Slavery

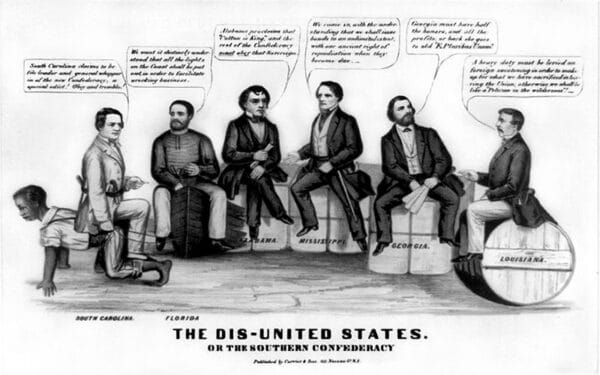

Political Cartoon Depicting Leading Secessionists

Slavery existed in Alabama even before it became a state. Beginning in the territorial period in the early nineteenth century, the institution expanded, coinciding with the development and growth of plantation agriculture. Slavery in the United States was a labor system that depended upon captive Africans who were held by their owners as legal property in a state of permanent bondage. Most enslaved individuals in Alabama were born into enslavement in other states and brought into the area as part of the South’s internal slave trade. Although the living conditions and work required of slaves varied widely across the state, the patterns and variations in Alabama broadly reflected the slave experience elsewhere in the Deep South.

Political Cartoon Depicting Leading Secessionists

Slavery existed in Alabama even before it became a state. Beginning in the territorial period in the early nineteenth century, the institution expanded, coinciding with the development and growth of plantation agriculture. Slavery in the United States was a labor system that depended upon captive Africans who were held by their owners as legal property in a state of permanent bondage. Most enslaved individuals in Alabama were born into enslavement in other states and brought into the area as part of the South’s internal slave trade. Although the living conditions and work required of slaves varied widely across the state, the patterns and variations in Alabama broadly reflected the slave experience elsewhere in the Deep South.

By the antebellum period, Alabama had evolved into a slave society, which is characterized by the proliferation and defense of the institution that shaped much of the state’s economy, politics, and culture. The defense of slavery played a significant role in Alabama’s secession from the Union in 1861. The collapse of the Confederate States of America and the end of the American Civil War (1861-1865) resulted in the emancipation of the state’s enslaved population.

The Development of Slavery in Alabama

As of statehood in 1819, slaves accounted for more than 30 percent of Alabama’s approximately 128,000 inhabitants. The slave population more than doubled during the 1820s and again during the 1830s. When Alabama seceded from the Union in 1861, the state’s 435,080 slaves made up 45 percent of the total population. The largest numbers of slaves were held in bondage in counties located in either the Tennessee River Valley or the Black Belt region. Slavery, however, existed in every county.

Alabama gained statehood during a period when cotton production was spreading throughout the South. Most of Alabama’s antebellum-era settlers originated from areas such as eastern Georgia and western South Carolina. Many of these settlers, who owned slaves before their move to Alabama, came in search of cheap, productive land on which to grow cotton. Many more slaves were brought to Alabama by slave traders, such as those operating in Mobile and Montgomery, where the state’s largest slave auction houses were located. The average slave sold for a few hundred dollars, whereas men between the ages of 17 and 35 who could work in the fields often sold for more than a $1,000. Auctions were themselves traumatic and degrading events, as people being sold were put on display before an audience of white men and sold to the highest bidder.

Labor

Slavery expanded along with commercial agriculture to satisfy shortages of cheap controllable field workers. Slaves on large plantations typically worked in large groups known as gangs, which were supervised by enslaved drivers and white overseers. During the antebellum period, the position of overseer developed into a professional trade dominated by non-slaveholding whites.

The majority of slaves in Alabama, however, labored on modest farms, and the typical Alabama slaveholder owned fewer than five slaves. Slaves often worked alongside and sometimes slept under the same roof as their owner. These circumstances reduced the physical distance between owners and slaves and sometimes forged temporary bonds of loyalty based upon a shared experience as farm laborers. Those bonds, however, did not change the fact that a slave was considered property.

