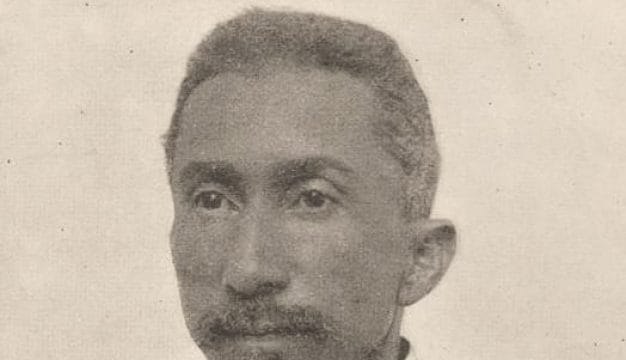

Lilius Bratton Rainey

Lilius Bratton Rainey (1876-1959) served in the U.S. Congress representing Alabama's Seventh Congressional District as a Democrat from 1919 until 1923. Rainey filled this seat following the death of John Lawson Burnett. Rainey also succeeded Burnett in his seat on the Committee of Immigration and Naturalization where he was a strong proponent of limiting immigration. Before and after his time in Congress, Rainey primarily worked as a lawyer in northern Alabama.

Lilius Bratton Rainey

Lilius Bratton Rainey was born on July 21, 1876, in Dadeville, Tallapoosa County, to Samuel Rainey and Elizabeth Walker; he had at least one sibling, a sister. The family had moved to Fort Payne, DeKalb County, by 1900, where his father operated a boarding house and hotel. The daughter would later operate the popular Hotel Rainey there. As a child, Rainey attended local schools and then entered the Alabama Polytechnical Institute (API), now Auburn University, in Auburn, Lee County, for his college education. At API, Rainey participated in many clubs and social activities, including membership in Pi Kappa Alpha, being voted class vice president for the 1897-98 academic year, and as a senior, being named editor-in-chief of the school's yearbook, the Glomerata. After graduating from API, Rainey entered law school at the University of Alabama, graduating in 1902. That summer, he married Ethel Skinner at her parents' home in Selma, Dallas County. After the ceremony, they left for their new home in Gadsden, Etowah County, where Rainey began establishing himself as a new attorney.

Lilius Bratton Rainey

Lilius Bratton Rainey was born on July 21, 1876, in Dadeville, Tallapoosa County, to Samuel Rainey and Elizabeth Walker; he had at least one sibling, a sister. The family had moved to Fort Payne, DeKalb County, by 1900, where his father operated a boarding house and hotel. The daughter would later operate the popular Hotel Rainey there. As a child, Rainey attended local schools and then entered the Alabama Polytechnical Institute (API), now Auburn University, in Auburn, Lee County, for his college education. At API, Rainey participated in many clubs and social activities, including membership in Pi Kappa Alpha, being voted class vice president for the 1897-98 academic year, and as a senior, being named editor-in-chief of the school's yearbook, the Glomerata. After graduating from API, Rainey entered law school at the University of Alabama, graduating in 1902. That summer, he married Ethel Skinner at her parents' home in Selma, Dallas County. After the ceremony, they left for their new home in Gadsden, Etowah County, where Rainey began establishing himself as a new attorney.

As Rainey settled into civic life in Gadsden, he was elected captain of the Etowah Rifles, a company in the Alabama National Guard, in 1903. The unit soon after renamed itself the Queen's City Guard. Rainey held this position until 1907 when he resigned. For many years, Rainey was a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, holding formal positions such as adjutant and historian during his tenure with the organization. With the Sons of Confederate Veterans and at the invitation of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Rainey often made speeches and remarks at public events that memorialized the Confederacy and supported Lost Cause ideology. In July 1911, Rainey married Julia LaCoste Smith of Gadsden; the couple would have four children. One son served with the U.S. Army in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam and achieved the rank of major. Rainey and Smith would later divorce.

Rainey's first formal electoral campaign came when he ran for the position of solicitor of the Gadsden city court in 1910. He entered this race with the perception of being a young, successful lawyer who possessed a strong reputation within his profession and the local community. In the Democratic primary, Rainey won a tight race, defeating the incumbent by 61 votes and in the general election, Rainey handily defeated his opponent to win the position.

