Public Education in the Early Twentieth Century

As political power in Alabama returned to the hands of the white elite after Reconstruction, education in the state reflected this transformation. Whites solidified and codified segregation, provided disproportionate funding to white and black schools, and finally created a constitution that removed power from local school systems and centralized it in the hands of the legislature in Montgomery. As the Progressive Era faded in the 1920s and 1930s, however, attempts were made to reform education, by addressing illiteracy and chronic underfunding.

Prior to 1891, state education funds had been allocated by the number of students by race, which meant a fairly equitable racial division of funding. That year, however, the state allowed counties and cities to divide education funding as they saw fit, leading to the inequity that became a hallmark of segregated school systems throughout the South. Local jurisdictions gave white schools the bulk of school funds and greatly reduced already inadequate funding to black schools. Lack of money became the biggest barrier to educational progress, as efforts to allow local school districts the power to levy taxes for school funding were defeated at every turn and efforts to assess higher property values for taxation met a similar fate.

In 1901, the legislature approved a new constitution that further stymied local attempts to increase education funding and implement reforms. It required that counties and local municipalities desiring to raise property taxes for education (and other uses) or implement reforms submit amendments to the constitution subject to statewide votes. The anti-tax attitude held by many residents usually meant failure for local education-funding initiatives. Despite the opposition to reform embedded in the 1901 document, education advocates succeeded in accomplishing some school improvements in the early twentieth century, including adopting uniform textbooks, redrawing system boundaries along natural municipal and county lines, and standardizing superintendent duties.

In the early 1900s, education in Alabama still suffered from short school terms, low funding, and racism. In one county, for instance, the average length of the school year was 72 days for white students and only 34 days for African Americans students. The value of the typical school property for whites was $40,000, in contrast to black school property valued at only $1,000. The average annual salary for white male teachers was $863 and for white female teachers $422, whereas African American male teachers earned $480, and black women teachers earned just $140. The stark contrast in support for rural teachers and systems compared to those in the cities was also striking.

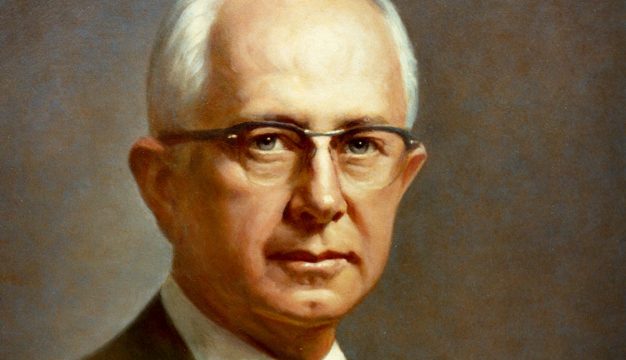

Braxton Bragg Comer, who served as governor from 1907 to 1911, became known as "the education governor." He pushed through legislation that required a high school in every county, and by 1918, 57 of 67 counties had a high school. He increased funding for schools and set compulsory school attendance until age 16. The battle over compulsory attendance reflected the racial attitudes in the state. Many whites opposed it because it could improve black education, but to Comer's credit he argued that black education was not, as opponents had asserted, wasted. Ten years later, however, school attendance had increased only one percent.

Also under Comer, the state hoped to increase tax revenue by creating a State Tax Commission and State Board of Equalization with the authority to equalize property assessments. As a result, the assessed value of property went up, but equalization of property assessment and taxation remained problematic. By 1912, property was taxed at only 25 percent of its estimated value, although the state revenue code set the ceiling on assessment at 60 percent. However, the primary source of a state's revenue and its ability to support public education derived from property taxes, therefore such low assessments restricted the amount of money the state could budget for basic functions.

In 1918, the Russell Sage Foundation issued a report on Alabama, entitled "Social Problems of Alabama," that offered a long list of the state's deficiencies in the wake of its incredible industrial growth. According to the report, the state had succeeded in fostering industry but had failed in serving its citizens. At the time, the illiteracy rate for children 10 and older reached 12.1 percent; the rate was 6.4 percent among whites, and 31.3 percent among African Americans. Partly in response to the report, Alabama elected two more reformist governors, Thomas E. Kilby (1919-1923) and Bibb Graves (1927-1931, 1935-1939). Under these men, the state restructured the Board of Education, created and funded an illiteracy program, and increased the property tax valuation toward the 60 percent limit. In 1927, the state passed an education reform package and the largest educational appropriation until that time, constituting $600,000 in emergency funds and $25 million over four years, compared with $10 million appropriated for the preceding four years. The reform law mandated a minimum seven-month school term state wide for both blacks and whites, established the Division of Negro Education with two state-level African American employees, raised teacher pay from an average of $689 per year in 1926 to $761 in 1929, and created an Opportunity School in every county where 15 or more students promised to attend. These schools aimed to reach individuals 21 years old and above to battle the state's high illiteracy rates.