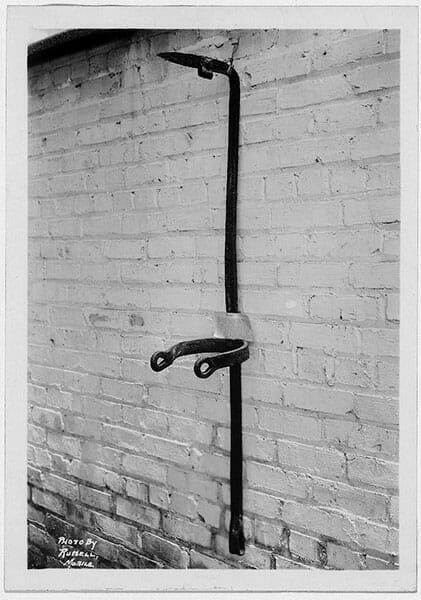

Bell Rack

The enslaved performed work according to age, gender, and physical condition. Able-bodied men and some women worked as plow-hands. Slaves usually began working in the fields between the ages of eight and twelve. Most women, however, hoed weeds, which was less strenuous than plowing. Children and elderly or disabled slaves tended livestock and maintained the yard around the plantation house. A small number of slaves acquired skills such as blacksmithing, masonry, and carpentry. Typically, slaves were in the fields before sunrise every day of the week except Sunday and worked until sunset: Saturdays often involved a half-day’s labor. Before retiring to their cabins for the evening, slaves chopped wood, repaired tools, and tended vegetable gardens, among other tasks. The spring planting and the fall harvest seasons were strenuous times when slaves labored 14 or more hours daily.

Bell Rack

The enslaved performed work according to age, gender, and physical condition. Able-bodied men and some women worked as plow-hands. Slaves usually began working in the fields between the ages of eight and twelve. Most women, however, hoed weeds, which was less strenuous than plowing. Children and elderly or disabled slaves tended livestock and maintained the yard around the plantation house. A small number of slaves acquired skills such as blacksmithing, masonry, and carpentry. Typically, slaves were in the fields before sunrise every day of the week except Sunday and worked until sunset: Saturdays often involved a half-day’s labor. Before retiring to their cabins for the evening, slaves chopped wood, repaired tools, and tended vegetable gardens, among other tasks. The spring planting and the fall harvest seasons were strenuous times when slaves labored 14 or more hours daily.

Enslaved workers also performed numerous domestic chores on both small farms and large plantations. Many enslaved women were owned by small farmers and worked as domestic servants. Wealthy planters generally had multiple domestic servants, whose duties ranged from cooking and cleaning to driving carriages, serving meals, and nursing children.

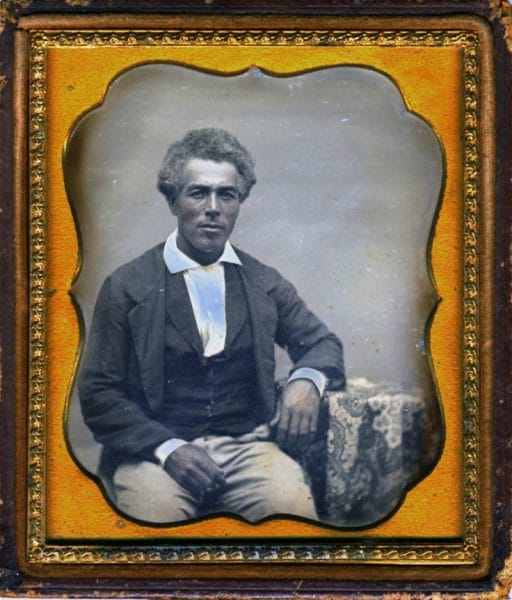

Horace King

A small number of slaves worked in Alabama’s rising industrial sector. Textile manufacturers such as the Hobbs brothers used slave labor in their Limestone County factory. In Huntsville, slaves operated the Bell Factory’s 100 looms and 3,000 spindles. Iron manufacturing pioneers Horace Ware and Moses Stroup trained slaves to work their furnaces. Slaves also worked as coal miners, harbor pilots, and railroad brakemen. In an extraordinary example, engineer John Godwin appointed slaves, including Horace King, to supervise, sometimes independently, the construction of several bridge projects in Alabama. King’s engineering talents helped him earn his freedom in 1846.

