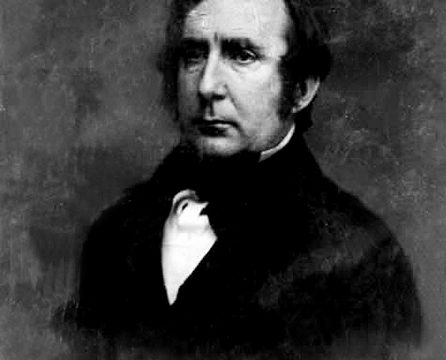

Elisha Wolsey Peck

Elisha Wolsey Peck (1799-1888) was a very successful lawyer, business man, and political figure in nineteenth-century Alabama. He was controversial for opposing secession and for joining with Republicans during Reconstruction as president of Alabama's 1867 Constitutional Convention and as the 12th Chief Justice of the state's Supreme Court from 1868 to 1873.

Peck was born at Blenheim, Schoharie County, New York, on August 7, 1799, to David and Christiana Minturn Peck, the former a farmer and veteran of the Revolutionary War. Peck was educated in the public schools and began reading law in 1819. He was admitted to practice in the state of New York in 1824. That July, Peck decided to settle in what was then called the Old Southwest, so he and a companion drove a horse and buggy to Huntsville, Madison County. After a brief stay, he travelled to Cahaba, Dallas County, then the state capital, but decided to settle in Elyton, Jefferson County, where he soon was regarded as the county's leading lawyer. In 1828, Peck married Lucy Lamb Randall, with whom he would have seven children. Son Samuel Minturn Peck would later become Alabama's first poet laureate.

In 1832, Peck and his family moved to the new state capital, Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, to take advantage of the increased business and political opportunities there. He opened a law practice, prospering personally and professionally from his success in the trial and appellate courts during and after the cotton and land booms of the 1830s. Indeed, he outcompeted hundreds of other young men who journeyed to Alabama to practice law during that period. He initially formed a law partnership with Kentucky native Harvey Ellis, practicing with him until the latter's death in 1842.

Samuel Peck

Peck soon gained a reputation as an expert in arguing cases before the Alabama Supreme Court, a talent that enabled the firm to attract wealthy clients from all over the state. Peck's success continued when he became partners with Massachusetts native Lincoln Clark after Ellis's death and came to be considered among the top-tier lawyers of the period for his detailed and considerable knowledge of the law and its applications. Politically, Peck identified with the Whig Party and its moderate, propertied candidates, but he generally preferred the courtroom to politics. He was appointed to fill an unexpired term as chancery judge, serving from 1839 to 1840 and reportedly ran two unsuccessful campaigns for a circuit judgeship in 1850 and 1856. Despite these political failures, Peck continued to amass wealth; by 1860, his property and financial holdings were worth $100,000, a very large sum for the time. He is also listed in census data as owning 19 enslaved people at this time and likely gained some wealth from the cultivation and sale of cotton. He is notable for successfully defending the family of Milly Walker, a wrongfully enslaved free woman of color.

Samuel Peck

Peck soon gained a reputation as an expert in arguing cases before the Alabama Supreme Court, a talent that enabled the firm to attract wealthy clients from all over the state. Peck's success continued when he became partners with Massachusetts native Lincoln Clark after Ellis's death and came to be considered among the top-tier lawyers of the period for his detailed and considerable knowledge of the law and its applications. Politically, Peck identified with the Whig Party and its moderate, propertied candidates, but he generally preferred the courtroom to politics. He was appointed to fill an unexpired term as chancery judge, serving from 1839 to 1840 and reportedly ran two unsuccessful campaigns for a circuit judgeship in 1850 and 1856. Despite these political failures, Peck continued to amass wealth; by 1860, his property and financial holdings were worth $100,000, a very large sum for the time. He is also listed in census data as owning 19 enslaved people at this time and likely gained some wealth from the cultivation and sale of cotton. He is notable for successfully defending the family of Milly Walker, a wrongfully enslaved free woman of color.

Following Abraham Lincoln's divisive election to the presidency, Peck stood firmly against secession and believed that many white voters shared his opposition. He knew that his sentiments placed him at odds with the pro-Confederates in Alabama. He did not renounce his loyalty to the Union and thus faced threats against his life for it, even being warned to leave Tuscaloosa. He chose to remain and later stated that he believed pro-Confederate friends protected him from harm and financial ruin. He spent the Civil War years largely removed from news and many contacts but continued to represent clients, even filing a few briefs with the state Supreme Court.

