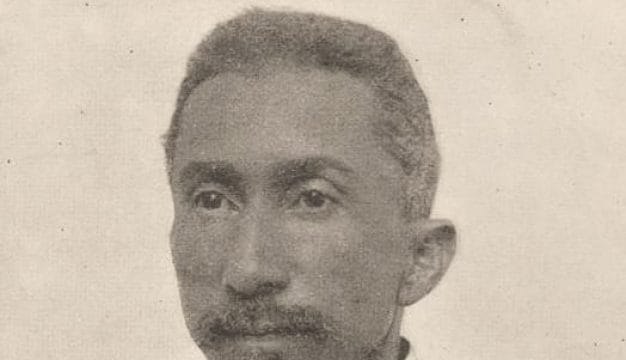

Frederick George Bromberg

Frederick George Bromberg

Frederick George Bromberg (1837-1930) served as a Liberal Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1873-75, during Reconstruction. In addition, he held a number of other political offices, including state senator, Mobile County treasurer, Mobile County postmaster, and as chairman of the Alabama delegation to the Liberal Republican National Convention. An attorney, Bromberg served as president of the Alabama State Bar and the Mobile Bar and practiced law in Mobile, Mobile County, for many years.

Frederick George Bromberg

Frederick George Bromberg (1837-1930) served as a Liberal Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1873-75, during Reconstruction. In addition, he held a number of other political offices, including state senator, Mobile County treasurer, Mobile County postmaster, and as chairman of the Alabama delegation to the Liberal Republican National Convention. An attorney, Bromberg served as president of the Alabama State Bar and the Mobile Bar and practiced law in Mobile, Mobile County, for many years.

Frederick George Bromberg was born June 19, 1837, to Frederick and Lizette Beetz Bromberg in New York City. Both of his parents were immigrants from Hamburg, Germany. He was one of four siblings. In February 1838, his family relocated to Mobile, where his father would rise to prominence by serving on the city council, the county commission, and in a county administrative position following the Civil War. His father was also a merchant and toy dealer who became quite prosperous. Bromberg attended local private schools and then Harvard University, graduating in 1858. In 1861, he joined Harvard's Chemistry Department, working in the lab of the university's future president, Charles W. Eliot; he later tutored students in mathematics. After the Civil War ended in 1865, Bromberg resigned his position at Harvard and returned to Mobile, where he entered politics.

In July 1867, Bromberg was appointed treasurer of Mobile County by Maj. Gen. John Pope, who oversaw the Third Military District during Reconstruction. The following year he was elected as a Republican to a four-year term in the Alabama State Senate and in July 1869 Pres. Ulysses S. Grant appointed him Mobile's postmaster, a position he held until 1871. In 1872, Bromberg served as chairman of Alabama's delegation to the Liberal Republican National Convention, held in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he supported the nomination of newspaper editor Horace Greeley for the presidency. The Liberal Republicans were backed by Democrats who also nominated Greeley for president in a separate convention. Both factions favored leniency and reconciliation toward the former Confederate states and therefore opposed the election of incumbent Ulysses S. Grant. Grant won the election handily and Greeley died before the Electoral College votes were counted.

In 1872, Bromberg, with the support of Democrats, defeated freedman Republican Benjamin S. Turner and freedman Independent Party candidate Philip Joseph to win election to the Forty-third Congress as a Liberal Republican. He represented the First District, which then consisted of Baldwin, Clarke, Conecuh, Covington, Dallas, Escambia, Mobile, Monroe, Washington, and Wilcox Counties, and served on the Commerce Committee. Bromberg worked on a number of issues important to Mobile and the South at large. He had supported legislation creating the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company and a branch in Mobile. It was a private corporation established under the administration of Abraham Lincoln that provided financial assistance to newly freed African Americans as they endeavored to become financially stable. While in Congress, he favored an investigation into its failure after the Panic of 1873 and authored the resolution that led to its closure. He introduced legislation to create a federal committee for internal improvements and specifically focused on legislation creating improvements at the mouth of the Mississippi River, but they failed to become law. Notably, Bromberg sponsored the very first national quarantine bill providing recourse for cities like Mobile, which experienced a number of outbreaks of yellow fever in the nineteenth century. Though the bill failed in the Senate, it established a basis for future laws. In 1874, Bromberg sought reelection but lost in the primary to freedman Jeremiah Haralson, who challenged the election and won the seat. Bromberg then returned to Mobile to resume practicing law.

Bromberg was admitted to the state bar in 1876 or 1877, according to differing sources, and was certified to practice in front of the Alabama Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court in 1880. In addition to his law practice, Bromberg was appointed Alabama's Republican commissioner to the World's Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893. He was also vice president of the Southern Conference of Unitarian Churches. Bromberg maintained an interest in infrastructure improvement; in 1901, in connection with casework, he advocated for a re-survey of the Coosa River in the interest of determining navigability on the river and the possibility of industrial development but was unsuccessful. That same year, as the 1901 Constitutional Convention was meeting, he appealed to convention president John B. Knox to prohibit Black citizens from holding elective office, because he feared that denying them suffrage in the new constitution could be challenged in court on the basis of the right to vote granted by the Fifteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. He made similar arguments to state lawmakers in later years, based on his view that voting is a "civil" right, whereas holding office is a "political" right.

A man of many interests, Bromberg wrote short histories on a variety of topics, including Reconstruction in Alabama for the Iberville Historical Society. In it, he seems to disagree with the popular view in Alabama that "carpetbaggers" and Black office holders corruptly ruled the state in that era. He also edited and contributed to the Unionist, a progressive Republican publication in Mobile. In 1925, he revisited his call for a prohibition on Black officeholders in the Alabama Law Review, a response to white fears of racial strife derived from the growing number of Black voters after the Civil War. He also expressed the view that white fears of the Black vote could be lessened by a good public education system for all.

Bromberg died in Mobile on September 4, 1930, at the age of 93, and was interred in Magnolia Cemetery.

Further Reading

- Sizemore, Margaret Davidson. "Frederick G. Bromberg of Mobile: An Illustrious Character, 1837-1928." Alabama Review 29 (April 1976): 104-12.