State Capital at Tuscaloosa

Before Montgomery became the seat of Alabama’s government, Tuscaloosa served as the state capital from 1826 to 1846. The city earned this designation after the Alabama State Senate voted, in a narrow victory for the young city, to relocate the capital from Cahaba (also spelled Cahawba) to Tuscaloosa in 1825. During its reign as capital, Alabama’s government oversaw the creation of the University of Alabama and, more notably, faced a variety of challenges, including the ending of the State Bank of Alabama’s charter as a result of corruption as well as the ongoing conflict with the Creeks and the national economic crisis known as the Panic of 1837. The copper-domed capitol building was completed in 1829 and burned to the ground in 1923.

The new capitol building took time to plan and build, but the work of Alabama’s officials began immediately. After the legislature moved to Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, legislators met in various locations in the city, with its first meeting at Bell Tavern on November 20, 1826. This location was eventually replaced with another on Broad Street, where meetings continued until 1829. During this time, however, legislators passed a resolution to find a permanent location for the legislature. This process took many votes, but eventually lawmakers decided on Childress Hill, named for one of its original owners, Maj. James Childress. The site naturally lent itself to a prominent building because of its central location in the city as well as its elevation overlooking the Black Warrior River. The vote to construct an official statehouse came soon after, on January 3, 1827.

Settling on the design of a new capitol building proved challenging. Early design plans were repeatedly rejected by the selection committee and other lawmakers for a variety of reasons. Some objected to its appearance, and others objected to every design because they saw no reason to relocate from Cahaba. The committee pushed forward in search of an architect whose design could gain majority support. Finally, in February 1827, the selection committee commissioned English architect William Nichols to submit plans for the new building. His portfolio already included other capitol buildings, including the impressive remodel of North Carolina’s capitol building in Raleigh. After a series of revisions and adjustments, the General Assembly approved Nichols’s building plans on December 20, 1827.

The capitol building would take nearly two years to construct and cost far more than the originally allocated $40,000 and an additional $15,000 to enlarge the building. Estimates of the final cost vary between $100,000 and $150,000. The building, a blend of Greek Revival and Federal architectural styles, featured a copper dome over the rotunda visible to passersby on the Black Warrior River, with the two-story entrance hall flanked by Doric columns and facing Broad Street. This dome was the central point where the three wings of the building met. The Senate and House sat in the North and South wings, respectively, whereas the Supreme Court was housed on the ground floor of the smaller western wing. The two wings housing the legislature were symmetrical on either side of the entrance hall and were faced with Alabama-sourced materials, including rusticated, or rough-faced, freestone from Tuscaloosa on the first floor and bricks from Northport on the second and third floors. Other notable architecture features included multi-story Ionic columns at the main entrance, rounded window arches, and a decorative portico over the building’s main entrance.

Records indicate that a large numbers of local craftsmen and contractors were needed to build the impressive structure, but aside from a few named men, most of those who contributed are unknown today. Some of the contractors hired for the work are known to have brought their skilled enslaved laborers, including George Hamer, for certain projects, whereas other Tuscaloosa residents sent their enslaved people to learn skills through forced apprenticeships. The various trades enslaved labor is known to have been used for include preparing logs, joinery, and general carpentry, but others examples are also likely. A number of free Blacks also completed paid labor on the capitol, including Solomon Perteet, Ned Berry, and James Abbott, who all contributed their individual expertise to the capitol’s construction.

The first official meeting of the General Assembly took place in the new capitol during the 1829-30 convening of the government. Eight governors would preside over the state from Tuscaloosa. Of note, John Murphy (1825-29), elected before the building’s completion, was the first. Gabriel Moore (1829-31) gave the first official address in the new capitol building. Joshua Martin (1845-47) was the last, when the capital again moved.

The relocation of the capital to Tuscaloosa brought many years of growth and prosperity, attracting legislators’ families and lobbyists along with hotels, gambling houses, saloons, and other businesses. After 20 years, however, the capital was relocated to Montgomery, Montgomery County, because of its more central location in the increasingly widely settled state. Tuscaloosa, like Cahaba before it, lost a significant portion of its population and much of the financial backing that kept it growing and adapting after the capital was moved. The capitol building was granted to the University of Alabama, which rarely made use of the building and leased it in 1857 to the Baptist Convention of Alabama for the recently established Alabama Central Female College. It operated in the building until it burned down on August 22, 1923.

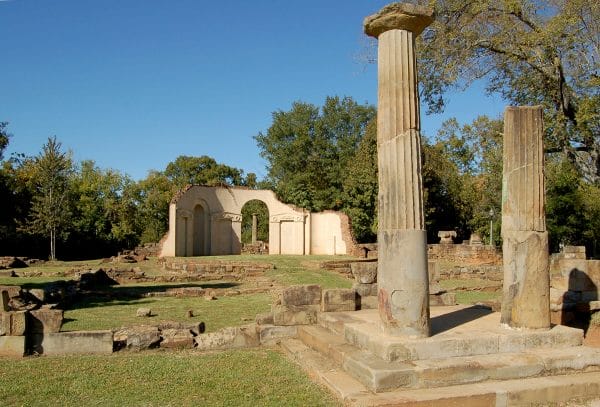

Parts of the building, including bricks and stonework, were taken from the site by residents and used in various projects throughout the city. Little remains today except for an interior wall of the once-grand rotunda as well as the foundation’s perimeter, which shows the building’s size. The ruins are preserved as part of Tuscaloosa’s Capitol Park.

Further Reading

- Clinton, Matthew William. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Its Early Days, 1816-1865. Tuscaloosa, AL: Zonta Club, 1958.

- Hubbs, G. Ward, Tuscaloosa: 200 Years in the Making. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2019.

- Lewis, Herbert James. Lost Capitals of Alabama. Charleston: The History Press, 2014.