After the war, Peck travelled to New York in the summer of 1865, fell ill, and remained there until early November. Having been identified with the Alabama Republican Party as one of its native white leaders, known popularly by pro-Confederates as "scalawags," he was chosen in absentia as a delegate to the Alabama constitutional convention, called to meet in September by provisional governor Lewis E. Parsons. His poor health and general reserve kept him from playing a major in role in that provisional Reconstruction government, as did his purchase of property in Illinois. Thus, he did not return home until early 1867. That October, Peck was elected as a delegate from his district, again in absentia, to a second constitutional convention. He returned to Alabama in time for the November 5 opening session of the convention and was unanimously elected its president. He proved to be fair and firm, appointing equal numbers of the chief Republican factions—"scalawags" and northern-born "carpetbaggers"—to committees, although he favored the latter for chairmanships. Likewise, Peck appointed recently emancipated blacks, or freedmen, as delegates to important committees but not as chairmen (18 of the convention's 100 members were freedmen). An active delegate, he would vote some 70 times.

Peck's most pressing concern as president was ensuring that freedmen were granted full suffrage, as required by the provisions of the Reconstruction acts and the still-pending Fourteenth Amendment. But the issue was complicated because the Reconstruction acts required that the new constitution be ratified by a majority of registered voters, and many registered white voters were former Confederates who made up a substantial minority of the 61,000 whites on the rolls in 1867 (compared with more than 104,000 registered African Americans). Additionally, Radical Reconstructionists pushed for disfranchising white voters who had supported secession, and scalawags opposed the Republican majority's inclusion of a registration oath in the legislative language that would require whites to renounce any support of secession and accept black suffrage and equality.

On November 5, at the height of these conflicts, Peck addressed the convention in a speech in which he supported the proposed oath and the disfranchisement of non-voters while also, in a somewhat conciliatory tone, expressing the desire to establish goodwill with ex-Confederates. In printed versions of the speech, however, Peck stated that the convention should strive to keep Alabama free from the control of "disloyal men." Peck and a majority of "Radical" Republicans feared that in post-Civil War politics, winners would shut losers completely out of the political process. And their Democratic opponents assumed the same, as well. They despised the 1868 Constitution, which was approved in February by an overwhelming majority of votes but not a majority of registered voters, as required by the U.S. Congress. In June, Congress restored Alabama to statehood, despite this failure in the voting process. Democratic delegates would refer to the 1868 document as the "Constitution (So Called) of the State of Alabama" for nearly a decade. Prior to adjournment, the convention nominated a Republican ticket for statewide offices. Peck was nominated for justice of the state Supreme Court in what would be the first time that office was subject to popular vote.

Peck spent little time politicking on his own behalf, but the Tuscaloosa paper Independent Monitor accused him of being a traitor and a hypocrite for opposing slavery while owning slaves. Even Peck's swearing-in ceremony was tarnished when outgoing Chief Justice Abram J. Walker refused to give him the oath of office. Eventually Peck and his colleagues, Thomas M. Peters and Benjamin Saffold, were sworn in on July 14, 1868, by circuit judge William J. Haralson.

Peck's term began in January 1869, and he would be the first federally approved chief justice of the post-Confederate era. Many notable figures in Alabama politics had business with the court during his tenure, including: former Confederate governor Thomas H. Watts; antebellum chief justice Samuel F. Rice; future U.S. senator John Tyler Morgan; future U.S. representative and "Bourbon" governor William C. Oates; and Peck's court reporter Thomas Goode Jones, a Confederate hero and future governor and federal circuit judge.

During Peck's tenure, the court rebounded from its lack of productivity during the war, deciding hundreds of cases between 1869 and 1873, when Peck resigned his post. Of the three justices, Peck typically wrote the fewest decisions per term, leaving the bulk of the decisions to Saffold and Peters. Yet Peck, as chief justice, often reserved some of the most important opinions for himself, including decisions on such important issues as the legal status of Confederate debts and the validity of rulings made by Confederate and provisional Reconstruction courts. In addition, one of his opinions overturned two ordinances passed by the 1867 constitutional convention. Another important ruling, Burns v. State in 1872 (though written by Saffold), abolished criminal penalties for miscegenation, the intermarriage of African Americans and whites.

Peck resigned from the court in March 1873 as his health deteriorated. He returned to Tuscaloosa and lived there until his death on February 13, 1888. He was buried in the city's Greenwood Cemetery.

Further Reading

- Elisha Wolsey Peck Papers, Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

- Freyer, Tony A., Paul M. Pruitt, Jr., et al. Alabama's Supreme Court and Legal Institutions: A History. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: n.p., 1999).

- Kitchens, Joel. "E.W. Peck: Alabama's First Scalawag Chief Justice." Alabama Review 54 (January 2001): 3-32.

- Pruitt, Paul M., Jr. "Scalawag Dreams: Elisha Wolsey Peck's Career, and Two of His Speeches, 1867-1869." Alabama Review 66 (July 2013): 211-39.

- Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk. The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865-1881. Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 1991.

- Fleming, Walter L. Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama. Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Company, 1978.