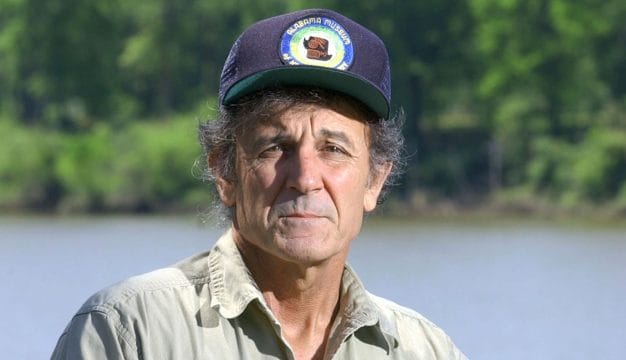

James Edwin Coyle

James Edwin Coyle

James Edwin Coyle (1873-1921) was a Catholic priest who served as pastor St. Paul's Catholic Church in Birmingham, Jefferson County, from 1904 until his death in 1921. Coyle was fatally shot while sitting on the rectory porch by Methodist minister and Ku Klux Klan (KKK) member Edwin Stephenson on August 11, 1921. Hours earlier, Coyle had officiated the marriage between Stephenson's daughter and Puerto Rican American Pedro Gussman. Stephenson, who was defended by future U.S. Supreme Court justice Hugo Black, was notoriously acquitted by an all-white jury, highlighting the racial bigotry and anti-Catholic sentiment in Alabama. The case and verdict in turn, brought Hugo Black statewide attention.

James Edwin Coyle

James Edwin Coyle (1873-1921) was a Catholic priest who served as pastor St. Paul's Catholic Church in Birmingham, Jefferson County, from 1904 until his death in 1921. Coyle was fatally shot while sitting on the rectory porch by Methodist minister and Ku Klux Klan (KKK) member Edwin Stephenson on August 11, 1921. Hours earlier, Coyle had officiated the marriage between Stephenson's daughter and Puerto Rican American Pedro Gussman. Stephenson, who was defended by future U.S. Supreme Court justice Hugo Black, was notoriously acquitted by an all-white jury, highlighting the racial bigotry and anti-Catholic sentiment in Alabama. The case and verdict in turn, brought Hugo Black statewide attention.

Coyle was born on March 23, 1873, in Roscommon County, Ireland, to Owen and Margaret Letitia Durney Coyle; he had at least two siblings: a sister, and a brother who also became a priest. He was ordained as a Roman Catholic priest in Rome on May 30, 1896, and likely soon after set sail for Mobile, Mobile County. There, he served first as an instructor, and later as first Rector (president) of McGill Institute for Boys in the Diocese of Mobile from 1896 to 1904. That year, Bishop Edward P. Allen appointed Coyle as pastor of St. Paul's Catholic Church in Birmingham. (The Mobile Diocese consisted of the entirety of the state until 1969, when Birmingham would become the seat of its own diocese and St. Peter's was elevated to the status of a cathedral as the seat of the diocese.) Coyle became a naturalized American citizen in 1904 and registered for the draft in 1918 during World War I.

The relatively young pastor was welcomed with open arms into the parish and is remembered for his call for regular mass attendance and general charisma. During this time period, however, the rise of the KKK and True Americans (a sister-group of sorts to the Klan that was highly active in the South, most notably in Birmingham) in the 1910s and 1920s would be the most challenging aspect of Coyle's tenure as pastor.

Both organizations promoted white supremacy through legal and often violent extralegal means, and they also strongly opposed the rights of Catholics and Jews. These groups spread anti-Catholic propaganda, including that the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic fraternal organization, was hoarding weapons and ammunition to overthrow the government. Coyle ardently denounced these ideas and even had numerous "opposite the editorial page" or op-ed pieces printed in Birmingham area newspapers looking to counter this misinformation. Coyle's unwavering defense of the Catholic faith would result in numerous threats against his life and his church, yet he continued to fight the spread of anti-Catholic misinformation.

On August 11, 1921, Coyle officiated at the marriage of Ruth Stephenson, daughter of Methodist minister and Klansman Edwin Stephenson, to Pedro Gussman, a Catholic of Puerto Rican descent. Ruth had recently been baptized Catholic after years of secret fascination with the Church. According to friends, Coyle reportedly said that he would be killed for performing the marriage after receiving the phone call with the couple's request. Upon learning of the marriage, Stephenson walked down to the porch of the rectory, where Coyle sat every evening, and fatally shot him in the head. Stephenson immediately turned himself in and newspaper accounts at the time report that he told a deputy he killed Coyle because of the marriage. Coyle was pronounced dead upon arrival at the hospital and was buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Birmingham.

The subsequent trial became perhaps more infamous than the murder itself. Some older sources say the Klan was heavily involved, with members sitting on the jury and defense team for instance, but more recent and reputable scholarly research questions these sources and their motives. Future U.S Supreme Court justice Hugo Black, who would join the Klan two years after this trial before renouncing his membership later in life, agreed to defend Stephenson. He pleaded not guilty to the murder charge, claiming that he shot Coyle out of self-defense. In the multi-day trial, insinuations of a scuffle between the two ministers and an excuse of Stephenson being temporarily insane were brought up, and the final day of the trial included the most polarizing moment of all. Black called Pedro Gussman to stand before the jury and questioned him about his general looks and skin color, clearly insinuating that Gussman was Black and that his race played a factor in whether the killing of Coyle was justified in the eyes of Alabama's white supremacist society. Several prominent historians note that the case was just one of many that Black won over Black, Catholic, and Jewish defendants by relying on all-white, middle-class, and Protestant juries and it brought him statewide attention. Stephenson was acquitted later that day, October 20, 1921, and lived as a free man in the Birmingham area for another 35 years before dying in 1956.

The Cathedral of St. Paul holds a commemorative mass every year on August 11 to honor Coyle's martyrdom, and the Father James E. Coyle Memorial Project organization has been created to share his life story, as well as archive digitalize his numerous writings.

Further Reading

- Davies, Sharon L. Rising Road: A True Tale of Love, Race, and Religion in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Freyer, Tony A., ed. Justice Hugo Black and Modern America. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

- Suitts, Steve. Hugo Black of Alabama: How His Roots and Early Career Shaped the Great Champion of the Constitution. Montgomery: New South Books, 2005.