1924, and Charlie on July 7, 1927. In 1929, the family relocated to Henagar, at the northeast end of the mountain in DeKalb County, where they raised cotton, sugar cane, and vegetables on 23 acres of land. Like most families in the area at that time, the Loudermilks grew up without electricity, mechanically powered farm equipment, and other modern conveniences.

Louvin Brothers

Both parents provided Ira and Charlie with exposure to music throughout their childhood. Their father played banjo and fiddle, and their mother sang traditional sentimental songs around the house. Their mother’s family participated in the Sacred Harp style of church singing, and in general, their involvement in their church exposed the young brothers to hymns and other religious material. Through their father’s record collection, the brothers became familiar with the songs of Uncle Dave Macon, Roy Acuff, the Delmore Brothers, and the Blue Sky Boys. Additionally, from listening to the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday nights, they heard many of the other major country music acts of the 1930s. Influenced primarily by Bill Monroe, Ira procured his first mandolin at the age of 19, giving the guitar he had been playing up to that time to Charlie. As the duo gained more confidence in their performing abilities, they started playing together occasionally in public and began toying with the idea of making a career out of performing.

Louvin Brothers

Both parents provided Ira and Charlie with exposure to music throughout their childhood. Their father played banjo and fiddle, and their mother sang traditional sentimental songs around the house. Their mother’s family participated in the Sacred Harp style of church singing, and in general, their involvement in their church exposed the young brothers to hymns and other religious material. Through their father’s record collection, the brothers became familiar with the songs of Uncle Dave Macon, Roy Acuff, the Delmore Brothers, and the Blue Sky Boys. Additionally, from listening to the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday nights, they heard many of the other major country music acts of the 1930s. Influenced primarily by Bill Monroe, Ira procured his first mandolin at the age of 19, giving the guitar he had been playing up to that time to Charlie. As the duo gained more confidence in their performing abilities, they started playing together occasionally in public and began toying with the idea of making a career out of performing.

A series of events postponed the brothers’ plans for singing together professionally, principally the destruction by fire of the Loudermilks’ home in 1938 and Ira’s marriage (his first of four) and subsequent birth of his daughter. Ira supported his family by working in a Chattanooga cotton mill, but he returned to northern Alabama frequently to write songs, rehearse, and perform occasionally with Charlie at local functions. In late 1942, the brothers began appearing on radio station WDEF in Chattanooga and performing throughout the area, even as Ira continued working at the mill. In 1945, Charlie joined the U.S. Army and Ira moved to Knoxville, working a series of odd jobs and performing with Charlie Monroe’s band. When Charlie was discharged in 1946, Ira quit Monroe’s band, and the duo began performing on Knoxville radio. It was around this time that they changed their performing name to the Louvin Brothers in an effort to increase their marketability.

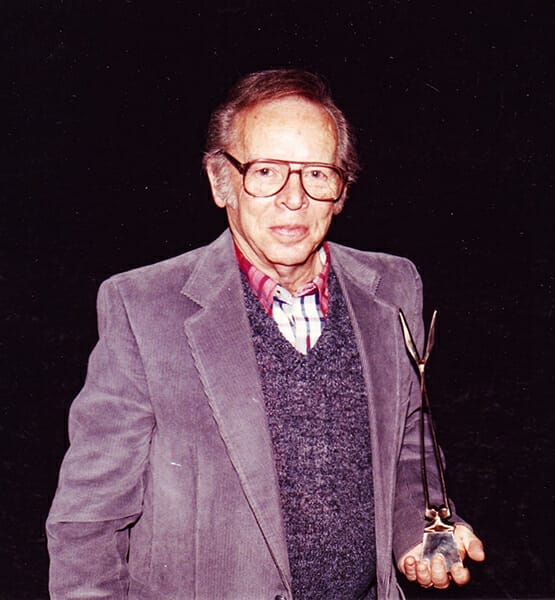

Charlie Louvin

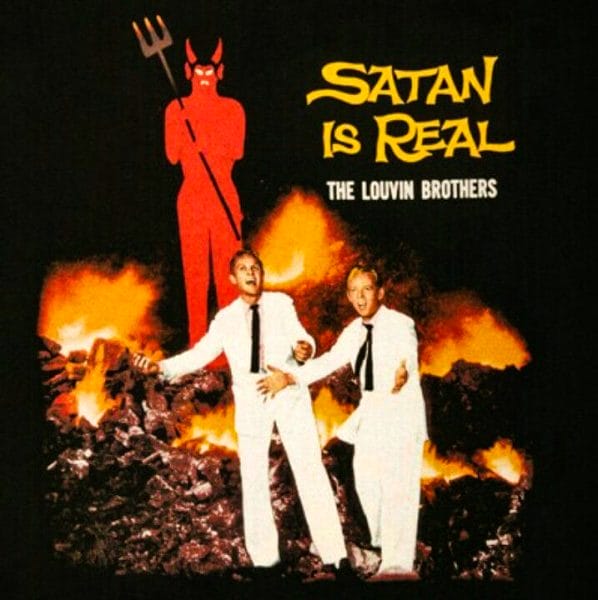

In 1946, the group moved to Memphis, where they remained until 1950 on station WMPS, performing three shows a day and touring the area at night. During this time, the brothers made their first commercial recordings for the Apollo Records label in 1947, including “Alabama,” an evocative tribute to their home state. Their songwriting talents gained the attention of song publisher Fred Rose in Nashville whose affiliation with country stars Roy Acuff and Hank Williams made him a prominent figure on the growing Nashville scene. Rose arranged auditions with Decca Records for the Louvins in 1949 and MGM in 1951. Despite the modest commercial success of their MGM recordings, Rose and the Louvins grew displeased with MGM’s tentative promotion of the group, prompting the brothers to move to Capitol Records in late 1952. The Louvins produced numerous noteworthy gospel recordings that retain their powerful message today, including “The Weapon of Prayer,” “Robe of White,” and “If We Forget God.” They also recorded several topical songs commenting on contemporary events, including “The Great Atomic Power” and “Broad Minded.”