In addition, lawmakers established the Alabama Special Education Trust Fund (ASETF) in 1927 to provide more consistent funding. Money came from a variety of sources, including various levels of taxation on intra-state railroad business, telephone and telegraph company receipts, tonnage mined from coal mines and iron ore, and the wholesale price of tobacco products.

Familiar problems remained at the end of the Progressive Era, however, as only one in 11 rural children attended high school, compared with one out of six in Alabama towns. The average school term for rural schools remained low at 123 days, some 49 days shorter than school terms in towns, as funding and local districts often determined the length of the school year, despite the state's mandates. Economic class considerations dominated as 84 percent of landowners' children went to school, compared with only 58 percent of sharecroppers' children. Also, racism remained pervasive in the state, and in the mid-1920s, white schools received some $13.1 million in funds, and black schools received only $1.4 million. Unfortunately, even the meager gains that the state enjoyed in education during the Progressive Era were erased with the onset of the Great Depression, following the stock market crash of 1929.

During the Great Depression, many school districts in Alabama struggled even to keep school doors open, much less repair or replace dilapidated buildings. Parents often were required to pay school fees to keep schools from closing, while the schools themselves, in many instances, failed to offer anything more than the most rudimentary education. The declining economy led to downturns in property tax collection, which was the primary source of state and education funding revenue. In 1910, the state collected 55.6 percent of its total revenue from property taxes, but by 1930, that number had fallen to 26.6 percent.

The state also struggled to pay teacher salaries during this time. Only 16 of 116 Alabama school systems paid teachers in full in 1932. In Winston County, teachers went an entire year without pay. In 1933, the Montgomery Board of Education threatened to close its schools for lack of funds unless teachers took a major cut in pay. Resistance to that plan by parents and teachers, however, led to a compromise in which teachers received part of their pay in cash and the remainder in "vouchers" issued by the school board that were accepted by local businesses, and the schools remained open.

Data from 1932 and 1933 reveal just how bad the situation had become. That school year, more than 50,000 white children, mostly in rural areas, had school terms of three months or less. Another 129,000 had terms of 5 months or less, and almost another 50,000 did not enroll at all because they had no school to go to or because very short terms were not worth the effort. In all, some 227,000 school children in Alabama attended school for only five months or less.

Through the New Deal era of the 1930s, education recovered slowly. If there was some positive aspect to the Great Depression, it was that the financial chaos forced lawmakers to reassess and reform the state's finances. The depression provided Alabama and Gov. Bibb Graves the unique opportunity to enact legislation that benefited Alabama education, including the 1935 Textbook Act, which provided free textbooks for the first through third grades; the Minimum Program Act of 1935, which attempted to appropriate enough school funds to ensure a statewide seven-month school term; and the School Budget Act of 1935, which forbade local school boards (67 county boards and 45 city boards) from spending more on education in any given year than the revenue receipts plus cash on hand. In short, it prevented local boards from deficit spending.

It took a great deal of time for education in Alabama to recover from the Depression. The economic boom associated with spending during World War II, however, provided the state with huge gains in tax collections. In 1932, the state had a shortfall of $17 million, but by 1942, it was in the best shape financially since it had become a state, closing the budget year with a $25 million surplus. In 1943, the state enacted an eight-month school year, and five years later, it enacted a nine-month term.

The economic boom soon gave way to economic decline in the 1950s, as state tax revenues declined and education suffered crippling budget proration that threatened to erase the recent gains. Another issue also was looming on the horizon as several school desegregation cases worked their way through the federal courts. In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education decision ushered in dramatic changes to public education in the state, and issues of funding and efficiency issues were overshadowed by the development of the civil rights movement, which began the slow, painful, and often violent process of integrating the state's segregated school systems.

Additional Resources

Griffith, Lucille. Alabama: A Documentary History to 1900. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1968.