In 1914, Rainey made his first foray into national politics as he ran for Alabama's Seventh District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. He lost to the incumbent John L. Burnett in the Democratic primary by several thousand votes. Two years later, Rainey again challenged Burnett. To prepare for the race, Rainey resigned from his position as solicitor of the Gadsden city court. He again lost in the primary, but he narrowed the voting margin and even took the majority in his county. During these campaigns, Rainey championed the expansion and improvement of Alabama's education system. Rainey argued that improving educational standards in the state should transcend political parties because Alabama had an obligation to be an upholder and promoter of education and American values. Rainey's arguments on improving education were aimed at improving the educational standards for white Alabamians.

In 1919, after the death of John Lawson Burnett, Rainey again ran for the Seventh Congressional District seat in the 66th Congress in a special election. The district, which was composed of Cherokee, De Kalb, Marshall, Etowah, and St. Clair Counties, or portions thereof, had been the last congressional district to be retaken by the Democrats during the Populist and Republican wave of the 1890s and generated tight general elections. This election, following the end of World War I, included discussion of issues of national interest, as Democrats and Republicans fiercely campaigned on issues concerning the Versailles Peace Treaty and the League of Nations, both of which were championed and heavily influenced by the Democratic president, Woodrow Wilson. As a Democrat, Rainey supported both issues and defeated Republican Charles Kennamer by fewer than 1,000 votes and took office on September 30.

During Rainey's first term in Congress, he served on the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, as well as the Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures. Rainey's appointment to the Immigration Committee broke with tradition as he gained the position over more senior members of Congress because Burnett served on the committee. Rainey, like much of the Alabama delegation, voted on April 9, 1920, against a "peace resolution" successfully passed by the Republican-led House of Representatives to formally end the war with Germany, but also resume trade with the former enemy and to affirm the House's right to engage in peacemaking. Democrats claimed the resolution unconstitutional because it undermined the treaty-making authority of the Senate and President and was an attempt in Rainey's and Democratic views to embarrass the Wilson administration during an election year. Rainey, on June 30, 1921, in his second term, voted against the Knox-Porter Resolution that formally ended the war with Germany and Austria-Hungary, a vote that split House Democrats and the Alabama delegation. He abstained from voting on the conference report on the resolution.

In 1920, Rainey again faced a fierce general election from Kennemar. As with the previous election, the final tally came within 1,000 votes. This time, Kennamer formally challenged the election results and argued that Rainey had tried to block the registration of newly enfranchised women voters who were going to vote Republican as well as enabling the unlawful registration of Democratic voters. This challenge went before the House Committee on Elections, whose members unanimously sided with Rainey. During this process, Rainey vowed he would not run for re-election if his 1920 victory was validated. For his second term in Congress, Rainey continued to serve on the two committees from his first term as well as the Committee on Mines and Mining. In 1921, Rainey oversaw a bill that enabled the special minting of commemorative coins to celebrate Alabama's centennial, which had occurred in 1919.

The greatest influence Rainey had on congressional legislation likely came after he left office on March 3, 1923. In the twilight days of his second term, Rainey proposed legislation in December 1922 that sought to restrict immigration from southern and eastern Europe based on the 1890 Census instead of the 1910 Census and lower the quota threshold for each country from three percent to two percent. This was done because there were fewer immigrants from southern and eastern Europe in 1890 than 1910 and the quota was based on the percentage of immigrants from specific countries. Although his bill passed in the Senate, it stalled in the House of Representatives. Later, Republican congressman Albert Johnson of Washington State introduced a bill containing the same language as the one advanced by Rainey that formed the foundation for the Immigration Act of 1924. Along with his earlier bill, Rainey also proposed that acceptable immigrants possess intelligence and good moral character, understand democracy and freedom and liberty in the United States, and register with Federal Bureau of Investigation. In an April 1949 letter to the editor of the Birmingham News advocating stronger immigration rules, he wrote that this provision was aimed at keeping out spies and other "undesirables" from the United States.

Rainey did not run for reelection in 1922, and his open seat was won by Miles Clayton Allgood. During his time in Congress, Rainey became a member of the Board of Trustees for the Alabama Department of Archives and History, which he remained active with for several decades. Likewise, Rainey resumed his profession as a lawyer after leaving Congress and continued to practice for many years and remained an active of member of the Gadsden community. Rainey died in Gadsden on September 27, 1959, and was buried in Glenwood Cemetery in Fort Payne, DeKalb County.