Horace King

A small number of slaves worked in Alabama’s rising industrial sector. Textile manufacturers such as the Hobbs brothers used slave labor in their Limestone County factory. In Huntsville, slaves operated the Bell Factory’s 100 looms and 3,000 spindles. Iron manufacturing pioneers Horace Ware and Moses Stroup trained slaves to work their furnaces. Slaves also worked as coal miners, harbor pilots, and railroad brakemen. In an extraordinary example, engineer John Godwin appointed slaves, including Horace King, to supervise, sometimes independently, the construction of several bridge projects in Alabama. King’s engineering talents helped him earn his freedom in 1846.

Material Conditions

Enslaved Family Hearth

During the antebellum period, the material conditions of most slaves in Alabama improved in comparison with their colonial-era ancestors. This improvement partly resulted from the closure of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade in 1808, which forced slaveholders to create conditions in which the region’s slave population would continue to expand internally without the continued importation of African slaves. Thus, owners had to provide slaves with better rations and keep them healthier because with external supplies cut off, replacements were not as readily available. Slaves received a weekly allotment of a peck (eight quarts) of cornmeal and two-and-a-half to four pounds of pork. Slave clothing was utilitarian. Plantation owners typically issued clothing twice annually. Most of the clothing was made from coarse cotton materials or sometimes wool. Slaves lived in small cabins that measured less than 300 square feet of living space and were generally inhabited by a single family. Located close to the fields, the cabins typically were built out of roughly hewn logs. Some cabins had wood plank floors, but most had only dirt floors.

Enslaved Family Hearth

During the antebellum period, the material conditions of most slaves in Alabama improved in comparison with their colonial-era ancestors. This improvement partly resulted from the closure of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade in 1808, which forced slaveholders to create conditions in which the region’s slave population would continue to expand internally without the continued importation of African slaves. Thus, owners had to provide slaves with better rations and keep them healthier because with external supplies cut off, replacements were not as readily available. Slaves received a weekly allotment of a peck (eight quarts) of cornmeal and two-and-a-half to four pounds of pork. Slave clothing was utilitarian. Plantation owners typically issued clothing twice annually. Most of the clothing was made from coarse cotton materials or sometimes wool. Slaves lived in small cabins that measured less than 300 square feet of living space and were generally inhabited by a single family. Located close to the fields, the cabins typically were built out of roughly hewn logs. Some cabins had wood plank floors, but most had only dirt floors.

Family

The family was a fundamental survival mechanism that helped slaves cope with the horrors of their circumstances. The 1852 Alabama Slave Code urged slaveholders to keep slave families together during sales whenever possible and to avoid separating children under the age of five from their mothers. Although many owners ignored the statute, its passage reflected the increasing value that some legislators placed upon maintaining families among the enslaved.

Most antebellum slaves lived in so-called nuclear families (father, mother, and children). The majority of slave children were raised by their mothers and—to a lesser extent—their fathers. Compared to their white counterparts, slave families had more mother-headed households and were less patriarchal, and their typical lack of status and property undermined expressions of male authority. Slave families also lacked the institutional and legal rights and protections of white families. Some owners also undermined parental roles regarding familial affection, discipline, and religion. O. J. McCann, a Jefferson County slaveholder, recalled that he cajoled slave children by giving them special treats such as cornbread and cups of milk that their enslaved parents could not provide.