Charlie Louvin

In 1946, the group moved to Memphis, where they remained until 1950 on station WMPS, performing three shows a day and touring the area at night. During this time, the brothers made their first commercial recordings for the Apollo Records label in 1947, including “Alabama,” an evocative tribute to their home state. Their songwriting talents gained the attention of song publisher Fred Rose in Nashville whose affiliation with country stars Roy Acuff and Hank Williams made him a prominent figure on the growing Nashville scene. Rose arranged auditions with Decca Records for the Louvins in 1949 and MGM in 1951. Despite the modest commercial success of their MGM recordings, Rose and the Louvins grew displeased with MGM’s tentative promotion of the group, prompting the brothers to move to Capitol Records in late 1952. The Louvins produced numerous noteworthy gospel recordings that retain their powerful message today, including “The Weapon of Prayer,” “Robe of White,” and “If We Forget God.” They also recorded several topical songs commenting on contemporary events, including “The Great Atomic Power” and “Broad Minded.”

On the verge of commercial success following the release of their early Capitol sides, Charlie was drafted in June 1953 and sent to Korea in December. When he returned home the following year, the brothers resumed recording and touring. In 1955, with “When I Stop Dreaming,” the brothers increasingly turned to more secular material, again with impressive results. Songs such as “Don’t Laugh” and “I Wish It Had Been a Dream” display remarkable harmony and provide an essential link between groups of the 1930s, such as the Blue Sky Boys, and the late 1950s, such as the Everly Brothers. On the strength of their Capitol singles and their reputation as songwriters, producer Ken Nelson landed them a spot on the Grand Ole Opry in February 1955. Although the Louvins had built their reputation as gospel singers, they soon found it to their advantage to give more attention to secular songs. Over the protests of Nelson and their label, the Louvins recorded several nonreligious tunes in May 1955, including “When I Stop Dreaming,” which reached Billboard magazine’s Country Top Ten. Over the course of the next three years, they recorded five more Top 10 hits, including the number-one song “I Don’t Believe You’ve Met My Baby.” They would have ten Top 20 hits in the course of their career.

l

Even as they broke new ground with their singing, musicianship, and songwriting in their secular repertoire, the brothers continued to record potent gospel songs in a modern style, such as “Are You Washed in the Blood?” and “River of Jordan.” In the early 1960s, on tribute albums to the Delmore Brothers and Roy Acuff, the Louvins payed homage to the past while exploring new musical possibilities. On their last recording from 1963, which includes a modern interpretation of “What Would You Do In Exchange for Your Soul” (a song made famous by the Monroe Brothers), the brothers fittingly merge traditional and modern instrumentation in a way that few groups could accomplish successfully.

l

Even as they broke new ground with their singing, musicianship, and songwriting in their secular repertoire, the brothers continued to record potent gospel songs in a modern style, such as “Are You Washed in the Blood?” and “River of Jordan.” In the early 1960s, on tribute albums to the Delmore Brothers and Roy Acuff, the Louvins payed homage to the past while exploring new musical possibilities. On their last recording from 1963, which includes a modern interpretation of “What Would You Do In Exchange for Your Soul” (a song made famous by the Monroe Brothers), the brothers fittingly merge traditional and modern instrumentation in a way that few groups could accomplish successfully.

Competition from rock and roll and mainstream country music acts stymied the Louvins’ success in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but they remained a popular touring act. Conflicts between the brothers (many originating over Ira’s personal problems), however, led Charlie and Ira to disband in late 1963. In June 1965, while returning from a tour of Missouri with some other performers, Ira was killed in an automobile accident, and country music lost one of its finest mandolin players. Charlie went on to a successful solo career that spanned another four decades. He died at his home in Wartrace, Tennessee, on January 26, 2011, after battling pancreatic cancer.

The Louvin Brothers contributed in numerous ways to country music’s evolution from a regional, rural musical style to a national phenomenon in the post-World War II period. Lyrically, they penned some of the finest gospel songs of the 1950s, many speaking to issues brought about by the South’s catapult into modernity and the eclipse of rural traditions that accompanied urbanization and economic progress. Their best secular songs have withstood the test of time and remain as emotionally poignant as they were half a century ago. The Louvins were as adept at writing and singing heart-wrenching songs like “I Wish It Had Been a Dream” as they were with humorous tunes like “Cash on the Barrelhead.” Musically, they provided an essential bridge to modern country music, with instrumentation that at once harkened back to earlier times, reflected contemporary honky-tonk sounds, and pointed ahead to the Nashville Sound. They have received numerous honors, among them their induction into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame (1979), the Alabama Music Hall of Fame (1991) and the Country Music Hall of Fame (2001). As songwriters, singers and musicians, the Louvin Brothers excelled as all-out performers and rightfully remain lauded as country music legends.

Additional Resources

Geno, Suzy Lowry. “Charlie and Ira—The Louvin Brothers.” Bluegrass Unlimited 17 (March 1983): 12-18.

Louvin, Charlie. Interview with Douglas B. Green. November 30, 1977. Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum Oral History Collection, Nashville, Tennessee.

Wolfe, Charles K. In Close Harmony: The Story of the Louvin Brothers. Oxford: University of Mississippi Press, 1996.