George Washington Carver Museum

George Washington Carver Museum

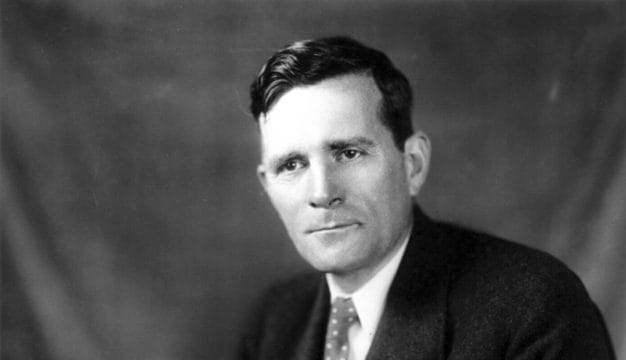

The George Washington Carver Museum in Tuskegee, Macon County, commemorates the life and achievements of George Washington Carver, the world-renowned African American scientist and Tuskegee Institute professor. He is best known as the inventor of more than 100 industrial product substitutes from the peanut. First established in 1941, the museum houses collections related to the early life, education, art, teaching career, research, and legacy of Carver, and it also serves as a repository and exhibition hall for other Tuskegee University artifacts and art collections. The museum is one of the two major facilities owned and operated by the National Park Service (NPS) within the Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site (TINHS), located on the campus of Tuskegee University. The building also serves as the TINHS visitor and information center.

George Washington Carver Museum

The George Washington Carver Museum in Tuskegee, Macon County, commemorates the life and achievements of George Washington Carver, the world-renowned African American scientist and Tuskegee Institute professor. He is best known as the inventor of more than 100 industrial product substitutes from the peanut. First established in 1941, the museum houses collections related to the early life, education, art, teaching career, research, and legacy of Carver, and it also serves as a repository and exhibition hall for other Tuskegee University artifacts and art collections. The museum is one of the two major facilities owned and operated by the National Park Service (NPS) within the Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site (TINHS), located on the campus of Tuskegee University. The building also serves as the TINHS visitor and information center.

The building that houses the museum was built in 1915 and served as the Tuskegee Institute's campus laundry until 1938. In that year, it was gutted by the school in anticipation of establishing a museum dedicated to Carver. Carver himself provided much of the funding for the new museum. Between the 1938 decision to found the museum and its dedication and grand opening in November 1941, Carver helped school officials gathered artifacts from his laboratory in Milbank Hall, his home, and his private art collection to populate the museum exhibits. Modest regarding his widely celebrated agricultural research, Carver wanted the museum to reflect above all his longstanding passion for painting, his original major at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa, before shifting his academic focus to plant biology at Iowa State College in Ames. Accordingly, much of the exhibition space in the museum was devoted to displaying Carver's paintings of botanical specimens and landscapes, with a smaller section dedicated to his better-known accomplishments in plant biology and chemistry.

In December 1947, a fire broke out in the building, destroying some of the scientific exhibits and the majority of Carver's paintings. The curator and museum staff augmented the salvaged collections with other laboratory equipment stored on campus, documents and correspondence related to

Carver, George Washington

Carver's education and career, pictures, paintings, and sculptures depicting Carver, and newspaper and magazine articles lauding Carver's contributions. Thereafter, the museum's exhibition hall primarily stressed his scientific, educational, and artistic accomplishments.

Carver, George Washington

Carver's education and career, pictures, paintings, and sculptures depicting Carver, and newspaper and magazine articles lauding Carver's contributions. Thereafter, the museum's exhibition hall primarily stressed his scientific, educational, and artistic accomplishments.

Tuskegee Institute was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. In 1974, the U.S. Congress authorized the Department of the Interior (the bureaucratic entity responsible for administering the NPS) to purchase three buildings in Tuskegee from the institute for the purposes of funding their administration and maintenance: the Carver Museum, Booker T. Washington's home (The Oaks), and Grey Columns, an antebellum home adjacent to campus. In 1977, Tuskegee Institute was declared a National Historic Site that now encompasses the 50-acre campus district. Tuskegee University retains ownership of the other buildings and roads, but the NPS is authorized to create historic markers and heritage trails. Congress allotted $2.7 million for the maintenance and development of the TINHS, a general fund that the NPS administration and park rangers on site use for maintaining the buildings, developing tourism, creating exhibits, and paying the utilities. This fund receives annual disbursements from the Department of the Interior to subsidize day-to-day operations.