Religion

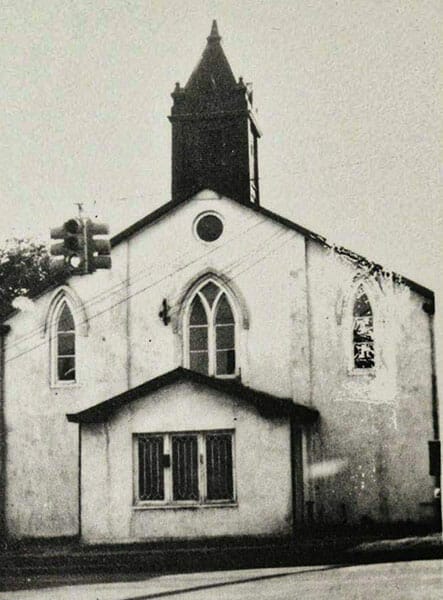

St. Bartley Primitive Baptist Church

Evangelical Christianity dominated the religious life of Alabama’s slave population. During Alabama’s territorial period, slaveholders were only marginally interested in efforts to Christianize slaves. Attitudes began to change during the mid-eighteenth century, however, when large percentages of slaves converted to Christianity as a result of the Great Awakening (a period of religious fervor that swept the American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s). Decades later, during the Second Great Awakening (c.1790-1840), a brand of evangelical Christianity spread among southern slaveholders that was inspired by revivals targeting both masters and slaves. Like their white owners, the majority of slaves in Alabama were Baptists and Methodists. In 1808, the African Huntsville Church was founded, and by 1849 its membership rolls had swelled to more than 400 slaves. Similar independent black churches existed elsewhere in Alabama. White churches routinely baptized and extended membership to slaves. Antebellum churches often had segregated seating areas for black worshipers. The spread of evangelical Christianity among slaves was influenced by sermons delivered by preachers who warned slaveholders to promote the faith among their slaves or risk damnation. Slaveholders were equally motivated to spread Christianity among their slaves in response to northern abolitionists who criticized the morality of Christian believers who owned slaves.

St. Bartley Primitive Baptist Church

Evangelical Christianity dominated the religious life of Alabama’s slave population. During Alabama’s territorial period, slaveholders were only marginally interested in efforts to Christianize slaves. Attitudes began to change during the mid-eighteenth century, however, when large percentages of slaves converted to Christianity as a result of the Great Awakening (a period of religious fervor that swept the American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s). Decades later, during the Second Great Awakening (c.1790-1840), a brand of evangelical Christianity spread among southern slaveholders that was inspired by revivals targeting both masters and slaves. Like their white owners, the majority of slaves in Alabama were Baptists and Methodists. In 1808, the African Huntsville Church was founded, and by 1849 its membership rolls had swelled to more than 400 slaves. Similar independent black churches existed elsewhere in Alabama. White churches routinely baptized and extended membership to slaves. Antebellum churches often had segregated seating areas for black worshipers. The spread of evangelical Christianity among slaves was influenced by sermons delivered by preachers who warned slaveholders to promote the faith among their slaves or risk damnation. Slaveholders were equally motivated to spread Christianity among their slaves in response to northern abolitionists who criticized the morality of Christian believers who owned slaves.

Resistance

No slave rebellions took place in Alabama; most acts of resistance took a more passive or clandestine form. Common acts of daily resistance included faking illness, breaking tools, and running away. State newspapers such as the Mobile Register regularly published advertisements placed by white owners seeking the capture and return of runaway slaves, yet few slaves actually gained their freedom by running away. Most runaway slaves sought temporary relief from their work and often did not travel far from their home plantation or farm.

Only on rare occasions did slaves resist their bondage violently. Slaves occasionally physically attacked their owners or overseers. Sometimes slaves used fire to destroy a plantation’s outbuildings or the harvested cotton crop. Such incidents were exceptional, however. Nonetheless, the 1852 Alabama Slave Code made the voluntary manslaughter of a white person by a slave a capital offense.

Punishment

Slaveowners used a variety of punishments to discipline and dominate slaves. Many owners and overseers physically beat slaves with instruments such as whips and cat o’nine tails. Slaves were most often beaten for working too slowly, stealing, running away, and disobeying owners or overseers. Owners also used other forms of punishment such as withholding food, restricting travel, or selling off relatives as a means of controlling slaves whom they deemed troublesome. Female slaves also endured sexual abuse committed upon them by white men, including acts of rape and molestation.

Slavery and Alabama Politics

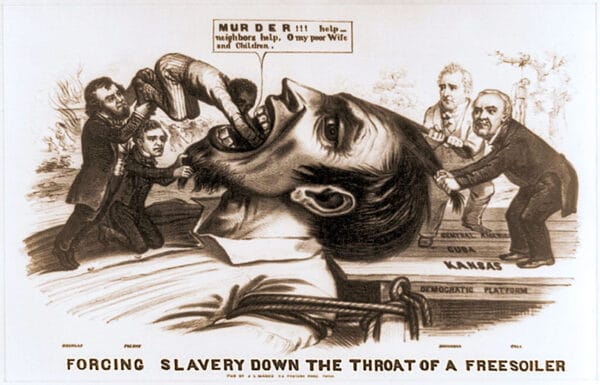

Anti-Slavery Cartoon, 1856

During the antebellum period, Alabama politicians such as William Lowndes Yancey and J. L. M. Curry actively defended the right to expand slavery into areas acquired by the United States through the Louisiana Purchase (1803) and Mexican War (1846-48). In 1848, state Democrats issued the Alabama Platform in response to the Wilmot Proviso, a piece of legislation that proposed excluding slavery from any newly acquired territory resulting from the Mexican War. The Alabama Platform aimed to ban state Democrats from supporting any presidential candidate who favored the Wilmot Proviso or popular sovereignty—the right of territorial legislatures to determine the status of slavery before statehood. The national Democratic Party failed to adopt the Alabama Platform on two occasions—1848 and 1860—a reflection of the state’s limited national political influence. During the 1860 Democratic National Convention held in Charleston, South Carolina, delegates from Alabama and six other slave states, under Yancey’s leadership, walked out of the meeting in protest of the party’s nomination of Sen. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. Pro-slavery proponents saw Douglas’s Freeport Doctrine, which argued that slavery could not exist in a territory without police regulations to protect it, as a threat to slavery. Alabama’s support for the preservation and expansion of slavery ultimately led the state to secede from the United States following the election of Republican Party presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Lincoln’s platform, that slavery should be prohibited from expanding into areas of the country where it did not currently exist, alarmed southern slaveholders. At the time of Alabama’s secession, more than 435,000 slaves were held in bondage in Alabama.

Anti-Slavery Cartoon, 1856

During the antebellum period, Alabama politicians such as William Lowndes Yancey and J. L. M. Curry actively defended the right to expand slavery into areas acquired by the United States through the Louisiana Purchase (1803) and Mexican War (1846-48). In 1848, state Democrats issued the Alabama Platform in response to the Wilmot Proviso, a piece of legislation that proposed excluding slavery from any newly acquired territory resulting from the Mexican War. The Alabama Platform aimed to ban state Democrats from supporting any presidential candidate who favored the Wilmot Proviso or popular sovereignty—the right of territorial legislatures to determine the status of slavery before statehood. The national Democratic Party failed to adopt the Alabama Platform on two occasions—1848 and 1860—a reflection of the state’s limited national political influence. During the 1860 Democratic National Convention held in Charleston, South Carolina, delegates from Alabama and six other slave states, under Yancey’s leadership, walked out of the meeting in protest of the party’s nomination of Sen. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. Pro-slavery proponents saw Douglas’s Freeport Doctrine, which argued that slavery could not exist in a territory without police regulations to protect it, as a threat to slavery. Alabama’s support for the preservation and expansion of slavery ultimately led the state to secede from the United States following the election of Republican Party presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Lincoln’s platform, that slavery should be prohibited from expanding into areas of the country where it did not currently exist, alarmed southern slaveholders. At the time of Alabama’s secession, more than 435,000 slaves were held in bondage in Alabama.

Conclusion

The outcome of the American Civil War ended slavery in Alabama. The Thirteenth Amendment permanently abolished slavery in the United States in 1865. Alabama freedpeople welcomed emancipation but endured continuing hardships because of the prevailing and pervasive racial prejudices of the state’s white inhabitants. Alabama’s antebellum-era slave codes were replaced by a social and legal system of separating citizens on the basis of race that remained intact through the mid-twentieth century. The racist ideology that had once excused the actions of the state’s slaveholders survived the Civil War and emancipation and carried over in the form of an array of Jim Crow laws that trampled upon the civil liberties of African Americans until they were overturned during the civil rights movement.

Further Reading

- Baptist, Edward E. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. New York: Basic Books, 2014.

- Kolchin, Peter. American Slavery: 1619-1877. 2nd edition. New York: Hill and Wang, 2003.

- Sellers, James Benson. Slavery in Alabama, Library Alabama Classics. 2nd edition. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.

- Thornton, J. Mills. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.

- Williams, Horace Randall, ed. Weren’t No Good Times: Personal Accounts of Slavery in Alabama. Winston-Salem, N.C.: John F. Blair, 2004.