The Carver Museum contains several paintings, statues, and wood carvings of Carver's likeness, including a massive portrait painting of the botanist next to an orchid and a life-size bronze bust of him looking down at peanut shells in his hands that visitors encounter upon entering the museum. An audio exhibit of a recording of Carver reading his favorite poem, Edgar A. Guest's "Equipment" (an ode to every person's capacity for self-betterment which aligned with Washington's vision of African American improvement at Tuskegee), conveys to guests Carver's ability to inspire students. A display that includes a list of the more than 300 substitute products that Carver crafted from peanuts, sweet potatoes, and other plants and canisters of some of those products testifies to Carver's ingenuity as a chemist.

Another exhibit contains artifacts that Carver recovered from his childhood home in Diamond Grove, Missouri. These items include a tin lantern, a broken plate, rusted utensils, and a miniature chalkboard. They highlight both the poverty Carver experienced as a slave in his early life and the instruction in grammar and arithmetic that he received from his former owners, Moses and Susan Carver, after his 1865 emancipation. Other artifacts include the typewriter that Carver purchased before applying to Highland College in Highland, Kansas (he was refused entry because the school did not admit blacks), original drawings of botanical specimens, and his Iowa State College senior thesis on plant modification. These items introduce visitors to Carver's broad formative education, his personal experiences with discrimination, and his persistent pursuit of scholarly goals.

School on Wheels

Some of the museum space is dedicated to Carver's impact as a teacher during his 47 years at Tuskegee Institute. On exhibit is a copy of the job offer that Washington made to Carver in 1896: Washington could not offer the botanist much money but beseeched him to use his mental gifts to improve the lives of the black community. Teaching aids include samples from Carver's extensive rock collection and an ox skeleton. Other exhibits, particularly the horse-drawn Jesup Wagon and the motorized Tuskegee Institute Movable School, speak to Carver's broader educational legacy with the Agricultural Extension Service and his work with federal extension agent Thomas Monroe Campbell. Carver used the vehicles to reach the remote farms of rural blacks living in Alabama and provide instruction in more modern housekeeping and farming techniques. Photos and magazine articles highlight Carver's national fame and accolades, and an exhibit stressing developments in soil conservation, plant product innovations, and Tuskegee scientists' collaboration with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration beginning in the 1980s speaks to his long-term influence on scientific research. A 30-minute film on Carver's life is available for viewing upon request in a large auditorium downstairs.

School on Wheels

Some of the museum space is dedicated to Carver's impact as a teacher during his 47 years at Tuskegee Institute. On exhibit is a copy of the job offer that Washington made to Carver in 1896: Washington could not offer the botanist much money but beseeched him to use his mental gifts to improve the lives of the black community. Teaching aids include samples from Carver's extensive rock collection and an ox skeleton. Other exhibits, particularly the horse-drawn Jesup Wagon and the motorized Tuskegee Institute Movable School, speak to Carver's broader educational legacy with the Agricultural Extension Service and his work with federal extension agent Thomas Monroe Campbell. Carver used the vehicles to reach the remote farms of rural blacks living in Alabama and provide instruction in more modern housekeeping and farming techniques. Photos and magazine articles highlight Carver's national fame and accolades, and an exhibit stressing developments in soil conservation, plant product innovations, and Tuskegee scientists' collaboration with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration beginning in the 1980s speaks to his long-term influence on scientific research. A 30-minute film on Carver's life is available for viewing upon request in a large auditorium downstairs.

An estimated 40,000-50,000 guests visit the museum annually, and admission is free.

Additional Resources

Conant, Roger, and Joseph Collins. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians, Eastern and Central North America. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

Mount, Robert H. Reptiles and Amphibians of Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1975.